Microtubule Inhibitors

Timothy M. Dang

Daniela Kroshinsky

Microtubule inhibitors are comprised of largely two classes of chemotherapy—taxanes and vinca alkaloids. Taxanes are cytotoxic drugs that promote the polymerization of tubulin into stable microtubules, which disrupts mitosis and results in cell death.1 These drugs are approved and widely used to treat many different malignancies, including ovarian, breast, lung, gastric, and head and neck cancers. Drugs in this class include paclitaxel, docetaxel, and cabazitaxel. A nanoparticle albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), which does not require the use of solvents, is also available.

Vinca alkaloids are cytotoxic drugs that bind to tubulin and inhibit microtubule formation, which disrupts mitosis and results in cell death.2 These drugs are also approved to treat diverse malignancies, including acute leukemia, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, breast cancer, and testicular cancer. Drugs in this class include vincristine, vinblastine, and vinorelbine.

Common dermatologic adverse effects associated with taxanes and vinca alkaloids include hypersensitivity reactions, alopecia, nail changes, and extravasation reactions. Moreover, a clinically distinct form of hand-foot syndrome (HFS) with a predilection for dorsal surfaces is also common with taxane therapy. Rarely, taxanes can induce sclerosis of the skin.

Taxane-induced hypersensitivity reactions are relatively common, even with standard premedication (e.g., antihistamines). These reactions usually occur within minutes after starting the infusion and may be triggered by solvents used to solubilize these drugs, which are otherwise hydrophobic. Manifestations include systemic symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, hypotension), flushing, urticaria, morbilliform or urticarial eruptions, and pruritus.

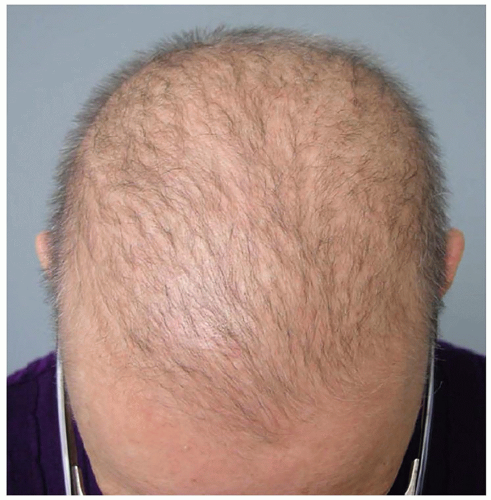

Alopecia is also a very common adverse effect of both taxane and vinca alkaloid therapy and can manifest as anagen effluvium within weeks after starting therapy. Though hair regrowth often occurs by 6 months after therapy, hair loss and hair changes (e.g., texture and color change) may be persistent (Figure 26.1); persistent chemotherapy induced alopecia (pCIA) is most commonly associated with taxanes.

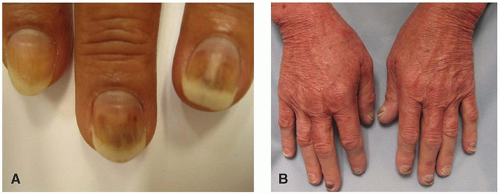

Nail changes are commonly observed in patients on taxane chemotherapy and can manifest within weeks after starting infusion.1 These changes include splinter hemorrhages, subungual hemorrhages, onychorrhexis (longitudinal thickening and thinning of the nail plate), onychoschizia (horizontal splitting of the nail plate), onycholysis (distal lifting of the nail plate), Beau’s lines (horizontal ridges in the nail plate), melanonychia, erythronychia, leukonychia, and paronychia. Secondary infection can occur due to compromise of the nail plate barrier (Figure 26.2).

A clinically distinct form of HFS can also develop due to taxane therapy.1 Onset is variable and dose dependent. In contrast to HFS associated with other cytotoxic agents

(e.g., capecitabine, doxorubicin), the taxane variant has a predilection for dorsal surfaces. Manifestations include prodromal pain and paresthesia that progress to erythematous plaques and desquamation (Figure 26.3).

(e.g., capecitabine, doxorubicin), the taxane variant has a predilection for dorsal surfaces. Manifestations include prodromal pain and paresthesia that progress to erythematous plaques and desquamation (Figure 26.3).

Figure 26.1. Persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia with failure to recover more than half of hair lost during treatment with a taxane-based regimen. (Photo courtesy of Milan Anadkat, MD.) |

Figure 26.2. Distal onycholysis and subungual hemorrhage characteristic of taxane therapy in a breast cancer patient (A). Erythema of the dorsal hands with all 10 nails affected by onycholysis, some with subungual hemorrhage and the left thumb with purulent secondary infection (B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|