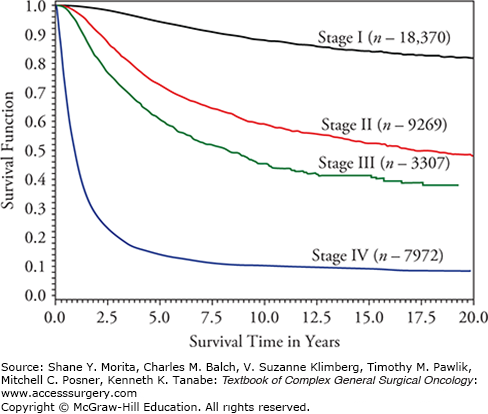

Revisions to the melanoma staging system were published in the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer manual (AJCC Cancer Staging Manual) in 2009 and were implemented in January 2010.1–3 The latest TNM criteria and stage groupings are shown in Tables 12-1 and 12-2, while survival rates according to disease stage are shown in Figure 12-1. In addition, we have published updated analyses on mitotic rate, as well as the prognostic significance of patient age and the sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), in determining accurate staging for clinically occult nodal metastases.4–7 This chapter incorporates material from the seventh edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual published in 2009, as well as a recent book chapter, along with the updated materials published since then.1,8

TNM Criteria for Cutaneous Melanoma (2010)a

| Melanoma TNM Classification | ||

|---|---|---|

| T Classification | Thickness | Ulceration/Mitoses Status |

| T1 | ≤1.0 mm |

|

| T2 | 1.01–2.0 mm |

|

| T3 | 2.01–4.0 mm |

|

| T4 | >4.0 mm |

|

| N Classification | # Metastatic Nodes | Nodal Metastatic Mass |

| N1 | 1 node | |

| N2 | 2–3 nodes | |

| N3 | 4 or more metastatic nodes, or matted nodes, or in transit met(s)/satellite(s) with metastatic node(s) | |

| N Classification | # Metastatic Nodes | Nodal Metastatic Mass |

| M Classification | Site | Serum LDH |

| M1a | Distant skin, subcutaneous tissue, or nodal metastasis | Normal |

| M1b | Lung metastases | Normal |

| M1c | All other visceral metastases | Normal |

| Any distant metastasis | Elevated | |

Anatomic Stage Groupings for Cutaneous Melanomaa

| Clinical Stagingb | Pathologic Stagingc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA | T1a | N0 | M0 | IA | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| IB | T1b | N0 | M0 | IB | T1b | N0 | M0 |

| T2a | N0 | M0 | T2a | N0 | M0 | ||

| IIA | T2b | N0 | M0 | IIA | T2b | N0 | M0 |

| T3a | N0 | M0 | T3a | N0 | M0 | ||

| IIB | T3b | N0 | M0 | IIB | T3b | N0 | M0 |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | T4a | N0 | M0 | ||

| IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 | IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 |

| III | Any T | N>N0 | M0 | IIIA | T1 – 4a | N1a | M0 |

| T1 – 4a | N2a | M0 | |||||

| IIIB | T1 – 4b | N1a | M0 | ||||

| T1 – 4b | N2a | M0 | |||||

| T1 – 4a | N1b | M0 | |||||

| T1 – 4a | N2b | M0 | |||||

| T1 – 4a | N2c | M0 | |||||

| IIIC | T1 – 4b | N1b | M0 | ||||

| T1 – 4b | N2b | M0 | |||||

| T1 – 4b | N2c | M0 | |||||

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |||||

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

There are five criteria that guide the selection of prognostic factors for inclusion in the melanoma staging system.9,10 First, the staging system must be practical, reproducible, and applicable to the diverse needs of all medical disciplines. Second, the criteria must accurately reflect the biology of melanoma based on consistent outcome results of patients treated at multiple institutions from multiple countries. Third, the criteria must be evidence-based and reflect the dominant prognostic factors consistently identified in Cox multivariate regression analyses. Fourth, the criteria must be relevant to current clinical practice and regularly incorporated in clinical trials. Fifth, the required data must be sufficiently easy for tumor registrars to identify in medical records to code staging information.

The recommendations for using tumor thickness when staging melanoma are unchanged with the seventh edition of the melanoma staging system that is in effect today.1 Ten-year survival is inversely related to increasing melanoma primary tumor thickness (92% T1, 80% T2, 63% T3, and 50% T4). Level of invasion is no longer a part of the current melanoma staging guidelines, especially for melanomas ≤1 mm in thickness. It has been replaced by the primary tumor mitotic rate described below. Primary tumor characteristics continue to guide the selection of excision margins and the use of regional lymph node staging procedures. Consensus guidelines recently published jointly by the Society of Surgical Oncology and the American Society for Clinical Oncology recommend that primary melanomas ≥1 mm in thickness, in the absence of clinically detectable regional nodal disease, should be offered a SLN staging procedure.11 The routine use of a SLN staging procedure for melanomas <1 mm in thickness cannot be supported by the current evidence. The consensus guidelines recommend, instead, that a SLNB procedure may be considered for individuals with high-risk primary melanomas (associated with ulceration and/or a mitotic index of ≥1/mm2) measuring <1 mm in thickness when the benefits of the procedure outweigh its risks.

Ulceration was recognized as the second most important prognostic factor after tumor thickness at the time of publication of the sixth edition of the melanoma staging system and remains an important component of the current seventh edition in effect today.12,13 It is histologically characterized by the absence of an intact epidermis overlying the primary melanoma. The incidence of ulceration is 6% for melanomas ≤1 mm in thickness and increases to 63% for melanomas >4 mm in thickness.14 When ulceration is present it identifies a locally advanced melanoma with a higher metastatic potential and is associated with worse survival relative to its nonulcerated counterpart.12,13,15,16 In fact, survival for ulcerated melanoma is nearly the same as that for nonulcerated melanoma of the next highest thickness category (Table 12-3).

Five Year Survival Rates Demonstrating the Importance of Upstaging in the Presence of an Ulcerated Primary Melanoma to Achieve Similar Outcomesa

| IA | IB | IIA | IIB | IIC | IIIA | IIIB | IIIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ulcerated | T1a | T2a | T3a | T4a | N1a, N2a | N1b, N2b | N3 | |

| 97% | 91% | 79% | 71% | 78% | 48% | 47% | ||

| Ulcerated | T1b | T2b | T3b | T4b | N1a, N2a | N1b, N2b, N3 | ||

| 94% | 82% | 68% | 53% | 55% | 38% |

The proliferation of cells within the primary melanoma is expressed by the mitotic rate and denoted as the number of mitoses per square millimeter. An elevated mitotic rate identifies a more rapidly growing melanoma with the potential for earlier metastases and worse survival than a tumor with little or no mitotic activity. The adverse effect of mitotic rate on melanoma survival was first described in 1953.17 More recently, mitotic rate has been identified as an independent prognostic factor in melanoma.4,18–29

Multivariate evaluation of the primary tumor mitotic rate using the AJCC melanoma database has shown this parameter to be an independent adverse predictor of survival (Table 12-4).1 Ten-year survival ranges from 97% for melanomas ≤0.5 mm in thickness and mitotic rate <1/mm2 to 28% for melanomas >6 mm in thickness and mitotic rate >10/mm2 (Table 12-5).4 It ranks second only to tumor thickness in predicting survival in the setting of localized melanoma (Table 12-4).4,30 When micrometastatic regional nodal disease from melanoma is present, mitotic rate ranks fourth after the number of metastatic lymph nodes, age, and ulceration in its ability to predict survival (Table 12-6).

Cox Regression Analysis for 10,233 Melanoma Patients with Localized Melanoma Including Mitotic Ratea

| Variable | Chi-square value (1 d.f.) | pValue | Hazard Rate | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor thickness | 84.6 | <0.0001 | 1.25 | 1.91–1.31 |

| Ulceration | 47.2 | <0.0001 | 1.56 | 1.38–1.78 |

| Clark’s Level | 8.2 | 0.0041 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.26 |

| Mitotic rate | 79.1 | <0.0001 | 1.26 | 1.20–1.32 |

| Site | 29.1 | <0.0001 | 1.38 | 1.23–1.54 |

| Gender | 32.4 | <0.0001 | 0.70 | 0.62–0.79 |

| Age | 40.8 | <0.0001 | 1.16 | 1.11–1.22 |

Ten-Year Survival Rate by Tumor Thickness and Mitotic Ratea

| Tumor Thickness (mm) | No. of Patients | Mitotic Rate (mitoses/mm2) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1.00/mm2 | 1.00–1.99/mm2 | 2.00–4.99/mm2 | 5.00–9.99 | 10.00–19.99 | ≥20.00 | Overall | |||||||||||||||

| % | SE | No. | % | SE | No. | % | SE | No. | % | SE | No. | % | SE | No. | % | SE | No. | % | SE | ||

| 0–0.50 | 1,521 | 97.1 | 0.9 | 1,194 | 97.1 | 1.7 | 207 | 93.2 | 3.9 | 89 | 87.7 | 8.6 | 27 | 4b | 0b | 96.7 | 0.8 | ||||

| 0.51–1.0 | 3,340 | 92.5 | 1.1 | 1,472 | 87.4 | 1.8 | 895 | 86.4 | 2.0 | 775 | 82.2 | 4.6 | 161 | 36b | 1b | 89.3 | 0.8 | ||||

| 1.01–2.0 | 3,367 | 90.9 | 1.8 | 488 | 83.1 | 2.2 | 703 | 79.4 | 1.7 | 1,351 | 76.5 | 2.6 | 577 | 70.1 | 4.7 | 205 | 73.8 | 8.7 | 43 | 80.9 | 1.0 |

| 2.01–3.0 | 1,520 | 77.2 | 6.6 | 78 | 75.8 | 4.2 | 188 | 65.3 | 3.0 | 555 | 70.8 | 3.1 | 397 | 58.2 | 4.6 | 241 | 47.7 | 9.8 | 61 | 67.0 | 1.7 |

| 3.01–6.0 | 1,459 | 78.8 | 8.2 | 58 | 56.7 | 7.8 | 100 | 57.1 | 4.0 | 381 | 58.5 | 3.2 | 477 | 55.2 | 3.8 | 333 | 34.3 | 8.7 | 110 | 56.8 | 1.9 |

| >6.00 | 414 | 11b | 18b | 53.0 | 8.7 | 89 | 52.6 | 6.0 | 135 | 28.1 | 7.6 | 119 | 42b | 48.0 | 3.8 | ||||||

AJCC 2008 Collaborative Melanoma Database—Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis (survival) for Stage III Melanoma with Mitotic Rate (1338 patients)a,b

| Variable | All Patients with Stage III (n= 1338)b | Patients with Micrometastasis (n= 1070)b | Patients with Macrometastasis (n= 268)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of positive nodes | 27.4 | 27.8 | 5.0 |

| Tumor burden (micro vs. macro) | 4.7 | — | — |

| Tumor thickness | 9.1 | 9.4 | 1.1 |

| Ulceration | 17.5 | 13.5 | 2.1 |

| Clark’s level | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Primary tumor mitotic rate | 4.4 | 12.7 | 0.2 |

| Age | 24.8 | 15.8 | 7.1 |

| Site | 4.3 | 4.7 | 0.4 |

| Gender | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

Mitotic rate is a continuous variable and no lower threshold could be identified in the AJCC melanoma database to serve as a predictor for survival. Patient prognosis was worse in the presence of any elevation of the mitotic activity (≥1/mm2) than if none was detected. Therefore, a mitotic rate of ≥1/mm2 was selected to identify primary melanomas with an increased metastatic risk. When this prognostic factor was examined for T1 melanomas, it was found to be the most powerful predictor of survival.1 When ulceration and mitotic rate were both included in this analysis, Clark’s level was no longer a statistically significant predictor of survival. Based on these results, the AJCC has required mitotic rate to be a part of the histologic assessment of the primary melanoma and incorporated this into the current staging system. In addition to the presence of primary tumor ulceration, an elevated mitotic rate is also used to identify the higher risk subset of T1 melanomas that may be considered for a SLNB procedure.

Satellite lesions, previously included in the T category, were grouped with in-transit lesions in the N category as stage III disease with the issuance of the sixth edition of the melanoma staging system. The seventh edition continues to retain this staging convention. A study from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center demonstrated that the distinction of satellite versus in-transit lesions based on the distance from the primary tumor had no prognostic significance, since both represented intralymphatic dissemination of melanoma.31 Survival is nearly the same for individuals with satellite, in-transit, and lymph node metastases, supporting the proposal that these should be grouped as stage III disease.32–42 When satellite/in-transit and lymph node disease are present concurrently, the survival for this group is worse than that when intralymphatic disease is present in the absence of regional nodal metastases (28% to 35% vs. 41% to 56%, respectively). The melanoma staging committee therefore recommended that, whenever possible, the status of the regional lymph nodes should be included in the staging system in the presence of satellite/in-transit disease.

Patient age has been reported as an independent prognostic factor in melanoma studies spanning over three decades.2,4,14,43–54 We have previously reported that patient age is a highly significant and powerful predictor of survival using the AJCC melanoma staging database, even after accounting for adverse prognostic features, such as the anatomic site of the primary melanoma and the patient’s gender.2,6,7,43

Yet, patient age has not been incorporated into staging systems and is not used consistently as a stratification criterion in early-stage melanoma clinical trials. There could be several reasons for this, especially among the older melanoma population. First, there is no reported threshold of patient age that clearly signals a worse prognosis. Second, it is unknown whether age reflects a crude surrogate of declining immune competence, or other co-morbidities, or differences in the biological behavior of melanoma in patients of different age groups. Third, patient age might not be a truly independent predictive factor, but instead may secondarily reflect a combination of adverse characteristics that cannot be accounted for in smaller patient series. Melanoma among teenagers and children is much less common, and as a consequence, few series report on a sufficiently large population to make a valid comparison with prognosis and demographics of melanoma patients <20 years of age with older melanoma population.

With increasing age by decade, primary melanomas were thicker, exhibited higher mitotic rates, and were more likely to be ulcerated. In a multivariate analysis of patients with localized melanoma, thickness and ulceration were highly significant predictors of outcome at all decades of life (except for patients less than 20 years). Mitotic rate was significantly predictive in all age groups except patients <20 years and >80 years. For patients with stage III melanoma, there were four independent variables associated with patient survival: number of nodal metastases, patient age, ulceration, and mitotic rate.

Patients under 20 years of age had primary tumors with slightly more aggressive features, a higher incidence of SLN metastasis, but, paradoxically, more favorable survival than all other age groups. In contrast, patients >70 years old had primary melanomas with the most aggressive prognostic features, were more likely to be head and neck primaries, and were associated with a higher mortality rate than the other age groups. Surprisingly, however, these patients had a lower rate of SLN metastasis per T stage. Among patients between the two age extremes, clinicopathologic features and survival tended to be more homogeneous. Thus, melanomas in patients at the extremes of age have a distinct natural history.

Several series have evaluated melanoma prognosis relative to the clinical and/or pathologic dimensions of nodal disease.14,32,36,55–58 Multivariate analysis of the data from these studies showed that size was not a significant prognostic factor. The most powerful prognostic factor was the number of positive lymph nodes (Fig. 12-2).35,36,56,59–61 Five-year survival decreased with increasing number of involved lymph nodes with the best grouping defined by the cutoffs of 1 versus 2–3 versus ≥4 nodes.38,45,62–64

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree