Metastatic Cancer of Unknown Origin

James M. Leonardo

The primary site remains unknown in about 5% to 10% of patients with newly diagnosed cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer), despite a detailed pretreatment evaluation. Even after extensive evaluation and postmortem examination, a primary tumor is not found in up to 30% of these patients. However, the frequency of cancers with truly occult primary sites is decreasing, in part because of advances in technology to detect the primary site(s). The problem of metastatic cancer of unknown origin raises difficult questions for both diagnosis and treatment Although the median survival time of patients with cancer of unknown origin has been reported to be 6 to 9 months, subgroups of patients have been defined who have a more favorable outlook with aggressive management. With current therapy modalities, the overall survival of these patients appears to be improving. A major responsibility of the clinician is to identify those patients with a characteristic presentation who might benefit from a specific strategy and to identify the increasingly large group of patients who might benefit from a trial of chemotherapy.

Tumors thought to be more amenable to treatment, and thus have a more favorable prognosis, include poorly differentiated cancers with midline distribution, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) involving cervical lymph nodes, papillary adenocarcinoma of the peritoneal cavity in women, and adenocarcinoma involving only axillary lymph nodes in women. Conversely, adverse prognostic findings include adenocarcinoma metastatic to the liver or other organs, nonpapillary malignant ascites, and multiple metastases to brain, bones, or lungs.

I. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS AND AIMS OF THERAPY

A. Histology and presenting clinical manifestations

Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma and poorly differentiated carcinoma or adenocarcinoma respectively comprise up to 60% and 30% of all cancers of unknown origin. SCC and poorly differentiated cancers other than adenocarcinoma each account for about 5% of unknown primary tumors. Other histologies that may present as cancer of unknown origin include lymphomas, germ cell tumors, and neuroendocrine carcinomas. These histologies are particularly important to identify because they represent tumors that may be effectively managed with systemic chemotherapy. Nearly half of all patients with unknown primaries and well over

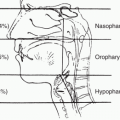

half of those with adenocarcinoma present with hepatomegaly, abdominal mass, or other abdominal symptoms. Lymphadenopathy is the presenting clinical manifestation in 15% to 25% of patients. Lower cervical or supraclavicular lymph nodes usually contain adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma, and middle to high cervical adenopathy generally represents SCC. Between 10% and 20% of patients present with manifestations of bone, lung, or pleural involvement, whereas fewer than 10% present with evidence of central nervous system disease. Most of the latter group is eventually found to have either lung or gastrointestinal tract primaries.

A few presentations of advanced carcinoma of unknown primary site have been recognized as being more treatable and thus having a more favorable prognosis than others. Poorly differentiated carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, especially with predominant sites of involvement in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, lymph nodes, or lungs, and adenocarcinoma in women predominantly involving the peritoneal surfaces may respond to platinum-based chemotherapy regimens designed for germ cell or ovarian cancers and result in occasional long-term disease-free survival. Women with axillary adenopathy and adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma may occasionally enjoy sustained responses to therapy directed against breast cancer.

B. Sites of origin

It is sometimes possible to predict the most likely primary sites from the histology and location of the metastatic lesion of unknown origin. Pancreas and lung are the most common ultimately determined sites of origin. Together, they represent more than 40% of the adenocarcinomas of unknown origin in which the site can be ultimately determined. Colorectal, gastric, and hepatobiliary carcinoma each represent about another 10%.

In general, adenocarcinomas or undifferentiated carcinomas presenting with hepatic metastases or left supraclavicular adenopathy are eventually demonstrated to be of gastrointestinal origin. SCCs that present in the supraclavicular or low cervical lymph nodes are usually from lung primaries, whereas similar lesions of higher cervical nodes are more likely to have originated from occult primary lesions in the head and neck region.

The pattern of metastatic involvement associated with occult primary tumors may differ from that associated with overt primaries. For example, occult lung cancer rarely involves bone, a common site of metastasis from overt lung cancer; however, bone metastases appear to be more common in patients with gastrointestinal cancer who have occult primaries than in those who have overt primaries. Nonetheless, occult primaries can metastasize to any site and, in general, one should not rely on the pattern of metastatic spread to predict the site of origin.

C. Aims of diagnostic evaluation

The first objective in the management of a patient newly diagnosed with cancer of unknown origin is to plan the appropriate diagnostic evaluation. There are three chief aims of this evaluation:

1. Identify a tumor in which cure or effective disease control is possible.

2. Determine if the tumor is regionally confined or widely metastatic. 3. Identify any complication for which immediate local therapy is indicated.

D. Goals of treatment

In patients with tumors for which effective systemic therapy is available and in patients with disease regionally confined to peripheral lymph nodes alone, the primary goal of treatment is prolongation of life through extended disease control; in some cases, cure should be considered. These patients represent approximately 25% of patients with occult primaries. For the remaining patients, the chance of prolonging life has been less likely, but with the advent of new cytotoxic agents and targeted drugs, prospects for this group are improving. Treatment should also address palliation of symptoms and preservation of the best possible quality of life.

II. DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

A. Initial workup

The initial evaluation of a patient presenting with a metastatic tumor should include a complete history and physical examination including a breast, pelvic, and rectal examination in women and prostate and testicular examination in men. Routine laboratory studies (complete blood count, electrolytes, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and calcium, as well as liver function testing) should also be done early on in the evaluation. The clinical scenario should determine whether more specialized laboratory testing is appropriate. It is wholly reasonable to measure cancer antigen (CA)-125 in the setting of a woman with ascites, for example. Imaging studies should include a chest radiograph at minimum; additional studies such as mammography may be useful depending on the location of the metastases and symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is now being routinely used to evaluate patients with occult primary tumors and may be responsible for the decreased frequency of cancers that remain of truly unknown origin. The role of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scanning is not clear, but some series have reported a usefulness of this modality for identifying the primary site, particularly when the presentation is in cervical lymph nodes. Although not recommended as part of the routine evaluation of all patients with occult primary cancers, PET-CT scans may be particularly useful with occult primary tumors with a single site of metastasis when therapy

with a curative intent is planned. More invasive testing, such as bronchoscopy, endoscopy, or colonoscopy, should be guided by the patient’s symptoms.

B. Analysis of the biopsy specimen

If possible, the pathologist should receive fresh, unfixed material to allow electron microscopy, histochemistry, immunohistology, and hormone receptor studies to be done, if needed, after routine examination. Careful review of the biopsy material should be undertaken to attempt to classify the tumor conclusively as SCC, adenocarcinoma, or other identifiable histology. Up to 40% of cancers of unknown origin are undifferentiated or poorly differentiated tumors based on evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin-stained material. Electron microscopy, when available, may be useful for the further classification of these tumors through the identification of desmosomes and intercellular bridges (SCC); tight junctions, microvilli, and acinar spaces (adenocarcinoma); premelanosomes (amelanotic melanoma); neurosecretory granules (small-cell or neuroendocrine carcinoma); and absence of junctions (lymphoma). Immunohistochemistry is an indispensable part of the evaluation of carcinoma of unknown primary site. The expression of cytokeratins, particularly CK7 and CK20, may be useful in narrowing down the origin of a tumor. Immunohistochemical studies on the tumor may be used to demonstrate the presence of prostatic acid phosphatase or prostate-specific antigen (PSA; prostate carcinoma), human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG; germ cell tumors), α-fetoprotein (germ cell tumors or hepatocellular carcinoma), or monoclonal immunoglobulin (lymphoma, plasmacytoma). Immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene rearrangements may be helpful in identifying tumors of lymphoid origin. Undifferentiated carcinomas or adenocarcinomas in women should be evaluated for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Mucin positivity is helpful in eliminating the possibility of renal cell carcinoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree