Men’s Health

William P. Adelman

KEY WORDS

Epididymitis

Hydrocele

Male genital examination

Men’s health

Scrotal masses

Scrotal swelling

Spermatocele

Testicular self-examination

Testicular torsion

Varicocele

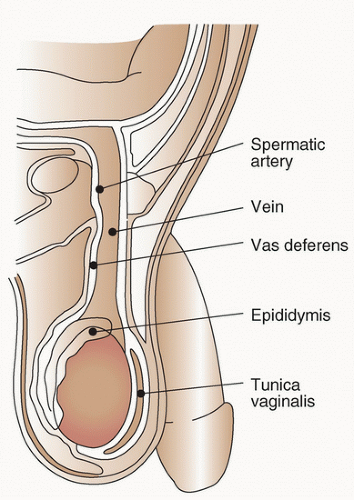

Examination of the male genitalia is a crucial part of the examination of the teenager and young adult. It is necessary to assess growth and development, to identify common variants and abnormalities, and is recommended by national organizations as part of adolescent and young adult (AYA) primary care.1,2,3,4 It is a relatively easy examination to learn because the male genitalia are readily accessible for palpation and the anatomy is straightforward (Fig. 54.1). Once the anatomy is understood, a history and physical examination are often all that are required to make an accurate diagnosis. If the anatomy of the presenting condition is unclear, due to inability to perform a complete examination or loss of usual landmarks, ultrasonography is a simple, noninvasive method to clarify anatomy. Before beginning the examination, the examiner should make sure that his or her gloved hands are warm.5,6

Inspection

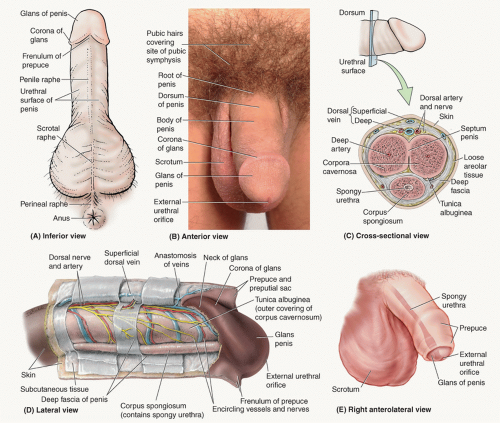

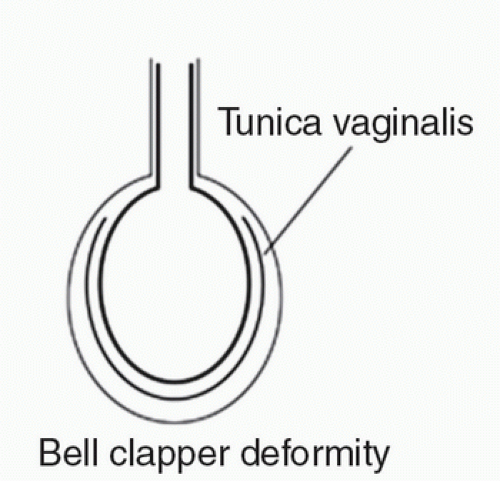

Inspect the pubic hair area and underlying skin noting sexual maturity rating (SMR).5,7 Next, inspect the groin and inner aspect of thighs, followed by the penile meatus, prepuce, glans, corona, and shaft (Fig. 54.2). It is best to have the uncircumcised patient retract his own foreskin. Uncircumcised males have higher prevalence rates of pearly penile papules as well as ulcerative sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Pink, pearly penile papules are benign, uniform-sized papules that arise most commonly along the corona, during SMR 2 or 3, in as many as 15% of teenagers (Fig. 54.3). Inspect the scrotum and recognize that contraction of the dartos muscle of the scrotal wall produces folds or rugae, most prominent in the younger adolescent. An underdeveloped scrotum may indicate an ipsilateral undescended testicle. With a retractile testicle, the scrotum is normally developed. Finally, inspect the testes—the left testis is usually lower than the right. Check for enlargement (tumor, infection, hydrocele, or hernia) or asymmetry, suggesting atrophy or cryptorchidism on one side or unilateral enlargement as seen in tumor. Check for a “transverse lie” or “horizontal lie” of the testis, suggesting a “bell clapper deformity” (Fig. 54.4) and increased risk for torsion.

Palpation

Palpate the inguinal area, spermatic cord, epididymis, testes, and external inguinal ring. Check for lymphadenopathy or hernia in the inguinal area. In order to palpate the spermatic cord, apply gentle traction on the testis with one hand and palpate the structures of the cord with the index or middle finger and thumb of the opposite hand. The vas deferens feels like a smooth, rubbery tube and is the most posterior structure in the spermatic cord. Thickening and irregularity of the vas deferens may be caused by infection. Check for a varicocele (dilated pampiniform plexus of veins) within the spermatic cord. The epididymis lies along the posterolateral wall of the testis. The head of the epididymis attaches at the superior pole of the testis. The epididymis becomes the vas deferens and leaves the testis as part of the spermatic cord. The easiest way to find the epididymis is to follow the vas deferens toward its junction with the tail of the epididymis. Tenderness, induration, and swelling in this area usually indicate epididymitis. A well-localized, nontender, spherical enlargement of the epididymal head is a spermatocele. Palpate the testes to check size, shape, and presence of tenderness or masses. The adult testes are approximately 4 to 5 cm long and 3 cm wide but vary from one person to another. Stabilize the testis with one hand and use the other hand’s thumb and first two fingers to palpate the entire surface. The testes should be roughly the same

size (within 2 mL in volume), and volumes vary according to pubertal stage. Testicular volume could be quantified with the use of an orchidometer or by ultrasound. Any induration within the testis is suspicious of testicular cancer until proved otherwise. The appendix testis, present in 90% of males, can sometimes be palpated at the superior pole of the testis. Palpate the external inguinal ring by sliding your index finger along the spermatic cord above the inguinal ligament while having the patient cough or strain to check for a hernia.

size (within 2 mL in volume), and volumes vary according to pubertal stage. Testicular volume could be quantified with the use of an orchidometer or by ultrasound. Any induration within the testis is suspicious of testicular cancer until proved otherwise. The appendix testis, present in 90% of males, can sometimes be palpated at the superior pole of the testis. Palpate the external inguinal ring by sliding your index finger along the spermatic cord above the inguinal ligament while having the patient cough or strain to check for a hernia.

Cryptorchidism refers to an undescended testis that cannot be drawn into the scrotum.8

Epidemiology

Cryptorchidism is the most common genitourinary disorder of childhood, with a prevalence of 0.7% after 9 months of age.

Diagnosis

When a testis is not palpable in the scrotum, gentle massage should be performed along the line of descent from the anterosuperior spine, medially, and downward to the pubic tubercle. If the testis is not truly undescended, it should become palpable in the scrotum. If cryptorchidism is present, the teen should be examined for stigmata of associated disorders (i.e., Noonan, Klinefelter, or Kallmann syndrome or trisomy 13, 18, or 21).1,5

Complications

Infertility

Sperm production in the cryptorchid testis may be significantly impaired compared with normal testicular function, regardless of patient age at the time of discovery.

Malignancy

About 5% to 12% of all malignant testicular tumors occur in males with a history of an undescended testis. The relative risk of tumors

in such individuals is increased approximately 10 to 40 times that of a male without cryptorchidism. Moreover, the risk is increased even if the testis is brought down into the scrotum.

in such individuals is increased approximately 10 to 40 times that of a male without cryptorchidism. Moreover, the risk is increased even if the testis is brought down into the scrotum.

Therapy

Therapy for cryptorchidism in teenagers should be corrective surgery. These teens should be aware of the increased risk of testicular cancer and may be taught testicular self-examination.

Evaluation

The general approach to the adolescent or young adult with a scrotal mass or a painful scrotum (Fig. 54.5) includes a directed history, physical examination, and laboratory testing.5,9

History

The adolescent or young adult should be questioned regarding the presence and prior history of genitourinary anomalies, pain, trauma, change in testicular or scrotal size, and sexual activity. Abrupt onset of pain is suggestive of torsion; gradual onset suggests epididymitis or orchitis; lack of pain suggests a tumor or cystic mass. Torsion is often preceded by episodes of mild pain. Reactive hydroceles are common secondary to trauma, orchitis, testicular cancer, and epididymitis, and are noted as changes in the scrotum. Epididymitis in adolescence and young adulthood is usually sexually transmitted.

Physical Examination

Inspection of the testes can differentiate torsion from infection. In torsion, the affected testis is often higher than on the contralateral side. With infections, the affected testis is often lower. In torsion, the affected testis and often the contralateral testis lie horizontally instead of in the usual vertical position, secondary to the congenital defect involved, and the epididymis is usually displaced anteriorly, as the testis twists on its vascular pedicle. Careful palpation of the testicular surfaces, the epididymis and cord (posterior structures), and the head of the epididymis (superior structure) can further identify the cause of the painful mass. Isolated swelling and tenderness of the epididymis suggest epididymitis. A tender, pea-sized swelling at the upper pole of the testis suggests torsion of the appendix testis. Generalized swelling and tenderness of both the testis and the epididymis can be found in either testicular torsion or epididymitis with orchitis. Presence of a cremasteric reflex makes torsion unlikely. However, it is often present in torsion of the appendix testis. Prehn’s sign, the relief of pain with elevation of the testis, suggests epididymitis. Lack of pain relief with elevation of the testis is not a reliable test for torsion. Nausea or vomiting with testicular pain is usually caused by torsion.

If a painless mass is present (Fig. 54.5), palpate to assess its location and then transilluminate the mass. Important findings on physical examination include the following: a mass within the testis is a tumor until proved otherwise; a mass palpable separate from the testis is unlikely to be a tumor; a “bag of worms” or “squishy tube” along the left spermatic cord is a varicocele; a mass located near the head of the epididymis, above and behind the testis is probably a spermatocele; a mass anterior to or surrounding the testis is probably a hydrocele; or a mass that is separate from the testis/epididymis, enlarges with straining (Valsalva), and is reducible is probably a hernia. Transilluminate the mass with a light source. Clear transillumination suggests a hydrocele or a typical spermatocele, whereas absence of transillumination suggests a testicular tumor or, if the mass is separate from the testis/epididymis, a hernia or a large spermatocele.

Laboratory Evaluation

A painful scrotum, or dysuria, a urine dipstick test that is positive for leukocyte esterase, or the presence of leukocytes on microscopy (especially if there are >20 white blood cells/high-power field) is suggestive of epididymitis rather than torsion. If a reasonable suspicion of torsion exists, emergent urology consultation is warranted. One should not delay this referral by ordering diagnostic tests, as the primary therapy should be surgical exploration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree