Year

Authors

Journal

Number of cases

Particularities

1995

Ohashi [1]

Surgical Endoscopy

8 cases

6 early gastric cancer, 1 submucosal leiomyoma, 1 giant polyp

2000

Hiki et al. [2]

Der Chirurg

13 cases

1 case of conversion due to intraoperative hemorrhage

2011

Sahm et al. [3]

Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech

7 cases

6 gastrointestinal stromal tumors and 1 leiomyoma

2004

Uchikoshi et al. [4]

Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech

7 cases

4 cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumors, 2 leiomyomas, and 1 schwannoma

2012

Hara et al. [5]

Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech

10 cases

1 case of conversion due to technical difficulties

2011

Shim et al. [6]

J Surg Oncol

6 cases

5 leiomyomas, and one case GIST

2011

Na et al. [7]

J Gastric Cancer

7 cases

5 gastrointestinal stromal tumors and 2 leiomyomas

The aim of this chapter is to identify the indications and to describe the technical principles of this novel technique used in our current practice. The objective is also to expand the surgeon’s armamentarium in order to safely address more complex intragastric processes while offering the benefits of minimal access surgery.

Indications

Indications for laparoscopic intragastric surgery (LIGS) can be found for all tumors, which may be resected without systematic gastrectomy or lymph node resection. It includes anecdotal foreign body removal [8, 9] and pancreatic pseudocyst drainage [10]. Typical indications include the resection of benign lesions [11–13], lesions with inconclusive pathological findings after biopsy, when malignancy cannot be ruled out [4, 14], and finally early malignancy especially at the level of the esophagogastric region [2]. At present, these tumors can be detected by different modalities (upper endoscopy, abdominal CT scan). The most frequent tumors are gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). These are frequently located at the esophagogastric junction, not easily accessible for resection via an endoscopic retroflexed view. Upper endoscopy represents the standard tool for the diagnosis of such lesions, but in certain cases its therapeutic purpose has obvious limitations. The main advantage of laparoscopic intragastric surgery is yielded by the direct approach to this region contrary to the retroflexed approach provided by endoscopy. Its limitation is not only due to the visualization of the lesion but also to the main shortcoming of the indirect endoscopic approach which is the inability to offer sufficient strength and precision to control dissection in a safe manner. Laparoscopic intragastric surgery completely overcomes such limitations and also offers an appropriate dissection angle using the basic “triangulation” principle of general laparoscopy.

Preoperative Workup

For preoperative diagnosis and surgical planning, preoperative upper endoscopy is a key step to ascertain the precise localization of the tumor. It is needed to define the anatomical landmarks of the lesions regarding the gastric curvatures, distance to the cardia, pylorus, and main vessels. The lesions are also examined by CT scan and endoscopic ultrasound (US) to determine the depth of invasion of the gastric wall. Endoscopic US is a major tool to identify contraindications represented by transmural tumors or local lymph node metastases. Finally, such data should be confirmed intraoperatively by the excellent vision provided by the laparoscopic exploration as well as by the endogastric approach.

Surgical Technique

The anatomical localization of the tumor is the most important factor to determine the ideal resection technique. When facing a tumor of the anterior gastric wall, the tumor is easy to visualize, and a tangential wedge resection through conventional transperitoneal laparoscopy is the method of choice [3]. Sometimes, the location of the tumor may be confirmed by simultaneous endoscopic exploration. If the tumor is located on the posterior gastric wall, proximal to the cardia or pylorus, a conventional wedge resection cannot be performed with appropriate margins. In this respect, intragastric surgery could well represent a valid option.

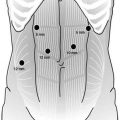

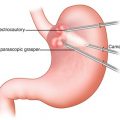

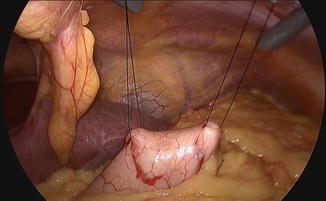

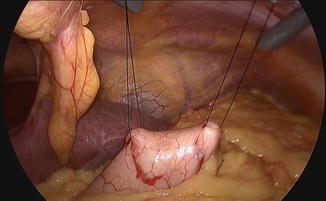

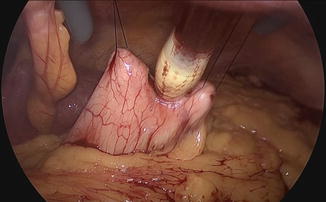

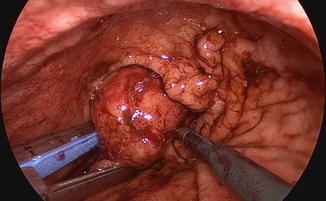

Different surgical techniques have been described for laparoscopic intragastric surgery. Our standard approach for a laparoscopic intragastric surgery is represented by a multiple intragastric port approach, as described in Video 19.1. A pneumoperitoneum is briefly established using an open access at the umbilical level. It allows to explore the abdomen and determine the ideal position of transgastric laparoscopic ports in relation to the anatomy of the stomach. Endoscopy aiming to localize the actual position of the tumor may be completed at this moment. The tumor can be located by a mark or a suture on the gastric wall. The location of the stomach wall incision is then identified. Two transparietal stitches are placed adjacent to this area and will be used to lift up the stomach and fix it to the parietal wall (Fig. 19.1). A 12 mm cuffed port is inserted into the stomach under laparoscopic guidance (Fig. 19.2). Two additional 5 mm ports are inserted and positioned to ensure triangulation in relation to the tumor’s position. The two cuffed 5 mm ports are also introduced into the stomach under direct control after partial insufflation. The peritoneal cavity is desufflated, and the stomach is explored (Fig. 19.3). There is no need for a high rate of insufflation of the stomach, as the anterior wall is lifted up by traction applied to the abdominal wall by means of stitches. Usually, no distal or proximal balloon blockage is required due to lower esophageal sphincter and pyloric resting tone. In order to achieve adequate access, multiple ports should be positioned according to general laparoscopic principles in order to achieve maximum triangulation for the dissection site. The cardioesophageal junction is a difficult location, which requires optimal visualization and triangulation of instruments for safe surgical maneuvers.

Fig. 19.1

Gastric exposure

Fig. 19.2

Intragastric trocar insertion

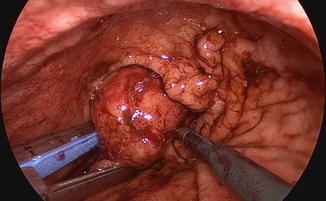

Fig. 19.3

Intragastric identification of the tumor

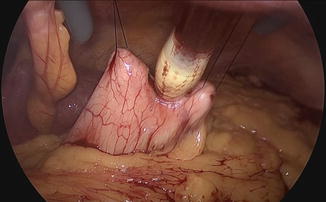

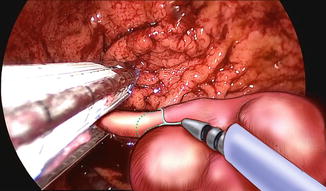

Resection and suture can be performed as a standard procedure, but most of the time, the use of stapling is preferred for many reasons, including speed, safety, and reliability as illustrated by this case (Figs. 19.4 and 19.5). It only requires the replacement of the 5 mm port by a 12 mm one. In well-selected cases (e.g., pedunculated tumors), the advantage of this technique is to obtain resection and hemostasis simultaneously, using the same instrument. However, achieving adequate margins can be difficult, and the risk of tumor rupture might be increased, particularly in case of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. In such cases, tricks including traction on the parietal gastric wall assist in achieving a full-thickness resection of the stomach wall, preserving safety margins in case of malignant lesions. The port should be positioned so that stapling can be easily accomplished in the narrow space of the insufflated stomach, and the use of roticulating staplers is mandatory. Figure 19.6 depicts the closed gastrotomy.

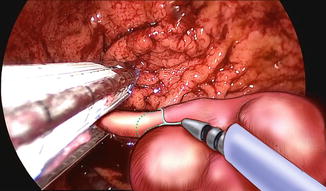

Fig. 19.4

Tumor resection

Fig. 19.5

Final stapling with suture assistance

Fig. 19.6

Gastrotomy closure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree