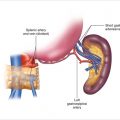

Figure 9.1

Levels of the central (a) and lateral (b) neck

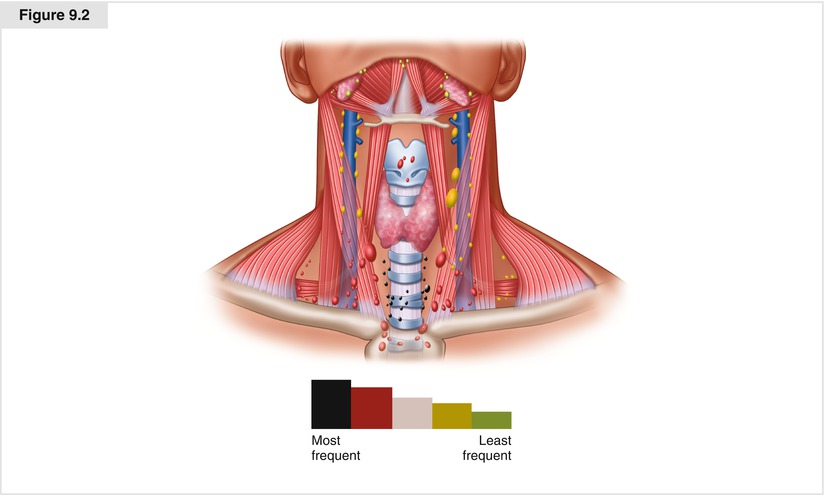

Figure 9.2

Rates of metastasis are highest to levels IIa to Vb, with disease less common at levels I, IIb, and Va

9.2 Modified Neck Dissection for Lateral Cervical Lymphadenectomy

9.2.1 Incision Planning

When considering an incision, the surgeon must ensure that adequate access will be available to all levels of the neck planned for excision. Previous incisions, as well as the potential need for further surgery on the ipsilateral lateral, central, and contralateral neck, also should be considered in planning the incision.

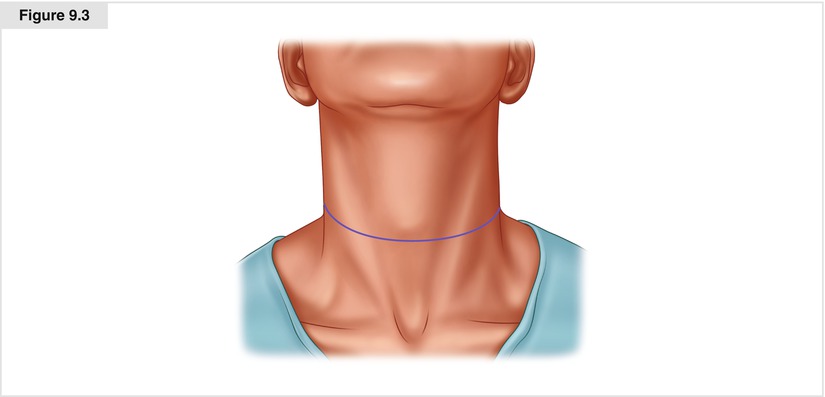

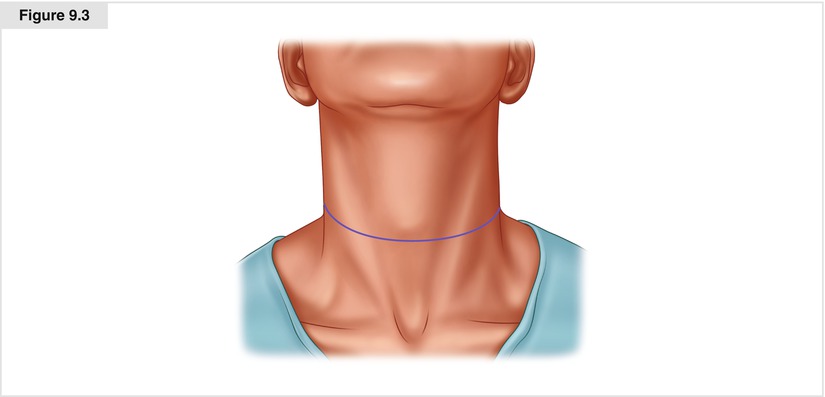

Traditional J-shaped incisions, which ran from the mastoid process, curving down into the neck and joining the thyroidectomy incision, crossed the lines of relaxed skin tension and therefore resulted in poor cosmetic outcomes. Instead of that incision, we recommend a single transverse incision at about the level of the cricoid cartilage, extended on either side as necessary to provide all the necessary exposure for thyroidectomy and appropriate regional node dissection as needed (Fig. 9.3). A well-placed incision, usually in a skin crease slightly above the level of the cricoid cartilage, can be extended to both sides of the neck, affording access to all levels of the neck and leading to optimal cosmetic outcome without compromising surgical access [4]. If there is a scar from a previous thyroidectomy incision, then every attempt should be made to incorporate that scar in the neck dissection incision, if possible. Doing so will avoid multiple scars and minimize potential vascular compromise of the skin island between old and new incisions.

When performing a neck dissection from levels IIa to Vb, the incision should extend to the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and far enough across the midline to allow retraction to expose the accessory nerve in level II.

For access to perform unilateral or bilateral comprehensive modified neck dissections of levels I through V, this incision can be extended from the anterior border of the ipsilateral trapezius muscle to the contralateral trapezius if required to encompass levels Va, IIb, and I.

Figure 9.3

A single transverse incision at about the level of the cricoid cartilage, extended on either side as necessary, can provide all the necessary exposure for thyroidectomy and appropriate regional node dissection with optimal cosmetic outcome

9.2.2 Raising Skin Flaps

The skin incision is made using a scalpel, and the platysmal layer is identified deep to the superficial fat. Subsequent dissection proceeds with the use of electrocautery, set at an appropriate level to maximize hemostasis and minimize charring of tissue. The platysma is incised throughout the length of the incision. At the lateral margins of the incision, and in the midline region, the platysma is flimsy or absent. By dissecting on a broad front, with adequate retraction of the skin edge using sharp hooks, the surgeon can easily identify a subcutaneous plane corresponding to the undersurface of the platysma, which allows the flaps to be elevated with minimal blood loss.

Particular attention should be paid to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve during elevation of the upper flap. This structure lies deep to platysma, but superficial to the fascial capsule of the submandibular gland. As the upper skin flap is elevated, the contour of the lower border of the submandibular salivary gland can be identified just cephalad to the digastric muscle. At this point, if level I is not to be dissected, then no further superomedial elevation of the flap is required, and the inferior surface of the submandibular gland can be mobilized superiorly to expose the digastric muscle, marking the superomedial limit of dissection. This landmark is vital to the procedure and should be dissected free from the hyoid to the mastoid process. To expose the digastric muscle completely, the common facial vein and other venous tributaries crossing the digastric muscle from the superficial surface of the submandibular gland should be divided and ligated. If level I is to be included, however, dissection proceeds under the glandular fascia, which is then elevated off the gland in a superior direction, with the marginal mandibular nerve contained within the fascial tissue superficial to the gland. This dissection is continued up over the mandible, thereby dissecting, shifting, and retracting the nerve out of the field of dissection to safety. The upper skin flap should be carefully elevated over the surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, so as to protect and preserve the greater auricular nerve and to minimize skin anesthesia/paresthesia following surgery.

The inferior skin flap should be elevated in a similar fashion down to the level of the clavicle. Because all nodal dissection is done in a plane deep to the sternomastoid muscle, it is not necessary to raise the skin flaps over the posterior triangle lateral to the posterior border of the sternomastoid muscle. Avoiding this step during elevation of the flaps protects the accessory nerve in the posterior triangle, preventing any inadvertent injury to it. Elevation of the skin flap over the posterior triangle is required only if there are grossly enlarged metastatic nodes in the posterior triangle of the neck. In that setting, extreme care must be exercised to find the accessory nerve at Erb’s point, where it exits from the sternomastoid muscle and runs inferolaterally to enter the trapezius muscle. The cranial branch of the accessory nerve is joined by a spinal contribution from the cervical plexus at the root of C2, and care should be taken to preserve both branches in an attempt to minimize shoulder dysfunction. If level V is to be formally dissected, exposure of the trapezius muscle superiorly allows dissection to proceed on its lateral aspect. The accessory nerve enters the muscle on its medial surface, so using this technique protects the nerve.

9.2.3 Selective Neck Dissection of Levels IIa, III, IV, and Vb

At this stage, the borders of the dissection field are exposed. The deep cervical fascia at the anterior border of the sternomastoid muscle is divided, and dissection proceeds along the medial aspect of the muscle, to allow its retraction laterally. Small blood vessels entering the muscle are divided and ligated. These can be expeditiously controlled with the use of either electrocautery or hemostatic devices such as LigaSure™ (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) or harmonic scalpel. The plane is followed posteromedially until the roots of the cervical plexus are identified. These structures mark the level of the base of the dissection. Several hemostats are then applied to the nodal tissue in the deep jugular chain, allowing its traction medially and thus permitting retraction of the specimen medially to facilitate dissection of lymph nodes lateral to the internal jugular vein and overlying the roots of the cervical plexus. Deep right-angled retractors or small Richardson retractors are used to retract the sternomastoid muscle laterally. With adequate retraction, a plane between the floor of the posterior triangle and the specimen is defined from the level of the accessory nerve superolaterally to the level of the clavicle inferiorly.

Having identified the superficial, deep, posterior, and superior borders of the dissection, the specimen is now dissected in a lateral-to-medial and either superior-to-inferior or inferior-to-superior direction, depending on the extent and level of gross disease. Usually, the most significant disease is addressed as the final part of the dissection, in order to maximize access to the most challenging part of the dissection. It is generally preferable to dissect from the superior aspect in an inferior direction, following the accessory nerve as it passes under the digastric to run lateral to the internal jugular vein. Retraction of the digastric muscle exposes the carotid sheath, and careful dissection allows identification of the internal jugular vein. Small venous tributaries overlying the surface of the internal jugular vein must be divided and electrocoagulated or ligated. In some patients, the occipital artery crosses the internal jugular vein on its surface and requires division and ligation. This landmark is crucial, and great care must be taken not to injure the great vessels as they pass into the skull base.

The fascia of the vein is dissected to identify a clean plane separating the vein from the specimen, which is mobilized, forming the superior corner of the dissection. Meticulous attention is paid to clearing the jugulodigastric lymph nodes at level IIa. Doing so will expose the accessory nerve laterally. Dissection of level IIb is not necessary unless gross metastatic lymph nodes are present at level IIa. The specimen can gently be dissected free of the internal jugular vein in an inferior direction. Dissection proceeds down the length of the jugular vein, remaining superficial to the branches of the cervical plexus and the prevertebral fascia, in order to protect the phrenic nerve. The full length of the carotid sheath will gradually be exposed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree