Rectal cancer management benefits from a multidisciplinary approach involving medical and radiation oncology as well as surgery. Presented are the current dominant issues in rectal cancer management with an emphasis on our treatment algorithm at the Lankenau Medical Center. By basing surgical decisions on the downstaged rectal cancer we explore how sphincter preservation can be extended even for cancers of the distal 3 cm of the rectum. TATA and TEM techniques can be used to effectively treat cancer from an oncologic standpoint while maintaining a high quality of life through sphincter preservation and avoidance of a permanent colostomy. We review the results of our efforts, including the use of advanced laparoscopy in the surgical management of low rectal cancers.

Colorectal cancer remains the number one abdominal-visceral cancer afflicting both men and women in America. With more than 104,000 new cases diagnosed each year, the incidence of colorectal cancer, while decreasing slightly over the past decade, still remains terribly high. The fact that this cancer is preceded by a premalignant condition of a polyp that can be eradicated by colonoscopy and polypectomy makes this high incidence all the more frustrating. There are a multitude of reasons for avoidance of screening; however, the greatest fraction seems to be the patients’ reluctance to undergo the discomfort of bowel preparation as well as fears of the need for a permanent colostomy. Of all colorectal cancers diagnosed annually in the United States, 40,000 of these are rectal cancers. It is in this region that concerns for ultimate cure are higher, prevention of recurrence is more challenging, and the risk of a permanent colostomy is a very real possibility.

The current TNM classification system has evolved as a very useful way of discussing all cancers ( Table 1 ). Historically, rectal cancer was discussed in Duke’s stage A, B, C, and D, which correlates with TNM Stage 1, 2, 3, and 4. For the purpose of this article as well as any discussion of rectal cancer in the 21st century, the TNM classification system should be used ( Table 2 ). In terms of discussing matters, Stage 1 disease is node-negative rectal cancer confined to the rectal wall. Stage 2 disease is node-negative rectal cancer that has extended through the rectal wall. Stage 3 disease is any T stage with node positivity. Stage 4 disease is any T or N stage with metastatic disease present. It is essential to emphasize and review this so we can have a common lexicon to discuss cancer therapy.

| T Staging | |

| T1 | Lamina propria or submucosa or ≤2 cm |

| T1a | <1 cm |

| T1b | 1 to 2 cm |

| T2 | Muscularis propria or >2 cm |

| T3 | Subserosa or pericolorectal tissues |

| T4 | Tumor directly invades other organs or structures and/or perforates visceral peritoneum |

| T4a | Perforates visceral peritoneum |

| T4b | Directly invades other organ or structures |

| N Staging | |

| N1 | Metastasis in 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes |

| N1a | 1 node |

| N1b | 2–3 nodes |

| N1c | Satellites in subserosa without regional nodes |

| N2 | Metastasis in 4 or more regional lymph nodes |

| N2a | 4–6 nodes |

| N2b | 7 or more nodes |

| M Staging (Distant Metastasis) | |

| M1a | One organ |

| M1b | >one organ or peritoneum |

| TNM Stage | Duke’s Stage | |

|---|---|---|

| I | T1–2, N0, M0 | A |

| II | T3–4, N0, M0 | B |

| III | T any, N1–3, M0 | C |

| IV | T any, N any, M1 | D |

A multitude of issues exists regarding the treatment of patients with rectal cancer. Questions surround both the surgical management as well as the use of adjuvant therapy, and they impound in the literature. Concerns are always focused first and foremost on how various treatment strategies affect recurrence rates and survival; however, in patients with rectal cancer quality of life and body image are closely intertwined with these disease-specific outcomes. Because of this, the major issue of abdominoperineal resection (APR) rates with resulting permanent colostomy comes into focus.

To achieve the goals of both optimal oncologic outcomes with a high quality of life, multimodal therapy has come to the forefront of rectal cancer management. Questions regarding both chemotherapy and radiation are multiple. The most basic question, however, is whether adjuvant treatment should be given preoperatively or postoperatively.

From a surgical standpoint, technical issues involve the necessity of performing a total mesorectal excision as well as what the role of local excision may be. To add even further complexity to this, we must consider whether these surgical options may be modified based on the response of the rectal cancer to chemoradiotherapy. Last, as complete response rates to neoadjuvant therapies improve, how does this affect cancer treatment? The purpose of this article is to delve into some of these matters and address them outlining the approach taken in a multidisciplinary program of rectal cancer management in a community cancer center.

The treatment of rectal cancer in 2011 has progressed dramatically. After 2 decades of discussions regarding the timing of chemotherapy and radiation, there is general consensus among rectal cancer experts that both have enormous utility in the preoperative setting. That being stated, there is a great deal of discussion regarding the specifics of both modalities.

With regard to radiation therapy, major questions revolve around when it needs to be used, short-course versus long-course radiation, and how high a dose should be given to optimize the utility of the treatment with the least morbidity to the patient. In addition, newer regimens call into question how the treatment should be fractionated.

Beyond the decision of which type of chemotherapeutic agent is chosen, we need to consider the route of administration, whether given orally or intravenously, and if intravenously if given in a bolus or via continuous venous infusion. But even more generally, despite all current enthusiasm for neoadjuvant therapy we must still consider which situations arise where neoadjuvant therapy is ultimately not necessary.

Most recently, the Medical Research Council (MRC) published their results regarding routine short-course preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. This study was a randomized trial including 80 centers in 4 countries with a total of 1350 patients diagnosed with operable adenocarcinoma of the rectum. What this study found was that for all stages of disease there were lower local recurrence rates at the 5-year interval using short-course preoperative radiation therapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiation. These results were quite dramatic, with a decrease from 6% to 0% local recurrence in the preoperatively treated group for stage 1 disease, 12% to 2% for stage 2 disease, and 25% to 10% for stage 3 disease when compared with patients who underwent postoperative radiotherapy ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). These data argue soundly for the preoperative use of radiation therapy for all stages of disease, even patients with stage 1 rectal cancer.

As to the exact dose to be used, high-dose radiation is needed to be effective in the treatment of rectal cancer (4500 cGy). This was the dose we started using in 1976; however, we now favor as a routine, the dosage of 5580 cGy. This is based on our experience published from our time at Thomas Jefferson University, where we examined our local failures and found a decreased recurrence rate with a presacral boost of treatment. The intellectual basis of this has to do with the radiation sensitivity in rectal cancer and a dose response curve that shows clearly that there is a marked increase in the slope of response showing between 4500 cGy and 5500 cGy with a concomitant 50% reduction in pelvic relapse.

To better communicate the tumor sensitivity in response to radiotherapy, tumor regression grading (TRG) has been added to the pathologic evaluation of rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy, giving a sense of the tumor’s sensitivity and response to radiotherapy. A TRG of 1 corresponds to minor regression of cancer, but there remains a dominant tumor mass with obvious fibrosis. A TRG of 2 corresponds to moderate regression with obvious fibrosis of the dominant tumor, with regression of 20% to 50% of the tumor. TRG 3 shows a good regression with dominant fibrosis and/or mucous substance outgrowing the tumor mass with regression of more than 50% of the tumor. TRG of 4 corresponds to a complete pathologic response.

Although this phenomenon of tumor regression has piqued the interests of many students of these studies for some time, more recently this effect has been linked to outcomes. A tumor that demonstrates a high grade of regression after neoadjuvant therapy followed by curative resection has led to improvement in overall survival. In a study by Rödel and colleagues, which was a follow-up analysis of a large prospective randomized trial comparing adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer in Germany, it was shown that the patients who demonstrated a complete response to neoadjuvant radiotherapy (TRG 4) had an 86% 5-year survival rate compared with a 63% 5-year survival rate for patients with no regression or minor regression of tumor (TRG 0 and TRG 1 patients, respectively). This has focused our attention on trying to optimize tumor response to high-dose preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Although this represents an exciting field of interest, what remains to be seen is whether complete responses (CR) represent the selection of the most favorable rectal cancers or if this is altering the natural course of the disease.

The surgical management of rectal cancer is a large focus of our discussion, especially that of sphincter preservation in the distal third of the rectum. In viewing the treatment algorithm of rectal cancer from a surgical perspective, the first discussion involves whether sphincter-preservation surgery or an abdominal perineal resection with permanent end colostomy is appropriate, how to extend the performance of sphincter preservation, and what is the role of local excision. Additionally, in the age of minimally invasive surgery one must ask, what is the role of laparoscopy?

Sir Earnest Miles in 1907 reported on an abdominal perineal resection for the curative therapy of rectal cancer. Although this work was a tremendous advance in the treatment of patients with rectal cancer, it unfortunately remains the dominant approach to rectal cancer for the next 100 years. Although positively affecting local recurrence rates and survival in the treatment of rectal cancer, it affected the patients’ quality of life and body image at an extremely high premium. Foremost in the thoughts of the patient with low rectal cancer is avoidance of a permanent colostomy.

The challenges of rectal cancer surgery revolve around the anatomic confines of the bony pelvis. The inability to excise things laterally and the difficulty in reaching deep into the pelvis make it technically challenging to excise the cancer and perform an anastomosis, leaving the sphincter muscle intact. Although distal tumor margins are obviously a justifiable concern, the focus over recent years has rightly shifted toward obtaining clean lateral (or radial) margins as well. After preoperative radiation, the challenge of excising a tumor has been compounded by the loss of a palpable mass. This can result in the inability to be confident about the tumor’s location as the surgeon attempts to grasp below the cancer and adequately place a surgical clamp or stapling device.

The issue of proper margins surrounding rectal cancer has been highlighted by works published in the pathology field. In 1986, Philip Quirke and colleagues published a seminal work on the subject of examining margins of patients with rectal cancer. His focus was not on the distal margin, as that could be achieved by cutting out the sphincter, but rather on the radial margin. In this group of 52 patients, they identified 26 patients who had low anterior resections and 26 patients who had abdominal perineal resection. A disappointing 30% of patients had spread to their radial margins. This was equally shared by the low anterior resection and APR groups. Of the patients who had a positive lateral margin, 75% of these patients developed a recurrence. Only one of the patients without circumferential margin positivity developed a recurrence, giving a local recurrence rate of only 3% in the negative margin group.

To understand this phenomenon better, let us look at the geometry of the entire pelvis. The bony pelvis creates a funnel filled by the cylindrical tissue of the rectum and mesorectum. As the funnel narrows, the space between the bony sidewall and the mesorectum containing the cancer becomes much smaller. With this in mind, it becomes obvious to see why it is the lateral margins rather than the distal margins where problems with adequate margins arise ( Fig. 3 ).

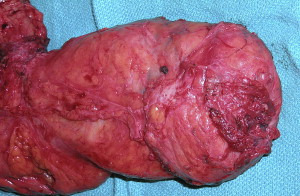

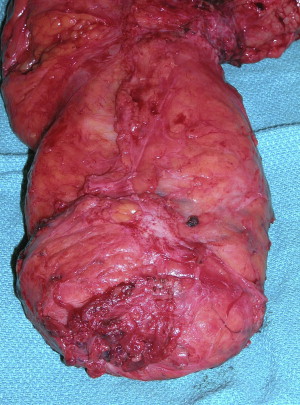

Surgical technique matters. Although this is an inherently obvious point in the operative treatment of all visceral cancers, it has been brought to the forefront as a central issue in rectal cancer and its effective treatment. The most important day in the treatment of any patient with rectal cancer is their operative day. The need for a complete oncologic resection is paramount. A multitude of trials designed and funded nationally control very tightly radiation and chemotherapeutic parameters, but treat the operating room as a black box where no one is sure what has happened. R.J. Heald should be credited for refocusing attention on optimal operative technique and its impact on rectal surgery. In the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1988, he described eloquently the “Holy Plane” of Rectal Surgery. This has come to be known as total mesorectal excision (TME). Although many in the United States and elsewhere in the world consider this a statement of current good oncologic rectal surgery, Heald described it clearly and drew the attention of the surgical community as to what exactly a TME entails ( Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Total mesorectal excision

The 3 basic principles in developing this plane of dissection for a total mesorectal excision really focus on the embryologic nature of where one is working.

- 1.

Resection of rectum and mesorectum as an intact unit using sharp dissection between the parietal and visceral planes of the pelvic fascia.

- 2.

Visceral fascia involves the entire rectum and its mesentery.

- 3.

Dissection in this plane reduces autonomic nerve damage and reduces local recurrence.

Resection of the rectum working in what is termed “The Holy Plane” ensures excision of the whole rectum and mesorectum as one distinct lymphovascular entity. The tumor is more apt to spread initially along the field of active lymphatic and venous flow.

The cancer itself is generally limited by the embryologic envelope that the rectum itself sits in. Ultimately, as the cancer develops and progresses, if left unchecked it will grow across this and become a T4 invasive cancer. However, this is a much later stage of the disease process, and by following the 3 basic principles in developing the plane, one can usually stay out of trouble. The first principle is the recognition of mobility between the tissues of different embryologic origin. The second is the sharp dissection with good light under direct vision. The third is that of gently opening the embryologic plane with the essential addition of continuous traction on the tissues while avoiding actual tearing of the mesorectum.

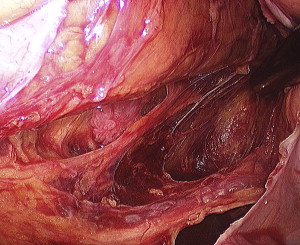

Outside of the “Holy Plane” lie the autonomic nerve plexuses, pelvic veins, and internal iliac nodes. A key to the dissection is identifying the autonomic nerves and staying immediately anterior to them. There are actually 2 separate plexus planes, one inside and one outside the inferior hypogastric plexus, and by identifying the hypogastric plexus and sweeping it posteriorly, one can be reasonably sure of being directed into the proper plane ( Fig. 6 ). One must then follow the nervi erigentes and pelvic plexuses and stay medial to these to avoid disturbance of sexual function while at the same time maintaining a proper oncologic resection.

Heald’s contributions in the description of the technique of total mesorectal excision cannot be overstated in the treatment of rectal cancer. First, he described his own personal low local recurrence rates, roughly 50% less than what was being reported in the literature at the time. But subsequently, large population studies with national audits of rectal cancer outcomes were performed showing surgeons who were trained in proper TME technique demonstrated marked diminution of their local recurrence rates. This effect was shown in the Norwegian Rectal Cancer Project, which addressed the issue of TME directly. In this study, surgeons were educated about proper TME, including master classes with R.J. Heald. These surgeons reported performance rates of a proper TME as 78% in 1994 increasing to 92% in 1997. Isolated local recurrence rates were 4% for patients receiving TME versus 9% for patients without TME. In addition, this correlated with an improvement in overall survival after TME, with 5-year survival rates of 73% after TME versus 60% after conventional surgery.

The quality of oncologic resection has clearly been acted on by attention to total mesorectal excision, and the result has been an improvement in overall oncologic care. The next step forward in the treatment of patients with rectal cancer has to be improving their quality of life. Clearly nothing affects as greatly the quality of life of a patient with rectal cancer as the ability to avoid permanent colostomy and maintain normal function. The challenge in operating on a low rectal cancer during the abdominal approach is how to get beneath the cancer and perform an anastomosis. In the upper rectum, this is nonproblematic and from a technical standpoint is quite similar to a sigmoid or rectosigmoid excision. Resections that include the distal rectum are where the troubles lie from a technical standpoint for the surgeon.

Compounding this challenge is the question “what is an adequate margin for a distal rectal cancer.” Every decade an additional maxim seems to be put forward and one debunked. Originally there was a 5-cm rule postulated as necessary for proper oncologic resection. This was then revised to a 2-cm rule in the 1990s. In the early portion of this century the question that has been raised is whether less than a 1-cm margin is sufficient so long as it is an R0 resection. The reason that this discussion is germane relates to the persistently high incidence of abdominal perineal resection. The original Swedish rectal cancer trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1997 involved 908 patients treated with surgery alone versus surgery and radiation. Both cohorts had an APR rate of more than 50%. The last major rectal cancer management trial published in the United States (NSABP R-03 Trial) had to be halted because of lack of accrual. However, in the preoperative radiotherapy group, APR rates were 50% and even higher in the surgery-alone arm. The German Rectal Cancer Trial (CRO-CAO-A10-94) showed an APR rate of 61% in the preoperative radiotherapy group compared with an APR rate of 81% in the postoperative radiotherapy group ( P = .004). In the Polish colorectal study group, APR rates were 40% in both the short- and long-course radiotherapy group. With data such as these as a background, it is understandable why there is such concern in the medical and lay communities regarding the need for a permanent colostomy in the care of patients with rectal cancer.

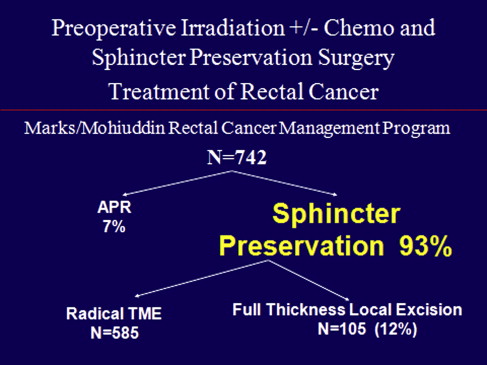

Against this background, we consider our program of rectal cancer in a teaching, community hospital center. Our rectal cancer management program using high-dose radiotherapy originates in 1976 at Thomas Jefferson University. This represents the first experience of sphincter-preserving surgery after high-dose preoperative irradiation. It is worth noting that at the time many considered it malpractice to even operate on the pelvis after irradiation, because of concerns in the 1970s regarding morbidity and mortality when operating in the irradiated field.

There are 6 keys to extending sphincter preservation in rectal cancer management. This approach, originally developed at Jefferson, and currently used in a community colorectal surgical unit at our hospital, includes 6 factors that must be incorporated to alter the rate of sphincter preservation ( Fig. 7 ). If our goal is to decrease APR rates from 40% to 60%, as noted in the major national trials discussed earlier, to 7% in our experience, we need to focus on the following:

- 1.

Using higher radiation therapy doses, on average now to 5580 cGy.

As explained earlier, this relatively small escalation in radiation dose has an exaggerated effect on tumor regression, which we are able to take advantage of.

- 2.

Base decisions on sphincter preservation on the status of the cancer AFTER completion of chemoradiotherapy.

Although this is a basic tenet of our rectal cancer management program at Lankenau Hospital, it represents a major departure for many. The oncologic community (surgical and medical) has been taught that it is the initial presentation of the cancer that will dictate subsequent treatment. This lack of plasticity of thought has hindered surgeons from reaping perhaps the most significant benefit of tumor downstaging for rectal cancer after chemoradiation, the preservation of the sphincter. Let us be clear that the dictum that treatment must be based on the initial presentation of the cancer where sphincter preservation hangs in the balance for many low rectal cancers, must be abandoned. Downstaging after neoadjuvant therapy clearly has a dramatic effect on surgical options.

- 3.

Accepting distal margins of resection from the cancer as small as 5 mm in length.

Although we are certainly not advocates for minimal margins for cancers in the proximal rectum, for adenocarcinomas of the distal 3 cm of the rectum accepting smaller distal margins on an otherwise R0 resection allows us to apply sphincter-preservation techniques in situations that would not be possible if the 2-cm rule was invoked. This strategy, as you will see, has been supported with impressive oncologic results.

- 4.

Extended interval between completion of radiation therapy and surgery (8–12 weeks).

Although we are in the process of researching this point, it has been our strong clinical impression that by extending this period from our original 6- to 8-week period following radiation to 8 to 12 weeks, additional downstaging occurs. With this further tumor regression comes improved applicability of sphincter preservation.

- 5.

Transanal abdominal transanal proctosigmoidectomy (TATA) surgical technique.

This operation allows for the creation of a known distal margin to the cancer even after downstaging. This technique, only for cancers of the distal 3 cm of the rectum, combats both the difficulty of obtaining a safe margin as well as the ability to perform a low anastomosis.

- 6.

Full-thickness local excision (FTLE).

This is another technique that allows for distal rectal cancers to be excised with sphincter preservation, also taking advantage of the downstaging that occurs after chemoirradiation. FTLE is used only for select tumors that have an excellent response to chemoradiation therapy.