Historically the surgical management of extremity soft-tissue sarcomas (ESTS) commonly involved amputation. Nowadays limb-sparing, function-preserving surgery is the standard of care for ESTS. Adjuvant therapies such as radiation therapy and chemotherapy are used selectively in an effort to minimize both local recurrence and distant spread. Less common modalities, such as isolated limb perfusion, isolated limb infusion, and hyperthermia are being evaluated to potentially expand the cohort of individuals who may be eligible for limb-sparing surgery and to improve outcomes. This article reviews the standard and evolving approaches to the management of ESTS.

Approximately 50% of sarcomas arise in the extremities, with a threefold higher rate observed in the lower extremities than in the upper extremities. Historically the surgical management of extremity soft-tissue sarcomas (ESTS) commonly involved amputation. However, radical surgery was not necessarily curative. In an early series of 297 patients with lower extremity ESTS from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 47% underwent amputation. While local recurrence rates were higher in patients undergoing en bloc wide soft-tissue resection, the 5- and 10-year overall survival (OS) rates were 63% and 50% after limb-sparing surgery and 45% and 29% after amputation. Such results led investigators to seek to improve local control with less morbid surgery.

Limb-sparing, function-preserving surgery is now the standard of care for ESTS. Adjuvant therapies such as radiation therapy (RT) and chemotherapy are used selectively in an effort to minimize both local recurrence and distant spread. Less common modalities, such as isolated limb perfusion (ILP), isolated limb infusion (ILI), and hyperthermia are being evaluated to potentially expand the cohort of individuals who may be eligible for limb-sparing surgery and to improve outcomes. This article reviews the standard and evolving approaches to the management of ESTS.

Risk factors for recurrence and death

In a large contemporary retrospective review of 997 ESTS from Istituto Nazionale Tumori in Milan, Italy, margin status, size, grade, depth, and histologic subtype were independent predictors of mortality. The 5- and 10-year mortality estimates were 16% and 19% for patients with macroscopically complete resections with negative microscopic margins (R0 resection), and 29% and 38% for patients with macroscopically complete resections with positive (<1 mm) microscopic margins (R1 resection) ( P = .0003). Among the R0 patients, cause of death was distant metastases in 100% whereas among R1 patients, 17% died of locoregional progression without distant metastases. Among the subset of patients with R1 resections, the 5- and 10-year mortality rates were 21% and 21% for those with a biological margin (such as intact fascia) compared with 30% and 40% for those with tumor directly at the inked margin ( P = .36). Additional risk factors negatively affecting local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS), and disease-specific survival (DSS) included patient age older than 50 years, recurrent sarcoma, and proximal location.

Individuals diagnosed with or suspected of having ESTS should be referred to centers specializing in the management of such tumors. Treatment at such centers improves both limb salvage and survival rates.

Limb-salvage surgery

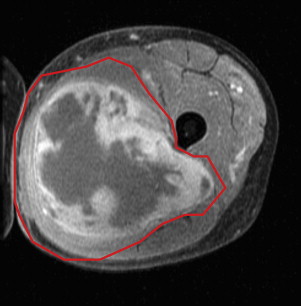

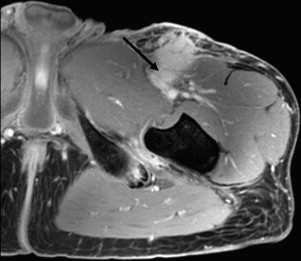

The definitive therapy for ESTS, as for all localized sarcomas, is a radical, margin-negative resection ( Fig. 1 ). No adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy can substitute for an inadequate operation. When margins are believed to be either microscopically positive (R1 resection) or macroscopically positive (R2 resection), one must strongly consider whether another operation is warranted to achieve sufficient margins. What constitutes an adequate margin still remains a matter of debate, dependent in part on histology and tumor location. In general, a 1- to 2-cm margin of normal, nonneoplastic tissue should be the goal of any operation. However, a close margin in the setting of an intact fascial plane is usually acceptable. When such a margin cannot be achieved because of proximity or involvement of critical neurovascular structures, RT, ILP/ILI, and resection of vascular and/or neural structures with reconstruction should be considered ( Fig. 2 ).

As discussed herein, RT is commonly used to reduce the risk of local recurrence while sparing the limb and functionality even after a margin-negative resection. However, limb-sparing, function-preserving therapy does not always require RT. Patients with small, low-grade tumors resected completely or certain small, superficial high-grade tumors resected with wide margins may be treated with surgery alone. Furthermore, patients with certain histologic subtypes of ESTS, such as atypical lipomatous tumors, which have a low risk of local recurrence and distant spread, may be treated with surgery alone despite close margins.

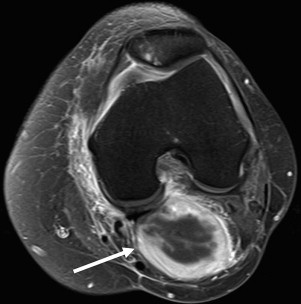

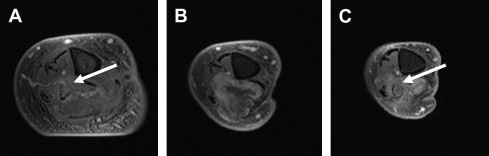

In patients with metastatic disease, surgery for the primary or a locally recurrent tumor may still be considered. The goal of surgery changes from curative intent to palliation. Fig. 3 illustrates a patient with an unclassified sarcoma of the left popliteal fossa with regional soft-tissue and lung metastases, who underwent resection of the popliteal lesion for pain control. Fig. 4 shows images of patient with a local recurrence in the right calf causing a fibular fracture and pain, requiring amputation even in the context of lung metastases.

Limb-salvage surgery

The definitive therapy for ESTS, as for all localized sarcomas, is a radical, margin-negative resection ( Fig. 1 ). No adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy can substitute for an inadequate operation. When margins are believed to be either microscopically positive (R1 resection) or macroscopically positive (R2 resection), one must strongly consider whether another operation is warranted to achieve sufficient margins. What constitutes an adequate margin still remains a matter of debate, dependent in part on histology and tumor location. In general, a 1- to 2-cm margin of normal, nonneoplastic tissue should be the goal of any operation. However, a close margin in the setting of an intact fascial plane is usually acceptable. When such a margin cannot be achieved because of proximity or involvement of critical neurovascular structures, RT, ILP/ILI, and resection of vascular and/or neural structures with reconstruction should be considered ( Fig. 2 ).

As discussed herein, RT is commonly used to reduce the risk of local recurrence while sparing the limb and functionality even after a margin-negative resection. However, limb-sparing, function-preserving therapy does not always require RT. Patients with small, low-grade tumors resected completely or certain small, superficial high-grade tumors resected with wide margins may be treated with surgery alone. Furthermore, patients with certain histologic subtypes of ESTS, such as atypical lipomatous tumors, which have a low risk of local recurrence and distant spread, may be treated with surgery alone despite close margins.

In patients with metastatic disease, surgery for the primary or a locally recurrent tumor may still be considered. The goal of surgery changes from curative intent to palliation. Fig. 3 illustrates a patient with an unclassified sarcoma of the left popliteal fossa with regional soft-tissue and lung metastases, who underwent resection of the popliteal lesion for pain control. Fig. 4 shows images of patient with a local recurrence in the right calf causing a fibular fracture and pain, requiring amputation even in the context of lung metastases.

Reconstruction

The ability to save a limb and retain function after resection of a sarcoma may require complex soft-tissue and neurovascular reconstruction. Reconstruction may be performed at the time of the original resection or may be staged after a short interval, particularly if there is concern about the margins. Although a comprehensive review of reconstruction options is beyond the scope of this article, the oncologic surgeon should consider preoperatively the need for reconstruction. Split-thickness skin grafts, full-thickness skin grafts, rotational fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous flaps, pedicled muscle flaps, free flaps, nerve interpositions, and other advanced reconstructions by a plastic surgeon, and vascular grafts by a vascular surgeon, may be necessary.

Radiation therapy

The landmark prospective phase III trial from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) randomizing patients with ESTS to limb-sparing surgery plus external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or amputation established the current standard of care. In this study, 27 patients underwent limb-sparing surgery plus EBRT (5000 rad to the anatomic area and 6000–7000 rad to the tumor bed), and 16 patients underwent amputation. All patients received postoperative chemotherapy. There were 4 local recurrences in the limb-salvage group and none in the amputation group ( P = .06). There were no differences in 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) (71% vs 78%, P = .75) or 5-year OS (83% vs 88%, P = .99). This trial established the new standard of care: radical resection plus EBRT has no worse long-term survival outcomes than amputation, while allowing limb preservation. However, EBRT following a marginal excision should not be considered an adequate substitute for a more radical function-sparing resection achieving wide margins.

Another prospective trial from the NCI randomized patients with ESTS treated with limb-sparing surgery (and for high-grade tumor patients only, postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy) to receive or not receive postoperative EBRT. Among patients with high-grade ESTS, the estimated 10-year actuarial local failure rates were 0% in the EBRT arm and 22% in the no-EBRT arm ( P = .003). There were no differences in distant recurrence or OS rates. Among patients with low-grade tumors (no chemotherapy), local recurrences were noted in 4% who received EBRT and 33% who did not ( P = .016). When patients with desmoid tumors and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans were excluded, the rates of local recurrence were 5% and 32%, respectively ( P = .067).

Based on these data, the authors typically offer EBRT to patients undergoing limb-sparing surgery for large, deep tumors, high-grade tumors, tumors incompletely excised, and tumors lying close to neurovascular structures.

Are there patients in whom EBRT is not necessary? In a study of 74 patients with primary localized truncal and ESTS treated without RT at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the 10-year actuarial local recurrence rate was 7% and the 10-year OS rate was 73%. The only predictor of local recurrence was a histologic margin of less than 1 cm. Of interest, tumor grade was not a predictor of local recurrence. Of importance is that the median tumor size was 4 cm and one-third of the tumors were superficial, potentially reflecting a selection bias for the type of patients not treated with EBRT.

Based on these data, the authors offer the option of no RT for patients with small (<5 cm) tumors for which at least 1-cm margins are possible, particularly if the tumors are superficial, and provided that the patient can reliably be followed and that a local recurrence could still be treated with salvage function-sparing surgery. Although these data did not find a difference in local recurrence based on tumor grade, the authors are cautious about offering no radiation to patients with high grade tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree