Paul Stolee

Measuring Outcomes of Multidimensional Geriatric Assessment Programs

Although frailty in older adults may be associated with an underlying loss of complexity in many physiologic systems,1 the clinical conditions and geriatric syndromes2,3 that are commonly present in frail older adults are often highly complex. This clinical complexity, including the presence of multiple interacting medical and social concerns, is the challenge and also the joy of geriatrics.4,5

Geriatric services respond to this complexity with comprehensive approaches to assessment, multidisciplinary teams, and multidimensional interventions. Although there may be widespread agreement on the need for comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and multicomponent approaches, there is less agreement on the specific elements of these approaches. It is also not always clear which specific interventions or aspects of care (or combinations thereof) make a difference for an individual patient or for groups of patients—hence, the references to the black box of geriatrics.6,7 Clinical complexity and comorbidity have often meant that frail older adults are excluded from many clinical trials,8 although there have been recent efforts to rectify this.9–11 This exclusion is problematic in terms of the interventions being tested and results of the studies, which are not relevant or generalizable to many frail older adult patients.12,13 Multicomponent interventions have been found to be more effective than single-component interventions for frail older patients14 but these types of programs are much more difficult to evaluate in the context of clinical trials.12 Allore and colleagues15 have made a distinction between statistical and analytic considerations and clinical considerations in the design of such trials. Statistical or analytic considerations would suggest that one specific intervention should target a single outcome or risk factor, the basis on which power calculations are generally undertaken.8 Clinically, however, it makes sense for interventions to target more than one outcome or risk factor, and many interventions are likely to have overlapping effects.15 For studies of interventions for frail older patients, clinical and analytic considerations are particularly at odds.

Given the heterogeneity of the patient population and the heterogeneity of clinical interventions, it is not surprising that evidence for the effectiveness of geriatric interventions has been hard to establish. Rubenstein and Rubenstein16 have closely observed this literature over the years and have pointed out a number of factors associated with an increased likelihood of demonstrating their effectiveness. These include appropriate targeting, more intensive interventions, control over longer term management, and a usual care control group. To this list, it is suggested here that an additional consideration be added, the selection of meaningful and responsive outcome measures. The selection of appropriate outcome measures for geriatric interventions is not straightforward and has been identified as a priority for research.17,18 In the early 1990s, a working group of the American Geriatrics Society achieved a consensus on measures appropriate for measuring outcomes of geriatric evaluation and management units.19 The consensus statement recommended 12 physical outcomes, three psychological and social functioning outcomes, and 17 outcomes related to health care utilization and cost, reflecting concerns about future implementation and funding. The number and variety of these measures reflect the multidimensional nature of geriatric care as well as its potential system impact. Although all these measures may have relevance to specialized geriatric interventions, few, if any, of these measures would be relevant for all patients. The question therefore becomes how to achieve nonarbitrary dimensionality reduction from multidimensional interventions with multidimensional outcomes.

A more recent attempt to achieve a consensus on outcome measurement for older patients was undertaken by a U.S. National Institute on Aging (NIA) expert panel in 2001.20 This working group was charged to “recommend the content of a core set of well-validated universal patient-centered outcome measures that could be routinely measured and recorded widely in health care delivery”20 for older persons with multiple chronic conditions. This group recommended an initial composite measure, such as the SF-3621 or the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 29-item Health Profile (PROMIS-29)22 be used, with these results forming a basis for targeting additional follow-up measures. This approach has the potential to be more feasible in routine clinical practice, but still may require a fairly large array of outcome measures. The working group was unable to achieve consensus on appropriate follow-up measures in several important assessment domains, including disease burden, cognitive function, and caregiver burden. Also, despite an intention to recommend patient-centered measures, patients were not included in the consensus process nor were measures proposed to elicit patient preferences and values, which would be fundamental to a patient-centered approach.23

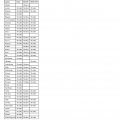

Some of the challenges associated with measuring outcomes of multidimensional geriatric interventions can be gauged by reviewing the outcome measures used in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of these interventions. Relevant studies were identified from selected major systematic reviews and meta-analyses, beginning with the seminal meta-analysis of comprehensive geriatric assessment services published by Stuck and associates in 1993.24 Other reviews included a review of studies specifically focused on outpatient geriatric assessment,25 two reviews of studies focused on preventive home visits,26,27 and one review that specifically targeted multicomponent interventions.15 Collectively, these reviews reported results from 56 RCTs (see Appendix Table 38-1). Outcome measures were categorized into mortality, self-rated health, health care utilization, three assessment domains (physical function, cognitive function, and psychosocial outcomes), and an “other” category. These 56 studies are summarized as follows (see Appendix Table 38-1):

This review illustrates several points. Geriatric services were associated with statistically significant benefits in each category of outcome measure in at least some studies, but no category of outcome was significantly improved in all studies. None of the studies reported significant improvement in all the outcomes measured. The review also highlights the range of outcomes considered meaningful and plausible for geriatric services. Mortality is a clear end point and amenable to summation and comparison in meta-analyses, but is not necessarily the most meaningful outcome for programs serving a frail clientele for whom life expectancy is limited.8 Indicators related to health care utilization are of great relevance to the health care system and, although they may relate to an older person’s quality of life (e.g., for some older adults their quality of life may be higher in a community setting than in a long-term care home), these are at best indirect measures of quality of life from a patient’s perspective. Within each of the other domains, there is further evidence of heterogeneity; each domain has multiple aspects, and a large variety of instruments and approaches have been used to measure these. Even within the “other” category, an outcome such as falls is itself a multifactorial syndrome.15

Geriatric Assessment Outcomes and Quality of Life Measures

The assessment domains commonly measured in geriatric intervention studies can be seen as major components of quality of life. If outcomes commonly targeted by multidimensional geriatric interventions can be considered, collectively, as a reflection of quality of life as the overarching domain of importance, a sufficiently comprehensive quality of life measure could be a good choice as an outcome measure for common use in geriatric intervention studies. A candidate measure is the SF-36,21 or one of its variants with subsets of items, which has been very widely used as a health-related measure of quality of life.28 Unfortunately, testing of its use with older adults has not been extensive,8 and results of these studies have suggested that the utility of this measure with older patients may be limited.29–32 A promising measure is the EQ-5D,33 which quantifies an individual’s health-related quality of life into a single index value and provides a descriptive profile. It has proven to be a valid, reliable, and easy to use measure.34–41 However, it has also been shown to have limitations—predominantly, ceiling effects and poor sensitivity at the top of the scale.36,37,39,42–44 A revised five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) has shown promise in addressing these limitations.45–47 A few studies have tested the EQ-5D in populations that include older subjects40,41,48,49; further work in this area would be welcome.

Despite some promising work in quality of life measurement, the development of any measure that could achieve wide acceptance has been hindered by the lack of a common conceptual or theoretical understanding of the meaning of quality of life and by lack of agreement on its constituent elements.50 Spitzer has argued that the development of a gold standard measure is possible, even for a subjective construct such as quality of life: “We fail to have a Gold Standard…because no one has made it his or her primary objective to develop a Gold Standard either for measures of health status or for measures of quality of life…I believe Marilyn Bergner and her co-workers have a sufficiently long head start that they deserve support from all the rest of us.”51 Although Spitzer pointed to the work of Bergner on the Sickness Impact Profile52 as the best candidate for further development as a gold standard quality of life measure, Bergner turned out not to share this view: “The bitter truth is that there is no gold standard, there is unlikely ever to be one, and it is unlikely to be desirable to have one.”53

Standardized Assessment Systems

Another approach that aims at providing a comprehensive assessment of health and social functioning is the use of a standardized assessment system, of which the interRAI minimum data set (RAI or MDS) assessment systems are the most prominent. The interRAI instruments are a comprehensive assessment and problem identification system developed by an international consortium of researchers.54 The original interRAI assessment was developed for long-term care homes (MDS 2.0) in response to U.S. government regulations (Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987) aimed at improving nursing home quality.55 The interRAI home care assessment instrument (RAI-HC or MDS-HC)56 has been developed for home care settings. Other versions have been developed for use in mental health, acute care, palliative care, and other settings.57–59 RAI assessment items include personal items, referral information, cognition, communication and hearing, vision, mood, behavior, physical functioning, continence, disease diagnoses, preventive health measures, nutrition status, oral health, skin condition, environmental assessment, and formal and informal service use. Specific scales have been derived from RAI assessment items, including measures of activities of daily living (ADLs), cognitive impairment, depression, and pain.60–63 Application of the RAI system has been linked with reduced institutionalization and functional decline.64 The approach to data collection is one of best available information, which may be done by an interview or observation of the older adult via an interview of their caregiver (paid or unpaid) or through chart review. Although this approach may suggest the possibility of inconsistent data collection, it should be noted that there has been growing support for outcome measurement that incorporates a variety of perspectives, including self-report, proxy, and objective measures.8,65 Briefer screening tools have been developed as part of the RAI system, including the RAI contact assessment.66 When articulated with the more comprehensive RAI assessments such as the MDS 2.0 and the RAI-HC, the RAI system could thus be seen as an alternative strategy to achieve the aims of the NIA working group mentioned earlier20 (i.e., a screening tool followed by more in-depth assessment).

An important advantage of the interRAI system is that it allows for consistency in data collection across sites and across types of care settings; the various versions of the RAI instruments use similar questions and data collection approaches. This advantage is particularly strong when contrasted to the alternative practice of trying to achieve consensus on the battery of measures that should be used in clinical practice and outcome evaluation. Even if a particular group achieves consensus on a set of tools (e.g., as noted by Dickinson67), another group is likely to agree on a different set (e.g., as noted by Pepersack68), and it is unlikely that all members of either group will be consistent in their use of the prescribed measures.

A limitation of the interRAI assessment systems is the same as for other approaches aiming to achieve a comprehensive, multidimensional assessment; not all the assessment areas will point to relevant clinical outcomes for all patients, and it would still be necessary to identify the specific outcomes of interest for a specific intervention or for a specific patient. In the interRAI system, this is addressed to some extent through the use of triggers used to identify issues warranting further investigation, referred to as resident assessment protocols (RAPs)69 or clinical assessment protocols (CAPs).70

Individualized Outcome Assessment and Patient-Centered Care

The inadequacies of outcome measures have often been suggested as a possible explanation for negative or ambiguous results of intervention trials. This is illustrated in the following comments from several studies:

• “The fact that we observed no significant differences in the prevention of decline in activities of daily living or cognitive function in our study may be explained in several ways … (including) … insensitivity of our outcome measures to improvements that did occur.”71

• “There might, however, have been positive effects which we could not detect. Our measurements on the health state may not have been sensitive enough to show relevant effects.”72

• “The outcome variables may have been wrongly chosen to measure the effects of this kind of program.”73

• “Common measures of disability may be insensitive to change in the outpatient setting of the day hospital.”74

• “For most of the published programs, efficacy was tested on questionable indicators (e.g., mortality, health services use), on a crude proxy for functional decline (e.g., admission to a nursing home) or using a global unresponsive measure of functional autonomy.”75

• “It is possible that the measures we used to evaluate health-related quality of life lacked sufficient sensitivity.”76

A point made clear in Appendix Table 38-1 is the lack of consensus and consistency in the selection of outcome measures for geriatric interventions. The heterogeneous and individualized nature of geriatric programs and their patients makes such a consensus unlikely. Williams77 has argued strongly for the individualized nature of geriatric care:

It is clear, first, that there are immense individual differences among older people, more than at any earlier age, in virtually all types of characteristics—physical, mental, health, socioeconomic. Thus when we consider what quality of life means to an older person and what features of quality of care may contribute to that quality of life, we must arrive at highly individualized conclusions. This principle is of course recommended for all ages, but it may not be so essential in some aspects of earlier life as it is in the lives of older people.

One attempt to reflect the individualized nature of older adults in outcome measurement is the use of clinical judgment, with such measures as the Clinical Global Impression78 or Clinician Interview-Based Impression.79 These approaches allow a clinically experienced rater to reflect individual characteristics and health concerns in an overall assessment of improvement. They provide a role for informed clinical judgment in outcome assessment, but do not provide details on the specific aspects of a patient’s health or quality of life that may have been improved as the result of an intervention.

The individualized nature of geriatric care can also be addressed through individualized outcome measures. These could also be used to reflect individual patient preference, goals, and values in a manner consistent with a patient-centered care approach.80 Individualized outcome measures allow for specific measurement domains to be selected that are most relevant for individual patients. Individualized measures can be used to generate clinical insights into the nature of the effects of geriatric interventions, and particularly into understanding the effects of Alzheimer disease treatment81:

To the extent that standard measures do not record ways in which important improvements or deteriorations occur, they miss an opportunity to enhance our understanding of what Alzheimer’s disease looks like when it gets better, and to provide clinical correlates of supposed pharmacologic changes. In this regard, I believe that the developments of individualized outcome measures may provide some useful insights into patterns of clinically important changes and heterogeneous disease conditions.82

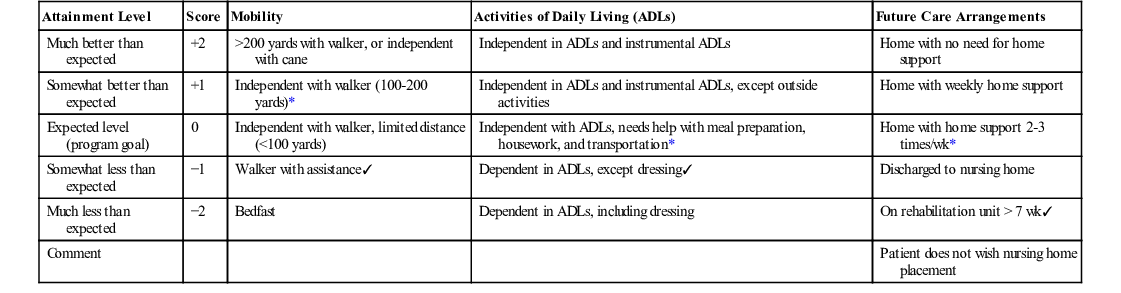

A number of fully or semi-individualized measures have been developed for use in a variety of settings.83 The most widely known of these is likely Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), which was proposed by Kiresuk and Sherman in the 1960s as a tool for evaluating human service and mental health programs.84 GAS is an individualized goal setting and measurement approach that enables users to individualize goals to the needs, concerns, and wishes of a specific patient and to individualize the scale on which attainment of these goals is measured. GAS accommodates multiple individualized goals and also permits calculation of an overall score that enables comparisons among individuals or groups of patients. GAS differs from other individualized measures in two important respects. First, GAS allows for the individualization of the scales on which goals are measured, as well as the goals. Second, GAS requires a judgment to be made at the beginning of treatment on the level of goal attainment that will be considered to be a successful outcome—rather than, for example, subjectively rating achievement of outcome on 10-point scales, as in the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure.85

Individual goals are scaled on a five-point rating scale of expected outcomes: −2, much less than expected; −1, somewhat less than expected; 0, expected level (program goal); +1, somewhat better than expected; and +2, much better than expected. The steps to construct a GAS follow-up guide are detailed in Box 38-1. An example follow-up guide is provided in Table 38-1. Goals can be weighted in terms of their relative importance, although equally weighted goals are generally recommended.86 A summary goal attainment score (T score) allows comparison of outcomes for different patients or for groups of patients. GAS scores for a large group of patients are expected to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The GAS score can be calculated using a formula84 or looked up in a table (e.g., see Zaza and coworkers’ study87) if goals are unweighted. A standardized menu approach has been proposed as a means to facilitate goal setting.88

TABLE 38-1

Goal Attainment Scaling Follow-Up Guide

| Attainment Level | Score | Mobility | Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) | Future Care Arrangements |

| Much better than expected | +2 | >200 yards with walker, or independent with cane | Independent in ADLs and instrumental ADLs | Home with no need for home support |

| Somewhat better than expected | +1 | Independent with walker (100-200 yards)* | Independent in ADLs and instrumental ADLs, except outside activities | Home with weekly home support |

| Expected level (program goal) | 0 | Independent with walker, limited distance (<100 yards) | Independent with ADLs, needs help with meal preparation, housework, and transportation* | Home with home support 2-3 times/wk* |

| Somewhat less than expected | −1 | Walker with assistance✓ | Dependent in ADLs, except dressing✓ | Discharged to nursing home |

| Much less than expected | −2 | Bedfast | Dependent in ADLs, including dressing | On rehabilitation unit > 7 wk✓ |

| Comment | Patient does not wish nursing home placement |

The first published use of GAS in geriatrics was in 1992.89 Since then, the measurement properties of GAS in geriatric settings have been tested in a number of studies.90 GAS has been found to have good interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.87 to 0.9389,91,92) and to correlate with standardized measures such as the Barthel index and with global ratings.92 Of particular significance for outcome measurement in geriatrics is that GAS has consistently been found to be very responsive to change. This has been demonstrated in before and after studies, including a multisite study and in the context of a randomized controlled trial.91–96 GAS has been used as an outcome measure in randomized trials of a geriatric assessment team and an antidementia medication.97–99 In both cases, GAS measured statistically significant benefits of the intervention. The clinical utility of GAS in geriatrics has been assessed using qualitative methods.100

GAS is a measure that seems to be a particularly strong fit for the measurement needs and constraints of multidimensional geriatric interventions. It has potential as a research measure and a clinical tool. Although goal priorities may differ among patients, caregivers, and clinicians,101,102 involving diverse perspectives can generate rich insights into the interventions that will most benefit older patients and into the effects of these interventions.

Reuben and Tinetti have recently recommended that a goal-oriented approach, such as GAS, be used for patient-centered outcome measurement.80 They argued that such an approach facilitates decision making for patients with multiple conditions and aligns decision making with individual goals rather than universally desired health outcomes. This position can be contrasted with the aim of the NIA working group to achieve a set of universally applied measures.20

In addition to the measurement of individual health outcomes, patient-centered care approaches are increasingly concerned with active engagement of patients in their care and with the measurement and understanding of patients’ experiences of care.103–105 Measurement of patient experience can yield insights that are valuable in identifying priorities for quality improvement.106 Older patients and their families often feel disengaged in their care, and greater understanding and measurement of their experiences may lead to improved quality and outcomes of geriatric services.107–109

Conclusion

Measuring the outcomes of multidimensional geriatric interventions presents significant challenges. These challenges have resulted in frail older patients often being excluded from studies of interventions from which they might benefit and in potential benefits of geriatric interventions not being detected by the measures used. After 30 years of controlled trials in geriatrics, it seems unlikely or perhaps even inappropriate that consensus will be achieved on a set of standardized measures that will have wide applicability. Application of a universal set of outcome measures may also compromise efforts to achieve patient-centered care approaches that reflect individual patient preferences and needs. For multidimensional geriatric interventions, goal setting and outcome measurement thus need to balance the values of patient-centered care with the benefits of consistent data collection.

For consistency of data collection and to provide comprehensive assessment information, there is a strong rationale to move toward standardized health information systems, such as the interRAI. In measuring outcomes, GAS is an effective, clinically useful, and patient-centered approach to addressing the challenges of outcome measures for heterogeneous, frail older adults.

Appendix

APPENDIX TABLE 38-1

Randomized Controlled Trials of Geriatric Interventions and Associated Outcome Measures

| Study | Setting | Study Description (Duration, No. of Subjects) | Outcome Measures | ||||||

| Physical Function | Cognitive Function | Psychosocial | Self-Rated Health | Mortality | Health Care Utilization | Other | |||

| Allen et al, 19861 | IGCS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 185; evaluated whether a geriatric consultation service (GCS) can provide additional input into patient care and strategies that improve compliance to this input | Katz Index of activities of daily living,2 Older American’s Resources and Services (OARS), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) scale3 | Pfeiffer short portable mental status questionnaire4 | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)5 | Admitting service used, number of days in institution | Veterans Alcoholism Screening Test,6 time of yr of consultation, number of medical problems/patient, compliance rates of recommendation; direct discussion with house staff led to increased compliance in intervention group (P = .0030) | ||

| Alessi et al, 19977 | HAS (United States) | 3 yr, N = 202; measured the process of comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and determined: (1) major findings in CGA; (2) emergence of annual clinical yield of CGA; and (3) factors that affect patient adherence with recommendations | Oral health assessment,8 vision and hearing test,9 gait and balance assessment,10 functional status assessment,11 hematocrit and glucose testing, urinalysis, fecal occult blood testing | Kahn-Goldfarb mental status questionnaire12 | Social assessment, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)13 | Percentage of ideal body weight,14 medication review,15 environmental assessment, adherence to recommendations; subjects more likely to adhere to recommendations involving referral to a physician than a nonphysician professional, for community service, or for recommendations involving self-care activities (P < .001) | |||

| Applegate et al, 199016 | GEMU (United States) | 1 yr, N = 155; evaluated whether care for older patients in a geriatric assessment unit would affect their function, rate of institutionalization, and mortality | Self-reported ability to perform physical activities,17 performance on timed physical tests,18 self-reported ADLs showed significant improvement in study group than control in first 6 mo (P < .05) | Folstein Mini-Mental State examination (MMSE)19 | CES-D5 | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score20 | Control group patients at lower risk of immediate nursing home placement had significantly higher mortality at 6 mo (95% CI, 1.2 to 15.2; P < .05); was no significance in higher risk stratum | After 6 wk, significantly fewer study patients living in an institution (P < .01); no significance at 6 mo; significantly fewer study patients institutionalized at 1 yr (P < .05), risk of nursing home admission 3.3 times higher in control group (95% CI, 2.6 to 3.8; P < .001), study group spent more days in rehabilitation than control group (P < .0001) | |

| Beyth et al, 200021 | GEMU (United States) | 6 mo; N = 325; studied the effectiveness of multicomponent management program of warfarin therapy and warfarin-related major bleeding in older patients | Recurrent venous thromboembolism, therapeutic control of anticoagulant therapy measured by patient-time approach22 and INR23; intervention group within therapeutic range at each time period significantly more often than controls (P < .001) | No significant difference between groups | Bleeding Severity Index24 showed significantly more incidence of bleeding in control group at 1, 3, and 6 mo (P = .0498) | ||||

| Boult et al, 200125 | OAS (United States) | 18 mo, N = 568; studied the effectiveness and costs of geriatric evaluation management (GEM) in preventing disability | Bed disability days (BDDs), restricted activity days (RASs),26 sickness impact profile (SIP): physical functioning dimension27; treatment group lost less function after 12 and 18 mo (aOR = .67; 95% CI, 0.47-0.99), had fewer health-related restrictions in ADLs (aOR = .60; 95% CI = .37-.96) | GDS28; treatment group less depressed at 12 mo (P < .01) and 18 mo (P < .01) | Individual questions on general health29 | No significant difference | Costs, Medicare expenditure, individual questions on use of nursing home and home health services; treatment group used less home health services (aOR = .60; 95% CI, 0.37-0.92) | ||

| Burns et al, 200030 | OAS (United States) | 2 yr; N = 98; aimed at comparing the effectiveness of long-term primary care management by interdisciplinary geriatric team | Katz Index,2 instrumental ADL (IADL) deficits 31 significantly better in GEM group at 1 yr (P = .006),11 study subjects showed improvement in Rand general well-being inventory32 (P = .001) | Study group showed increase in MMSE19 at 2 yr (P = .025) | Study group showed improvement on perceived global social activity (GSA)33–35 (P = .001), on CES-D5 (P = .003), and on perceived global life satisfaction (GLS) scale33–35 (P < .001) at 2 yr | Study subjects showed improvement on global health perception33–35 (P = .001) at 2 yr | No significant difference | Number of days in institution, study subjects had smaller increases in number of clinical visits (P = .019) at 2 yr | |

| Carpenter et al, 199036 | HAS (United Kingdom) | 3 yr, N = 539; tested benefits of regular surveillance on older adults living at home | Winchester Disability Rating Scale36 | No significant difference | Geriatric and psychogeriatric community support services, primary health care team contacts, use of community support services, control group spent 33% more days in an institution than study group (P = .03) | Falls doubled in control group but remained unchanged in study group (P < 0.05) | |||

| Clarke et al, 199237 | HAS (United Kingdom) | 3 yr, N = 523; tested the effect of social intervention in terms of mortality and morbidity on older adults living alone | ADLs38 | Measure of cognitive impairment and simple screening tool for dementia39 | Wenger scale (measure of support networks),40 Wenger modification of the Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale,40,41 social contact score42 | Perceived health status significantly greater in treatment group† | No significant difference | ||

