24 Mammary Ductoscopy

Introduction

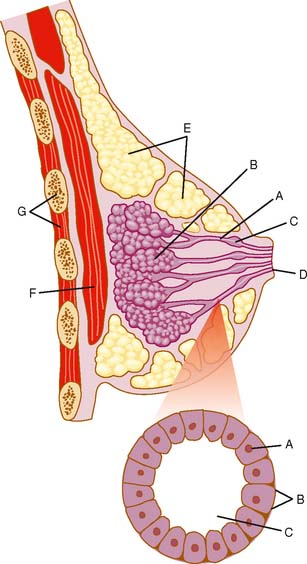

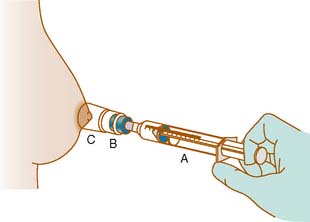

Anatomically the breast comprises ducts and lobules, surrounded by supporting adipose and connective tissue (Fig. 24-1). The epithelial cells that line the ducts and lobules are at risk for malignant degeneration and are the origin of 99% of breast cancers.1 There are three approaches to intraductal breast evaluation: nipple aspiration, ductal lavage (DL), and mammary or fiberoptic ductoscopy (MD). Although nipple aspiration has many strengths, a weakness is the relatively low number of epithelial cells in the specimens. Ductal lavage, which cannulates one or more of the ducts through the nipple orifice, provides a sample with more cells than nipple aspirate fluid (NAF), but the location within the duct from which the cells were collected is unknown. MD allows one to visualize the breast ductal wall, sample the abnormal area for diagnostic purposes, and provides specimens which are generally cellular. Both ductal lavage and MD are usually preceded by nipple aspiration (Fig. 24-2), which identifies ducts containing breast fluid that can be cannulated. NAF distends the duct, making both procedures technically easier to perform. In addition, it has been demonstrated that breasts that provide NAF are at greater breast cancer risk than breasts that do not, implying that NAF-producing ducts are more likely to contain disease.2

MD has been performed for over 10 years.3,4 Direct visualization of the ductal lumen using MD provides a targeted approach to the diagnosis of disease arising in the ductal system, since the lesion can be visualized and samples can be taken through irrigation (lavage) with or without abrasion of the lesion to increase the cellularity of the specimen. Initial studies of MD evaluated women with spontaneous pathologic (unilateral single duct) nipple discharge (PND). MD currently offers a safe and perhaps better alternative to galactography in guiding breast surgery in the treatment of nipple discharge since MD can visualize lesions that do not obstruct the duct, can visualize multiple lesions, and can ensure that all the lesions have been removed.3,5,6 This is especially important, for some women present with multiple intraductal lesions, one of which is benign and the other malignant. Since many of the malignant lesions form in the terminal duct-lobular unit, the malignant lesions tend to be farther from the nipple.7 Some reports suggest that in breasts lacking PND, MD may be useful both in cancer assessment8–12 and, when a preoperative cancer diagnosis has been secured, in determining the optimal margins of surgical resection.8,13

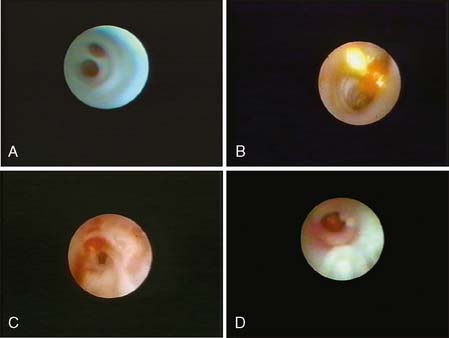

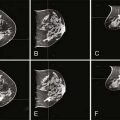

MD can be performed with topical or local infiltration anesthesia. A normal duct internal surface appears lustrous and smooth. Cancer in the duct wall appears white and elevated. Intraductal papillomas form solid nodules and are often yellow unless hemorrhage is present, when they are red (Fig. 24-3).

Technical Aspects of Performing MD

In women with PND, soilage on the bra or beading of fluid on the nipple from a single duct that brings a woman to seek medical attention generally reflects increased breast fluid production due to a disease process within the breast. The increased intraductal fluid distends the duct, allowing the scope to travel deeper into the breast compared with breasts without PND.10

Successful Cannulation and Maneuvering of the Scope within the Ducts

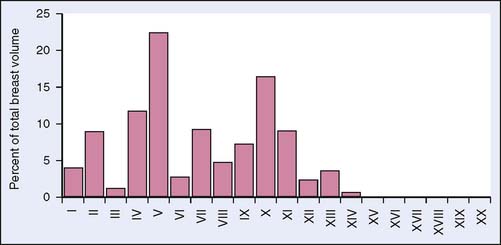

There is a learning curve for the performance of ductoscopic cannulation without perforation11 (Fig. 24-4). Nonetheless, with practice cannulation of one or more nipple ducts can be successfully performed in the overwhelming majority of breasts that have not undergone prior surgery involving the nipple, areola, or central duct system. A recent report that evaluated breast duct anatomy in three dimensions found that seven ducts maintained a wide diameter to the nipple surface and drained approximately 75% of the breast; the remaining ducts (approximately 20) were too small to allow ductoscopic cannulation14 (Fig. 24-5). For MD to maneuver within a duct that has been successfully cannulated, the duct must be of sufficient diameter to accept the endoscope. Thus, MD can in theory evaluate a large portion, but not all of the ductal anatomy of the breast.

The depth to which one can introduce the scope is related to (1) the diameter of the duct versus the diameter of the scope, (2) whether prior breast surgery has been performed, and (3) the pathology within the breast.11 Specifically, the ability of the ductoscope to be introduced more than 10 cm—the length of the MD—before meeting a narrowing or obstruction that blocks further travel is related to the intraductal lesion pathology. One report found that the scope traveled more than 10 cm in 60% of breasts containing an atypical papilloma, in 36% with a papilloma without atypia, in 13% with hyperplastic lesions, and in 5% with invasive breast cancer (IBC).11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree