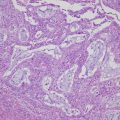

Fig. 16.2

Hypothesized molecular and physiological association with frailty [67], reprinted with permission of John Wiley and Sons

The question rises as to the best way of assessing elderly patients to determine if they are frail or not. Some useful criteria in this regard has been proposed based on the findings of the Cardiovascular Health Study, in which 5317 people aged 65–101 years (57.9% female, 14.8% African American) were evaluated to define the phenotype of frailty [68]. Five components of frailty were investigated, including unintentional weight loss (4.5 kg in the past year), weakness (grip strength, stratified by sex and body mass index), poor endurance (self-reported in response to two questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale [69]), slowness (walking speed, stratified by sex and height), and low physical activity (weighted score of kilocalories expended per week). Individuals who satisfied three or more of the above five criteria were defined as frail and those who met one or two criteria were categorized as pre-frail. Using these criteria, 368 people (6.9%) in this population were characterized as frail and 2480 (46.6%) as pre-frail. Mortality rates at 3 and 7 years in frail people were 18% and 43%, respectively, whereas those in non-frail people were 3 and 12%. This frailty phenotype could independently predict the risks of incident falls, worsened mobility or disability in activities of daily living, incident hospitalization, and death over 3 or 7 years, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.82 to 4.46 and from 1.28 to 2.10 for the frail and intermediate groups, respectively. Similar models of frailty have been proposed by the Women’s Health and Aging Study [70], the Edmonton Frail Scale [71], and others [72].

16.6.2 Pretreatment Evaluation in Elderly Patients

16.6.2.1 Score to Predict Peri-treatment Morbidities

Although medical frailty is a concept with a relatively short history, a frail state is clearly associated with poorer health outcomes in the elderly. Therefore, appropriate assessment of elderly patients is necessary to predict the risk of severe peri-treatment morbidities or an unexpected worse outcome when considering treatment for any type of cancer. Several systematic reviews have revealed that appropriate assessment has adequate feasibility and high sensitivity for predicting frailty in elderly patients with cancer. However, the types of assessment used have not always been useful for prediction of adverse outcomes or had high specificity or negative predictive value [73–75]. Therefore, it is possible that the assessment methods presently used to guide therapeutic decision-making may be inadequate for elderly patients with cancer.

16.6.2.2 Assessment to Predict Perioperative Morbidities

Efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of the assessment protocols proposed for elderly patients with ovarian cancer are ongoing. The Modified Frailty Index (mFI) consists of 11 variables derived from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Frailty Index and was reported to predict morbidities requiring ICU admission in patients scheduled for colectomy (Table 16.1) [76]. The usefulness of the mFI as a predictor of the risk of morbidities has also been investigated in a retrospective study of 6551 patients who were identified in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data for 2008–2011 as having undergone surgery for gynecologic cancer (although the exact number with ovarian cancer was not reported) [77]. One hundred and eighty-eight (2.9%) of these women developed life-threatening complications requiring management in ICU or resulting in death within 30 days postoperatively. The complication rates were 2, 2.7, 4.4, 7.4, and 24.4% for mFI scores of 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥4, respectively, and were significantly higher in patients with a score ≥ 3 than those with a score ≤ 2 (P < 0.001). In multivariate analysis, significant predictors of severe complications were a preoperative albumin level < 3 g/dl (OR 6.5, 95% CI 4.31–9.96), longer operating time (OR 1.003 per minute increase, 95% CI 1.001–1.004), non-laparoscopic surgery (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.56–8.83), and an mFI score ≥ 2 (score 2, OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.17–3.11; score 3, OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.05–5.19; score ≥ 4, OR 12.5, 95% CI 4.77–32.76). When the women were categorized as low-risk and high-risk groups on the basis of a preoperative albumin level ≤ 3 g/dl and/or an mFI score ≥ 4, the high-risk group showed a higher (≥10%) rate of severe perioperative complications when compared with the low-risk group (≤10%). The authors concluded that the mFI criteria could identify patients with gynecologic malignancy who were at high risk for perioperative complications that require management in ICU or are fatal.

Variables for Modified Frailty Index (mFI) | |

|---|---|

1. | Nonindependent functional status |

2. | History of diabetes mellitus |

3. | History of either chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pneumonia |

4. | History of congestive heart failure |

5. | History of myocardial infarction |

6. | History of percutaneous coronary intervention, cardiac surgery, or angina |

7. | Hypertension requiring the use of medications |

8. | Peripheral vascular disease or rest pain |

9. | Impaired sensorium |

10. | Transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular accident without deficit |

11. | Cerebrovascular accident with deficit |

An ovarian cancer-specific investigation has since been performed for 751 patients aged ≥65 years identified in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database as having undergone PCS between 2005 and 2016 [78]. One hundred and twenty-three (16.4%) of these patients encountered complications of the same level of severity as those described in the previous report [77]. A number of variables, including patient demographics (age, body mass index, race), preoperative laboratory values (creatinine, hematocrit, platelet count, white blood cell count, albumin), and comorbidities (hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction within the previous 6 months, history of transient ischemic attack), were compared between patients with and without severe morbidities. Eight variables identified to be significant were chosen for a model to predict the probability of postoperative complications in patients aged ≥65 years undergoing PCS for ovarian cancer (Table.16.2). The variables chosen for the proposed predictive model were ascites (present or absent), current smoking (yes or no), race (white vs. nonwhite), preoperative creatinine (≥1.5 mg/dL or <1.5 mg/dL), preoperative platelet count (≥450 × 109/L or <450 × 109/L), preoperative hematocrit (≥30% or <30%), preoperative white blood cell count (≥10 × 109/L or <10 × 109/L), and preoperative albumin (≥3.5 g/dL or <3.5 g/dL). The area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve for the model was 0.725, indicating fair (not poor but not good) performance. This model could predict a 35% probability of severe postoperative complications with 21.8% sensitivity and 92.6% specificity. When the threshold of prediction was decreased to 50% probability, the sensitivity decreased to 9.8% although specificity increased to 98.0%. These findings indicate that preoperative evaluation to identify patients with the highest risk of severe postoperative complications is not easy. However, the high specificity of this model means that patients who can undergo PCS safely could be identified, including those who are elderly.

Variables for the predictive model | |

Physical status or habit | |

Ascites | Yes or No |

Current smoker | Yes or No |

Race | White or Non-white |

Preoperative laboratory data | |

Creatinine (mg/dL) | <1.5 or ≥1.5 |

Platelet (×109/L) | <450 or ≥450 |

Hematocrit (%) | <30 or ≥30 |

White blood cell (×109/L) | <10 or ≥10 |

Albumin (g/dL) | <3.5 or ≥3.5 |

16.6.2.3 Assessment to Predict Tolerance of Chemotherapy

A GINECO study has reported a comprehensive geriatric assessment tool that can predict the risk of severe treatment-related toxicities in elderly patients with ovarian cancer [23]. Based on their study findings, the authors devised a geriatric vulnerability score (GVS), calculated from five criteria, namely, a low activities of daily living score (<6), a low instrumental activities of daily living score (<25), hypoalbuminemia (<3.5 g/dL), lymphopenia at inclusion (<1 × 109/L), and a high Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score (>14). GVS is sum of these variables of each patient. The patients aged ≥70 years with ovarian cancer were separated into two groups using a cutoff point of 3. Patients with a GVS ≥3 were significantly less likely to complete their planned chemotherapy than those with a GVS <3 (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.17–0.99; P = 0.044) and were significantly more likely to have more severe (grade ≥ 3) non-hematologic toxicities (OR 4.40; 95% CI 1.92–10.08; P = 0.0002), more serious adverse events (OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.27–6.11; P = 0.009), and more unplanned hospital admissions (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.17–5.63; P = 0.017) [79]. Since the chemotherapy administered in this study was carboplatin alone, further investigation is needed to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the GVS in elderly patients with ovarian cancer who receive combination chemotherapy with a taxane and a platinum agent.

Conclusion

Nearly half of all patients with ovarian cancer are diagnosed in the advanced stages of the disease and have peritoneal carcinomatosis at this time. The mainstay of treatment for advanced ovarian cancer continues to be maximal PCS followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Clearly, the improvements in supportive care for patients and in the surgical devices available, as well as innovative cytotoxic and supportive agents, have contributed to the improved treatment of ovarian cancer. However, it should be acknowledged that the development of clinical guidelines has played a very important part in these improvements. Clinical evidence concerning the treatment of various types of cancer in the elderly has been steadily accumulating in recent years, and general guidelines for geriatric medicine have been proposed [80–82]. However, guidelines specific for the treatment of each type of cancer have not been adequately developed for elderly patients because of the difficulties inherent in performing clinical trials in this age group. Therefore, our treatment strategies for these patients have to be based on relatively limited evidence from analyses of subgroups in the major clinical trials.

The current evidence indicates that every effort should be made to perform PCS followed by chemotherapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, regardless of the patient’s chronological age. A weekly chemotherapeutic regimen or single-agent chemotherapy is recommended for elderly patients and those with poorer performance status. However, the issues of frailty and the higher risk of peri-treatment morbidities do need to be considered in these patients. There is increasing awareness of the importance of appropriate assessment of geriatric patients with cancer, and a variety of scoring systems to predict the risks of treatment have been proposed.

It is now time to leave behind the concept that elderly patients are only eligible for palliative treatment because of their chronological age. Further studies, based on the accumulation of evidence from clinical trials that have included elderly patients, will be invaluable for increasing the reliability of geriatric assessment protocols and for predicting patients who can tolerate standard treatments.

References

1.

Surveillance, Epidemiologyand End Results Program. National Cancer Institute, Rockville, 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html Accessed 10 Dec 2016.

2.

3.

World Health Organization. Definition of an older or elderly person. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/ Accessed 10 Dec 2016.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Thrall MM, Goff BA, Symons RG, Flum DR, Gray HJ. Thirty-day mortality after primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian cancer in the elderly. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:537–47.CrossrefPubMedPubMedCentral

9.

10.

11.

12.

Patankar S, Burke WM, Hou JY, Tergas AI, Huang Y, Ananth CV, et al. Risk stratification and outcomes of women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:62–9.CrossrefPubMedPubMedCentral

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree