Management of Pressure Ulcers and Fungating Wounds

Frank D. Ferris

Skin is one of the vital human organs. It has a highly developed physiology and several essential functions in the regulation of homeostasis and immunity.

Provides protection Skin surrounds virtually our entire bodies. It is the outer layer of the structures that hold us intact and give shape to our bodies. It also provides protection and a cushion when objects hit our bodies.

Senses environment Skin is highly innervated. It helps sense the environment and avoid injury. When skin is “wounded” and becomes inflamed or infected, the resulting inflammatory response can sensitize nociceptors, lead to recruitment of additional neurons, and increase neuronal firing of each involved neuron. Patients frequently experience increasing pain associated with the wound and the inflamed structures, that is, hyperalgesia and allodynia (1). Although opioid receptors are not present in normal skin, within minutes to hours of inflammation, they may appear in peripheral sensory nerves (2).

Maintains fluid balance Skin has a highly developed system of pores that help to control fluid balance. The pores open and close to regulate evaporation and transcutaneous perspiration.

Controls body temperature Skin also participates in the regulation of body temperature by releasing fluids on the surface as perspiration or sweat to evaporate and cool down the body.

Controls infection Intact skin presents a physical barrier to infections and immunologic barrier to infections. When skin is “wounded,” this barrier is broken and bacteria and other infective agents can colonize or infect the wound and the surrounding tissues and sometimes lead to systemic infections or even sepsis. Wound infections can secrete pathogens that inhibit epithelial cell mitosis and delay granulation and wound healing.

Creates body image Skin is the most visible organ. Its presence creates a bodily image of who we are. Disfigurement due to wounds may have profound consequences on an individual’s body image and the way others respond to her/him. If it is bad enough, the patient may want to withdraw, family members and friends may not want to look at the patient, and health care workers may not want to provide care. At a time when the patient may need more support than ever, she/he may be abandoned by family members and caregivers.

Creates body smells Skin secretes a number of fluids and substance that have associated smells. Over time, many people develop attractions to each other based on familiar scents. If those scents change or become overwhelmed by odors from putrefying tissues or infections, the effect may be repulsive and lead to isolation and abandonment.

There are multiple potential events that can damage skin integrity and/or function acutely or chronically. For patients with advanced cancer, particularly the elderly, pressure and fungating tumor masses are the most common causes of chronic wounds to the skin and the tissues that lie below it, that is, subcutaneous fat, muscles, bone, tendons, nerves, blood vessels, and so on.

When patients with cancer experience chronic wounds, not only do they suffer from the underlying cancer and their wounds, but their whole being is affected by the multiple physical, psychological, social, spiritual, practical, loss and end-of-life issues that are frequently associated with wounds. To be effective, care of such patients must be consistent with their goals of care and treatment priorities, and manage the whole “wounded” person, not just the “hole” (3, 4).

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure or decubitus ulcers are encountered frequently in patients with cancer, particularly those who are debilitated by their illness or by treatment (5, 6).

The microarterioles that supply blood to the skin run through the subcutaneous fat. In the face of mild pressure, the fat normally cushions and redistributes the pressure. However, when the pressure increases above the capillary filling pressure, the microarterioles close for as long as the pressure is present and the oxygen tension falls in the downstream tissues. Normal skin can withstand 30–60 minutes of poor perfusion but not longer. When the pressure and hypoxia are sustained, ischemia and necrosis can develop relatively rapidly (7, 8).

In both general hospital and long-term care, pressure ulcers occur in up to 28% of patients (9). One study of 980 home hospice patients found that 10% of patients developed ulcers during the study period (10).

Pressure points, for example, sacrum, heels, and elbows, are at particular risk for the development of ischemia and pressure

ulcers. Thin patients with cachexia who lack subcutaneous fat are even more susceptible. When they are weak, fatigued, and unable to move around by themselves, the risk of developing one or more pressure ulcers is very high. Shear, friction, prolonged presence of moisture associated with incontinence, age-related changes in skin, and poor nutrition further compound the risk (11).

ulcers. Thin patients with cachexia who lack subcutaneous fat are even more susceptible. When they are weak, fatigued, and unable to move around by themselves, the risk of developing one or more pressure ulcers is very high. Shear, friction, prolonged presence of moisture associated with incontinence, age-related changes in skin, and poor nutrition further compound the risk (11).

Pressure ulcers most often develop at body sites were the pressure is highest. In supine patients, 60% of pressure ulcers occur in the sacrum, and the greater trochanter and heel account for a further 15%. In patients who are constantly sitting, the ischial tuberosities are more susceptible (4).

Malignant Ulcers

Malignant wounds occur in up to 10% of patients with advanced or metastatic cancer, usually in the last 6 months of life (12). They can evolve from a primary tumor of skin or an invasive underlying mass, a recurrence along a surgical suture line, or a metastasis. They can be both erosive ulcers and/or expanding nodules. If many nodules confluence, the result can be a cauliflower-like wound. They are most commonly associated with cancers that start in the breast, particularly when they reoccur locally (50% or more). Other common sites include the head and neck (up to 30%) and axilla or groin (approximately 5%) (13, 14, 15).

Although a tumor initially stimulates neovascularization, a rapidly growing tumor can outstrip its available blood supply and necrose centrally. When the process involves the skin, it frequently becomes friable and produces significant exudate; becomes malodorous as the tissue putrefies and/or becomes infected with anaerobes; and frequently bleeds.

Assessment

In any patient with cancer who has developed a wound, or is at risk of developing one, start with a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s illness context, risk of developing a pressure ulcer, wound, surrounding skin, blood supply, frequently associated issues, for example, pain, odor, or “woundedness.”

Table 22.1 Context Assessment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Illness Context

Assess the context of the patient’s illness, including her/his cancer type, stage, and prognosis; functional status, for example, Karnofsky (KPS) or Palliative Performance Status (PPS); nutritional, fluid, and cognitive status; decision-making capacity; and goals of care (Table 22.1).

Pressure Ulcer Risk

The risk of developing a pressure ulcer increases as cancer advances, particularly when patients are debilitated (16).

Periodically assess every patient’s risk using either a Braden (17) (http://www.bradenscale.com/) or a Norton (18) risk assessment tool (http://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.table.4948). Both tools examine the most significant risk factors for developing a pressure ulcer including sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear (Table 22.2, a simplification of the Braden Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment tool—for complete details, refer to the original tool).

Periodically assess every patient’s risk using either a Braden (17) (http://www.bradenscale.com/) or a Norton (18) risk assessment tool (http://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.table.4948). Both tools examine the most significant risk factors for developing a pressure ulcer including sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear (Table 22.2, a simplification of the Braden Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment tool—for complete details, refer to the original tool).

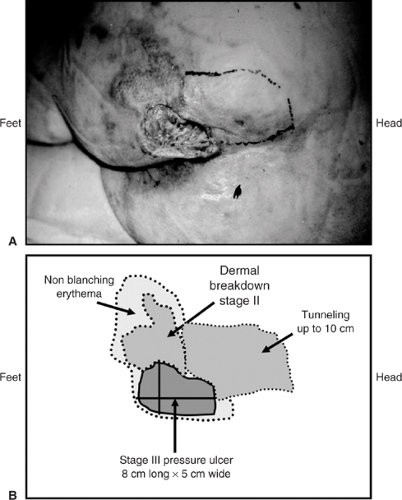

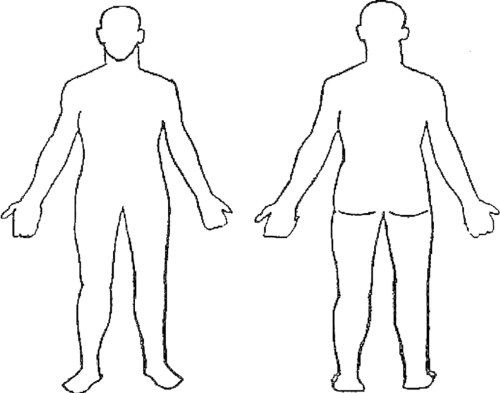

Figure 22.1. Wound location. Mark the location of each wound on the body diagrams. Label sites as A, B, C, D |

Table 22.2 Braden Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Once a wound develops, assess the following:

The wound, including the type (etiology), location (Figure 22.1), duration, description of the structure and base/surface, dimensions (best to document with a labeled photograph or diagram (Figure 22.2), exudate, and bleeding (Table 22.3). Observe old dressings for strikethrough (i.e., drainage on the outside of an old dressing) and then remove the dressing slowly, starting from the edges. If dressings adhere to the wound surface, moisten them with normal saline or water to reduce adherence and facilitate removal. If you can anticipate that there will be pain or if there is any pain during the removal process, before continuing start on preemptive anesthesia/analgesia until the patient is comfortable (discussed later in this chapter).

The surrounding skin, including contamination, maceration, signs of infection, and edema (Table 22.4).

The blood supply, particularly in lower extremity wounds (Table 22.5).

The frequently associated issues, for example, odor, pain, “woundedness,” anxiety, and depression (Table 22.6).

Staging

Pressure Ulcers

To help determine the management plan, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP/AHCPR) developed a system that is widely used to stage pressure ulcers (19).

Stage I The heralding lesion of skin ulceration is nonblanchable erythema of intact skin when compared with another region of the body. In darker skin, the erythema may appear as persistent blue or purplish discoloration.

Stage II Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis, or both. The ulcer is superficial and looks like an abrasion, a shallow crater, or a blister.

Stage III Full-thickness skin loss involving subcutaneous tissue. The ulcer may extend down to, but not through, the underlying fascia. The ulcer looks like a deep crater, with or without undermining of adjacent tissue (i.e., skin that overhangs wound edges).

Stage IV The ulcer is deep enough to include necrosis and damage to underlying muscle, bone, and/or other supporting structures such as the tendon or joint capsule.

Undermining of adjacent skin and sinus tracts or fistula may also be present.

Stage X Unstageable, depth unknown

Malignant Wounds

There is no specific staging system for malignant wounds.

Management

If patients who are at risk of developing a pressure ulcer, or those who are in the process of developing one, are caught early and appropriate prevention and treatment initiated, progression can be arrested and significant morbidity preempted.

Interdisciplinary

Wound care always involves an interdisciplinary team that includes a nurse and physician at a minimum, and may include an enterostomal therapist who is an expert in wound care, a pharmacist, a social worker, a chaplain, a physiotherapist, a dietitian, and so on, especially when the patient’s issues are more complex.

Establish Goals of Care

To develop an effective plan of care, start with effective communication with the patient or her/his surrogate decision maker about the context of the patient’s illness, the patient’s personal goals of care, and possible therapeutic options including their benefits and risks of harm and burden. Carefully guide a decision-making and treatment-planning process that involves the patient, her/his family, and caregivers.

For patients with pressure ulcers, if the blood supply to the surrounding tissues is adequate (i.e., Dorsalis pedis and/or posterior tibial pulses are palpable or ankle brachial index (ABI) >0.5 or toe arterial pressure >40 mm Hg), it may be possible to heal the wound. For many patients with advanced cancer and a short prognosis, it is unrealistic to strive to heal a pressure ulcer. For such patients, it is much more appropriate to focus on stabilizing the wound, relieving interface pressure to prevent further progression, and managing associated symptoms.

For patients with malignant wounds, if it is not possible to treat the underlying cancer, it will not be possible to heal a malignant wound.

Pressure Ulcers—When the Goal is to Heal

When the goal is to heal a pressure ulcer, management involves conventional wound care strategies (20).

Start by reducing the interface pressure.

Then prepare the wound bed. Cleanse, debride when there is necrotic tissue or slough with preemptive anaesthesia/analgesia, and control infection and bleeding (21, 22, 23, 24).

Once the wound bed has been prepared, dress the wound to promote moist interactive wound healing. If there is a risk of significant shearing, tearing, or regular contamination with exudate, urine or stool that could cause maceration, protect surrounding skin.

Pack all dead spaces to keep them open and draining.

Layer dressings.

Finally, manage all associated issues, including pain, odors, and the patient’s “woundedness.”

Table 22.3 Wound Assessment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reduce Interface Pressure

Continuous pressure, particularly over bony prominences, increases the risk of ischemia, skin breakdown, and pain (11). Pressure ulcers can develop within hours if the patient is not moved and circulation remains compromised.

Pressure at an interface is the force per unit area that acts perpendicularly between the body and the support surface. This parameter is affected by the stiffness of the support surface, the composition of the body tissue, and the geometry of the body being supported (16).

Table 22.4 Surrounding Skin Assessment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pressure reduction is a therapeutic strategy to reduce the interface pressure, not necessarily below capillary-closing pressure.

In patients with advanced cancer, particularly those who are debilitated, and patients with wounds, implement as many strategies to reduce, if not relieve, the interface pressure as much as possible, including repositioning, turning, massaging, supporting, protecting, and avoiding rolling and bunching of bedsheets and dressings.

Position

To minimize sacral pressure in patients who are bedridden, keep the head of the bed as low as possible, ideally at <30 degrees. Raise it only for short periods of social interaction or use foam wedges to support the patient. Avoid resting one limb on another. Use a pillow or another cushioning support to keep legs apart. Protect bony prominences with hydrocolloid dressings.

Turn

When a patient is unable to move by herself/himself, turn the patient from side to side every 1 to 1.5 hour. In addition to reducing pressure, this helps to relieve joint position fatigue in immobilized patients. Use a careful “log-roll” technique to distribute forces evenly across the patient’s body and minimize pain on movement. Use a draw sheet to reduce shearing forces that could lead to skin tears. If turning is painful, turn the patient less frequently and/or place the patient on a pressure-reducing surface, for example, air mattress or airbed. As patients approach death, the need for turning lessens as the risk of skin breakdown becomes less important.