Management of Advanced Heart Failure

Rodney Tucker

Barry K. Rayburn

Heart failure is a chronic illness that is increasing in frequency and considered to be a major public health problem in the United States. It is primarily defined as a syndrome caused by the overall inadequate performance of the heart, leading to a constellation of clinical symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, and swelling among others. The pathophysiology of heart failure involves a complex series of structural, functional, and biochemical events that are responsible for the overall progressive nature of the disease. The term advanced heart failure is most commonly used to describe symptomatic patients who have progressed to New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class IV or American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Stage D as described in this chapter and are receiving maximum medical therapies. The NYHA Class is based solely on symptoms with Class IV patients typically having heart failure symptoms at rest. The AHA/ACC Staging system, on the other hand, is based on stages of disease progression ranging from patients at potential risk for heart failure (Stage A) through patients with advanced heart failure, refractory to standard medical management (Stage D). Heart failure is responsible for most hospital admissions among the elderly and is one of the leading costs in the Medicare system. In addition, advanced heart failure has a worse prognosis than many cancers, with a one year mortality approximating 45% (1).

This chapter provides the basic epidemiology, pathophysiology, and natural history of heart failure with an emphasis on the advanced state. The rationale and complexity of the overall treatment is outlined, including pharmacotherapy as well as device therapy. The role of expanded services in supportive and palliative care as well as the role of the palliative medicine specialist as part of the care team is reviewed. Communication challenges that exist in caring for patients with an uncertain disease trajectory and the role of hospice as an option for care for patients with end-stage disease are highlighted.

Epidemiology

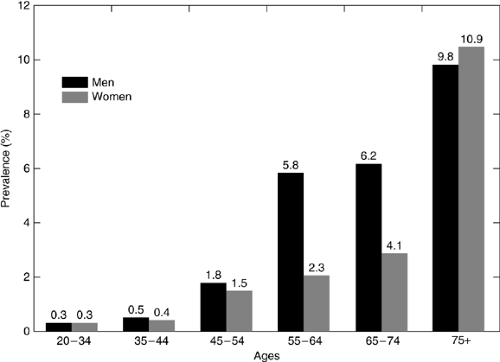

Despite substantial advances in the therapy for heart failure, it remains a common, morbid, and mortal condition. Current estimates suggest that approximately 5 million Americans suffer from heart failure with new cases being diagnosed at a rate of 550,000 per year (2). Both the incidence and prevalence figures are likely to continue to increase with estimates of an annual incidence of 800,000 by 2010 (3). Although improved survival from myocardial infarction has contributed in part to this rather dramatic increase in prevalent cases, this increase can be attributed chiefly to the “graying” of the American population. Heart failure disproportionately affects the elderly with the prevalence rising with each decade of life (Fig. 30.1). Between 1990 and 2000, the number of Americans aged 60 or over increased by 3.9 million with individuals over 85 years of age accounting for 1.1 million (4). Heart failure morbidity includes diminished functional capacity, complex drug regimens, and, for many patients with advanced heart failure, frequent hospitalizations. Cowie et al. studied hospitalizations in a community-based population and found that 59% of patients diagnosed with heart failure were admitted during the 19-month average follow-up period with many patients admitted multiple times (5). Heart failure mortality figures also remain high despite improvements in therapy. An important reality in the management of heart failure is that most of the patients with this diagnosis will ultimately die of it (6). Gross mortality estimates for patients with heart failure vary depending on a number of variables including demographic factors, comorbidities, underlying etiology, functional status, hemodynamic variables, and response to therapy. For example, severely symptomatic patients (NYHA Class IV) with an ischemic etiology and persistent elevation of right atrial pressure despite optimal medical management may have an annual mortality approaching 50%, whereas a relatively asymptomatic patient (NYHA Class I) with diastolic dysfunction due to underlying hypertension that is now controlled may have a mortality comparable to the general population with hypertension (7, 8). In the context of this chapter, patients with “advanced” heart failure, by definition, are patients with a very high anticipated mortality. Although various models are available to predict mortality rates for individuals, such models often fail to accurately identify which patients with a specific set of characteristics are likely to die (9). Because of this difficulty, patients with heart failure are frequent “graduates” of hospice programs.

Pathophysiology

The functional definition of heart failure is a clinical syndrome in which the heart is unable to meet the metabolic needs of the body (10). Several points are important in fully understanding this definition. First, heart failure is not a specific disease, but rather a clinical syndrome that results from any of a number of underlying diseases. An individual may recover from heart failure, although the underlying disease may still be present. Second, the definition of heart failure does not specify that the heart is weak. In fact, most cases of heart failure are the result of a combination of systolic and diastolic dysfunction, with

the latter predominating in up to 50% of the cases (8). Third, this definition avoids the term “congestive” because not all the manifestations of heart failure require congestion—or volume overload. Much of the symptom burden of heart failure results from a low cardiac output state.

the latter predominating in up to 50% of the cases (8). Third, this definition avoids the term “congestive” because not all the manifestations of heart failure require congestion—or volume overload. Much of the symptom burden of heart failure results from a low cardiac output state.

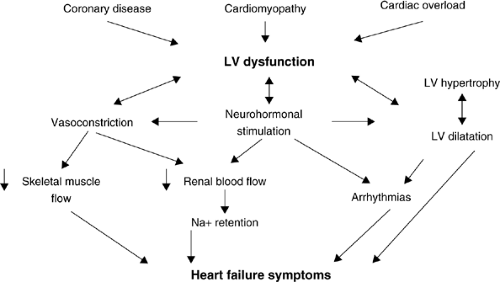

There are two major pathophysiologic models that exist to explain the clinical manifestations of heart failure. The first and older of the two is a hydraulic model, which explains the relationships between flow and pressure in the cardiovascular system. Regardless of the predominance of systolic or diastolic dysfunction, an abnormal relationship between pressure and flow can result in elevated filling pressures on the right or left side of the heart coupled with low forward flow due to reduced contractility for any given filling pressure. The former phenomenon manifests as the congestive symptoms of edema, orthopnea, early satiety, and dyspnea, whereas the latter will manifest as fatigue, depression, anorexia, and also dyspnea due to muscle fatigue and inefficiency. Although this model explains most of the symptoms of heart failure well, and can be used to model treatments such as diuresis and after-load reduction, it falls short of explaining the progressive nature of the syndrome and the high mortality despite the above-mentioned treatments. A more comprehensive model that has evolved and resulted in dramatic improvements in therapy is the neurohormonal model of heart failure. The central hypothesis of the neurohormonal model is that the hydraulic manifestations of heart failure lead to stimulation of various compensatory mechanisms that, in turn, are deleterious to cardiac function (Fig. 30.2). This model explains the relentlessly progressive nature of heart failure and has led to the development of several effective therapies as discussed in the following text. Besides neurohormones, other circulating factors such as inflammatory cytokines are involved in the clinical manifestations of heart failure and are included in this hypothesis.

Virtually any cardiac disease can ultimately result in heart failure. In the United States, the most common cause of heart

failure is coronary artery disease (11). Coronary disease may result in profound ventricular dysfunction through permanent loss of myocardium as in an infarct or through ischemia, a potentially reversible condition. Cardiomyopathies, hypertension, valvular heart disease, and congenital abnormalities account for the bulk of the remaining cases.

failure is coronary artery disease (11). Coronary disease may result in profound ventricular dysfunction through permanent loss of myocardium as in an infarct or through ischemia, a potentially reversible condition. Cardiomyopathies, hypertension, valvular heart disease, and congenital abnormalities account for the bulk of the remaining cases.

Natural History and Prognosis

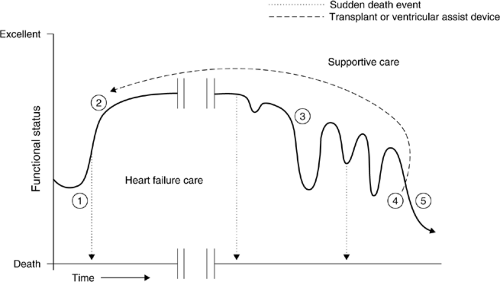

As discussed in the preceding text, the mortality of heart failure remains high with advanced stage patients accounting for up to 50% annual mortality. Despite these rather ominous survival statistics, the clinical course of heart failure can be very protracted. A rather typical clinical course for an individual patient is illustrated in Figure 30.3. Patients are usually diagnosed with at least moderate symptoms. Following initiation of therapy, many patients improve significantly, and this improvement may be expected to last for a variable period of time. In some patients, this “plateau” of stability may be short-lived and in others it may continue for many years. In most of the patients, this stable phase will ultimately give way to a period of intermittent exacerbations characterized by frequent physician visits, changes in medical therapy, and hospitalizations. Although individual exacerbations may improve, the overall trend tends to be downhill with the time interval between exacerbations becoming shorter. Without further intervention, this course will ultimately lead to death from pump failure. Interventions at this advanced stage may temporarily reset the patient back onto a plateau, but will eventually lead to the same deterioration for most. For some patients, arrhythmias intercede in this clinical course, often at the earlier, less symptomatic stages, and result in sudden cardiac death. This latter phenomenon has led to the increased utilization of implantable defibrillators, which, in turn, may shift the mode of death toward progressive pump failure. The combination of a progressive natural history leading to death from pump failure and the unexpected possibility of sudden cardiac death at any point suggests that the role of supportive care should ideally begin early in the patient’s clinical course. Data from the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT) trial further support this idea (12). In this trial, over 1400 patients with heart failure were followed up. Thirty-eight percent died within the first year of follow-up. Clinicians caring for these patients estimated their 6-month survival at greater than 50% up to 3 days before their death. Therefore, the concept of using prognostic criteria to decide when to initiate supportive care may be flawed. End-of-life care is more typically provided to patients who have entered the downhill phase of their clinical course and have exhausted or opted out of therapies that could potentially return them to clinical stability. Such patients are usually characterized by NYHA Class III or IV symptoms and are in ACC/AHA Stage D.

Heart Failure Therapy

Overview

Modern therapy for heart failure is a multifaceted approach to a complex clinical syndrome (Table 30.1). Therapy consists of education, pharmacotherapy, and for an increasing percentage of patients the use of electrical and mechanical devices. Education and basic pharmacotherapy provide the foundation upon which other therapeutic options are added in an individualized fashion. Our improved understanding of the pathophysiology of heart failure has led to comparable improvements in pharmacologic therapy. Most of the data regarding the treatment of heart failure have been obtained from patients in whom systolic dysfunction predominates. Fewer data exist for patients with primarily diastolic dysfunction. Where such data exist, they will be discussed but to a large extent the clinician is left with principles of management rather than specific data in managing patients with diastolic dysfunction.

Table 30.1 Heart Failure Therapya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Despite excellent data and rationale for various therapies in heart failure, an alarming number of patients are inadequately managed by either underutilization or, less commonly, overutilization of various therapies (13, 14). This fact is significant for

the palliative care practitioner because of the possibility of patients being referred for end-of-life care whereas they may have significant therapeutic options. Data show that patients followed up by a physician specializing in the care of heart failure are more likely to be treated according to evidence-based guidelines than patients followed up by other specialists or by generalists (15, 16). A patient referred for end-of-life care may warrant review by such a specialist, if available, to confirm the lack of therapeutic options.

the palliative care practitioner because of the possibility of patients being referred for end-of-life care whereas they may have significant therapeutic options. Data show that patients followed up by a physician specializing in the care of heart failure are more likely to be treated according to evidence-based guidelines than patients followed up by other specialists or by generalists (15, 16). A patient referred for end-of-life care may warrant review by such a specialist, if available, to confirm the lack of therapeutic options.

Patient Education

All patients with heart failure should be educated as an integral part of their management. The specific role of disease management programs is discussed later in this chapter, but basic education is essential for all patients. Since volume management is a common problem in heart failure, all patients should be placed on a sodium-restricted diet. A typical limit is between 2 and 4 g of sodium per day. Fluid restrictions are also often employed, especially for patients with advanced heart failure or those suffering from hyponatremia. Weighing daily helps to monitor sudden changes in fluid volume, thus allowing for changes to be made in therapy before clinical symptoms worsen. Patients should also be encouraged to avoid certain types of medications—both prescription and over-the-counter. Decongestants can promote cardiac dysrhythmias in this susceptible population and should be avoided in most situations. The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, by their nature, can lead to a reduction in renal blood flow, resulting in decreased response to diuretics and marked sodium retention. This phenomenon can happen with virtually all drugs in this class, including the newer cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors (17).

Pharmacotherapy

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Activation of the renin-angiotensin system is a central feature in heart failure. This activation results in elevated levels of angiotensin II, which in turn causes vasoconstriction, sodium and water retention, and adverse cardiac remodeling (10). Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, resulting in decreased levels of the latter in patients with heart failure. Multiple randomized clinical trials in patients ranging from NYHA Class IV to patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction have demonstrated improved patient outcomes with the use of ACE inhibitors (18). The use of ACE inhibitor may be limited by profound hypotension (although relative hypotension is common and often desirable in patients with heart failure), allergies to this class of medicines, and commonly a dry, persistent cough.

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers

Alternate pathways for the production of angiotensin II exist, resulting in accumulation even in the presence of ACE inhibition. The development of angiotensin II receptor blockers allows for blockade at the level of the receptor. Studies on patients with heart failure have produced variable results, but overall suggest that the use of a receptor blocker as an alternate to an ACE inhibitor is likely comparable for most patients (10). Data do not yet support the routine use of this class of drug in addition to ACE inhibition and the weight of evidence still favors ACE inhibition as first-line therapy for tolerant patients. A major, significant trial of angiotensin II receptor blockade in patients with diastolic dysfunction (CHARM-Preserved) demonstrated a reduction in hospitalization but no change in mortality when compared with placebo (19).

β-Adrenergic Blockers

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree