Three histologic variants of melanoma are reported within the HN region and are outlined below. It is important to realize that melanoma subtype does not generally influence prognosis once tumor thickness and other prognostic variables such as ulceration are taken into account. For this reason, the melanoma subtype does not impact tumor staging.

Common HN Melanoma Subtypes

The majority of HN cutaneous melanomas are

superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), accounting for ˜70% of all cases.

19 The characteristic SSM feature is color variation, which is often described as kaleidoscopic with areas of black, dark brown, tan, and blue-gray pigmentation. Areas of pink and white may be present and represent hypopigmentation secondary to tumor regression. Although SSM lesions are well circumscribed, the borders tend to be scalloped and asymmetric. Patients are usually diagnosed within their fourth to fifth decade and often report a preexisting nevus in the region of their newly diagnosed melanoma.

Nodular melanoma (NM) is the second most common melanoma variant, accounting for 15% to 30% of cases.

19 The majority of mucosal melanomas are of the nodular variant. The lesion typically appears as a raised, blue-black or blue-red nodule. As hemangioma, blue nevus, pyogenic granuloma, and pigmented BCC can appear similarly, it is important to biopsy lesions with this appearance before treating them to avoid undertreatment.

As mentioned above,

LM represents intraepidermal or melanoma in situ. Also known as “Hutchinson melanotic freckle,” it is often diagnosed in the background of chronic solar damage. The invasive counterpart to LM is

lentigo malignant melanoma (LMM). The exact percentage of LMs that progress to invasive LMM remains unknown.

50 It is speculated that if LM patients live long enough, all will progress to invasive melanoma. LM/LMM is commonly found within the H&N region. The subtype has been associated with older individuals, but the frequency in younger patients is increasing.

30 LM/LMM can display subepithelial extension as well as peripheral involvement with atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia (AJMH). These findings make achieving adequate surgical margins challenging from both an esthetic and a functional standpoint. Additional challenges associated with LMM are that both amelanotic and desmoplastic melanoma (DM) commonly arise in the setting of LM/LMM.

Desmoplastic Melanoma

DM is a rare subtype of melanoma composed of spindle cells with abundant collagen.

51 Although DMs are rare, accounting for only 1% of melanoma cases,

52 75% are diagnosed in the HN region. They commonly arise in the setting of LMM. DMs are distinct from other melanoma subtypes in that they present in an older patient population; the median age of diagnosis is 61 years compared to 46 years.

52 Although amelanotic cases account for only 7% of cutaneous melanomas, up to 73% of DM and DNM have been found to be amelanotic.

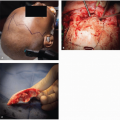

52,53 This atypical appearance

(Fig. 9.3), coupled with the spindle cell histology, makes DM somewhat of a diagnostic challenge. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is helpful because the majority of tumors will stain positive for S100 and vimentin; HMB-45 is less reliable due to the amelanotic appearance. DM is highly infiltrative, has a propensity for neurotropic spread, and is considered locally aggressive. Spread along cranial nerves to the skull base and cavernous sinus is not uncommon. In addition, early local recurrences are reported as high as 49%, and this may be related to undetected perineural spread.

53Primary treatment for DM remains surgical excision, with a minimum of 1 cm margins in order to prevent local recurrence. Pure DMs carry a low (<10%) rate of regional metastasis; therefore, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is not recommended in this setting.

54 Despite the low rate of regional metastasis, patients with this diagnosis have a similar risk for the development of distant metastases as patients with NM of similar depth of invasion. More commonly, melanomas will be classified as “mixed” DM. These lesions carry the same rate of regional metastasis as do other melanoma subtypes, and SLNB should be offered to patients meeting the criteria outlined in

Table 9.2. Evaluation of these lesions by an experienced dermatopathologist is critical in discerning between pure DM and mixed DM lesions.

Mucosal Melanoma

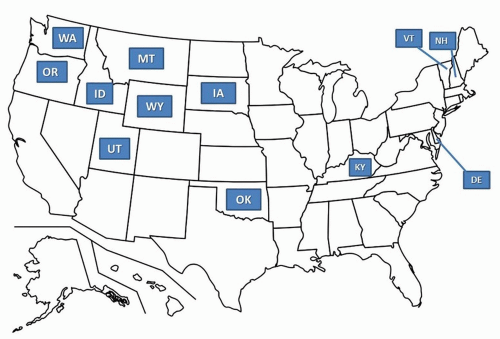

Mucosal melanoma (MM) represents a rare variant of melanoma, accounting for <2% of all cases.

55 Review of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 1987 to 2009 identified an increasing incidence of MM in the United States.

56 This increase was unique to the nasal cavity subsite, especially for women ages 55 to 84.

MM is regarded as a distinct and separate entity from its cutaneous counterpart. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, etiologic environmental factors have not been linked to the development of MM.

57 MM presents on average one decade later than cutaneous lesions.

58 In addition, women are diagnosed twice as often as men. Lastly, the BRAF oncogene mutation commonly identified in cutaneous melanoma is rarely found in the mucosal subtype. Instead, a relatively high incidence of KIT mutations has been reported.

59The majority of MMs arise in the nasal cavity. The anterior nasal septum is involved most often (33%), followed by the lateral nasal wall (28%), turbinates (15%), and nasal vestibule (10%).

60 The paranasal sinuses are another common site of origin, with the maxillary sinus involved most often. Given these anatomic locations, it is not uncommon for patients with sinonasal MM to present with nasal obstruction and epistaxis. These symptoms often lead to early diagnosis, with 75% of sinonasal patients presenting with localized disease only.

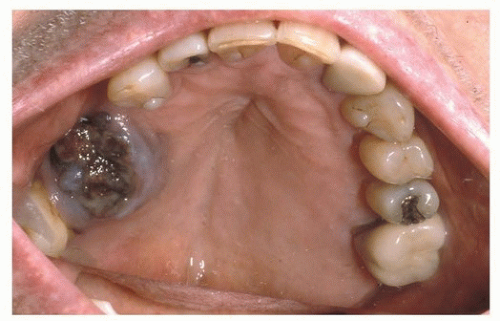

61Approximately 40% of HN MMs arise in the oral cavity (OC), with the upper alveolus and hard palate

(Fig. 9.4) reported as the most common subsite (70%).

62 OC MM is often asymptomatic and can go undiagnosed until a neck mass develops from metastasis.

63 A review of five major MM series by Batsakis et al.

64 found laryngeal primary tumors to account for fewer than 4% of all cases. Within the larynx, the supraglottis was the most common site of origin.

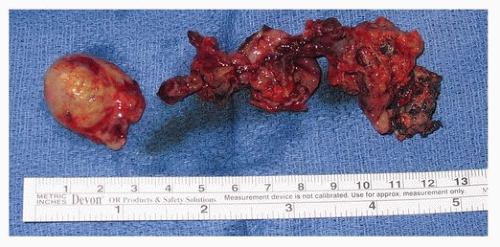

MM arises from respiratory stromal and mucosal melanocytes.

60 The diagnosis can be more challenging than that of cutaneous melanoma due to amelanotic nature of many tumors

(Fig. 9.5). For this reason, IHC plays an important role in diagnosis. MM will often stain for S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A (MART1). Olfactory neuroblastoma may stain for S100 and HMB-45; however, the MAP-2, cytokeratin, and epithelial membrane antigen stains will facilitate the correct diagnosis.

65 Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) will stain for cytokeratin but not S100 or HMB-45. Lastly, plasmacytoma and lymphoma are routinely leukocyte common antigen positive in the absence of S100 staining.

The recent 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging system now incorporates a dedicated tumor-node-metastases (TNM) staging system for MM.

66 The staging system begins with stage III disease because of the overall poor prognosis of MM, even in the setting of limited primary tumor burden. Due to the overall aggressive nature of MM, T1 and T2 categories do not exist. T3 tumors are limited to the mucosa. T4a represents moderately advanced disease with invasion into the deep soft tissue, cartilage, bone, or overlying skin. T4b is reserved for very advanced disease, which includes the brain, dura, skull base, cranial nerve, masticator space, carotid artery, prevertebral space, and mediastinal structures. Regional disease and distant disease also impact patient outcome. Patients with nodal metastasis are classified as N1, which upstages them to stage IVA. Similarly, patients with distant metastasis are designated M1 and are classified as stage IVC.

Wide local excision (WLE) of the primary tumor remains the standard of care, and therapeutic neck dissection is recommended for known nodal metastasis.

57 Elective management of the N-zero neck is based upon the site of origin. Sinonasal MM is usually confined to the primary site at presentation.

67 For this reason, an elective neck dissection (END) is not typically recommended. However, OC MM carries an increased risk for nodal metastasis and may warrant END.

Adjuvant radiation to the primary MM is recommended, regardless of depth of invasion. Extracapsular spread (ECS), two or more positive nodes, intraparotid nodal metastasis, any node >3 cm in diameter, and tumor recurrence are considered high-risk features warranting adjuvant radiation to the draining nodal basins.

57 Radiation planning is based on anatomic subsite and risk. The most common plan for high-risk MMs is conventional fractionation to 60 to 66 Gray (Gy) postoperatively or 70 Gy to gross disease.

Melanoma of the Auricle

Melanoma of the auricle was originally thought to carry a worse prognosis compared to other HN sites.

68 The increased risk was attributed to rich lymphatics, complex anatomic subdivisions of the auricle (6 hillock of His), and a paucity of subcutaneous tissue between the thin skin of the auricle and the underlying perichondrium.

69 For these reasons, total auriculectomy was historically considered standard of care. Retrospective reviews failed to demonstrate a difference in

local recurrence based on the extent of auricular excision.

69 After accounting for known prognostic features such as tumor thickness, recent studies demonstrate similar survival rates between melanoma of the auricle compared to other anatomic sites.

70 It is now recognized that current prognostic indicators and surgical principles can be applied safely to the auricular region. Perichondrium is considered a barrier to the spread of melanoma.

71 For this reason, the underlying cartilage requires resection only in the setting of tumor involvement or if previous surgery/biopsy has violated the plane making it impossible for the surgeon to determine if there was direct tumor extension.