Miscellaneous Skin Conditions

Daniel P. Krowchuk

KEY WORDS

Alopecia

Dermatitis

Drug eruptions

Fungal infections

Hypersensitivity reactions

Papulosquamous diseases

The identification and management of skin disorders is an important component of adolescent and young adult (AYA) health care. According to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, an ongoing survey of office-based physician practice, in 2010, there were an estimated 47.9 million visits made by persons 13 to 26 years of age to general or family physicians, pediatricians, or internal medicine physicians.1 In 17.8% of visits, a diagnosis of a dermatologic disorder was made.1 This chapter reviews the identification and management of dermatologic diseases that affect AYAs, addressing the conditions most likely to be encountered by clinicians. For additional information, readers should consult a standard dermatology text or atlas. Of note, infestations (scabies and pediculosis) and molluscum contagiosum are discussed in Chapter 62.

The term dermatitis (or eczema) refers to inflammation of the epidermis and superficial dermis. Common forms of dermatitis that affect AYAs include atopic, allergic contact, and seborrheic.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic disease that is likely the result of multiple factors, including genetics, epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and an immune response to Staphylococcus aureus. Among the more than 20% of children who develop AD, most have a resolution of symptoms by adolescence or adulthood.2 However, 10% to 30% do not and a smaller number experience the onset of disease as an adult.2

Clinical Manifestations

In AYAs, AD is characterized by erythematous patches located in flexural areas, such as the antecubital and popliteal fossae. The face (including the eyelids), neck, and hands also may be involved (Fig. 22.1). A variant of hand dermatitis is dyshidrotic eczema in which deep-seated, intensely pruritic vesicles involve the lateral aspects of the digits or palms (e-Fig. 22.1). In persons of color, AD lesions are less erythematous and may be papular rather than flat. In addition, there may be areas of postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation.

FIGURE 22.1 Atopic dermatitis involving the hand. Note the lichenfication (over the metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger) and small crusted erosions.

Individuals who have AD also commonly exhibit:

Xerosis

Hyperlinear palms

Keratosis pilaris: keratotic papules centered around follicles; typically located on the upper outer arms, thighs, and face (e-Fig. 22.2)

Dennie-Morgan lines: prominent skin folds located beneath the eyes

Ichthyosis vulgaris: polygonal scales located on the anterior and lateral legs

Lichenification: thickening of the skin with accentuated skin creases (due to chronic scratching)

Pityriasis alba: hypopigmented macules often located on the face; the borders are not sharply demarcated, rather there is a gradual transition from normal to abnormal color (e-Fig. 22.3).

Complications

Individuals who have AD are often colonized with S. aureus, likely because of increased bacterial adherence and failure to produce antimicrobial peptides. Defects in antimicrobial peptide production

and T cell function increase susceptibility to viral infections, including molluscum contagiosum, warts, and eczema herpeticum.

and T cell function increase susceptibility to viral infections, including molluscum contagiosum, warts, and eczema herpeticum.

Treatment

Daily measures:

Avoid irritants: use fragrance-free skin-care products; a non-soap cleanser for bathing (e.g., a synthetic detergent like Cetaphil or Dove bar or a lipid-free cleanser like Cetaphil, CeraVe, or Aquanil); use an additive-free laundry detergent (e.g., All Free Clear, Tide Free, and others); wear cotton clothing.

Hydrate the skin: apply a fragrance-free emollient immediately after a bath or shower. Lotions work well for many individuals but preservatives in some products may cause stinging. Creams or ointments are more effective emollients, although they may leave a greasy feel that some individuals find unpleasant.

Management of exacerbations:

Topical corticosteroid: Apply twice daily if needed. Ointments offer greater efficacy and tolerability; however, as with emollients, some patients prefer creams because ointments have a greasy feel. Prescribe a sufficient amount of product. Recall that 3 g is required to cover an entire adult arm once.

Face: use a low-potency preparation (e.g., hydrocortisone 1% or 2.5%).

Extremities or trunk: use a mid-potency agent (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% or fluocinolone acetonide 0.025%). For resistant or lichenified areas or when treating the hands, a higher-potency agent (e.g., fluocinonide 0.05% or mometasone furoate ointment 0.1%) may be needed. These agents should be used with caution since prolonged application may cause skin atrophy.

Topical calcinuerin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus [Protopic] and pimecrolimus [Elidel]):

Most useful for the management of AD in areas where potent corticosteroids cannot be used due to concerns about skin atrophy (e.g., the face, groin, axillae) or in areas of resistant disease (where they are often used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids [e.g., a topical corticosteroid is applied in the morning and the topical calcineurin inhibitor in the evening]).

Tacrolimus is indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD (the 0.03% concentration is approved for those 2 to 15 years of age and the 0.1% concentration for those ≥16 years of age); pimecrolimus is indicated for the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in those ≥2 years of age.

Antihistamine: A first-generation (sedating) antihistamine, like diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine, may be used at bedtime to provide relief from pruritus.

Antibiotic: If signs of secondary bacterial infection are present (e.g., oozing, crusting), an anti-staphylococcal antibiotic may be administered orally for 7 to 10 days. For those who have severe or resistant AD, consider attempting to reduce S. aureus colonization by recommending: (1) twice-weekly bleach baths (1/4 cup of household bleach in a half-full bathtub) and (2) intranasal mupirocin twice daily for 5 days.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common problem; the prevalence of contact allergy to at least one antigen is 20%.3 ACD occurs when an antigen penetrates the epidermis and sensitizes T lymphocytes. Within 12 to 24 hours of re-exposure to the antigen, an eruption appears at the site of contact. Often the offending agent can be identified based on the appearance of lesions and their distribution. In a minority of cases, dermatologic referral for patch testing may be necessary.

Plant (e.g., poison ivy, oak, or sumac):

Clinical manifestations: ACD due to plants results in an acute dermatitis with erythematous papules, vesicles, or bullae. Lesions are present on exposed areas (e.g., face, extremities) and may be arranged in a linear distribution (at the site of contact with resin emanating from a damaged plant) (Fig. 22.2). If the exposure is indirect (e.g., you hug a dog that has run through poison ivy), a linear distribution of lesions is absent and one sees fine erythematous papules, not vesicles.

Treatment: If the eruption is mild and limited in extent (e.g., <10% to 15% of the body surface), therapy may include a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide 0.1%), topical nonsensitizing anesthetic (e.g., pramoxine), and an oral first-generation antihistamine. When the eruption is extensive, severe, or involves critical areas (e.g., face, perineum), systemic corticosteroid therapy (e.g., prednisone orally for 12 to 21 days in a tapering dose) is indicated.

Metal: Nickel is among the most common contact allergens with a median prevalence of 8.6%.3 Allergy to nickel is more common in those who have piercings and higher rates of allergy are associated with an increased number of piercings.4 Nickel allergy produces a chronic dermatitis characterized by minimal erythema, scaling, and thickening of the skin. Commonly affected sites include the lobules of the ears (earrings), area below the umbilicus (belt buckle or clothing snap), umbilicus (piercing jewelry), neck (necklace), or wrist (bracelet or watch) (Fig. 22.3). Treatment is with an appropriate topical corticosteroid and nickel avoidance. Patients may be advised to:

Choose nickel-free jewelry and eyeglass frames (i.e., items made of surgical-grade stainless steel, solid yellow gold, titanium, or pure sterling silver).

Purchase clothing with snaps, buttons, and fasteners that are plastic or metal that is plastic coated or painted.

Wear watchbands made of plastic, leather, or cloth.

Preservatives, fragrances: These products cause erythema and tiny papules. Commonly affected sites include the face or eyelids (cosmetics), axillae (deodorant), or neck (perfume). Treatment is avoidance of the offending agent (once identified) and the application of an appropriate topical corticosteroid.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory disorder that occurs in areas with numerous sebaceous glands. It affects 1% to 3% of adults and is especially common in AYAs in whom

sebaceous glands are most active.5 Although the cause is not clearly understood, it may involve an inflammatory response to the yeasts of the genus Malassezia (formerly Pityrosporum).

sebaceous glands are most active.5 Although the cause is not clearly understood, it may involve an inflammatory response to the yeasts of the genus Malassezia (formerly Pityrosporum).

FIGURE 22.2 In contact dermatitis due to poison ivy, small erythematous papules are present, often in a linear arrangement as seen on the neck and the angle of the mandible. |

Clinical Manifestations

Typical findings are scaling of the scalp (i.e., dandruff), or scaling and erythema of the eyebrows, eyelids, glabella, nasolabial or retroauricular creases, beard or sideburn areas, or ear canals (Fig. 22.4).

