fatigued, and unable to move around by themselves, the risk of developing one or more pressure ulcers is very high. Shear, friction, prolonged presence of moisture associated with incontinence, age-related changes in skin, and poor nutrition further compound the risk (11).

TABLE 26.1 Context assessment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear (Table 26.2, a simplification of the Braden Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment tool—for complete details, refer to the original tool).

TABLE 26.2 Braden pressure ulcer risk assessment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

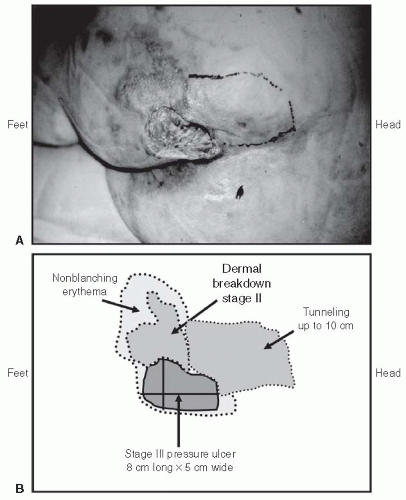

The wound, including the type (etiology), location (Fig. 26.1), duration, description of the structure and base/surface, dimensions—best to document with a labeled photograph or diagram (Fig. 26.2), exudate, and bleeding (Table 26.3). Observe old dressings for strikethrough (i.e., drainage on the outside of an old dressing) and then remove the dressing slowly, starting from the edges. If dressings adhere to the wound surface, moisten them with normal saline or water to reduce adherence and facilitate removal. If you can anticipate that there will be pain or if there is any pain during the removal process, before continuing start on preemptive anesthesia/analgesia until the patient is comfortable (discussed later in this chapter).

The surrounding skin, including contamination, maceration, signs of infection, and edema (Table 26.4).

The blood supply, particularly in lower extremity wounds (Table 26.5).

The frequently associated issues, for example, odor, pain, “woundedness,” anxiety, and depression (Table 26.6).

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury. Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared with the adjacent tissue. Evolution to a stage III or IV may be rapid.

Stage I. The heralding lesion of skin ulceration is nonblanchable erythema of intact skin usually over a bony prominence. In darker skin, the erythema may appear as persistent blue or purplish discoloration.

Stage II. Partial thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis, or both. The ulcer is superficial and looks like an abrasion, a shallow crater, or an open or ruptured blister.

Stage III. Full thickness skin loss involving subcutaneous tissue. The ulcer may extend down to, but not through, the underlying fascia. The ulcer looks like a deep crater, with or without undermining or tunneling of adjacent tissue (i.e., skin that overhangs wound edges).

Stage IV. The ulcer is deep enough to include necrosis and damage to underlying muscle, bone, and/or other supporting structures such as the tendon or joint capsule. Undermining of adjacent skin and sinus tracts or fistula is often present.

Unstageable, depth unknown.

Optimize nutritional status.

Start by reducing the interface pressure.

Prepare the wound bed. Cleanse, debride when there is necrotic tissue or slough with preemptive anesthesia/analgesia, and control infection and bleeding (24,25,26,27).

Dress the wound to promote moist interactive wound healing. If there is a risk of significant shearing, tearing, or regular contamination with exudate, urine, or stool that could cause maceration, protect surrounding skin.

Pack all dead spaces to keep them open and draining.

Layer dressings.

Finally, manage all associated issues, including pain, odors, and the patient’s “woundedness.”

Calories: provide 30 to 35 kcal/kg/d

Hydration: ensure adequate electrolyte-containing fluid intake noting that hypervolemia can delay healing. Strive for euvolemia

Protein: daily allowance of up to 1.5 g/kg/d may delay onset of pressure ulcers and promote healing

Vitamins: deficiency of vitamin C and zinc can delay healing, but there is little evidence to support routine supplementation. If diet is poor in fruits and vegetables and deficiency suspected or confirmed, offer a mineral and vitamin supplement.

Pressure reduction is a therapeutic strategy to reduce the interface pressure, not necessarily below capillary-closing pressure.

TABLE 26.3 Wound assessment | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a pressure-reducing surface, for example, air mattress or airbed. As patients approach death, the need for turning lessens as the risk of skin breakdown becomes less important.

TABLE 26.4 Surrounding skin assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|