20. Management of stroke

Marion Ireland

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Gain knowledge of the background to and pathophysiology of stroke, and identify the relevance of nutritional screening and assessment in stroke management;

• Demonstrate a critical understanding of the effective management of dysphagia in stroke patients, including the roles of enteral nutrition, texture modified diets, oral nutritional support and the key importance of hydration;

• Understand some of the complexities of the ethical considerations relating to enterally fed stroke patients; and

• Gain insight into the dynamic process of neurorehabilitation, and of the approach required to secondary prevention and discharge planning in stroke patients.

Introduction

Stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK, and the third major cause of death, accounting for 11% of all deaths. 1 Most people survive a first stroke, but are often left with significant morbidity.

Stroke is defined as a sudden interruption in the blood supply to an area of the brain, depriving the affected point of oxygen and causing death of brain tissue, the neurological consequences of which can be profound, resulting in long-term disability, especially in the elderly. 2 In addition, the World Health Organization definition includes that the focal or global signs of disturbance of cerebral function will last more than 24 hours or leading to death with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin. 3

A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is defined as stroke symptoms and signs that resolve within 24 hours, which can in fact resolve within minutes or a few hours of onset. 4

In recent years, there is a growing body of evidence for more effective primary and secondary prevention of stroke, recognising that it is a preventable and treatable disease, rather than a consequence of ageing that inevitably results in death or severe disability. 4

Epidemiology of stroke

Stroke is the third most common cause of death in the Western populations, following ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and cancer, and remains a major health problem in the UK. The incidence of stroke is strongly age-related, with more than 75% of strokes occurring in people aged above 65 years. Approximately 125,000 new or recurrent strokes occur each year in the UK, but up to 350,000 people are affected at any one time, of which ~50% will make a full recovery with no obvious residual disability. 5

Between 20 and 30% of people die within the first month of a stroke occurring and it remains the largest cause of adult disability. Approximately one-third of people who have a stroke are left with a long-term disability. Stroke also has a causative role in further morbidities such as depression, dementia and epilepsy.

Types of stroke

There are two main types of stroke which occur:

• Ischaemic or cerebral infarction—this accounts for ~80% of strokes; caused by a clot narrowing or blocking cerebral blood vessels, which results in brain cell death due to oxygen deprivation.

• Haemorrhagic stroke: intracranial haemorrhage ~10%, subarachnoid haemorrhage ~5%, ~5% unknown origin. This is a bursting of weakened or damaged blood vessels, resulting in bleeding within the brain, or on the brain’s surface, both of which cause damage. 5

Risk factors

As with any vascular disease process, there are several factors involved that can increase risk of stroke, many of which are modifiable. Risk factors which contribute to the development of atherosclerosis include hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol consumption and raised lipids.

Additionally, the presence of other cardiovascular conditions such as ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery stenosis, atrial fibrillation, prosthetic valves and cardiomegaly are directly associated with increasing the risk of ischaemic stroke. 5

There are some obvious nutrition-related risk factors, such as hypertension, raised lipids, obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, all of which can be affected and improved by modification of dietary intake. There is also a growing evidence base for factors such as raised homocysteine levels, which are associated with poor dietary intake of folate and vitamins B 6 and B 12, and this is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, further emphasising that nutrition has a part to play in both primary and secondary prevention of stroke.

Pathophysiology of stroke

Residual deficits can depend on the location and extent of a stroke. Some deficits are permanent in some patients, but can resolve in others, depending on the damage the brain has incurred.

The pathophysiology of stroke can include:

• Aphasia—a loss of language, affecting speech, reading and interpretation;

• Apraxia—disordered skilled purposeful movement, e.g. affecting ability to feed self;

• Ataxia—tremor or poor motor control;

• Altered appetite control;

• Behavioural difficulties, e.g. inappropriate social behaviours;

• Changes in mobility, balance;

• Cognitive impairment;

• Continence problems;

• Depression;

• Dysphagia—difficulties in swallowing;

• Dysphasia—impairment of speech and verbal comprehension;

• Emotional lability;

• Fatigue;

• Hemianopia—visual problems;

• Hemiplegia—paralysis affecting one side of the body;

• Impaired memory and perception;

• Neglect; and

• Sensory loss—altered taste or smell.

Although dysphagia is closely associated with undernutrition in stroke patients, many of these features of stroke have a significant impact on nutritional intake and require appropriate management of these deficits to ensure that nutritional status does not suffer as a result. The practicalities of mealtimes in patients with significant residual disabilites can make the process of ‘plate to mouth’ a complex one. For example, a patient with apraxia or ataxia may be unable to feed themselves; a patient with neglect or hemianopia may only be able to see or access half of their plate of food; or a patient with impaired memory may forget to eat, or have forgotten that they have already eaten.

Nutritional screening

Nutritional screening should be a simple procedure that can be carried out by any member of the multidisciplinary team, to detect each patient’s risk of nutritional problems, and a plan of action for the management of them. Screening of all patients should ideally be carried out within 48 hours of admission to hospital and repeated regularly throughout the episode of care. 6 Baseline information required should include height, weight, body mass index and percentage weight change. 7 Malnutrition occurs in approximately 15% of all patients admitted to hospital, increasing to approximately 30% within the first week. It carries with it a strong association with poorer functional outcome and slower rate of recovery. 8

In addition, SIGN 78 recommends that a nutritional screening tool for use in stroke patients should focus on the effects of stroke on nutritional status, e.g. presence of dysphagia, ability to eat, rather than solely focusing on pre-existing nutritional status. 9

Nutritional screening helps to identify any immediate or pre-existing nutritional problems, and helps direct appropriate action required to manage this in the short term. It should also direct referral to a dietitian for assessment and management of nutritional risk. However, as with all screening tools, it is important that all staff carrying out screening still use clinical judgement to avoid inappropriate referrals, or more importantly, if there is cause for concern when a patient is not identified as high risk by a nutritional screening tool.

Nutritional therapy and dietetic intervention

Nutritional assessment

Nutritional assessment of patients is a more detailed evaluation of each patient’s nutritional requirements and current nutritional status. It should involve an in-depth assessment of a patient’s clinical condition, and any physiological changes therein affecting nutritional status, biochemical and anthropometric measurements, prescribed medications and any dietary factors which will influence current intake.

The prevalence of malnutrition, and the impact that this has on the patient’s condition, is well documented, including increased frequency of infection, increased rate of pressure sores, increased morbidity and mortality, increased length of hospital stay, increased levels of apathy and depression and poorer functional outcomes. 10

The risk of malnutrition in stroke patients varies, but it is recognised that nutritional status can worsen during admission, and that undernutrition following admission is associated with increased case fatality and poor functional status at 6 months. 11 It is important to assess beyond merely swallowing problems and poor intake, and look thoroughly at the mechanics of plate to mouth and the entire meal process, to ensure that the impact of any residual disabilities is minimised.

Nutritional assessment and estimation of requirements are based on predictive equations such as Schofield, which allow estimation of basic requirements of energy and protein and fluid, along with micronutrients, e.g. trace elements. 12 The outcome of a patient’s swallow assessment is integral to ensure that nutritional intervention is delivered appropriately in patients with identified dysphagia.

It is unclear to what extent hypermetabolism and hypercatabolism occur post-stroke, with estimations for the increase in metabolic rate following stroke ranging from 10 up to 50%, depending on the severity and clinical consequences of the stroke, and clinical judgement is required when estimating the increase in resting energy expenditure. 13 Catabolic effects vary according to the individual, but usually persist for the first few weeks, then begin to resolve in the following weeks and months.

Hyperglycaemia following stroke occurs as part of the metabolic response to injury, related to the stress hormone levels. Optimisation of blood glucose control is essential in order to minimise the risk of worsening the effects of stroke, and some studies have shown that even in the absence of diabetes, an initially high blood glucose following stroke is a predictor of poor outcome. 14 Insulin therapy is recommended in all patients with diabetes to ensure that blood glucose is controlled within the recommended levels. 4

Undernutrition, in stroke patients in particular, is associated with a higher stress response, increased frequency of infections, poor functional status and reduced survival. 5 Risk of undernutrition and dehydration are significant in stroke patients, and their causes are complex and often multifactorial. This emphasises the importance of good management of undernutrition at each stage of the patient’s journey, to ensure the minimum impact on nutritional status is made. The management of dysphagia in stroke patients is of the utmost importance, due to the risk of undernutrition that accompanies it. However, even in patients without dysphagia, risk of undernutrition is significant in stroke, ensuring that robust measures for nutritional support should be in place in all stroke units, and for all stroke patients.

Swallow screening

Dysphagia, which is a difficulty in swallowing, is a common and clinically significant complication following stroke which can result in aspiration. 8 Aspiration can be defined as when solids or liquids that should be swallowed into the stomach are instead breathed into the respiratory system, and the presence of aspiration is associated with an increased risk of developing an aspiration pneumonia, and other bronchopulmonary infections. 9

Both NICE 2004 and SIGN 78 recommend that, following acute stroke, all patients should be screened for dysphagia by an appropriately trained healthcare professional before being given food, drink or medication.

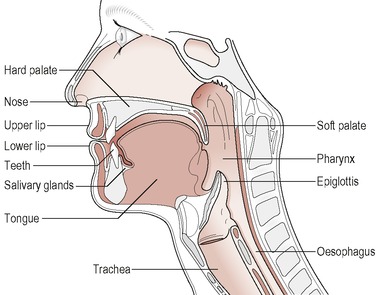

A water swallow test is often used to help identify a patient’s risk of aspiration (Figure 20.1). This involves giving the patient teaspoons of water, and then observing for any signs such as delayed initiation of swallowing, coughing or altered voice quality. This type of test has good reported clinical sensitivity of > 70%, and between 22 and 66% sensitivity for prediction of aspiration. 15

|

| Figure 20.1 • |

As with all screening tools, clinical judgement is essential for ensuring appropriate referral to a speech and language therapist, for full assessment of swallow, and appropriate management of dysphagia, and to prevent patients from being put at risk if aspiration is not clearly identified on screening.

NICE 2008 recommends that if the admission screen indicates a swallowing problem, that a specialist assessment should take place within 72 hours of admission. 4

Dysphagia defined

Dysphagia, which is a difficulty in swallowing either food or fluids or both, is a significant complication in patients following stroke. In stroke patients, it presents as difficulty in safely moving food or fluid from the mouth to the stomach without aspiration often due to difficulties at the oral preparation stage with chewing and tongue control. 9 Incidence varies greatly, ranging from 64 to 90% in patients conscious during the acute phase, with aspiration rates, including silent aspiration, ranging from 22 to 42% on videofluoroscopy. 8

Dysphagia has serious implications for patients following stroke, such as increased potential for undernutrition and dehydration, if it is not managed effectively. With increased risk of aspiration, there is a higher risk of respiratory infection, which may develop into aspiration pneumonia. Nutritional problems tend to be exacerbated by the presence of dysphagia, and patients with pre-existing malnutrition are at even greater risk.

Management of dysphagia

Effective management of dysphagia is of key importance following stroke, in order to prevent undernutrition and dehydration from occurring as far as possible. This must involve multidisciplinary working and good communication between involved practitioners. Once a full assessment of dysphagia by a speech and language therapist has taken place, the appropriate route of feeding can be identified, making it more attainable to meet nutrition and hydration requirements.

The route of feeding initially is often a combination of oral and enteral feeding, and the management of each transition through the different stages of this spectrum is a crucial part of effective dysphagia management.

Enteral nutrition

Nutritional intervention following stroke can often involve enteral feeding in patients who are unable to meet their requirements safely or consistently via oral diet and fluids, and for some patients, oral intake is contraindicated completely.

Enteral feeding is the introduction and delivery of nutrients via the gastrointestinal tract, by means other than eating. 16 Contraindications to enteral nutrition are patient refusal, patients with a non-functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and where it is inappropriate to feed for ethical reasons. 17 Enteral feeding in stroke tends to focus on nasogastric and gastrostomy feeding, both of which are used in patients unable to meet their requirements or who are at risk of disease-related malnutrition.

Nasogastric feeding

Tube placement involves a fine-bore nasogastric tube being inserted transnasally into the stomach. The tubes are usually between 6 and 9 mm French gauge, made from polyurethane, PVC or silicone. Nasogastric feeding is ideal in the acute setting, for patients who require short-term feeding, identified as less than 4 weeks. 2 It can be used longer term if other options such as gastrostomy feeding are contraindicated or not appropriate. 19

Care is needed in the insertion of nasogastric tubes, which should be carried out by suitably trained personnel, particularly in stroke patients where there is impaired or absent swallow, as getting patients to swallow during tube placement can help with insertion. The position of the tube should be confirmed by aspiration of stomach contents and checking that the pH of aspirate is < 5.5, indicating gastric contents, as per the National Patient Safety Agency Guidelines from 2005. 20 The position of a nasogastric tube should be confirmed before each use by aspiration of stomach contents, and radiological confirmation should only be used when there is ongoing difficulty in obtaining aspirate, or concern regarding the tube position that cannot be otherwise resolved.

Consent should be obtained for placement of all feeding tubes, and this can prove difficult in stroke patients, as there may be cognitive impairment, and significant communication difficulties, along with confusion and poor understanding, particularly immediately post stroke. Medical staff usually take responsibility for obtaining consent for procedures considered invasive, or identifying when patients do not have the capacity to consent, and putting alternative arrangements for procedures to take place, such as per the guidance for consent and capacity from the British Medical Association in England and Wales, or the Adults with Incapacity Act in Scotland.

Results from the FOOD Trial indicated that early enteral feeding, clarified as within 7 days, may reduce mortality, and that dysphagic stroke patients should be offered enteral feeding via nasogastric tube within the first few days of admission. However, it also identified worse quality of life in patients allocated early tube feeding, concluding that early feeding may keep patients alive, but in a severely disabled state when they would otherwise have died. 21 The RCP Stroke Guidelines go a step further, indicating that patients should be fed within the first 24 hours, based on the recommendations of the FOOD Trial and the observed reduction in mortality, with further consultation with patient representatives regarding the timing of initiation of feeding for maximum benefit.

Refeeding syndrome

Early enteral feeding is recommended in stroke patients, but in circumstances where a patient has received little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 days, risk of refeeding should be identified and managed appropriately. 21 Refeeding is defined as ‘severe fluid and electrolyte shifts and related metabolic implications in malnourished patients undergoing refeeding’, 16,18 and there are established guidelines regarding the replacement of electrolytes and the reintroduction of fluids and nutrients in at risk patients, such as those developed by Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals in 2003.

Nasal bridle tubes

Nasal bridle tubes are enteral feeding tube retaining devices that are increasing in use in patients who repeatedly displace nasogastric tubes, e.g. in patients who are confused following stroke. The use of nasal bridle loops has been shown to have few complications and minimal discomfort for the patients, and in one prospective study showed a reduction in 30-day gastrostomy mortality, in part due to better selection of patients for gastrostomy, and also that bridle loops allowed patients an average 10 days’ nutrition prior to either recovery or gastrostomy placement. 22 The NICE Guideline for management of acute stroke endorses the consideration of using nasal bridle tubes in stroke patients who are unable to tolerate a nasogastric tube. 4

Gastrostomy feeding

Gastrostomy feeding is generally used for patients requiring longer term nutritional support, usually identified as more than 4 weeks. 4 Gastrostomy tubes are placed directly into the stomach, endoscopically, surgically or radiologically, and each patient should be fully assessed prior to placement, to ensure that there are no contraindications to placement, e.g. previous abdominal surgery.

Previously, a number of studies comparing nasogastric to gastrostomy feeding showed that there was better success in the administration of feed, less interruption to feeding regimen and lower risk of aspiration with gastrostomy feeding. As a result, patients were more consistently hydrated and fed, and nutritional status improved, and with it many of the functional measures associated with poor nutrition, such as increased frequency of infection, increased risk of pressure areas, depression and loss of muscle mass.

However, the FOOD Trial found that there were no clinically significant benefits of gastrostomy feeding compared to nasogastric feeding, and also found a reduction in poor outcomes with nasogastric feeding. 21 The recommendation from this was to use nasogastric feeding initially for the first 2–3 weeks post stroke, unless there was a clear practical reason to use gastrostomy. An additional finding of interest was that the gastrostomy group had a higher rate of pressure sores, which raised the possibility that these patients may move less or be nursed differently.

Poor outcome following gastrostomy insertion, as concluded by the FOOD Trial, must consider that patient selection is a factor, as those requiring gastrostomy are patients with poor nutritional intake and status, and the poorest prognosis. This links in with the finding that, although early enteral feeding is recommended, and does not cause any harm, this can keep patients alive but in a severely disabled state where they would otherwise have died; that is, survival itself does not equate to survival with good outcome.

Please refer to the chapter on enteral nutrition for further guidance on this aspect of patient care.

Texture modified diets

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree