The primary objective of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) is to ensure the delivery of comprehensive, high-quality care that improves survival while maintaining quality of life for patients with cancer. This article examines the initiatives of the CoC toward achieving this goal, utilizing data from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) to monitor treatment patterns and outcomes, to develop quality measures, and to benchmark hospital performance. The article also highlights how these initiatives align with the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations for improving the quality of cancer care and briefly explores future projects of the CoC and NCDB.

- •

Cancer is an important part of any discussion about quality because of the complexity of treatment and disproportionate cost of caring for these patients.

- •

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) plays a central role in the Commission on Cancer’s (CoC’s) efforts to ensure the delivery of high-quality cancer care.

- •

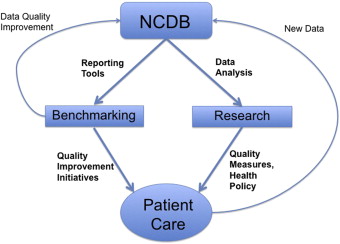

NCDB data affect patient care through two major pathways: hospital benchmarking with resultant quality improvement initiatives and research to develop new quality measures.

- •

The Rapid Quality Reporting System is a novel online NCDB tool that changes the cancer data paradigm by assessing compliance with treatment standards in real time.

- •

Increasing patient-centered care and incorporating patient-reported outcomes represent key next steps by the CoC and NCDB to enhance cancer care.

In its follow-up report in 2000, the IOM advocated for the enhancement of cancer care data systems through several mechanisms as one of the essential steps toward ensuring quality cancer care. These mechanisms included (paraphrased from Part 1 of the recommendations):

- •

Identification and inclusion of a core set of evidence-based quality measures

- •

Standardization of reporting, especially with regard to disease stage and patient comorbidity

- •

Linkage to other data sources (such as administrative data) and special studies to give a more rounded picture of the continuum of cancer care as well as provide the necessary data elements for case-mix adjustment in studies comparing care in one setting versus another

- •

Reporting quality benchmarks and performance data to institutions giving care to patients with cancer

- •

Information technology solutions to increase coverage, quality, and timely availability of relevant clinical data

- •

Training of health service researchers with special emphasis on implementation of quality improvement initiatives and measurement of quality of care.

This report also cited the Commission on Cancer’s (CoC’s) National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) as one of the most promising cancer data systems for affecting quality.

With this backdrop and the understanding that the core mission of the CoC and NCDB is improving the quality of cancer care, the remainder of this article proceeds as follows. First, it describes the structure and organization of the NCDB and examines where the NCDB fits within the larger picture of central cancer registries. Next, it addresses the several mechanisms for enhancing cancer care data systems put forth by the IOM and highlights the ways in which the CoC and NCDB have answered the call either via completed projects or works in progress. In each case, stumbling blocks during implementation and/or limitations will be noted. Finally, it provides a sense of the direction and vision of the CoC and NCDB for impacting and improving cancer care going forward.

NCDB-cancer registry structure and organization

The NCDB is a joint program of the American College of Surgeons’ CoC and the American Cancer Society and is one of three main cancer registry systems in the country. The other two programs are the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The NPCR receives information on new cancer cases from virtually every state through the system of state cancer registries. This system capitalizes on the fact that cancer is a reportable disease and, therefore, captures an estimated 96% of the United States population. In comparison, SEER collects data from regions in 15 states using complex sampling methods and represents about 28% of the population. In contrast to the NPCR and SEER programs, which are both population-based, the NCDB is a hospital-based registry that includes cases from approximately 1500 CoC-accredited institutions nationwide and currently accounts for approximately 70% of cancers diagnosed in the United States.

Although the NCDB is hospital-based, because of its fairly large footprint NCDB data can be reasonably extrapolated to the population for many tumor sites, with a few important caveats. Compared to non–CoC-approved hospitals in the United States, CoC hospitals are more likely to be teaching or research hospitals. Although three-quarters of hospitals participating in the CoC accreditation program are community-based centers and account for approximately 60% of the cases reported to the NCDB, teaching or research centers make up a fifth of all CoC-accredited programs and more than a third of the cases reported to the NCDB on an annual basis ( Table 1 ). This has possible implications for the generalizability of NCDB data. In addition, tumors that are much less likely to require hospitalization for treatment (eg, early-stage melanoma and prostate cancer) are proportionally underrepresented in the NCDB. Furthermore, there can be significant differences by region due to variable penetrance of CoC accreditation. In 2006, the distribution of CoC-approved institutions by state ranged from 0% in Wyoming to 100% in Delaware. A comparison of NCDB and state registry data between 2003 and 2007 for 28 states demonstrated that the proportion of all cancer cases captured in the NCDB was as low as 27.2% in Arizona to as high as 90.0% in North Dakota (Anthony S. Robbins, MD, PhD, American Cancer Society, personal communication, 2012).

| Cancer Program Type | As a % of CoC-Accredited Programs | As a % of Cases Reported to NCDB |

|---|---|---|

| Small community | 33 | 14 |

| Comprehensive community | 42 | 48 |

| Academic | 17 | 26 |

| NCI-designated | 2 | 9 |

| Veterans Affairs (VA) | 4 | 3 |

| — | n = 1500 | n ≈ 1.1 million |

The NCDB processes data on over one million cancer cases annually and contains information on almost 28 million cases in total since 1985. Registrars report specific data elements that include patient demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, payer information), cancer stage (clinical and pathologic), tumor characteristics (including histology, grade, site-specific prognostic factors), first-course therapy (type of surgery, type and extent of radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and hormone therapy), and outcomes (surgical margin status, recurrence, and survival). Several of these data items are common across all three registry systems, but a few are unique to NCDB data—notably International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) codes for comorbid diagnoses and detailed radiation modality and dosing information. Data are collected in accordance with nationally standardized procedures and reporting formats coordinated by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR), the collaborative umbrella organization for all central cancer registries in the United States and Canada. Data reported to the NCDB are then linked to tertiary data sources (facility and census data) to provide hospital characteristics and area-based socioeconomic indicators, such as income and education. These data are processed and fed back to the reporting hospitals so they can assess the performance of their cancer program either on its own or compared to other programs. This is achieved through a variety of online tools (see later discussion).

Monitoring and Improving Cancer Care Through Enhanced Data Systems

Before delving into each of the mechanisms proposed by the IOM and the response of the CoC and NCDB, it is useful to have a conceptual framework for how the CoC seeks to affect quality-of-care using cancer registry data. For simplicity, NCDB data may be viewed as affecting patient care through two major pathways: (1) benchmarking and the resultant quality improvement initiatives with respect to established standards and (2) research to develop new quality metrics ( Fig. 1 ).

Evidence-based cancer care quality measures

The classic paradigm for assessing health care was defined by Donabedian and divides quality measures into three main types: structure, process, and outcome. Structure refers to the attributes of the system in which care is delivered (eg, the number of hospital beds or the presence of an electronic health record). Process measures encompass the interactions between the providers and patients in the actual delivery of health care. An example might be whether an eligible patient received appropriate chemotherapy for their cancer. Outcomes are those changes in health status that are attributable to the health care received, such as mortality or rates of surgical-site infections.

An alternative approach, which perhaps has a more administrative and/or surveillance focus, classifies quality measures based on their potential utilization. With this approach, measures are divided into (1) accountability measures, which are supported by data from randomized controlled trials and can be used for public reporting and payment incentive programs; (2) quality improvement measures, supported by evidence from retrospective studies and used for internal monitoring of performance; and (3) surveillance measures, supported by consensus expert opinion and used to monitor patterns of care and guide policymaking. This framework is the one used by the National Quality Forum (NQF) and therefore provides the terminology adopted by the CoC in its process of measure development.

The CoC screens and evaluates potential measures using the four domains used by the NQF :

- 1.

Importance . Measures are accompanied by a full literature review of trials or relevant meta-analyses, with a corresponding evaluation of how the measure relates to outcomes and clinical practice guidelines. This also provides the rationale for whether the measure should be described as an accountability, quality improvement, or surveillance measure. Each measure includes an estimate of the number of cancer cases potentially affected and describes any anticipated sensitivity or variance issues associated with the measure.

- 2.

Scientific acceptability . Measures are well defined, precisely specified, and adaptable to patient preferences. They can be regularly applied with consistent results that adequately discriminate between real differences in provider behavior. When a risk-adjustment strategy is necessary, this is also described.

- 3.

Usability . Measures can be used for assessing programmatic performance, making decisions, and implementing change.

- 4.

Feasibility . The relative ease or burden of data collection is considered. Data collection should be clearly associated with the delivery of care and obtained within the normal flow of clinical care.

The NCDB’s reliance on data reported from hospital cancer registries is the central limiting factor shaping these particular discussions. For example, measures cannot be defined around administration of a particular therapeutic drug at this time because specific drugs are not identified in the registry. Confidentiality and audit requirements are also important considerations.

In 2005, as part of the response to the IOM report, the NQF initiated a call for evidence-based cancer quality measures. In a joint effort with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the CoC developed six measures for breast and colorectal cancer care. Five of these measures were endorsed by the NQF in 2007 ( Table 2 ). These quality measures have all been widely adopted and compliance rates are now actively monitored in cancer programs across the country.