We report our initial experience with minimally-invasive esophagectomy in 32 patients at Carolinas Medical Center, a community academic medical center. Indications for surgery were adenocarcinoma in 27, squamous cell carcinoma in 3, and benign stricture in 2. Transthoracic Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy with laparoscopy and thoracoscopy was performed in 28, a 3-stage esophagectomy in 3, and transhaital esophagectomy in 1. There was no operative mortality and median hospital stay was 10.5 days for patients treated with minimally invasive esophagectomy. This compares with an operative mortality of 8.9% and median hospital stay of 17 days for open esophagectomy in our institution.

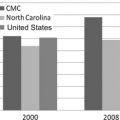

Although associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, esophagectomy remains the preferred treatment for resectable esophageal cancer. Minimally invasive techniques have been used for esophagectomy in an effort to reduce the morbidity and mortality of this complex operation. In this report, the authors describe their experience with minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) at Carolinas Medical Center, a community academic medical center serving western North Carolina and northern South Carolina.

MIE describes the use of laparoscopic or thoracoscopic techniques to mobilize the esophagus for resection and restoration of gastrointestinal continuity. These techniques were derived after recognizing the significant postoperative morbidity and mortality associated with traditional open esophageal resection. Rates of postoperative morbidity from the traditional open esophageal resection range as high as 40% to 60% with mortality rates of 5% to 20%. With the likelihood of postoperative complications, surgeons have sought to find new and different approaches with the goal of lowering overall morbidity and mortality.

Open esophagectomy techniques

The 3 most commonly performed open esophagectomy procedures are the transhiatal esophagectomy, transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) esophagectomy, and the 3-stage (McKeown) esophagectomy. All 3 operations begin with a midline laparotomy for mobilization of the stomach and formation of a gastric conduit. A transhiatal esophagectomy uses a cervical incision to mobilize the cervical esophagus. The thoracic esophagus is then mobilized by blunt dissection from the abdominal and cervical incisions. The gastric conduit is brought up to the neck and a cervical anastomosis constructed. Transthoracic esophagectomy uses a right thoracotomy to mobilize and remove the esophagus and allow creation of an intrathoracic anastomosis. A 3-stage esophagectomy uses a right thoracotomy for mobilization of the esophagus, but in addition removes the proximal esophagus and creates a cervical anastomosis.

Minimally invasive esophagectomy techniques

Increasing experience with laparoscopic surgery in the 1990s led to the development of MIE techniques. The precursor to this was the thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus in 1992 by Cuschieri and colleagues. Later work by Dallemagne combined laparoscopic and thoracoscopic resection of esophageal cancer, which led to the current techniques used in MIE. In modern practice, the 3 most frequently performed procedures for MIE include the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy with a cervical anastomosis, thoracoscopic/laparoscopic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, and laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy with a cervical anastomosis. Many variations in technique have been described.

Minimally invasive esophagectomy techniques

Increasing experience with laparoscopic surgery in the 1990s led to the development of MIE techniques. The precursor to this was the thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus in 1992 by Cuschieri and colleagues. Later work by Dallemagne combined laparoscopic and thoracoscopic resection of esophageal cancer, which led to the current techniques used in MIE. In modern practice, the 3 most frequently performed procedures for MIE include the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy with a cervical anastomosis, thoracoscopic/laparoscopic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, and laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy with a cervical anastomosis. Many variations in technique have been described.

Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy

To date, no randomized trials have compared outcomes of esophageal resection using a minimally invasive approach with open esophagectomy. Several nonrandomized comparative reports have been published, which have generally compared the two techniques with the same institution, often using historical experience within open esophagectomy. A meta-analysis of 12 comparative reports encompassing 672 MIEs and 612 open esophagectomies found shorter hospital stay, less blood loss, and fewer complications with MIE. An analysis of 1008 patients in 8 comparative studies found equivalent outcomes with the exceptions of higher stricture rate among MIE and lower overall morbidity after MIE compared with open esophagectomy. A retrospective review of 699 MIEs conducted in England between 1996 and 2008 found lower in-hospital, 30-day, and 365-day mortality as compared with open esophagectomy. Overall, the reported comparisons between MIE and open esophagectomy demonstrate MIE to be safe, with at least comparable outcomes in morbidity and mortality, and with some evidence to suggest better overall outcomes in terms of postoperative pulmonary complications, blood loss, and hospital stay. An important consideration regarding MIE for esophageal cancer is the adequacy of lymph node clearance as compared with the standard open esophagectomy. The 2 meta-analyses cited here have shown no difference in lymph node recovery rates between open esophagectomy and MIE.

Operative technique

The operative technique used for a minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy at Carolinas Medical Center is performed in 2 phases, beginning with laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach and dissection of the mediastinum from the abdomen. The technique is similar to that described by Bizekis and colleagues. The operation is conducted by 2 surgical teams including fellows and residents, each led by an attending thoracic surgeon and gastrointestinal surgical oncologist.

Abdominal Phase

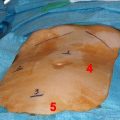

The patient is positioned supine on a split-leg table after intubation with a single-lumen endotracheal tube. The operation begins with diagnostic laparoscopy through an umbilical port to look for evidence of distant metastatic spread, especially for tumors of the gastroesophageal junction. If no signs of metastatic disease are noted, a hand port is placed between the umbilicus and xiphoid. Three 5-mm ports are placed in the left upper quadrant: the first lateral to the rectus, the second lateral to the first below the costal margin, and the third at the anterior axillary line.

The dissection is begun on entering the lesser sac though the gastrocolic omentum, avoiding injury to the right gastroepiploic artery. Lymph node tissue from around the left gastric artery is dissected and resected en bloc with the specimen. An endoscopic GIA stapler is used to divide the left gastric artery and coronary vein. The right gastric artery is preserved. The lower mediastinum is dissected with bipolar cautery. The dissection clears nodal tissue from the surfaces of the left pleura, aorta, pericardium, and right pleura, and removes this tissue in continuity with the specimen. A gastric conduit is fashioned using the endoscopic GIA stapler, which is used to divide the lesser curvature of the stomach between right and left gastric arteries. Pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy is routinely performed via the hand port incision.

Three 19F drains are left in place via the trocar sites for drainage: one into the left pleura, one into the right pleura posterior to the conduit, and one in the right abdomen inferior to the lateral segment of the liver. Finally, a 10F jejunostomy feeding catheter is placed through the abdominal wall just lateral to the rectus muscle.

Thoracic Phase

The endotracheal tube is exchanged for a double-lumen tube, and the patient is positioned in the left lateral decubitus position. A total of 5 ports are placed in the chest: camera port anterior and inferior, operating port posterior and inferior, grasping port inferior to tip of scapula posteriorly, retraction port anterior and superior, and a suction port halfway between the 2 anterior ports.

The right lung is deflated and the lung retracted to visualize the esophagus. The inferior pulmonary ligament is incised, and the pleura anterior and posterior to the esophagus is incised. Dissection proceeds to the level of the azygos vein, which is divided using a vascular endoscopic stapler. The esophagus is divided when complete dissection is achieved, and the gastric conduit is brought into the chest with the lesser curvature staple line oriented to the patient’s right. An anastomosis is created in the chest using a circular stapler. A flip-top stapler anvil affixed to a nasogastric tube (OrVil; Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA) is passed through the mouth and the distal end of the tube brought through a fenestration in the esophageal staple line. The superior end of the lesser-curve staple line is opened, and a 25-mm stapler inserted through the posterior-inferior thoracic port. The stapler head is inserted through the opening in the lesser curvature, and its spike brought out through the greater curvature of the gastric conduit. The stapler components are mated and fired. The opening in the lesser curvature is reapproximated with a GIA stapler.

Three-Stage Esophagectomy

If a 3-stage esophagectomy is required because of the extent of disease, the operation begins with laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach and dissection of the lower mediastinum from the abdomen. The patient is then positioned laterally, and the thoracic esophagus dissected. The patient is then repositioned supine and a cervical incision is made, the proximal esophagus circumferentially dissected and divided, and the gastric conduit passed from the abdomen to the chest. A cervical anastomosis is constructed with a linear stapler.

Transhiatal Esophagectomy

For patients with early-stage disease who do not need a mediastinal lymph node dissection, a transhiatal esophagectomy is performed using laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach and construction of a gastric conduit. The lower mediastinum is dissected using laparoscopic instruments. The dissection from below is completed using a hand inserted through the hand port. The specimen is removed after simultaneous dissection from the abdominal and cervical incisions. A cervical anastomosis is constructed with a linear stapler.

Postoperative care

All patients are admitted to the surgical intensive care unit for postoperative monitoring, where they are cared for in coordination with a group of surgical intensivists who provide around-the-clock coverage. Central venous and arterial lines are placed by anesthesia before the operation and are used for invasive hemodynamic monitoring in the postoperative period. Swan-Ganz catheters are not routinely placed for monitoring purposes. To a varying degree patients are left intubated in the immediate postoperative period; those patients with adequate presurgical pulmonary function undergo attempted extubation immediately after the operation. Those patients left intubated are weaned from the ventilator expeditiously with the goal of extubation on postoperative day 1. Beginning on the day of surgery, tube feeds are started at via the jejunostomy tube. Patients are given standard perioperative antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and β blockade. For pain control, an epidural is placed before induction of anesthesia.

On the first postoperative day, patients are started on low molecular weight heparin and feeding via jejunostomy tube is initiated. Ambulation is encouraged and patients are asked to sit in a chair. Patients are assessed for ability to transfer to the surgical ward with the goal of transfer on the second postoperative day.

On postoperative day 4, patients undergo a standard esophagogram under fluoroscopy with water-soluble contrast to assess for anastomotic leak and emptying of the conduit. The epidural catheter is removed on postoperative day 5, along with the urinary catheter. On postoperative day 7, patients undergo computed tomographic (CT) esophagography to assess again for anastomotic leak. After a normal CT esophagogram, the pleural drains are removed. Patients are discharged with nocturnal tube feedings. The tube feedings are weaned over the next 4 to 6 weeks in an outpatient setting. When possible, discharge is planned for postoperative day 9.

Outcomes

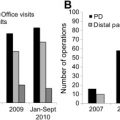

A total of 32 patients underwent some variant of MIE. Two patients early in the authors’ experience underwent a hybrid procedure with laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach followed by thoracotomy. Transthoracic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with laparoscopy and thoracoscopy were performed in 28. A 3-phase esophagectomy was performed in 1 patient and laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy in 1. Indications for operation were adenocarcinoma in 27 patients, squamous cell carcinoma in 3, and benign stricture in 2. Conversion to laparotomy and thoracotomy was necessary in 1 patient due to extensive adhesive disease, and conversion to thoracotomy was necessary in 1 patient due to bleeding. The mean age was 58 (range 22–71) years. Mean intraoperative blood loss was 380 mL. Major complications occurred in 13 patients (42%), as shown in Table 1 . Delayed complications occurred in 2 patients, one of whom developed delayed gastric emptying after a pyloromyotomy and underwent a laparoscopic pyloroplasty. Another patient who did not undergo a drainage procedure at the time of esophagectomy was treated with a laparoscopic pyloromyotomy.