| Cohen et al, 200243 | GEMU/OAS (United States) | 3 yr, N = 1388; assessed the effects of inpatient units and outpatient clinics on survival and functional status | Survival and quality of life with Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form General Health Survey (MOS SF-36),44,45 Katz ADLs,2,46 physical performance test,47 positive effects on bodily pain at 12 mo in GEMU treatment group (P = .01)* | No significant difference | Use of health services, costs, GEMU treatment group experienced more days in hospital (P < .001) | ||||

| Counsell et al, 200048 | GEMU (United States) | 3 yr, N = 1531; tested whether multicomponent intervention, called Acute Care for Elders, improved functional outcomes and the process of care in hospitalized older patients | Mobility index,49 physical performance and mobility examination (PPME),50 Charlson comorbidity score,51 IADLs,31 Katz Index2 decline at 12 mo favored intervention group (P = .037); fewer intervention patients experienced composite outcome of ADL decline from baseline or nursing home placement at discharge (P = .027), persisted at 1-yr follow-up (P = .022) | Pfeiffer short portable mental status questionnaire4 | CES-D (short form),52 physicians more often recognized depression in intervention group than in controls (P = .02), patient satisfaction with hospitalization53 higher in intervention group (P = .001), along with caregiver satisfaction (P < .05) | Overall health status, APACHE II20 | Reason for hospitalization, time from admission to initiation of discharge planning, social work consultations, orders for bed rest, physical therapy consults, application of physical restraints, length of stay, costs, intervention; physicians significantly reported no difficulty getting treatment plans carried out (P = .010) and that they were often informed of useful information on discharge plans (P = .015); intervention nurses reported higher satisfaction with extent of care (P = .001) and extent to which issues were discussed (P = .001) | Medications | |

| Epstein et al, 199054 | HAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 600; studied effectiveness of consultative geriatric assessment and follow-up for ambulatory patients | Physical examination,55 new diagnoses, functional impact of patient diagnosis, Katz Index,2 OARS (IADLs),56 SIP57 | MMSE19 showed significantly better cognitive function at 3 mo than controls (P < .05); those > 80 yr improved more than those who were younger (P < .05) | Social support, social activities,58 coping style, emotional health adapted from RAND Health Insurance Study,59 satisfaction60 showed significant benefits for those in lowest quintile of functional health at 1 yr (P < .05) | Changes in health status, overall perceived health with adapted RAND61 | No significant difference | Nursing home placement, incidence of hospitalization, costs, length of stay, office visits, use of diagnostic tests | Medications, nutrition, economic issues, environmental issues |

| Fabacher et al, 199462 | HAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 254; examined the effectiveness of preventive home visits in improving health and function in older adults | Physical examination, health behavior inventory, gait and balance assessment,63 Katz Index,64 IADLs31 significantly higher in intervention group at 1 yr (P < .05) | MMSE19 | GDS28 | Intervention group had significantly increased likelihood of having primary care physician at 1 yr (P < .05) | Environmental hazards, falls, immunization rates significantly improved in intervention group at 1 yr (P < .05); nonprescription drug use increased significantly for control group at 1 yr (P < .05) | ||

| Fretwell et al, 199065 | IGCS (United States) | 6 mo, N = 436; assessed whether early interdisciplinary geriatric assessment could prevent mental, physical, and emotional decline without increasing hospital stay or costs | Katz Index66 | MMSE67 | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS),68 treatment groups emotional function improved (P =.045) at 6 wk | No significant difference | Costs, number of days in institution | ||

| Gayton et al, 198769 | IGCS (Canada) | 6 mo, N = 222; evaluated effects of interdisciplinary geriatric consultation team in an acute care hospital | Barthel Index,70 level of rehabilitation scale (LORS)71 | Pfeiffer short portable mental status questionnaire4 | No significant difference | Health care use, number of days in institution, place of residence at discharge | |||

| Gilchrist et al, 198872 | GEMU (United Kingdom) | 22 mo, N = 222; tested efficacy of an orthopedic geriatric unit in managing older women with proximal femoral fractures | General medical assessment, hip and chest X-ray; more patients in study group found to have new medical disorders than those in control (95% CI, 3.4 to 28.5; P < .025) | Mental function73,74 | No significant difference | Placement of patients, length of hospital stay | |||

| Gunner-Svensson et al, 198475 | ICGS (Denmark) | 11 yr, N = 343; assessed whether social medical intervention would help avoid relocation in nursing homes | Unspecified questions on somatic symptoms, functions, activities | Unspecified questions on mental condition, with emphasis on dementia | Unspecified questions on communication | No significant difference | Housing, medical contact, help in illness, relocations significantly differed in favor of intervention group for women > 80 yr, old (P < .05) | Diet, demographic information (age, gender, marital status) | |

| Hall et al, 199276 | HAS (Canada) | 3 yr, N = 167; evaluated a local health program (LTC program of the British Columbia Ministry of Health) to assist frail older adults living at home | ADLs, chronic disease | Memorial University Happiness Scale,77 UCLA Loneliness Scale,78 Social Readjustment Rating Scale,79 social support | MacMillan Health Opinion Survey,80 health locus of control (HLC)81 | Significantly higher survival rates for those in treatment group at 3 yr (P = .054) | At 2 yr, significantly more of treatment group remained at home (P = .02), and at 3 yr (P = .04) | Smoking, alcohol consumption, nutrition, number of prescription medications | |

| Hansen et al, 199282 | HHAS (Denmark) | 1 yr, N = 344; evaluated nurse- and physician-led follow-up model of home visits to older patients after discharge from hospital | General medical data | Unspecified social data | No significant difference | Number of days in institutions, number of readmissions to hospital, intervention patients were admitted to nursing home significantly less than controls (P < .05) at 1-yr follow-up | |||

| Harris et al, 199183 | GEMU (Australia) | 1 yr, N = 267; aimed at testing differences in medical management and clinical outcome between a designated geriatric assessment unit and two general medical units | ADLs,84 radiology and pathology tests, discharge diagnosis | MMSE19 | No significant difference | Accommodation prior to hospitalization, length of admission, accommodations following discharge | Procedures performed, medications on admission and discharge showed that patients in the GAU discharged on fewer drugs (P < .04) | ||

