I. MELANOMA

A. Natural history

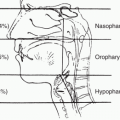

1. Etiology and epidemiology. Melanoma arises from pigmentproducing melanocytes that migrate to the skin and eye from the neural crest during embryologie development. Approximately 5% of melanoma occurs in noncutaneous sites such as the eye and mucous membranes of the oropharynx, sinuses, vagina, and anus. Patients can present with regional lymph node involvement or distant metastatic disease without any primary being identified. This occurs in approximately 5% of patients. Melanoma occurs more commonly in men than women and has a peak age at incidence of approximately 50 years. Owing to the young age of many melanoma patients, this disease takes a striking toll in terms of the average number of years of life lost per patient in the United States. The incidence of the disease has increased in the United States to the point where melanoma is now the sixth most common cancer in men or women. The substantial increase in incidence is presumably due to increased

exposure to sunlight (primarily ultraviolet B radiation), with the greatest risk of melanoma felt to be in those who have intermittent intense sun exposure, particularly in fair-skinned, lighthaired individuals with red and blonde hair, and blue or green eyes. The cultural emphasis on sun-tanned skin as an indicator of physical health and beauty has played a major role in this increase. Depletion of the ozone layer may contribute as well. Sunny parts of the United States have the highest incidence of the disease, especially California, Florida, Arizona, and Texas, which include three of the four most populous states in the United States. One particular melanoma subtype, lentigo maligna melanoma, which often occurs on the face, may be more closely associated with long-term occupational sun exposure and is seen in farmers and other outdoor workers. Patient education in prevention, including use of sun-protective clothing, performing outdoor activities at times other than the brightest sunlit hours of the day, use of topical sunscreens, refraining from use of sun-tan parlors, use of skin self-examination, and avoiding sun-tanning (“tanned skin = damaged skin”), should be emphasized. Individuals with xeroderma pigmentosa, an autosomal recessive disorder, typically incur multiple basal and squamous skin cancers and melanoma because their skin lacks the ability to repair damage induced by ultraviolet radiation.

2. Precursor lesions, genetics, and familial melanoma. Melanomas arise not only from sporadic or familial atypical nevi but also from other congenital and acquired nevi; however, approximately half of cutaneous melanomas arise without a clear cut precursor lesion. Individuals who have more than 20 benign nevi are at increased risk for melanoma. Approximately 10% of patients with melanoma have a family history of this cancer. Careful surveillance should be carried out in patients with these risk factors. Suspicious-appearing lesions or lesions that appear to have changed coloration, shape, height, or have bled should be excised. The familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome is characterized by a young mean age at diagnosis (34 years) and multiple lesions. The most common germline mutation seen in familial melanoma occurs in the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2A. CDKN2A, PTEN, NRAS, and BRAF mutations have also been seen in nonfamilial melanoma.

3. Types and appearance of primary lesions. Clinical features, classically known as “ABCD,” that raise suspicion for melanoma include:

Asymmetry of a lesion

Borders that are irregular

Color that is multihued

Diameter greater than 6 mm (i.e., “larger than the diameter of a pencil eraser”).

Other characteristics of concern include history of recent growth, change in pigmentation, ulceration, itching, or bleeding. Any pigmented lesion that returns after excision should be reevaluated with biopsy. Nonpigmented skin lesions that behave like melanoma should be examined with immunohistochemical stains S-100 and HMB-45 as 1% to 2% of melanomas are amelanotic.

There are four clinical types of primary cutaneous melanoma. Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type, accounting for 70% of melanomas. It is commonly found on the trunks of men and lower extremities of women. Nodular melanoma comprises 10% to 15% of melanomas and has an early vertical growth phase. It is commonly found on the trunks of men. Those lesions associated with intermittent sun exposure are often (50% to 60%) B-RAF mutated but C-KIT wild-type. Lentigo malignant melanoma accounts for approximately 10% of cases. It is characterized by flat, large (1- to 5-cm) lesions located on the arms, hands, and face of the elderly (median age 70 years) in particular and is known for a relatively longer radial phase. Acral lentiginous melanoma is seen in approximately 3% to 5% of cases and occurs primarily on the palmar surfaces of the hands, plantar surfaces of the feet, and under nails on the digits. This melanoma subtype is most commonly seen in individuals with darker-pigmented skin and is felt not to be as closely related to sun exposure as the other subtypes. Mutations in exons 9 and 11 of the C-KIT gene are more commonly observed in acral lentiginous and mucosal melanomas than other subtypes, but still only occur in about 20% to 30% of these cases.

In general, melanoma is felt to show two distinct growth phases: an initial radial phase during which the melanoma enlarges in a horizontal/superficial pattern above the basal lamina of the skin, followed eventually by a vertical growth phase characterized by invasion deeply with exposure to lymphatic vessels and the vasculature. It is during the vertical growth phase that metastases are felt to be most likely to occur.

4. Patterns of metastases. Melanoma has a proclivity for direct nodal spread presumably through the lymphatics, but a significant proportion of lesions exhibit hematogenous spread as well. Common sites of metastases include lung, liver, bone, subcutaneous areas, and, primarily in late stages, brain. However, melanoma can spread to virtually any site and can imitate virtually any solid malignancy in its pattern of spread. Following diagnosis, approximately 25% of patients will develop visceral metastases. An additional 15% may develop disease limited to lymph nodes. Patients who present with lymph

nodal or metastatic involvement without any obvious primary site may have undergone spontaneous remission of the primary, a phenomenon that may be attributable to some degree of immune system involvement. Interestingly, those patients may have a better outcome than similarly staged patients with known primaries. Patients with “cancer of unknown primary” should have their biopsy material analyzed with the immunohistochemical stains S-100 and HMB-45 to consider the possibility of melanoma.

5. Ocular melanoma. Ocular melanoma is the most common malignancy of the eye in adults. It may occur in any eye structure that contains melanocytes, although uveal tract sites predominate, followed by choroid, ciliary body, and iris in decreasing frequency. Standard therapy may consist of either enucleation (often utilizing a “no touch” technique) or brachytherapy with radioisotopes such as iodine-125. A recently published large randomized study of those two treatments revealed that for primary uveal tumors less than 5 mm in depth, the outcome for survival was identical. This tumor metastasizes most frequently to the liver and appears to be no less sensitive to both biologic agents and chemotherapy than is cutaneous melanoma.

B. Staging

Melanoma is staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system (see Tables 14.1,14.2 and 14.3). All patients should have a careful history and physical examination with special attention to the skin including scalp, mucous membranes, and regional lymph nodes. Laboratory studies should include complete blood count, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, liver panel, alkaline phosphatase, and serum lactate dehydrogenase at baseline. A baseline chest radiograph is obtained to evaluate for pulmonary lesions. A computed tomography (CT) scan can be considered if clinically warranted. Elevation of liver function tests warrants further imaging of the liver, most typically with CT. Unexplained bone pain should also be evaluated with CT or magnetic resonance imaging. Primary lesions equal to or thicker than 1.0 mm are at higher risk of regional lymph node involvement; therefore, the use of sentinel node mapping is recommended for lesions between 0.76 and 1 mm and above.

C. Surgical treatment

The standard treatment for skin lesions suspected of being melanoma is excisional biopsy rather than incisional or “shave” biopsies. A subsequent wide and deep excision is required to provide adequate tumor-free margins as melanoma has a known propensity for local recurrences. While there is some variation in recommendations, most experts would advocate a 1-cm tumor-free margin for melanomas less than 1 mm in thickness and 1- to 2-cm margins for deeper primary lesions if technically possible, following current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. Additionally, for primary lesions of at least 1 mm, sentinel node mapping is recommended. Lymph node “drainage areas” are assessed via a specific lymph node (sentinel node(s)—sometimes more than one) into which lymphborne metastases generally first occur. The absence of tumor involvement in the lymph node is associated with a reduced risk of nodal spread and relapse in general and eliminates the need for subsequent dissection of that nodal basin. In the recent MultiCenter Sentinel Lymph Node Trials 1, 1347 patients with primary melanomas of 1.2 to 3.5 mm, felt to be at intermediate risk of recurrence, were randomly allocated to receive either observation or a sentinel node biopsy, with completion lymphadenectomy if the sentinel node was positive and observation only if negative. A delayed lymph node dissection was performed in case of nodal recurrence in either group. Preliminary results from that trial suggest that there was no survival advantage for the performance of a sentinel lymph node biopsy in this risk group, although it reduced the relative risk of recurrence at any site by 26%, reduced the absolute chance of recurrence locoregionally from 15.6% to 3.4%, and confirmed that those with a positive sentinel node had a worse outcome than those with a negative sentinel node biopsy.

TABLE 14.1 TNM Classification for Melanoma

T Status Classification

Thickness (mm)

Ulceration

T1

≤1.0

a = no ulceration and mitosis <1/mm2

b = with ulceration or mitosis ≥1/mm2

T2

1.01-2.0

a = no ulceration

b = with ulceration

T3

2.01-4.0

a = no ulceration

b = with ulceration

T4

>4.0

a = no ulceration

b = with ulceration

N Status Classification

Number of Lymph Nodes

Involvement

N1

1

a = microscopic

b = macroscopic

N2

2-3

a = microscopic

b = macroscopic

c = “in-transit” or “satellite” present but no lymph nodes involved

N3

≥4

This classification applies also if “in-transit” or “satellite” lesions present with metastatic nodes.

M Status Classification

Metastatic Site

Serum LDH

M1a

Distant subcutaneous, skin, or node

Not elevated

M1b

Lung

Not elevated

M1c

All other visceral sites

Not elevated

M1c

Any

Elevated

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC. AJCC cancer staging manual(7th ed.). New York: Springer; 2010.

TABLE 14.2 Clark Levels of Invasion

Level

Description

I

Limited to the epidermis

II

Invades papillary dermis

III

Extends to papillary—reticular dermal junction

IV

Invades reticular dermis

V

Invades subcutaneous fat

TABLE 14.3 Approximate Survival in Melanoma Based on Stage Grouping

Stage

TNM (Pathologic)

Five-Year Survival (%)

IA

T1a

95

IB

T1b

90

T2a

89

IIA

T2b

77

T3a

IIB

T3b

65

T4a

IIC

T4b

45

IIIA

N1a

53

N2a

49

IIIB

N1b

51

N2b

46

IIIC

N3

27

IV

M1a

19

All others

M

<10

From Balch CM, Gershenwal JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2199-2206.

D. Adjuvant therapy

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) protocol E1684 was a large randomized adjuvant trial of interferon (IFN)-α2b in patients with deep primary lesions (>4 mm thick) or regional lymph node involvement that showed statistically significant improvement in overall survival in the treated group compared to the observation group. The regimen used was IFN 20 million IU/m2 intravenously (IV) 5 days/week for 4 weeks (as a “loading phase”) followed by 10 million IU/m2 subcutaneously (SC) 3 days/week for 48 weeks as a maintenance phase. Toxicity was significant, but quality-oflife analysis demonstrated overall benefit. The follow-up study of observation versus the same IFN regimen versus a lower dose regimen, ECOG 1690, also showed a significant disease-free survival advantage over the observation arm but not a benefit in overall survival for the high-dose regimen. The difference between these two studies may be that patients on the observation arm in the subsequent trial (1690) may have been treated with immunotherapy (including IFN or interleukin [IL]-2) at the time of relapse. Several recent meta-analyses of randomized trials of high-dose IFN have shown that while there is a statistically significant and consistent advantage in relapse-free survival, the benefit for overall survival is very modest, at 2% to 3%. Nonetheless, given that patients with deep cutaneous primaries and/or lymph node involvement are at high risk for metastatic recurrence and that the majority of patients who suffer metastatic relapse will die of their disease, it is reasonable to treat such high-risk patients with either adjuvant high-dose IFN or to consider entrance into a clinical trial.

Chemotherapy as a single adjuvant modality has not been shown to be more beneficial than observation alone, and highdose IFN with chemotherapy confers no difference in relapse-free or overall survival between the single agent and combined therapy arms. Peginterferon, which prolongs the half-life of the drug, allowing it to be delivered weekly, has been tested in several adjuvant trials in resected melanoma. Only in patients whose lesions were detected at sentinel node biopsy was there an advantage in disease-free survival for peginterferon.

E. Therapy of metastases

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Melanomas and Other Cutaneous Malignancies

Melanomas and Other Cutaneous Malignancies

Ragini Kudchadkar

Jeffrey S. Weber

More than 1 million Americans were diagnosed with skin cancer in 2009, making it the most common malignancy in the United States and accounting for considerable morbidity. Melanoma accounted for approximately 68,720 cases and was responsible for an estimated 8650 deaths in 2009, which far surpasses the number of deaths due to all other skin malignancies combined. Melanoma continues to increase in incidence at a higher rate than any other cancer in the United States, except for non-small-cell lung cancer in women. Approximately 5890 cases of nonepithelial skin cancer cases were diagnosed in 2009. These less common tumors of the skin include Merkel cell cancer, Kaposi sarcoma (see Chapter 25), and mycosis fungoides (MF).