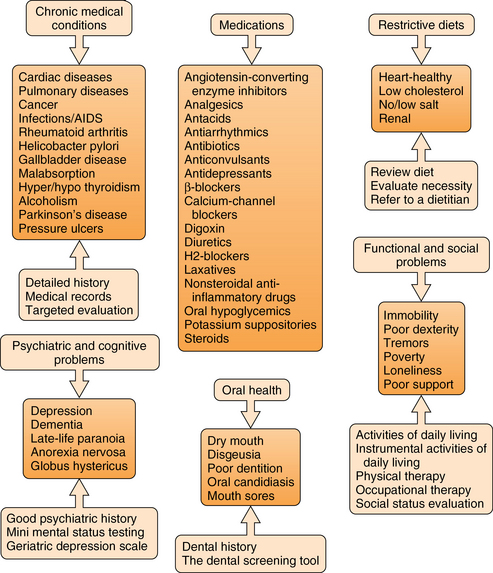

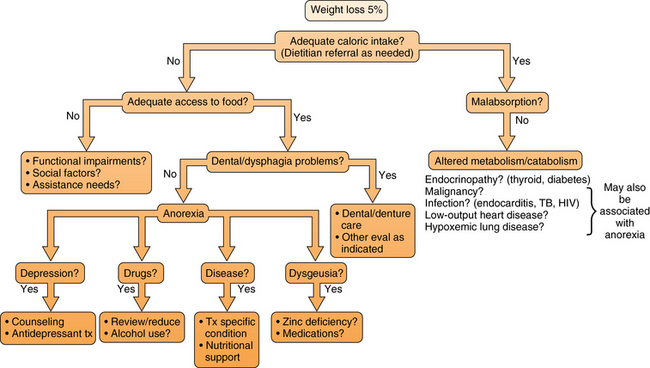

28 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the impact and prevalence of malnutrition and feeding problems in older adults. • List the risk factors for poor nutritional status in older adults. • Describe the pathophysiology of malnutrition and feeding problems in older adults. • List the differential diagnosis for malnutrition and feeding problems in older adults. • Identify assessment tools and management options to address malnutrition and feeding problems in older adults. Malnutrition, more specifically undernutrition, appears to occur frequently in older adults, and has been associated with adverse health outcomes. The outcome of chronically poor nutritional status and unrecognized or untreated malnutrition is frequently considerable dysfunction and disability,1 reduced quality of life, premature or increased morbidity and mortality,2–5 and increased health care costs.4–6 When defined as a decrease in nutrient reserve, malnutrition is prevalent in 1% to 15% of ambulatory outpatients, in 25% to 60% of institutionalized patients, and in 35% to 65% of hospitalized patients.7 Review of the current available incidence data suggests that unintended weight loss is a more frequent problem, especially in the older outpatient population, than previously thought. Malnutrition has been associated with increased mortality in numerous studies, with weight loss often remaining independently associated with mortality after adjustment for baseline health status, which suggests a potential causal role.8–11 Health outcomes other than mortality have also been associated with malnutrition in older adults. Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicated that older women (baseline age 60 to 74, mean 66 years) who lost 5% or more of their body weight over a 10-year follow-up interval had a twofold increase in risk of disability compared to weight-stable women. This risk persisted after adjustment for age, education, smoking, and multiple health conditions.12 Sarcopenia has also been associated with malnutrition and diminished physical function, both of which are associated with geriatric functional decline and mortality. Sarcopenia is a syndrome defined as age-related muscle loss that contributes to functional decline and disability.13 Many older adults undergo changes in their lives (e.g., physiologic, social, family, environmental, economic) that could affect their nutritional intake. Identifying risk factors for malnutrition helps direct further questioning. These risk factors, listed in Figure 28-1, are often multiple and synergistic; if left unchecked these risk factors could weaken nutrition status, increase medical complications, and result in loss of independence.14 Figure 28-1 Risk factors for undernutrition illustrated by clinical approach. (Redrawn from Omran ML, Salem P. Diagnosing undernutrition. Clin Geriatr Med 2002;18:719-36.) As one passes through the life span, changes often occur in body mass and percentage of body fat. Lean body mass declines at a rate of 0.3 kg per year beginning in the third decade. However, this decrease in lean body mass tends to be offset by an increase in body fat, which continues until at least age 65 to 70.15,16 Body weight usually peaks at approximately the fifth to sixth decade of life and remains stable until 65 to 70, after which we see a slow decrease in body weight that continues for the remainder of life.17 Food intake is a motivated behavior between internal signals and environmental cues, and this occurs primarily through the senses of olfaction, taste, vision, and hearing. With aging we often see alterations in these hedonic qualities of food, specifically taste and smell.15,17 The sense of smell declines dramatically with aging, with an increase in odor threshold and a decline in odor identification. Although changes in the sense of taste seem to be less important than changes in the sense of smell, many changes in taste do occur with aging. Among these changes are an increase in taste threshold, difficulty in recognizing taste mixtures, and an increased perception of irritating tastes. These chemosensory changes with aging lead to reduced appetite and subsequent weight loss.18 The regulation of appetite is a complex process involving feedback from a number of peripheral signals and the interactions of a variety of neurotransmitters within the central nervous system. Much of the anorexia of aging seems to be related to the changes in gastrointestinal activities that occur with aging,18–20 with less antral distension, and thus earlier satiety.18,21,22 The physiologic anorexia of aging and its associated weight loss predisposes older persons to develop protein energy malnutrition (PEM). The prevalence rate for PEM is high and has been reported in 15% of community-dwelling older persons, 5% to 12% of homebound patients, 20% to 65% of hospitalized persons, and 5% to 85% of institutionalized older persons.15 PEM has been defined as the presence of both clinical (physical signs such as wasting, low body mass index) and biochemical (albumin, cholesterol, or other protein changes) consistent with undernutrition.23 It is a syndrome characterized by a person’s having too little lean body mass, secondary to decreased energy or protein being supplied. Nutrition screening is the first step in identifying patients who are at risk for nutrition problems or who have undetected malnutrition. It allows for prevention of nutrition-related problems when risks are identified and early intervention when problems are confirmed.24 Early detection and treatment are not only cost-effective but result in improved health and quality of life of the older patient.24,25 An approach to the evaluation of weight loss in the elderly is illustrated in Figure 28-2. Figure 28-2 Weight loss algorithm. (Redrawn from Wallace JI, Schwartz RS. Involuntary weight loss in elderly outpatients—recognition, etiologies, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med 1997;13:717-33.) Several screening and assessment tools specific to the older population are available. Regardless of the tool used, the screening process can be completed in any setting. Screening includes the collection of relevant information to determine risk factors and evaluates the need for a comprehensive nutrition assessment.25 Nutrition assessments are more comprehensive than nutrition screens and are generally completed by a registered dietitian. The mnemonic ABCD stands for anthropometric, biochemical, clinical, and dietary, the four primary components of a nutrition assessment.26 Box 28-1 summarizes the most common data collected during a nutrition assessment of an older patient. Assessments vary in their detail and depth depending on the level of risk identified during the screening process, and the amount of information available at the time of the evaluation. Once the nutrition assessment is complete, it is combined with data from other disciplines to be interpreted and evaluated for the purpose of developing a patient care plan to address identified risks and problems.25

Malnutrition and feeding problems

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Normal aging changes

Anorexia of aging

Protein energy malnutrition

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Nutrition screening and assessment

Malnutrition and feeding problems