| Hebert et al, 200185 | HAS (Canada) | 1 yr, N = 503; tested efficacy of multidimensional program aimed at functional decline of older adults | Functional Autonomy Measurement System (SMAF),86 hearing | General well-being schedule,87,88 Social Provisions Scale89 | No significant difference | Admissions, use of health services | Medications, risk of falls | ||

| Hendrikson et al, 198490 | HAS (Denmark) | 3 yr, N = 572; measured the effects of preventative community measures for older adults living at home | Social services, intervention group received more home help (P < .05) | Significantly more deaths in control group than intervention group (P < .05) | Contact with GPs, admissions into nursing home, significantly more medical calls registered to control group (P < .05), significant reduction in hospital admissions in intervention group (P < .01) | ||||

| Sorensen and Sivertsen, 198891 | HAS (Denmark) | 3 yr, N = 585; tested effectiveness of sociomedical intervention aimed at relieving unmet medical and social needs of older adults | ADLs and IADLS92 | Quality of life | Self-rated health | No significant difference | Practical help received, need for more help, number of institutionalizations | ||

| Hogan and Fox, 199093 | IGCS (Canada) | 1 yr, N = 132; conducted trial of geriatric consultation team in acute care setting | Improved Barthel Index94 at 1 yr in intervention group (P < .01) | Mental status scale95 | Intervention group had improved 6-mo survival (P < .02) at 4 mo | Number of days in institution, living arrangements post discharge, referrals to hospital services | |||

| Hogan et al, 198796 | IGCS (Canada) | 1 yr, N = 113; assessed effectiveness of GCS on outcomes related to hospital stay | Barthel Index94 | Improvement in metal status score95 in intervention group (P < .01) | Lower short-term death rates in intervention group (P < .05) | Costs, number of days in institution, number of referrals to community services at discharge higher in intervention group (P < .005), referrals to hospital services, intervention group more likely to receive in-hospital physiotherapy and occupational therapy (P < .025, P < .005, respectively) | Falls, treatment group received fewer medications at discharge (P < .05) | ||

| Inouye et al, 199997 | GEMU (United States) | 2 yr, N = 852; evaluated a multicomponent strategy for prevention of delirium in hospitalized older patients | IADLs,31 Katz Index,2 Jaeger vision test, Whisper test,98 APACHE II20 | Confusion assessment method,99 MMSE,19 digit span test,100 modified Blessed dementia rating scale101,102 showed significantly less incidence of delirium (P = .02), total number of days of delirium (P = .02) and total number of episodes (P = .03) in intervention group | Adherence to intervention | ||||

| Jensen et al, 2003103 | ICGS (Sweden) | 45 wk, N = 362; assessed effectiveness of a multifactorial program for prevention of falls and injury on older adults with high and low levels of cognition | Hearing and vision, Barthel ADL Index,70,104 mobility interaction fall chart,105 DiffTUG (measures ability to walk and carry a glass of water)106 | MMSE,19 concentration | Environmental hazards, medications, falls [number of residents sustaining falls, number of falls, and time to occurrence of first fall significantly longer in high MMSE intervention group (P < .001)], fall-related injuries using Abbreviated Injury Scale107 showed increased injuries in low MMSE control group (P = .006) | ||||

| Kennie et al, 1988108 | IGCS (United Kingdom) | 18 mo, N = 144; assessed whether collaborative care between orthopedic surgeons and geriatric physicians could reduce various outcome measures in women with femoral fractures | Katz Index,2 ADLs significantly better in treatment group (P = .005) | Pfeiffer short portable mental state questionnaire4 | Social prognosis109 | Significantly fewer discharges of patients in treatment group to NHS or private nursing care (P = .03), length of stay in hospital shorter in control group† | |||

| McEwen et al, 1990110 | HAS (United Kingdom) | 20 mo, N = 296; tested effectiveness of nurse-run screening program | ADLs, McMaster health index,111 functional and problem evaluation interview112 | Nottingham health profile,113 Philadelphia Morale Scale,114 significantly better in test group with respect to attitude in own ageing (P < .01) and loneliness (P < .05) at 20-mo follow-up, emotional reaction (P < .05) and isolation (P < .01) perceived to be worse in control group at 20-mo follow-up | No significant difference | Contact with health and social services | Compliance with medication | ||

| Melin and Bygren, 1992115 | HHAS (Sweden) | 17 mo, N = 249; assessed impact of primary home care intervention program on patient outcomes after discharge from a short-stay hospital | Modified Katz Index,66 IADLs116,117 increased at follow-up in study group (P = .04), medical disorders declined in study group at 6-mo follow-up (P < .001); indoor walking,118 outdoor walking118 significantly improved in study group (P = .03) | MMSE19,119 | Social function ratings on activities attended, contacts made during preceding week significantly higher in study group (P = .01) at 6-mo follow-up | Number of admissions to short- term care and rehabilitative care hospitals, number of inpatient care days and outpatient care days showed that study group spent more days in home care than controls (P < .001) but fewer days in long-term hospital care than controls (P < .001) | Number of medications increased in control group at 6 month follow-up (P = .02) | ||

| Newbury et al, 2001120 | HAS (Australia) | 2 yr, N = 100; measured effectiveness of nurse-led health assessment of older adults living independently at home | Hearing and vision, physical condition, Barthel Index,70 mobility | MMSE19 | Unspecified social factors, SF-36 Quality of Life Questionnaire121 and GDS-1513 showed significant improvement in intervention group at 1 yr (P = .032, .05, respectively) | Self-rated health | No significant difference | Housing, admission to institutions | Medication, compliance, vaccinations, alcohol and tobacco use, nutrition, number of problems in each group, number of participants with problems, number of self-reported falls showed significant improvement in intervention group (P = .033) |

| Pathy et al, 1992122 | HAS (United Kingdom) | 3 yr, N = 725; evaluation of case- finding and surveillance program of older patients at home | Townsend score123 | Nottingham Health Profile,112 Life Satisfaction Index124 | Self-rated overall health significantly higher in intervention group (P < .05) | Significantly lower in intervention group (P = .05) | Use of services [domiciliary visits less frequent in intervention group (P < .01), contact with GP, podiatrist, and attendance allowance], questions about meals on wheels and home help, hospital admissions did not differ but duration of stay shorter in younger intervention group (P < .01) | ||

| Powell and Montgomery, 1990125 | GEMU (Canada) | 3 mo, N = 203; studied effectiveness of inpatient geriatric unit at a hospital | Functional activity | Cognitive function improved between discharge and home visit in intervention group† | Depression, life satisfaction | Fewer patients died in intervention group† | Length of stay higher in intervention group but overall admissions lower† | ||

| Reuben et al, 1999126 | OAS (United States) | 15 mo, N = 363; tested effectiveness of outpatient CGA coupled with an adherence intervention | NIA lower extremity battery,127 functional status questionnaire,128 MOS SF-36129,130 showed change scores for treatment group in physical functioning (P = .021); RAS, and BDD131 significantly lower in treatment group (P = .006); physical performance test47 showed treatment effect (P = .019) | MMSE,19 mental health summaries showed significant treatment effect (P = .006) | Patient satisfaction questionnaire,132 Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interaction scale,133 treatment group benefited on social functioning scale (P = .01), and emotional well-being (P = .016) at 15 mo | Treatment group reported less pain129 than control group (P = .043) | No significant difference | Falls | |

| Rubenstein et al, 1984134 | GEMU (United States) | 2 yr, N = 123; assessed effectiveness of geriatric evaluation unit at improving patient outcomes | IADLs,31 personal self-maintenance scale31 showed significant improvement in study patients (P < .01); almost five times as many new diagnoses were made in study group than in controls (P < .001) | Kahn-Goldfarb Mental Status Questionnaire12 | Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale114 showed significant improvement at 1-yr follow-up for study patients (P < .05) | Mortality significantly higher in control group at 1-yr follow-up (P < .005) | Utilization costs, initial placement at discharge, significantly more study patients discharged to their home than controls (P < .05), more than twice as many controls discharged to nursing home (P < .05), study patients underwent more specialized screening examinations and consultations than controls (P < .001), at 1-yr follow-up, controls averaged more than twice as many nursing home days (P < .05) | Medications | |

| Rubin et al, 1992135 | HHAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 200; studied effectiveness of GEM program of health care charges and Medicare | Medical history, Katz Index,66 IADLs | Sensory and communication abilities,136 MMSE56 | Social history, affective, and behavioral status136 | Experimental group significantly more likely to receive home health care than control (P < .01), control group had significantly greater inpatient charges (P < .03) and Medicare reimbursement (P < .005) | Medications | ||

| Rubin et al, 1993137 | OAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 200; assessed effectiveness of outpatient GEM on physical function, mental status, and well-being | Katz Index,66 IADLs46 showed greater improvement and less decline in treatment group at 1 yr (P = .038) | Life Satisfaction Index-Z (LSI-Z)138 | Self-perception of health status (OARS)56 significantly higher for treatment group (P = .006); perceived less decline in health (P = .007) and less activity limitations (P = .024) | No significant difference | No significant differences between groups on long-term nursing placements | ||

| Shaw et al, 2003139 | IGCS (United Kingdom) | 1 yr, N = 274; determined effectiveness of multifactorial intervention after falls in older patients with cognitive impairments and dementia | General medical examination, mobility assessment,140 assessment of walking aids, feet, and footwear141 | No significant difference | Fall-related attendance at accident and emergency department, fall-related hospital admissions | Number of falls, time to first fall, injury rates, medications, environmental hazards142 | |||

| Silverman et al, 1995143 | OAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 442; studied process and outcomes of outpatient CGAs | ADLs,3,144 Barthel Index,94 urinary and bowel incontinence identified significantly more in study group (P < .0001) | MMSE,19 Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale,145 cognitive impairment identified significantly more in study group (P < .0001) | Measures of social support, patient satisfaction with care,146 clinical depression and anxiety sections of diagnostic interview schedule (DIS)147,148 showed significantly lessened anxiety in study group at 1 yr (P = .036); depression identified significantly more in study group (P = .0004) | Self-perceived health status | Nursing home institutionalizations | Changes in participants status, caregiver stress149 significantly less at 1 yr in study group (P = .002) | |

| Strandberg et al, 2001150 | OAS (Finland) | 5 yr, N = 400; determined effectiveness of multifactorial prevention program for composite major cardiovascular events in older adults with atherosclerotic disease | General medical examination, cardiovascular tests (blood pressure, heart rate, and 12-lead resting ECG), blood tests, physical function,151 clinical events | Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer disease tool (CERAD)152 | Health-related quality of life using the 15D,153,154 Zung questionnaire | No significant difference | Health care resource use, hospitalizations, permanent institutionalization | ||

| Stuck et al, 1995155 | HAS (United States) | 3 yr, N = 414; evaluated effect of in-home CGA and follow-up of older adults | Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index,8 balance and gait,156 vision and hearing,9 treatment group required less assistance in basic ADLs11 (P =.02) at 3 yr; IADLs,11 combined basic and instrumental activities117,157 | Kahn-Goldfarb mental status questionnaire12 | GDS,13 extent of social network and quality of social support158 | Costs, admissions to acute care hospital, short-term nursing home admissions, significantly more visits to GP among intervention group (P = .007), permanent nursing home admission higher among control group (P = .02) | Medications, environmental hazards, percentage of ideal body weight159 | ||

| Stuck et al, 2000160 | OAS (Switzerland) | 3 yr, N = 791; examined effects of preventive home visits with annual multidimensional assessments on functional status and institutionalization between high- and low-risk older persons | Gait and balance performance,63 ADLs and IADLs11; intervention group at low baseline less dependent in IADLs (95% CI, 0.3 to 1.0; P = .04) | MMSE19 | GDS13 | Self-perceived general health,161 self-reported chronic conditions | Costs, permanent nursing home admission higher in high-risk intervention group (P = .02) | Medication use15 | |

| Teasdale et al, 1983162 | GEMU (United States) | 1 yr, N = 124; assessed whether a geriatric assessment unit using multidisciplinary team approach affected patient placement outcomes | No significant difference | Source of admission, placement at discharge, location 6 mo postadmission, location of patient after discharge, mean length of stay significantly higher in intervention group (P < .001) | |||||

| Thomas et al, 1993163 | IGCS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 120; tested effectiveness of inpatient geriatric consultation team | Functional Assessment Inventory (FAI),164 physical and activities scales, Katz scale2 | FAI, psychological and social scale164 | Significantly more patients died in control group at 6 mo (P = .01) | Referrals to community service, number of postdischarge GP visits, discharge destination, number of days in institution, control group had significantly more readmissions (P = .02) | FAI—economic scale164 | ||

| Timonen et al, 2002165 | OAS (Finland) | 9 mo, N = 68; studied effects of multicomponent training program focused on strength training after hospitalization | Strength and physical performance (walking speed and Berg Balance scores) significantly improved after the intervention in the study group at 3 mo (P < 0.05). Isometric hip abduction and walking speed significantly improved after the intervention in the study group at 9 mo (P < 0.05). | Community services use | Medication | ||||

| Tinetti et al, 1994167 | HAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 301; evaluated effect of multiple risk factor reduction on incidence of falls | Presence of chronic disease, ADLs,31 vision168 and hearing,169 Sickness Impact Profile (ambulation and mobility subscales),27 risk factor for balance impairment reduced in intervention group at 1 yr (P = .003), impairment in balance and bed to chair transfers reduced (P = .001), impairment in toilet transfers reduced (P = .05) | Depressive symptoms170 | No significant difference | Costs, hospitalizations, number of hospital days, intervention group received more home visits (P < .001) | Room by room number of hazards for falling, falls efficacy scale171; at 1 yr, control group fell significantly more (P = .04), intervention group significantly reduced number of medications (P = .009) | ||

| Toseland et al, 1997172 | OAS (United States) | 2 yr, N = 160; investigated effectiveness of an outpatient GEM team by examining changes in health status, health care utilization, and costs | SF-20,173 (FIM)174–176 | No significant difference | Outpatient utilization (visitation of UPC/GEM clinic, medicine clinic, surgery clinic, emergency room, and total clinic visits), inpatient utilization (number of hospital admissions, hospital days of care, nursing home admissions and nursing home days of care); GEM patients used significantly fewer emergency room services (P ≤ .05), GEM patients used significantly more total outpatient clinic services (P ≤ .01), costs (total inpatient costs, total outpatient costs, nursing home costs, institutional costs, total health care costs); significantly more outpatient cost in GEM patients over 2 yr (P ≤ .05) | ||||

| Tucker et al, 1984177 | OAS (New Zealand) | 5 mo, N = 120; assessed effectiveness of day hospital in geriatric service | Significant increase in Northwick Park ADL index178 at 6 wk for intervention group (P = .002) | Cognitive function179 | Zung index,68 intervention group showed improved mood at 5 mo (P =.011) | Domiciliary services, day hospital costs one third more than alternative | |||

| Tulloch and Moore, 1979180 | OAS (United Kingdom) | 2 yr, N = 295; evaluated effects of geriatric screening and surveillance program on older adults | Screening for medical disorders found significantly greater incidence in study group compared to controls (P < .01); greater proportion of medical problems unrecognized in control group (P < .001) | Rate of hospital admission, outpatient referrals significantly higher in study group (P < .01), time spent in hospital less for the study group than controls (P < .01) | Socioeconomic problems | ||||

| van Haastregt et al, 2000181 | HAS (Netherlands) | 18 mo, N = 316; assessed whether multifactorial program of home visits reduces falls and mobility impairments in older adults | Physical health, control scale, and mobility range scale of SIP 68,182,183 number of physical complaints, Frenchay daily activities184,185 | Mental health section of RAND-36186,187 | Social functioning,188 psychosocial functioning | Perceived health by RAND-36,186,187 perceived gait problems | Falls efficacy scale,171,189 falls, medications, environmental hazards190 | ||

| van Rossum et al, 1993191 | HAS (Netherlands) | 3 yr, N = 580; tested effectiveness of preventive home visits to older adults | Self-rated functional state, hearing and vision problems | Memory disturbances179 | Self-rated well-being,192 loneliness,193 modified Zung index68 | Self-rated health | No significant difference | Costs, use of community and institutional care | |

| Vetter et al, 1984194 | HAS (United Kingdom) | 2 yr, N = 1286; evaluated effectiveness of health visitors on older population of urban (Gwent) and rural (Powys) towns | Townsend score123 | Mental disability,195,196 use of social contacts, self-rated quality of life | Significantly more deaths in Powys (P < .01) | Use of medical and social services, Gwent intervention group used podiatrists significantly more than Powys group (P = .02), significantly more home visits for Gwent intervention group (P = .005) | Availability of caregiver, composition of household, type and quality of housing, participants in Gwent attended more lunch clubs than Powys (P < .05) | ||

| Vetter et al, 1992197 | HAS (United Kingdom) | 4 yr, N = 674; assessed whether health visitors reduced incidence of fractures in older adults | Townsend score,123 medical condition, assessment and improvement of general muscle tone | Falls and fractures, nutrition, medications, environmental hazards | |||||

| Wagner et al, 1994198 | HAS (United States) | 2 yr, N = 1559; tested multicomponent program to prevent disability and falls in older adults | Fitness test, hearing and vision, control group worsened in RAS199 (P < .05), BDD131 (P < .01) and MOS200,201 (P = .05) at 1-yr follow-up | Self-rated health and practices questionnaire | Environmental hazards, alcohol consumption, medications; significantly fewer members of intervention group reported falling than control (difference = 9.3%; CI, 4.1%-14.5%) at 1-yr follow-up | ||||

| Williams et al, 1987202 | OAS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 117; evaluated whether team-oriented assessment can improve traditional health care approaches | Functional status and medical diagnoses203,204 | Social supports203,204 | Health care use, degree of client satisfaction with evaluation, health service use behaviors | ||||

| Winograd et al, 1991205 | IGCS (United States) | 1 yr, N = 197; studied effect of inpatient multidisciplinary geriatric consultation service on health care utilization and functional and mental status | Physical Self-Maintenance Scale, ADLs, IADLs | MMSE19 | Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale114 | Health care use | |||

| Yeo et al, 1987206 | OAS (United States) | 18 mo, N = 205; compared effects of two models of outpatient care on functional health and subjective well-being | SIP57 showed significantly less functional decline in intervention patients (P = .029) and its physical dimension (P = .011) | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS),68,207 Life Satisfaction Index-A (LSI-A)208 Affect Balance Scale (ABS),209 psychosocial dimension of SIP57 | Self-rated health measure210,211 | No significant difference | |||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree