Richard G. Stefanacci, Jill L. Cantelmo

Managed Care for Older Americans

Managed care is thought by many to be the answer to the question of how to improve access to, and the quality and cost of, health care for older Americans. This is an especially critical issue given the number of aging baby boomers and the increasing availability of expensive new diagnostics and treatments, all in the context of limited Medicare resources.

In response to these significant challenges, Medicare and others are turning to managed care. Specifically, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is moving from the use of traditional Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) programs, which are still used by about 70% of Medicare beneficiaries, to managed care within Medicare. Medicare managed care differs from FFS in the types of delivery and payment models utilized, and it offers more opportunities to increase the quality of care provided to patients while aligning financial incentives more closely with the quality of care, as opposed to the volume of services, provided.1,2 The traditional FFS model is increasingly believed to contribute to suboptimal health care quality and higher costs because it encourages providers to use more—and potentially more expensive—services without any link to quality of care, patient outcomes, or coordination of care.2

Conversely, a managed care system aims to deliver value (i.e., quality tied to the investment in cost) through access to quality, cost-effective health care.3 In its broadest sense, managed care refers to a system where a payment is made to a provider or health plan that is then responsible for a group of services. A more traditional and focused view of managed care refers only to health plans that are responsible for providing all of the services available under the entire Medicare program, with the exception of hospice services. These services can be provided either directly through a closed system of providers or through an open system using contracted community providers. The closed system uses a full complement of employed providers. Medicare managed care plans, referred to as Medicare Advantage (MA), were established by the CMS in 2003 as part of the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA). Prior to 2003, these plans, which fell under Medicare Part C, were referred to as Medicare+Choice or simply as a health maintenance organization (HMO).

Medicare managed care plans have several potential advantages over the traditional Medicare FFS program. These advantages include lower deductibles and co-payments, as well as benefits that are not part of Medicare FFS coverage, such as payments for preventive care, including reimbursement for eyeglasses and hearing aids; health education; and health promotion programs such as case management and disease management. Managed care plans can also provide discounts on, or improved access to, transportation, day care, respite care, or assisted living. MA plans are also not restricted by Medicare FFS rules such as the requirement for 3 hospital days plus a discharge day to qualify for subacute services. Instead, MA plans can admit members directly to skilled nursing facilities, thus avoiding hospitalizations and their associated costs, both financial and health-related. This subacute level of care is for services requiring skilled nursing care, such as intravenous therapy or rehabilitation.

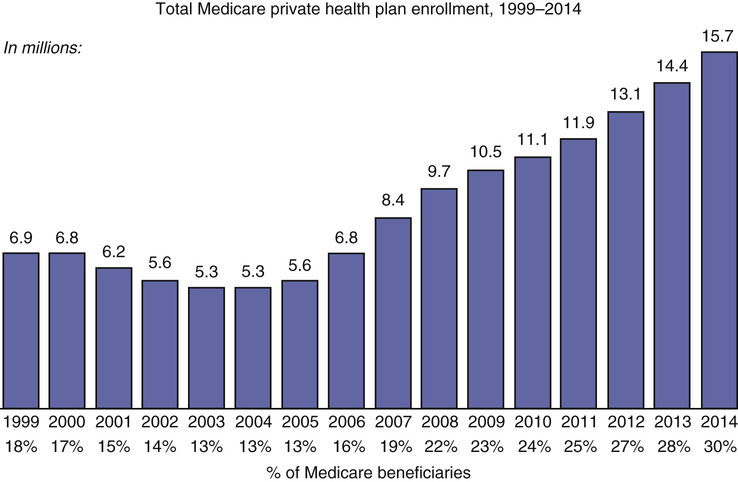

The important benefits that MA plans offer over traditional Medicare FFS have led to increasing enrollment; 30% of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in an MA plan as of March 2014.4 The number of MA plans offered is substantial, with the average urban- or suburban-dwelling beneficiary having a choice of approximately 20 plans and rurally located beneficiaries having about 11 plans to choose from. The average unweighted premium for an MA plan in 2014 was $49. This is far below the Medicare FFS premium, which was estimated to be $140.90 for Part B in 20164a and does not include the supplemental insurance, Medigap, that many FFS beneficiaries add on to cover other costs (e.g., catastrophic hospital expenses) and which adds an additional average of $183 to their premiums.5

Although coverage for pharmaceutical costs has historically been a major reason why older adults have enrolled in Medicare managed care, the introduction of free-standing prescription drug plans under Medicare Part D, which started January 1, 2006, removed this differential from FFS in traditional Medicare. As a result of Medicare Part D, both Medicare FFS and Medicare managed care plans provide the opportunity for coverage of prescription medications.

Thus, principles of managed care are moving beyond MA plans and are increasingly being introduced into portions of Medicare FFS through such programs as pay-for-performance and various delivery and payment reform models. Medicare is applying the principles of managed care so older adults in traditional Medicare can also benefit.

Managed Care Timeline

The modern era of managed care was heralded by a new law enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1974. This law permitted the establishment of HMOs, whose purpose was to encourage the development of prepaid health plans. From the mid-1970s until the late 1990s, managed care saw a slow and consistent growth. Participation in Medicare managed care increased steadily in the 1990s, reaching a peak of 6.3 million beneficiaries (16%) in 2000.

In 1997, revisions enacted by Congress that increased administrative burden and reduced payments to the health plans resulted in many plans exiting the market or limiting their enrollment.4 Enrollment declined between 2000 and 2003 because of plan withdrawals from some areas, reduced benefits, and higher premiums.

A rebirth of managed care for Medicare beneficiaries occurred in 2003 with the passing of the MMA, which established MA and added different managed care options such as demonstration programs and special needs plans (SNPs). The MMA also increased payments to MA plans, which were used to raise payments to providers, decrease enrollee premiums, enhance existing benefits, and increase stabilization funds. As a result of these changes, enrollment in MA plans rose slightly from 2003 to 2004 and has steadily increased each year since, with 15.7 million Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in 20145 (Figure 129-1).

As part of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), reductions in the rates that CMS pays for MA plans were proposed in order to bring them more in line with the rates paid in traditional Medicare. The proposed cuts caused a backlash among insurers, who stated that the reduction in rates would lead to fewer plan options and increases in premiums for seniors to make up for the differences. Despite rate reductions introduced in 2013, enrollment in MA plans continued to increase, rising 9%.6 In April 2014, CMS reversed its plan to implement further cuts to MA plan rates and actually increased these by 0.4%, citing changes in risk factor assessments for plans, a decrease in spending for Medicare health services, and changes to plans’ payment formulas.7

Today, Medicare managed care exists beyond traditional MA plans through delivery models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), the patient-centered medical home (PCMH), and bundled payments arrangements. These and other models force the application of managed care principles to improve health outcomes for older Americans in addition to increasing access and quality and decreasing costs.

Many of these new models are being developed and tested under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovations. The Innovation Center was created by Congress for the purpose of testing “innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures …while preserving or enhancing the quality of care” for those individuals who receive Medicare, Medicaid, or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) benefits.

The Innovation Center is currently focused on the following priorities:

• Testing new payment and service delivery models

• Evaluating results and advancing best practices

• Engaging a broad range of stakeholders to develop additional models for testing

Congress provided the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services with the authority to expand the scope and duration of a model being tested through rulemaking, including the option of testing on a nationwide basis. In order for the Secretary to exercise this authority, a model must either reduce spending without reducing the quality of care or improve the quality of care without increasing spending, and it must not deny or limit the coverage or provision of any benefits. These determinations are made based on evaluations performed by the CMS and the certification of CMS’s Chief Actuary with respect to spending.

Some of the Innovation Center models being tested include the following.

• Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Care Initiative

• Medicare Health Care Quality Demonstration

• Nursing Home Value-Based Purchasing Demonstration

• Physician Group Practice Transition Demonstration

• For-Profit Demo Project for the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE)

• Rural Community Hospital Demonstration

• Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Model 1: Retrospective Acute Care Hospital Stay Only

• BPCI Model 2: Retrospective Acute and Post-Acute Care Episode

• BPCI Model 3: Retrospective Post-Acute Care Only

In BPCI model 3, retrospective bundled payments are made for post-acute care only.

• BPCI Model 4: Prospective Acute Care Hospital Stay Only

In BPCI model 4, prospective bundled payments are made for acute care hospital stays only.

• BPCI Medicare Acute Care Episode Demonstration

• BPCI Medicare Hospital Gainsharing Demonstration

• BPCI Physician Hospital Collaboration Demonstration

• BPCI Specialty Practitioner Payment Model Opportunities: General Information

• Primary Care Transformation: Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative

• Primary Care Transformation: Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration

• Primary Care Transformation: Graduate Nurse Education Demonstration

• Primary Care Transformation: Independence at Home Demonstration

• Primary Care Transformation: Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration

• Primary Care Transformation: Multi-payer Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration

• Primary Care Transformation: Transforming Clinical Practices Initiative

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicaid and CHIP Population: Medicaid Emergency Psychiatric Demonstration

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicaid and CHIP Population: Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases Model

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicaid and CHIP Population: Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative: Effort to Reduce Early Elective Deliveries

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicaid and CHIP Population: Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative: Enhanced Prenatal Care Models

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicaid and CHIP Population: Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative: General Information

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees: Financial Alignment Initiative for Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees

• Initiatives Focused on the Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees: Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations Among Nursing Facility Residents

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: Frontier Community Health Integration Project Demonstration

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: Health Care Innovation Awards

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: Health Care Innovation Awards Round Two

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: Maryland All-Payer Model

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: Medicare Care Choices Model

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: Medicare Intravenous Immune Globulin Demonstration

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: State Innovation Models Initiative: General Information

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: State Innovation Models Initiative: Model Pre-testing Awards

• Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models: State Innovation Models Initiative: Model Testing Awards

• Initiatives to Speed the Adoption of Best Practices: Community-Based Care Transitions Program

• Initiatives to Speed the Adoption of Best Practices: Innovation Advisors Program

• Initiatives to Speed the Adoption of Best Practices: Medicare Imaging Demonstration

• Initiatives to Speed the Adoption of Best Practices: Million Hearts

Million Hearts is a national initiative to prevent 1 million heart attacks and strokes over 5 years.

• Initiatives to Speed the Adoption of Best Practices: Partnership for Patients

Medicare Managed Care Under Fee-for-Service

Of course, several of these and previous attempts to manage Medicare were applied within the Medicare FFS model. Under the Medicare Part A benefit, also referred to as hospital insurance, providers are paid a defined amount for providing a bundle of services. Medicare Part A providers include acute care hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, subacute care, and hospice. It is important to note that while Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) includes Medicare Part A, Part B, and in most cases Part D, hospice is still provided as a separate benefit. Because Medicare Part A providers are paid a capitated payment, they are encouraged to use managed care principles to control cost and improve outcomes.

Medicare Part B, also known as medical insurance, covers physician provider services. Although, historically, these services were paid simply on the basis of the number and type of services provided, CMS is applying managed care principles to this program, as well. The 2006 Tax Relief and Health Care Act required the establishment of a physician quality reporting system, including an incentive payment for eligible professionals who satisfactorily report quality measure data for covered services furnished to Medicare beneficiaries. CMS named this program the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), which by 2008 consisted of 119 quality measures and 2 structural measures—one related to whether a professional has and uses electronic health records and the other related to the use of electronic prescribing.8 The PQRI was included as a key voluntary Medicare physician quality reporting system in the PPACA, with extension of the incentive payment program through 2014 for eligible practitioners who submit quality measure data and implementation of penalties in 2015 for all Medicare providers who fail to participate in the program. In 2011, the program underwent a name change, becoming the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). Participation in the PQRS allows Medicare physicians to apply the use of managed care principles to the Medicare FFS program by assessing the quality of care they are providing to their patients, tracking their performance on various quality metrics, and enabling comparison of their performance with that of their peers.9

Prescription drug plans, as previously mentioned, are authorized under the Medicare Part D program. In addition to general managed care principles to ensure appropriate medication use, prescription plans are required by CMS to provide medication therapy management (MTM) programs.10 CMS’s objectives with regard to MTM programs, which are provided by pharmacists and other qualified providers, are to control costs and improve quality and outcomes through optimized medication use and reduction in the risk of adverse drug events.10 MTM programs were expanded as part of the PPACA, in part to increase the consistency with regard to Medicare beneficiaries’ eligibility for MTM programs. Currently, Part D enrollees who have two or more chronic diseases must be targeted for MTM, and the following disease states must specifically be targeted: hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, respiratory disease, bone diseases and arthritis, and mental health diseases. Additionally, those beneficiaries who are taking multiple Part D drugs and are likely to incur annual costs for covered Part D drugs exceeding a predetermined level are targeted for MTM programs.11,12

Chronic illnesses, such as heart disease and diabetes, are a major detriment to beneficiaries’ quality of life, and care for these beneficiaries is a major expense to the Medicare program. Furthermore, the number of beneficiaries who have multiple chronic illnesses is increasing dramatically. The proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with five or more chronic conditions increased from 30% in 1987 to 50% in 2002.13 Having multiple chronic illnesses compounds the complexity and cost of care required, impacting beneficiaries’ ability to perform regular activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, eating, and dressing), increasing rates of hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, and leading to longer lengths of stay.13,14 Recent data show that almost half of the total of Medicare spending is attributable to the 14% of beneficiaries who have six or more chronic conditions.14 Coordinating the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions is also a challenge for various reasons, including an increasing number of treating physicians (ranging from 4 physicians for a patient with one condition to 14 physicians for a patient with five or more conditions) and polypharmacy, and the related impact on adherence, compliance, and adverse drug events (such as drug-drug interactions).12

The CMS conducts and sponsors a number of innovative demonstration projects to test and measure the effect of potential program changes. The CMS demonstrations study the likely impact that new methods of service delivery, coverage of new types of service, and new payment approaches have on beneficiaries, providers, health plans, states, and the Medicare Trust Funds. Evaluation projects validate CMS research and demonstration findings and help CMS monitor the effectiveness of Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Many of the demonstration projects are focused on managing care for those Medicare beneficiaries suffering from chronic illnesses. The following are examples of some of the many demonstration projects that CMS has funded in the past and continues to fund.

Independence at Home Demonstration15

The Independence at Home Demonstration was created to test the effectiveness of medical practices in delivering comprehensive primary care services at home and to assess whether this delivery model improves care for Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions. The demonstration will also examine the impact of home-based care on hospitalization needs, patient and caregiver satisfaction, and Medicare costs. Providers will be rewarded for demonstrating improved care and lowered costs.

Community-Based Care Transitions Program16

This demonstration was established to test models for improving transitions of Medicare beneficiaries from the inpatient hospital setting to other care settings, to improve care quality, and to reduce readmissions for high-risk beneficiaries.

Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care Initiative17

The Comprehensive ESRD Care initiative was established to identify, test, and evaluate approaches for improving care for Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD through CMS’s partnerships with groups of health care providers and suppliers, referred to as ESRD Seamless Care Organizations.

Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE)18

Some demonstration programs that have proven their value have gone on to become permanent programs. PACE is such a program. The PACE model is centered on the belief that it is better for the well-being of seniors with chronic care needs and their families to be served in the community whenever possible.

PACE serves individuals who are aged 55 years or older and who are certified by their state to need nursing home care, are able to live safely in the community at the time of enrollment, and live in a PACE service area. Although all PACE participants must be certified to need nursing home care to enroll in the program, only about 7% of PACE participants nationally reside in a nursing home. If a PACE enrollee does need nursing home care, the PACE program pays for it and continues to coordinate the enrollee’s care.19

PACE programs have had a beneficial impact on a long list of important outcomes, including greater use of adult day health care, fewer skilled home health visits, fewer hospitalizations, fewer nursing home admissions, greater contact with primary care providers, longer survival rates, an increased number of days in the community, better overall health, better quality of life, greater satisfaction with overall care arrangements, and better functional status.20