Models of care for falls and fracture prevention

The authors of this chapter work at Vancouver General Hospital, a quaternary care center in British Columbia, Canada. As a major medical and surgical center, a large number of patients admitted following a fall require surgical interventions and often a prolonged hospitalization. A decline in functional status often follows this. In 2008, the local Centre for Hip Health, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and the University of British Columbia collaborated to form the Falls Prevention Clinic. This clinic accepted patients referred from acute care and the community who fulfilled their research criteria. All those who did not fulfill research criteria were referred for assessment and treatment in a General Geriatric Medicine Clinic as a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) was accepted as standard care. Patients at the Falls Prevention Clinic initially complete the Physiological Profile Assessment (PPA), which is then combined with a CGA to provide a treatment plan.

A CGA is a tool that has been shown in multiple metaanalyses to better identify, treat and prognosticate outcomes in older adults than standard medical assessment alone. In Struck et al.’s 1993 metaanalysis, a CGA was shown to decrease mortality by 14%–35%, have an odds ratio (OR) of 1.80 of living at home at 6 months, and reduce total readmission rates by 12% . A metaanalysis by Ellis et al. in 2011 showed a CGA increased likelihood in patients being alive and living in their own home with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 17 for mortality benefit and an OR of 0.78 of needing to move to long-term care .

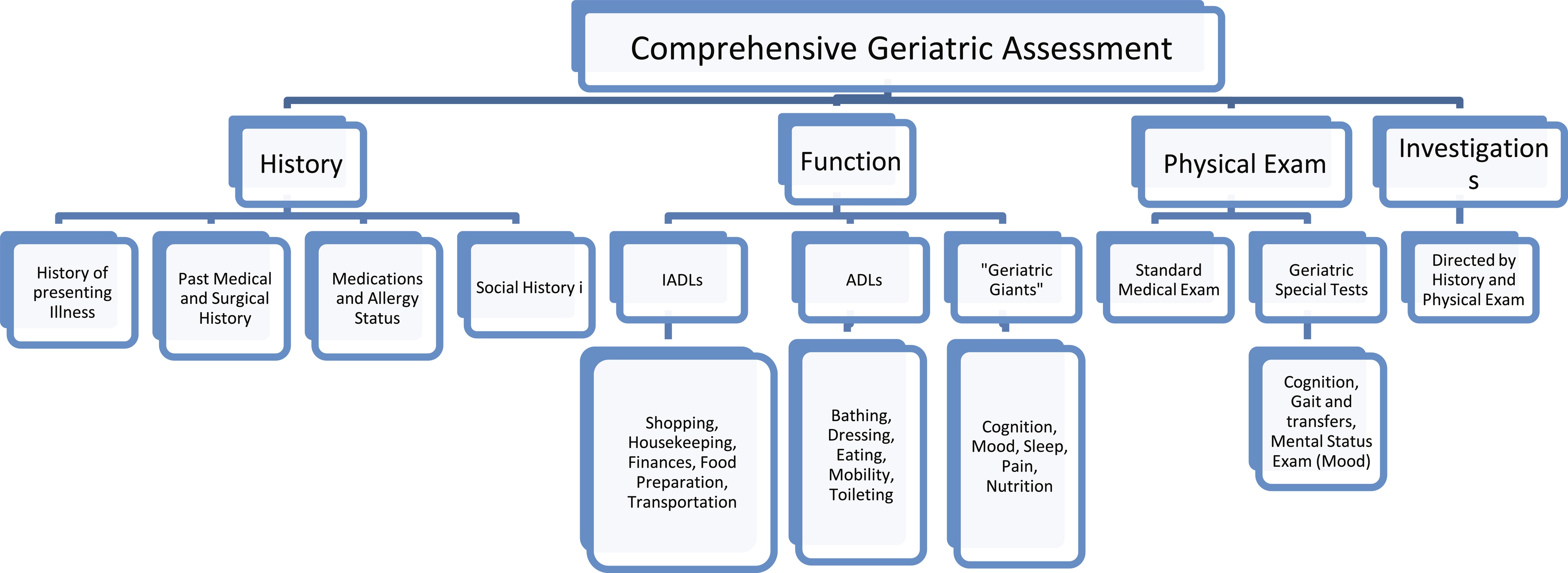

A CGA follows a multidomain model that is implemented in care settings spanning acute, outpatient, and long-term care. The CGA begins with the usual medical assessment domains of history of presenting illness and past medical and surgical history. Additional information recorded includes a functional review of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Independent Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). A Review of Systems of the so-called “Geriatric Giants” including cognition, mobility (including falls), mood and mental health, sleep, pain, nutrition, continence, and polypharmacy is completed as an overlap with a basic functional review. A social history is then obtained with attention to the patient’s support network and their personal history of educational status, work history, smoking, alcohol, and drug use. A review of their current living situation is also completed with questions regarding housing accessibility and knowledge of community supports. A physical examination as per a usual medical exam is then conducted with the addition of special tests for cognition, mobility, and mood. Standard investigations are reviewed, and additional ones are requested based upon a patient’s presenting complaint ( Fig. 1 ).

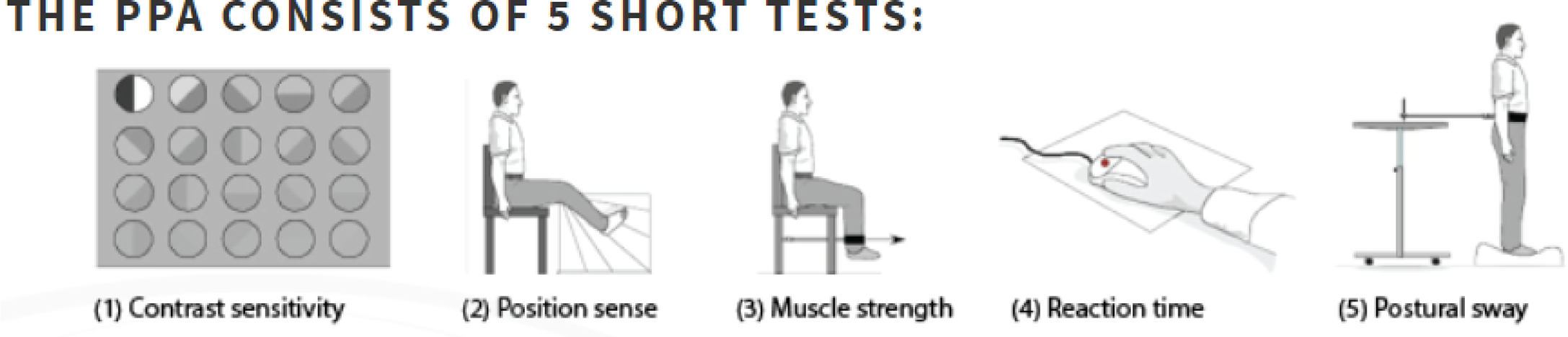

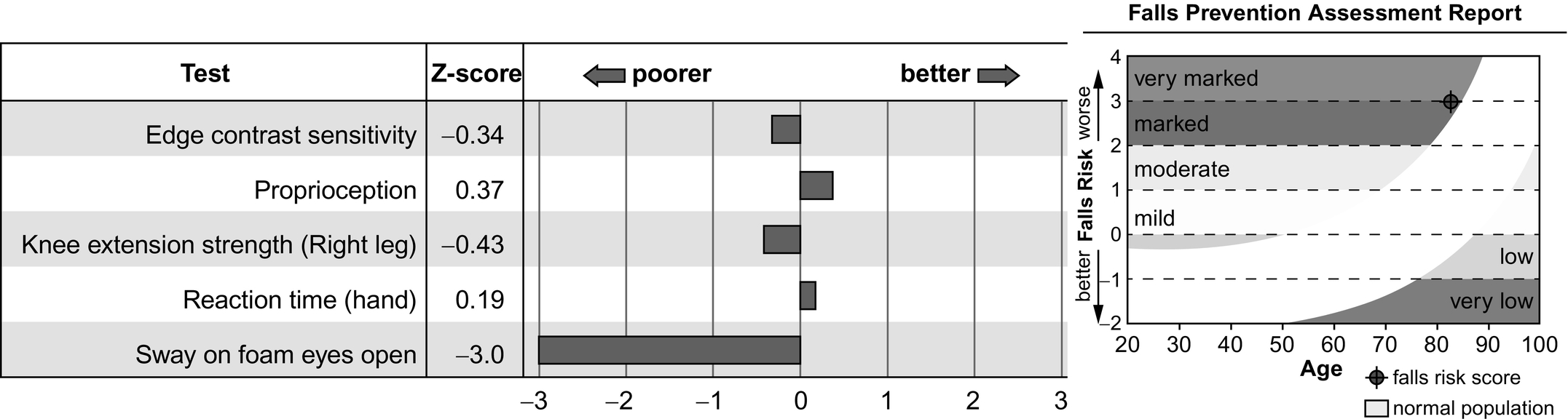

The PPA was developed in 2003 by the Falls and Balance Research Group of the Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute, Sydney, Australia . The PPA consists of five parts: contrast sensitivity, position sense, muscle strength, reaction time, and postural sway. This information is collected and collated versus normative data, and deficits are identified. A printout of the information is created for the patient. Nonphysical risk factors for falls risk, including cognition and mood, are also assessed as the first stage of the Falls Prevention Clinic visit as part of a CGA. The information is then provided to a specialist in Geriatric Medicine (Geriatrician) who completes a CGA along with the PPA and can offer a targeted treatment plan for the patient. Of particular help is the printout of the PPA to illustrate the deficits and the goals for improvement. Patients are then followed in the 6-month interval to complete three visits (0, 6, 12 months). At each visit, the patient undergoes the same testing. The PPA is repeated, and the information is provided in a printout to the patient. The cognitive and mood screens of the CGA are also repeated. With the objective information, physicians and patients are able to track progress ( Figs. 2 and 3 ).

The combined CGA and PPA identified several subtypes of patients concerning the etiology of the falls. The biggest group of our Falls patient population is generally frail with diffuse muscle weakness clinically labeled as sarcopenia. This is clearly seen when using the PPA with the predominance of patients falling below -2SD, and often -3SD, on postural sway. In about 20%–25% of patients, we identify polypharmacy or adverse drug reactions as a primary or major cause of falls. Medications that affect cognition and alertness are particularly important risk factors. Classes include major tranquilizers, neuroleptics, sedative-hypnotics, anticonvulsants, and antidepressants. Antihypertensives causing postural hypotension are also a concern. Medications that have high anticholinergic properties are particularly troublesome. The commonly used polypharmacy tools such as the Beers’ Criteria and STOPP/START are helpful to identify particular culprit medications for a fall risk. Patients with a known neurodegenerative disorder are typically not seen in this clinic as it is felt these patients are best served in a clinic targeted to their movement disorder. However, we have found that falls can often be the first sign of these disease processes and go unrecognized until a CGA and PPA unmask them. Approximately 10%–15% of our Falls Clinic population receive new diagnoses such as Parkinson’s disease or Parkinson’s plus syndrome, cervical myelopathy, or proximal muscle myopathy due to a primary neurological disorder. In about 10% of the population, no single major cause can be identified. In the setting, we have found it helpful to address all the potential risk factors. In doing this, the small incremental benefit that occurs is often sufficient to raise people out of the high-risk zone.

At the inception of the Falls Prevention Clinic, the first research question was “Does a home-based exercise program reduce falls among community-dwelling older adults who present to a fall prevention clinic after a fall?” . This study was carried out from 2009 to 2018. This was a randomized control trial with a primary outcome of self-reported falls. The control arm received standard care from a Geriatrician. The intervention arm received usual care plus visits, and telephone follow-up with a physical therapist providing a strength and balance training exercise program. Both the control and intervention were carried out for 12 months. The absolute difference in fall incidence was 0.74, and there were no adverse events related to the intervention. From this research experience, the authors learned that the usual care of a CGA and treatment plan could be further optimized with a formalized exercise program. This could be through a direct connection with the clinic or a referral to community services offering similar programs.

The Falls Clinic requires more manpower than a standard clinic with support staff to complete the PPA and a Geriatrician to interpret and provide treatment plans. As such, a feasibility and acceptability study was conducted . A 12-month prospective cohort study was conducted. This focused on > 70-year-old community-dwelling adults attending the Falls Prevention Clinic. Clinic attendance was used as an assessment for feasibility. Acceptability was measured by compliance with recommendations, completion of monthly fall reporting calendars, and patient experience. The most common clinical recommendations were referrals to other healthcare workers, medication changes, exercise prescriptions, and lifestyle modifications. Feasibility was demonstrated by 65% attendance. Acceptability was demonstrated with 69% compliance. Referrals to other healthcare professionals and medication changes had a 78% compliance rate. Exercise prescription from the Geriatrician had a 58% compliance and lifestyle modifications 35%. Based upon this outcome, the team at the clinic was encouraged by the positive benefit to patients. It also highlighted that there is more to be done to improve the outcomes for patients and grow the clinic in scope and efficacy.

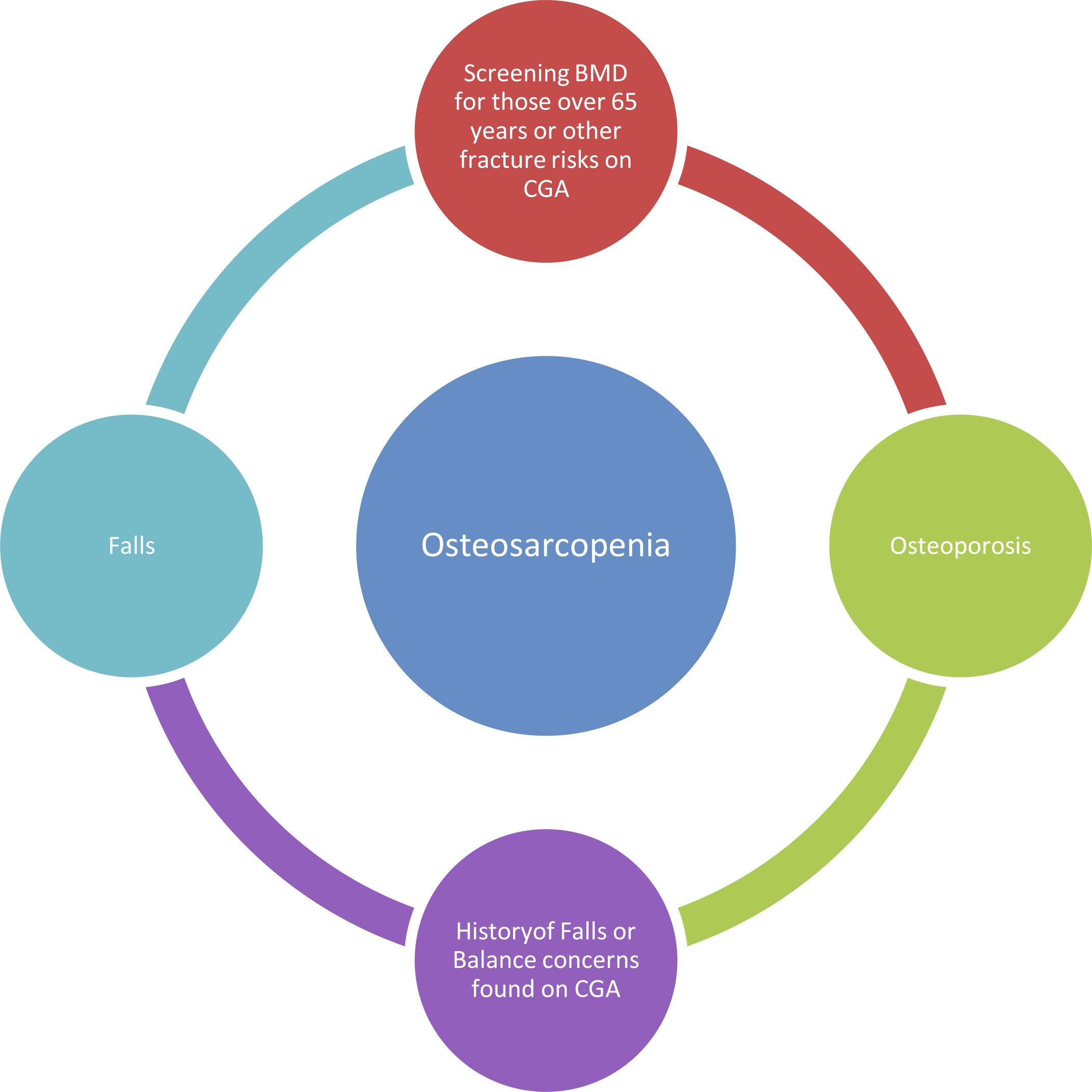

Osteoporosis care in our region was scattered across many different clinics. The largest of these was located at the local Women’s Hospital, but the clinic was closed due to restructuring. Left without a hospital-based program and patients pending follow-up, a new Osteoporosis clinic was created and temporarily housed in the exact location as the Falls Prevention Clinic. Due to the overlap of Geriatricians involved in Falls and Osteoporosis, this worked well. Over time the strong relationship between Osteoporosis and Falls care became apparent. The history and physical exams required by both groups of patients are very similar. Treatment plans for both are parallel. The co-location of these clinics also sparked discussion among the clinicians and researchers involved. Many patients presented with both falls and fractures but those with only falls appeared to carry a higher fracture risk, and those with only fractures were worrisome for their falls risk ( Fig. 4 ).