BACKGROUND

Large population-based investigations1–4 have shown that Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes preceding pregnancy is associated with a two-to five-fold increased risk of major congenital malformations. This disappointing reality is in sharp contrast to the aspiration expressed in the 1989 St Vincent declaration,5 which proposed as a 5-year target that the outcome of pregnancy complicated by diabetes should approximate that of the non-diabetic population. Optimal glycemic control before and during pregnancy in women with diabetes is critical to obtain a satisfactory maternal and neonatal outcome. As organogenesis is complete by 8 weeks, inadequate preconceptional glycemic control is associated with an increased risk of congenital abnormality.6,7 Diabetes in pregnancy is also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, which is also presumed to be secondary to poor glycemic control.6,7 As expected, gestational diabetes developing in late pregnancy has not been associated with an increased risk of either congenital malformations or miscarriage.4

TYPES OF CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS

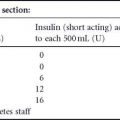

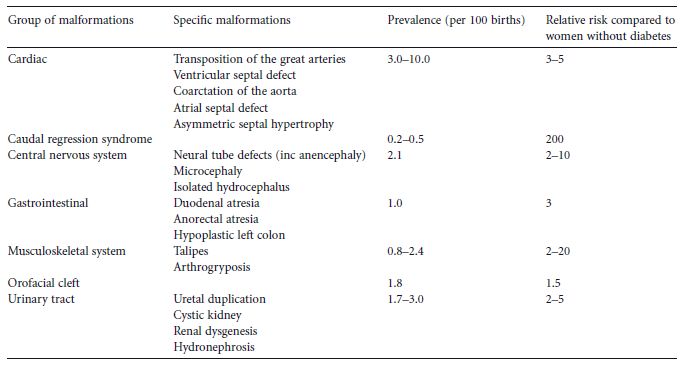

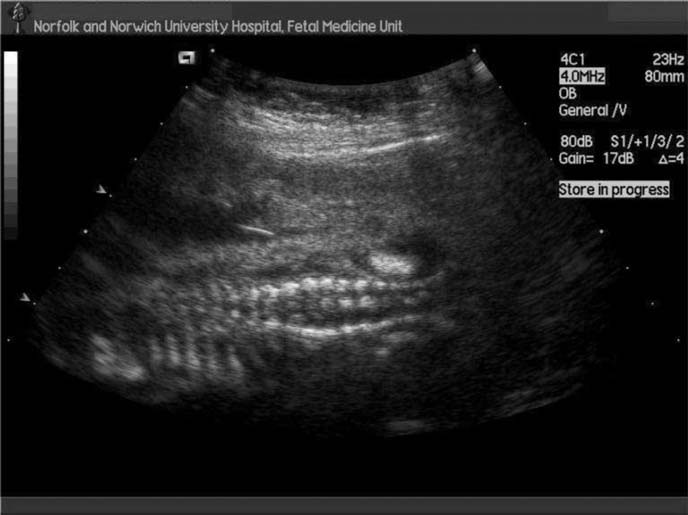

Organogenesis takes place between 2 and 8 weeks of gestation and the malformations which are found with increased frequency in association with maternal diabetes must have their origins in some type of insult occurring during this period.8 Glycemic control in this time period is therefore of the utmost importance with regard to the possibility for the development of malformations.7 All types of major malformations are more frequent in offspring of diabetic mothers (Table 14.1). Cardiac malformations, e.g. transposition of the great vessels, ventricular or atrial septum defects, and coarctation of the aorta are the most common.1,4 However, malformations in the central nervous system (e.g. neural tube defects; Fig. 14.1) are also relatively common, as are renal and skeletal malformations, and duodenal and anal atresia. In addition, one type of malformation – caudal regression syndrome – is exceedingly rare outside of diabetes in pregnancy. Many infants demonstrate multiple major malformations. In one study of pregnant women who had Type 2 diabetes, the higher the initial maternal fasting glucose the more likely multiple, rather than single, fetal anomalies.9 The increased frequency of major malformations is probably the reason for the increased risk of miscarriage in women with diabetes.

Table 14.1 Detectable major congenital malformations in babies of women with pregestational diabetes. (Adapted from National Collaborating Centre for Women’ s and Children’ s Health4.)

ROLE OF METABOLIC CONTROL IN MALFORMATIONS AND MISCARRIAGES

A recent systematic review7 of 13 mainly observational studies found an overall three-fold increased risk of malformations in women with diabetes compared to the background population. The risk of major malformations was found to be increased five-fold and the risk of miscarriages three-fold when there was poor metabolic control. For each 1% reduction in HbA1c the risk of severe malformations was reduced by around 50%. Relating the percentage reduction in HbA1c to relative risk of adverse pregnancy events may be useful in motivating women to achieve optimal control prior to conception. Those diabetic women offered prepregnancy care and achieving HbA1c concentrations less than 7% before conception, have a considerably reduced risk of adverse outcomes, including malformations, compared to those pregnant women with diabetes who do not.10. This is supported by results from a new large population-based Danish study,11 which showed no clear threshold of HbA1c for the risk of congenital malformations, although the risk was not statistically increased when periconceptual HbA1c was below 7%, which corresponded to fewer that 3 SDs above the mean for the background population. Intensified glycemic control with average premeal capillary glucose values less than 6 mmol/L (< 108 mg/dL) and 1-hour postprandial values less than 7.5mmol/L (<135mg/dL), commenced before and continuing during early pregnancy, was found to reduce malformation rates to a level approaching the background risk.12

Fig. 14.1 Ultrasound scan showing neural tube defect with splaying of vertebra.

The precise mechanism responsible for fetal teratogenesis in pregnancy complicated by diabetes is unclear. Freinkel13 introduced the concept of “pregnancy as a tissue culture experience,” proposing that the fetus develops in an “incubation medium” that is totally derived from maternal fuels. Experimental animal studies have suggested that the major teratogen in pregnancy is hyperglycemia, although other diabetes-related factors may adversely influence fetal outcome. Increased levels of ketone bodies or episodes of severe hypoglycemia may also be teratogenic.12 Se veral possible teratologic pathways in embryogenic tissues have emerged, including alterations in the metabolism of inositol, arachidonic acid, and reactive oxygen species.

The embryonic formation of sorbitol, glycated proteins, the level of folic acid, and the maternal and fetal genotypes are also suggested to influence the complex teratologic events in diabetes in pregnancy. The subject has been extensively studied and reviewed by Eriksson et al.14

INFLUENCE OF OBESITY AND METABOLIC SYNDROME

Obesity per se is associated with menstrual irregularities, infertility, miscarriages, and other adverse pregnancy outcomes, and in many cases is part of the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).15 A population-based study found that offspring with spina bifida, heart defects, anorectal atresia, hypospadias, limb reduction defects, diaphragmatic hernia, and omphalocele were significantly more likely to have had obese mothers than controls, with odds ratios ranging between 1.33 and 2.10.16 The mechanisms underlying these associations are not yet understood, and whether they are related to undiagnosed diabetes or other metabolic changes associated with obesity16 remains unanswered.

The possibility that the combination of maternal obesity and prepregnancy diabetes mellitus potentiates the risk for neural tube defects has been investigated.17 The presence of one feature of the metabolic syndrome was associated with a two-fold increased risk for a neural tube defect and two or more features with a six-fold higher risk, although no allowance was made for glycemic control. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome might therefore add to the risk of congenital malformations seen with diabetes. This may explain the observation that women with Type 2 diabetes have similar rates of congenital malformations to those with Type 1 diabetes, despite HbA1c values in women who have Type 2 diabetes tending to be lower in the first trimester.18

ROLE OF FOLIC ACID

It is well established that the folate requirements increase during pregnancy and that supplementing 0.4 mg of folic acid/day to the general population reduces the risk of neural tube defects.19 In addition, it has been reported that folic acid supplementation may prevent other birth defects, such as heart defects, cleft lip and palate, limb deficiency defects, and urinary tract abnormalities.20 In animal models, folic acid supplementation reduces glucose-induced congenital malformations with a threshold effect.21 Furthermore, mRNA expression of folic acid-binding protein, a folic acid transporter, is decreased in the diabetic state.21

In humans, the protection afforded by folic acid supplementation against diabetes-associated malformations is less clear. Multivitamin supplements have been reported to reduce the risk of congenital malformations,22 but the compositions of the supplements were unknown and the benefit probably included that of overall prepregnancy care. In recent years several national bodies4,23,24 have recommended high doses of folic acid (4–5 mg/day) to diabetic women before and during early pregnancy. However, the wisdom of this strategy has been questioned25 since a high folate intake might be associated with promotion of neoplasia. Therefore, many centers around the world still advocate the use of 0.4 mg of folic acid/day supplementation. In a small series using the latter strategy, low rates of congenital malformations were reported.26

A consensus exists that all women with diabetes preparing for pregnancy are advised to take supplementary folic acid. Whether the dose should be 0.4, 1 or 5 mg/day remains unclear. Supplementation should be continued for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

ROLE OF ORAL AGENTS

Biguanides and sulfonylureas

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree