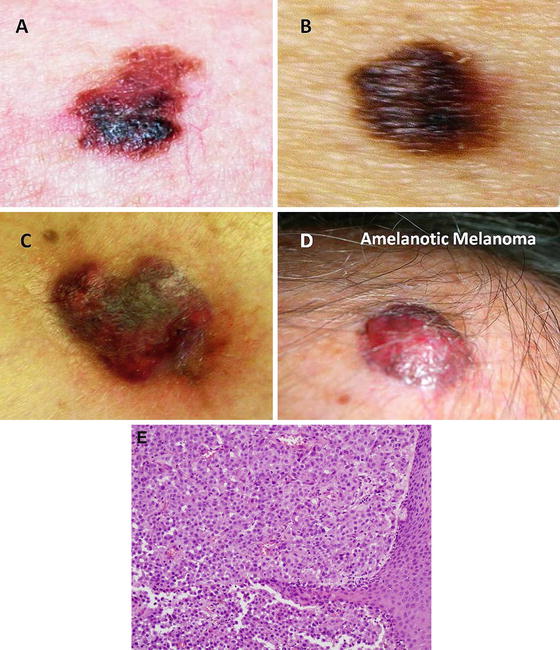

A: Asymmetry

B: Border (irregular)

C: Color changes

D: Diameter > 6 mm (size of a pencil eraser)

E: Evolving (any change in characteristics such as size, shape, color, elevation, new symptoms such as bleeding, itching, or ulcerating)

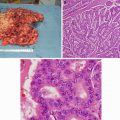

Fig. 1.1

(a–c) Melanoma and (d) amelanotic melanoma. (e) Photomicrograph showing sheets of neoplastic melanocytes deep to the epidermis with amphophilic cytoplasm, large ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Pigment deposition is relatively sparse in this example (hematoxylin and eosin X 200) (a–d: With kind permission from Ilene Rothman, M.D., Roswell Park Cancer Institute; e: Courtesy of Barry DeYoung, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine)

Fig. 1.2

Wide local excision of a melanoma. Note that the incision should be placed longitudinally along the long axis of the extremity. The length of the incision is generally 3× the width (Courtesy of Thuy-Tien Chu and Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

Useful immunohistochemical stainings include S100, HMB-45, MART-1/Melan-A, tyrosinase, and MITF [11].

Staging and Prognosis

The next step in management of a cancer patient is to accurately stage the disease. This allows appropriate treatment decisions to be made through risk-benefit analysis, often based on prognosis. Two scales are used to determine the depth of invasion: (1) Breslow’s thickness and (2) Clark’s levels (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3

Clark’s level: level 1, tumor confined to the epidermis; level II, tumor invades papillary dermis; level III, tumor fills the papillary dermis, but does not extend into the reticular dermis; level IV, tumor invades the reticular dermis; level V, tumor invades the deep subcutaneous tissue (Courtesy of Thuy-Tien Chu and Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

Melanomas are staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, where tumor depth (Breslow’s thickness), ulceration, nodal status, and metastases form the basis of prognosis (Table 1.2). Tumor depth is the strongest prognostic factor, whereas ulceration is the second most important prognostic indicator (Tables 1.3 and 1.4). Tumors with a Breslow’s thickness of less than 1 mm (1 mm ≈ width of a dime) are known as “thin” melanomas, whereas those between 1 and 4 mm are “intermediate thickness” and those greater than 4 mm (4 mm ≈ width of two nickels) are “thick.” Tumor depth forms the basis of the margin needed for excision and is also predictive of node positivity. For tumors ≤ 1 mm, 4 % have positive regional lymph nodes; 1.01–2.00 mm, 12 %; 2.01–4.00 mm, 28 %; and >4.00 mm, 44 % [12]. The relationship between depth and the risk of lymph node metastasis forms the basis for recommendations regarding surgical nodal staging.

Table 1.2

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for cutaneous melanoma (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed (e.g., curettage or severely regressed melanoma |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Melanoma in situ |

T1 | Melanomas ≤ 1.0 mm |

T2 | Melanomas 1.01–2.0 mm |

T3 | Melanomas 2.01–4.0 mm |

T4 | Melanomas > 4.0 mm |

Note: a and b subcategories of T are assigned based on ulceration and number of mitoses per mm2, as shown below | |

T classification | Thickness (mm) | Ulceration status/Mitoses |

|---|---|---|

T1 | ≤1.0 | a: w/o ulceration and mitosis <1/mm2 |

b: with ulceration or mitoses ≥1/mm2 | ||

T2 | 1.01–2.0 | a: w/o ulceration |

b: with ulceration | ||

T3 | 2.01–4.0 | a: w/o ulceration |

b: with ulceration | ||

T4 | >4.0 | a: w/o ulceration |

b: with ulceration |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

NX | Patients in whom the regional nodes cannot be assessed (e.g., previously removed for another reason) |

N0 | No regional metastases detected |

N1-3 | Regional metastases based upon the # metastatic nodes and presence or absence of intralymphatic metastases (in-transit or satellite metastases) |

Note: N1–3 and a–c subcategories assigned as shown below | |

N classification | # of metastatic nodes | Nodal metastatic mass |

|---|---|---|

N1 | 1 node | a: micrometastasis1 |

b: macrometastasis2 | ||

N2 | 2–3 nodes | a: micrometastasis1 |

b: macrometastasis2 | ||

c: in-transit met(s)/satellite(s) without metastatic nodes | ||

N3 | 4 or more metastatic nodes, or matted nodes or in transit met(s)/satellite(s) |

Distant metastasis (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No detectable evidence of distant metastases |

M1a | Metastases to skin, subcutaneous, or distant lymph nodes |

M1b | Metastases to lung |

M1c | Metastases to all other visceral sites or distant metastases to any site combined site combined with an elevated serum LDH |

Note: Serum LDH is incorporated into the M category as shown below | |

M classification | ||

|---|---|---|

Site | Serum LDH | |

M1a | Distant skin, subcutaneous, or nodal mets | Normal |

M1b | Lung metastases | Normal |

M1c | All other visceral metastases, Any Distant metastasis | Normal elevated |

Clinical staging3 | Pathologic staging4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Stage | Tis | N0 | M0 | 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | |

Stage 1A | T1b | N0 | M0 | I A | T1a | N0 | M0 | |

Stage 1B | T1b | N0 | M0 | I B | T1b | N0 | M0 | |

T2a | N0 | M0 | T2a | N0 | M0 | |||

Stage IIA | T2b | N0 | M0 | II A | T2b | N0 | M0 | |

T3a | N0 | M0 | T3a | N0 | M0 | |||

Stage IIB | T3b | N0 | M0 | II B | T3b | N0 | M0 | |

T4a | N0 | M0 | T4a | N0 | M0 | |||

Stage IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 | II C | T4b | N0 | M0 | |

Stage III | Any T | ≥N1 | M0 | III A | T 1–4a | N1a | M0 | |

T 1–4a | N2a | M0 | ||||||

III B | T 1–4b | N1a | M0 | |||||

T 1–4b | N2a | M0 | ||||||

T 1–4a | N1b | M0 | ||||||

T 1–4a | N2b | M0 | ||||||

T 1–4a | N2c | M0 | ||||||

III C | T 1–4b | N1b | M0 | |||||

T 1–4b | N2b | M0 | ||||||

T 1–4b | N2c | M0 | ||||||

Any T | N3 | M0 | ||||||

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | |

1Micrometastases are diagnosed after sentinel lymph node biopsy and completion lymphadenectomy (if performed) | ||||||||

2Macrometastases are defined as clinically detectable nodal metastases confirmed by therapeutic lymphadenectomy or when nodal metastasis exhibits gross extracapsular extension | ||||||||

3Clinical staging includes microstaging of the primary melanoma and clinical/radiologic evaluation for metastases. By convention, it should be used after complete excision of the primary melanoma with clinical assessment for regional and distant metastases | ||||||||

4Pathologic staging includes microstaging of the primary melanoma and pathologic information about the regional lymph nodes after partial or complete lymphadenectomy. Pathologic stage 0 or stage IA patients are the exception; they do not require pathologic evaluation of their lymph nodes | ||||||||

Table 1.3

Impact of tumor thickness and ulceration on survival in melanoma

Tumor thickness (mm) | 5 years survival: no ulcer (%) | 5 years survival: ulcer (%) |

|---|---|---|

≤1 | 95 | 91 |

1.01–2.00 | 89 | 77 |

2.01–4.00 | 79 | 63 |

>4 | 67 | 45 |

Table 1.4

Prognostic factors for cutaneous melanoma

Breslow’s thickness |

Ulceration |

Age |

Gender |

Anatomic location |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

Mitotic index |

Radial versus vertical phase of tumor growth |

Lymphovascular invasion |

Microsatellites |

Regression |

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

The incidence of ulceration is also greater with thicker tumor depth and is present in 6–12.5 % of thin melanomas versus 63–72.5 % in thick (>4 mm) melanomas. Ulceration decreases survival in all tumor thickness categories and is the only primary tumor factor that impacts prognosis of patients who have node-positive disease [13].

Other prognostic factors include age, gender, and anatomic location [13–15]. In a recent analysis , female gender was prognostically favorable, as 10-year survival rate for women was 86 % compared to 68 % for men [14]. Locations that were associated with higher risk of death included the back, back of upper arms, neck, and scalp (BANS).

Mitotic rate, which is measured as the number of mitoses per square millimeter, has also been shown to be an important independent prognostic factor [16–18]. For patients with stage I melanoma, the adjusted odds ratio of survival for patients with a mitotic rate of 0 was 12 times higher than that of patients with a mitotic rate of > 6/mm2 [17].

Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level is one of the patient factors most predictive of decreased survival. LDH remains predictive even after accounting for site and number of metastatic lesions. In stage IV melanoma, LDH level has a 79 % sensitivity and 92 % specificity in detecting disease progression [15]. LDH has been recommended by certain practice guidelines as part of surveillance for patients with melanoma.

Clinical nodal staging is an important part of the physical examination of patients with a diagnosis of melanoma. Whereas microscopic disease is clinically occult and only found on microscopic examination of excised lymph nodes, macroscopic disease is clinically or radiographically apparent. Survival rates between microscopically positive disease and macroscopically positive disease differ significantly. Balch et al. (2001) demonstrated a survival difference of 63 % for a single microscopic positive node versus 47 % for a single macroscopic positive node (p < 0.001) [15].

Clinical suspicion and understanding of prognosis may also dictate a metastatic workup be performed prior to surgical resection and sentinel lymph node biopsy. The National Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCCN) guidelines state that fine-needle aspiration biopsy of any clinically positive nodal disease, in-transit disease, or metastatic disease be performed prior to resection of the primary lesion. Furthermore, a metastatic workup can be considered if clinical suspicion is present in stage IB or stage II disease or without clinical suspicion in clinical stages III or IV disease [19]. Many forms of metastatic workup exist, and there is disagreement as to which is preferred. Chest x-ray, CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, and PET/CT with or without brain MRI are all used for metastatic workup and surveillance. The authors favor PET/CT with brain MRI for all deep (>4 mm) lesions, for patients with constitutional symptoms, and for those who are a high surgical risk due to comorbid conditions, although there is no one practice considered standard.

Treatment Principles

Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with locoregional melanoma, and survival for those with localized disease is greater than 98 % [1]. Locoregional control is achieved through a combination of wide local excision, sentinel node biopsy, completion lymphadenectomy, and adjuvant radiation. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy are reserved for high-risk, metastatic, or recurrent disease. There is no role for chemotherapy in the adjuvant treatment of melanoma. The most appropriate treatments for melanoma have been demonstrated through prospective randomized controlled clinical trials, many of them multi-institutional.

Treatment Specifics

Margins

Thin Melanoma

The appropriate margin needed for local control in melanomas of varying depths was long a source of debate, and historically margins were treated with massive local excisions, typically 4 cm or greater. In 1991, the World Health Organization (WHO) Melanoma Program Study completed a prospective randomized controlled trial of patients who had primary melanomas <2 mm in thickness to excision with margins of either 1 cm or ≥3 cm. There was neither disease-free nor overall survival rate difference between the two groups at a mean follow-up of 90 months, although some recurrences were noted in those >1 mm in depth with a 1 cm margin. The authors concluded that thin melanomas (≤1 mm thick) were adequately treated with a 1 cm margin, and this became the gold standard resection margin for treatment of thin melanomas [20, 21] (Table 1.5).

Table 1.5

Recommended margins and indications for sentinel lymph node biopsy based on melanoma thickness

Tumor thickness | Recommended clinical margins (cm) | Sentinel lymph node biopsy? |

|---|---|---|

In situ | 0.5 | No |

≤1 mm | 1 | ±a |

1.01–2 mm | 1–2 | Yes |

2.01–4 mm | 2 | Yes |

>4 mm | 2 | Controversialb |

Intermediate-Thickness Melanoma

Similarly, the US Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial prospectively randomized patients with 1–4 mm thick melanomas to be treated with either 2 or 4 cm excision margins. Overall recurrence rates were not significantly different: 2/244 (0.8 %) in the 2 cm group compared to 4/242 (1.7 %) in the 4 cm group. There was no significant difference in overall 5-year survival (80 % vs. 84 %). Those patients who had a 4 cm resection margin had significantly greater treatment morbidity. A 2 cm margin became the standard for intermediate-thickness melanomas as it was found to be equivalent to a larger margin but decreased the need for skin grafting and decreased hospital length of stay [22].

As a follow-up, Thomas et al. in 2004 randomized 900 British patients with truncal or extremity melanomas ≥2 mm to either surgery with 1 cm or 3 cm excision margins. Median follow-up was 5 years. Locoregional recurrence was 26 % higher in the group with a 1 cm margin, and the difference in disease-free survival approached statistical significance (p = 0.06). The authors concluded that in a small number of patients, the melanoma cells that remain after excision with 1 cm margin will prove fatal. The use of 1 cm margins is thus avoided in patients with melanomas ≥ 2 mm, and the 2 cm margin remains standard of care except when not technically feasible [23] (Table 1.5).

Thick Melanoma

In 1998, Heaton et al. retrospectively reviewed 278 patients in an attempt to determine an adequate margin in patients with thick melanomas (Figs. 1.4 and 1.5). They found that nodal status, thickness, and ulceration were significantly associated with overall survival in patients with melanomas greater than 4 mm in thickness. However, when compared using multivariate analysis, neither local recurrence nor excisional margin (<2 cm vs. >2 cm) significantly affected disease-free or overall survival. It was concluded that a 2 cm margin was adequate for intermediate and thick melanomas [24].

Fig. 1.4

Advanced melanoma (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

Fig. 1.5

Advanced melanoma (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

A 1 cm margin for melanomas less than or equal to 1 mm and 2 cm for those greater than 1 mm remains the standard of care today (Table 1.5).

Regional Lymph Nodes

Sentinel Node Biopsy

Historically, melanoma was treated by performing a wide local excision and regional lymphadenectomy. Lymphadenectomy carries significant morbidity, namely, lymphedema in approximately 20–30 % of patients. Sentinel node biopsy was developed as a potential technique that would provide prognostic information and minimize the morbidity associated with traditional lymphadenectomy (Figs. 1.6 and 1.7). It was also postulated to improve the accuracy of nodal staging, by identifying the most likely (sentinel) node to which disease would spread.

Fig. 1.6

Sentinel lymph node mapping of a melanoma of the left foot using lymphoscintigraphy. Radiotracer used was Tc-99 m sulfur colloid (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

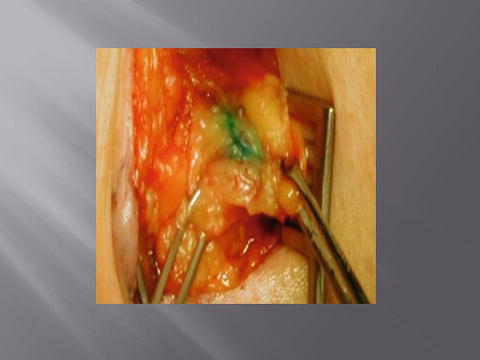

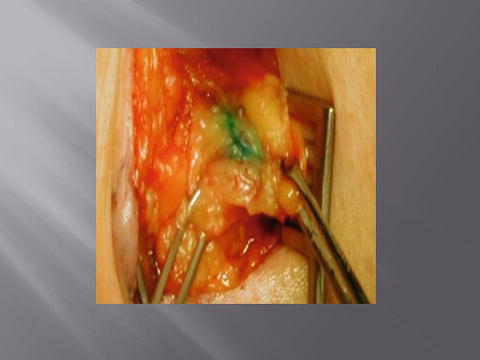

Fig. 1.7

Blue sentinel lymph node (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

In 1994, Dr. Morton and colleagues challenged the standard of immediate lymphadenectomy by applying the technique of sentinel lymphadenectomy to patients with melanoma. The Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1) [25] randomized 1269 patients with an intermediate-thickness primary melanoma to wide excision of melanoma and either observation of regional lymph nodes with lymphadenectomy if nodal relapse occurred or sentinel node biopsy with immediate completion lymphadenectomy if metastases were found in the sentinel node (Fig. 1.8). Among patients with a positive sentinel node, 5-year survival rates were higher among those who underwent immediate completion lymphadenectomy than among those in whom lymphadenectomy was delayed (72.3 ± 4.6 % vs. 52.4 ± 5.9 %; hazard ratio for death of 0.51; p = 0.004). It must be noted that although there was a survival difference within the subgroups of patients with nodal involvement, there was no significant difference in overall survival for the entire population. This was thought to be due to the dilution effect [26]. What this means is that because the rate of sentinel node metastasis was 16 %, the number of patients who could derive benefit from early lymph node dissection was diluted by the larger number of patients who had tumor-free nodes [26].

Fig. 1.8

Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT) design: Patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma underwent wide local excision and then randomized to either (1) observation or (2) sentinel lymph node biopsy. For those in the observation arm, a delayed node dissection is performed when the node(s) become clinically relevant; otherwise, patients continued to be observed. For those in the sentinel lymph node arm, a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy is observed, while a positive is subjected to a completion lymph node dissection. For those with nodal disease, immediate nodal dissection had better outcome (melanoma-specific survival) than those who had delayed nodal dissection. However, when comparing the two groups as a whole (red outlines), there was no overall survival benefit. This was thought to be due to the “dilution effect” (see text) (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

Due to its staging and prognostic value, this landmark trial established sentinel node biopsy as standard of care for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas (Breslow’s thickness, 1–4 mm). The technique was later established to be prognostically useful in patients with high-risk thin melanomas (Breslow’s thickness < 1 mm) where the node positivity rate is approximately 10 % [27] but remains controversial as to its utility in thick melanomas [28, 29]. High-risk thin melanomas are those that have evidence of ulceration or mitotic rate ≥ 1/mm2, especially in those with Breslow’s thickness 0.75–0.99 mm [29] (Table 1.5).

Completion Lymph Node Dissection

When a sentinel node biopsy demonstrates a lymph node metastasis, completion lymph node dissection is recommended. This remains the standard of care in the United States today [19], although it has become a controversial topic. Both sides of the debate agree that completion lymph node dissection has additional staging benefit, but randomized trials have not shown a survival benefit attributable to the procedure [30–33]. Furthermore, multiple trials have shown that only 18 % of patients will have disease within the remaining lymph nodes [25, 28]. An ongoing multicenter trial, the MSLT-II, aims to answer the question of completion lymph node dissection in patients with positive sentinel lymph node(s). Patients with positive sentinel node(s) will be randomized to either a completion lymph node dissection or observation with serial ultrasound of the nodal basin. Results are anxiously awaited, and until the clinical trial has been completed, patients should be recommended to have a completion lymph node dissection for positive sentinel node biopsy (Fig. 1.9).

Fig. 1.9

Groin lymph node dissection. The lymph node-bearing area is located within the femoral triangle, which is bounded by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the Sartorius muscle laterally, and the adductor longus muscle medially. The floor of the triangle is formed by the fascia over the adductor longus, iliopsoas, and pectineus muscles, while the roof is formed by the fascia lata. Exposed vessels are generally covered with the sartorius muscle, which can be detached at its origin and transferred medially as a flap without disrupting the neurovascular supply, which is located laterally. The muscle flap can be sutured to the inguinal ligament and/or adjacent tissue with 3–0 or 4–0 absorbable sutures (a: Courtesy of Thuy-Tien Chu and Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS; b–d: Reprinted from Ref. [76]. With permission from Elsevier)

Initial Lymphadenectomy

As mentioned above, clinically positive regional nodes portend a poor prognosis. The estimated 5-year overall survival (OS) rates range from 20 % to 40 % [34–36]. The NCCN guidelines recommend fine-needle aspiration biopsy to confirm the presence of metastases followed by immediate lymph node dissection at the time of initial operation [19]. Patients who are clinically node positive should be carefully staged to evaluate for systemic disease prior to surgical therapy. Whether patients should undergo a superficial groin dissection or a combined superficial and deep groin dissection remains controversial. There is no randomized trial that directly compares superficial groin dissection with combined superficial and deep groin dissection. In general, a superficial groin dissection is recommended for those with positive sentinel lymph node, while a combined superficial and deep groin dissection is reserved for those who have clinically gross involvement of the groin, clinically detectable deep lymph nodes, histologically positive Cloquet’s node (node medial to the femoral vein at the level of the inguinal ligament), or pelvic lymphadenopathy as seen on CT scans [35].

Surgery for Oligometastatic Stage IV Disease

Historically, patients with advanced melanoma (Figs. 1.10 and 1.11) have been offered surgery for palliation only, and the lack of efficacy of this approach has been reinforced by a stable rate of survival for advanced stage melanoma over the past 30 years. Median survival of patients with stage IV disease is less than 8 months in numerous studies. A subset of patients exists, however, where palliative resection may prove beneficial [37]. Patients with a disease-free interval of 3 years prior to developing stage IV disease have significantly better survival (p < 0.001) than those with shorter disease-free intervals [38]. When isolated and a few number of lesions, surgical excision can be safe and effective if patients are carefully selected. Excision should be performed before disease is bulky and symptomatic, and a margin greater than 1 cm minimizes local recurrence, although repeat excision is often needed. In these carefully selected patients, median survival is approximately 2 years [39].