Treatment

Scalp: Advise the use of an antiseborrheic shampoo containing pyrithione zinc (e.g., Head and Shoulders, DHS Zinc, and others), selenium sulfide (e.g., Selsun, Exsel, and others), or ketoconazole (e.g., Nizoral). If facial skin is involved, allow some of the shampoo to contact these areas and then rinse (this is a useful adjunct to the topical therapies discussed below). If signs of inflammation are present (e.g., erythema or erosions), a topical corticosteroid solution (e.g., fluocinolone acetonide 0.1%) may be applied at bedtime if needed.

Skin: Control can be achieved using a low-potency topical corticosteroid (e.g., hydrocortisone 1%) and/or an agent active against yeast (e.g., clotrimazole, miconazole nitrate, or ketoconazole) applied twice daily if needed.

Tinea Versicolor

Tinea (pityriasis) versicolor is a common superficial infection with yeasts of the genus Malassezia (formerly Pityrosporum). The prevalence among adults in temperate climates is 1% to 4%, but it is particularly common among AYAs in whom sebaceous glands are highly active.6 The sebum-rich environment appears to support lipophilic Malassezia spp. Although these organisms are part of the normal skin flora, hot and humid weather, sweating, and use of oils on the skin may trigger a change from the yeast form to the hyphal form, resulting in the appearance of rash.

Clinical Manifestations

Most patients have no symptoms but some report pruritus. The eruption is composed of well-defined round macules that may coalesce into large patches; scale may be present. Although lesions may be hypo- or hyperpigmented, most often, in more deeply pigmented individuals, they are hypopigmented (Fig. 22.5). The trunk is the primary site of involvement but the proximal extremities and sides of the neck may be affected. Tinea versicolor is usually diagnosed clinically. If uncertainty exists, a potassium hydroxide preparation performed on scale from a lesion will demonstrate short hyphae and spores (i.e., “spaghetti and meatballs”) and a Wood’s lamp examination will reveal a yellow-gold fluorescence of affected areas.

Differential Diagnosis

Eruptions that may be concentrated on the trunk and, therefore, mimic tinea versicolor include:

Pityriasis rosea (PR): Lesions are erythematous, oval thin plaques (not macules) with long axes oriented parallel to lines of skin stress.

Vitiligo: Lesions are depigmented (not hypopigmented) and lack scale.

Secondary syphilis: The eruption is composed of erythematous to violaceous to red-brown scaling papules. Lesions are widespread (not limited to the trunk) and often involve the

palms and soles. Affected individuals have systemic symptoms, including fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 22.5 Tinea versicolor: there are numerous round hypopigmented macules. In the supraclavicular area, macules have coalesced to form a hypopigmented patch.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: This uncommon disorder is often confused with tinea versicolor. Reticulated areas of hyperpigmentation that are hyperkeratotic (and, therefore, have a rough texture) are present on the central chest or back. Well-defined round or oval macules are not seen (e-Fig. 22.4).

Treatment

Several options exist for treatment. Because the recurrence rate may be as high as 60% in the first year, following any of the treatments listed below, prophylaxis once monthly for 3 months is warranted.6 This may be accomplished using a single 8- to 12-hour application of selenium sulfide. It is important to counsel patients that even with effective treatment, several months will be required for normalization of pigmentation.

Topical agents:

Selenium sulfide lotion 1% (available without a prescription) or 2.5% (requires prescription): Apply a thin coat to affected and adjacent areas for 10 minutes then shower. Repeat daily for a total of 7 days.

Ketoconazole shampoo: Apply for 5 minutes once daily for 1 to 3 days.

Terbinafine spray: Apply twice daily for 2 to 3 weeks.

Imidazole creams (e.g., clotrimazole, miconazole nitrate, ketoconazole, and others): Effective for very localized infection (not practical in the treatment of large areas).

Oral agents: These are usually reserved for those who have resistant infections or cannot tolerate or effectively use a topical agent. Off-label options include the following:

Itraconazole: 400 mg once or 200 mg/day for 7 days

Fluconazole: 400 mg once

Tinea Pedis (Athlete’s Foot)

Tinea pedis is the most prevalent dermatophyte infection in AYAs.

Clinical Manifestations

Interdigital form (caused by Trichophyton [T.] rubrum or Epidermophyton [E.] floccosum): Pruritus, fissuring, scaling, and maceration between the toes (Fig. 22.6)

Moccasin form (caused by T. rubrum): Widespread scaling that involves much or all of the sole and sides of the foot

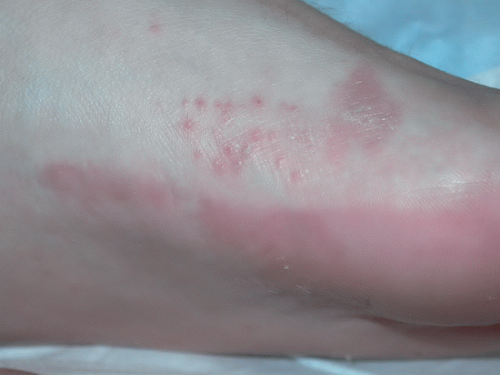

Inflammatory form (caused by T. mentagrophytes): Vesicles or bullae located on the instep of the foot (Fig. 22.7).

FIGURE 22.6 In the most common form of tinea pedis, scaling and maceration are present in the interdigital spaces. |

Differential Diagnosis

Several disorders involve the feet and, therefore, may mimic tinea pedis. In each case, a potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture would be negative.

Contact dermatitis due to shoes: Involves the dorsum of the feet, not the interdigital spaces or plantar surfaces

AD (juvenile plantar dermatosis): Typically occurs in older children and less often in adolescents. Causes erythema, dryness, lichenification, and fissuring primarily of the plantar surfaces of the forefeet

Psoriasis: Causes erythema and thick (not fine) scale of the feet. Individuals often have lesions of psoriasis elsewhere.

Treatment

For most infections a fungistatic topical imidazole (e.g., miconazole nitrate, clotrimazole, econazole, etc.) applied twice daily until clearing occurs (typically 2 to 4 weeks) is effective. If this treatment fails, consider a topical agent that is fungicidal (e.g., terbinafine, naftifine). For widespread or resistant infection, an oral agent (e.g., griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole) may be required. If there is concomitant nail involvement (i.e., onychomycosis), oral terbinafine or itraconazole will be required.

Onychomycosis

The terms onychomycosis (nail infection by any fungus) and tinea unguium (infection by fungi called dermatophytes) are often used interchangeably. The vast majority of fungal nail infections are caused by dermatophytes (usually T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and E. floccosum). The prevalence of onychomycosis is estimated to be as high as 12%.7 Infection is uncommon before puberty and highest in those >65 years of age.7

Clinical Manifestations

Two forms of infection are recognized.

Subungual onychomycosis: The most prevalent form of infection that causes thickening of the nail and a yellow discoloration distally or laterally (the result of separation of the nail from the underlying nail bed) (Fig. 22.8)

Superficial white onychomycosis: Produces a white discoloration of the surface of the nail with powdery scale.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical features of the disorders listed below often permit their differentiation from onychomycosis. However, if uncertainty exists, a fungal culture of a nail scraping or clipping can be helpful.

Candidiasis: Uncommon in adolescents and usually involves the fingernails. Causes a chronic paronychia characterized by erythema and swelling of the proximal nail fold, loss of the cuticle, and nail dystrophy (that lacks yellow discoloration).

Psoriasis: Usually causes pitting of the nails; lesions of psoriasis are present elsewhere.

Pachyonychia congenita: Results in thickening and discoloration of the nails that may be difficult to differentiate clinically from onychomycosis. The condition usually has its onset in early childhood but may be delayed until adolescence.

Lichen planus: Causes longitudinal ridging or splitting of nails. Typical skin lesions (purple polygonal papules and plaques) are present elsewhere.

Treatment

Superficial white onychomycosis may respond to topical antifungal therapy. However, subungual onychomycosis requires oral therapy and options are listed below. One should consider potential drug interactions, adverse effects, and the need for laboratory monitoring.

Terbinafine 250 mg daily for 12 weeks

Itraconazole 200 mg daily for 12 weeks

Fluconazole is preferred by some but is not US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of onychomycosis.

Cure rates with oral therapy are as high as 80%; however, recurrences are common. To reduce the chance of recurrence, advise patients to dry carefully after bathing or showering and to apply an absorbent powder containing an antifungal agent (e.g., tolnaftate [e.g., Tinactin and others], or miconazole nitrate [Micatin, Desenex, Zeasorb AF, Lotrimin AF, and others]).

Tinea Cruris

Tinea cruris represents infection of the inguinal folds with the dermatophytes T. mentagrophytes or E. floccosum. It affects men more often than women and is uncommon before puberty.

Clinical Manifestations

Appears as a well-demarcated erythematous patch involving the proximal thigh and crural fold (may be unilateral or bilateral). The border of the lesion is elevated and scaling, and is typically more erythematous than the center. The scrotum and penis are spared (Fig. 22.9).

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree