Chapter 11

Major trauma

Introduction

Beyond the age of 70 years, mortality after a traumatic injury significantly increases in comparison to that in younger patients (1). Older persons account for 28% of deaths due to trauma while representing only 12% of the overall trauma population (2).

Mechanisms of injury differ in the older patients with 60% of trauma due to falls, and 25% from motor vehicle accidents. Falls occur due to a multitude of factors such as gait instability, leg weakness, postural hypotension, and acute illness (Chapter 8). Slower reaction times, cognitive decline, reduced visual acuity, hearing impairment, physical disabilities, and slower ambulation are contributing factors to motor vehicle accidents in older drivers and pedestrians. The presence of comorbidities and polypharmacy in older adults has been shown to increase the risk of motor vehicle collision (3). Loss of control at the wheel may be triggered by an acute cardiac or cerebrovascular event.

Definition

Major trauma describes serious and often multiple injuries resulting from an external source or impact and where there is a strong possibility of death or disability (4).

Background

A lower transmitted kinetic injury results in more severe injuries due to reduced bone density and other degenerative changes. Around one quarter of older patients in motor vehicle accidents sustain chest trauma such as rib fractures. Fractures of the cervical spine, hip and pelvic ring are common. There is a higher incidence of fatal injuries such as intracranial haemorrhage.

The high mortality rate reflects comorbidities, decreased physiological reserve and medications such as anticoagulants or antihypertensives rather than chronological age alone. For example, trauma patients with heart failure have more than double the risk of death; if they are also taking β-blockers or warfarin this risk is even higher (5). Despite the increased mortality rate, geriatric trauma is frequently under-triaged to local hospitals rather than major trauma centres, potentially delaying access to expert care and definitive treatment (6). Reasons for this may include delayed recognition of shock; an under-appreciation amongst emergency medial services of the increased susceptibility of the older population to minor injury mechanisms; and reduced representation of the older patient in trauma triage guidelines.

A large proportion of older trauma patients return to independent living (7), and an initial aggressive approach to resuscitation should be pursued. In an older patient with catastrophic injuries, a decision in consultation with family and the trauma team to switch to palliative treatment may sometimes be appropriate.

Initial Approach

Management of an older person with a traumatic injury should begin with a primary survey to identify and treat any life-threatening issues, according to Advanced Trauma Life Support® (ATLS®) Guidelines (8). Vital signs can be falsely reassuring and increased mortality has been shown in older patients with heart rates greater than 90 beats/min and a systolic blood pressure less than 110 mmHg (9). Older patients report less pain for the same injury than do younger trauma patients, also potentially falsely reassuring clinicians that an injury is less severe (10). Figure 11.1 illustrates particular considerations when evaluating the older trauma patient.

Disability

Cervical spine

Breathing

|  Figure 11.1 Considerations in the primary survey in an older adult. | Circulation

Exposure

|

Airway and cervical spine immobilisation

| Assess airway patency while immobilising the cervical spine. Provide high-flow oxygen. Inspect the airway for foreign bodies, loose teeth, dentures or facial injuries. In an obstructed airway perform a jaw-thrust and insert an oropharyngeal airway. Prepare for intubation or a surgical airway if necessary. |

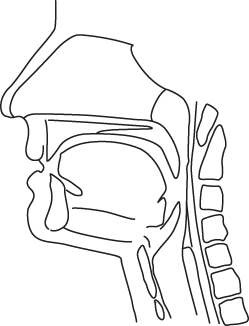

Anatomical changes in the airway of an older adult can make airway maintenance and tracheal intubation more difficult (Figure 11.2).

| Brittle or loose teeth may fracture easily during airway manoeuvres Bag-valve mask ventilation may be difficult in edentulous patients with loss of maxillary subcutaneous tissue. Malfitting or displaced dentures may contribute to this Reduced mouth opening secondary to microstomia or temporomandibular arthritis Airway bleeding may occur during insertion of airway adjuncts or laryngoscopy due to friable nasal and pharyngeal tissue | Airway patency may be lost earlier due to decreased oropharyngeal reflexes Figure 11.2 Factors that may lead to difficult airway management in the geriatric patient. | Increased risk of aspiration as a result of decreased oropharyngeal reflexes and slower gastric emptying Decreased cervical spine and atlanto-occipital joint mobility makes intubation potentially difficult even if the cervical spine has been cleared The atlanto-occipital joint may be unstable due to rheumatoid arthritis or degenerative changes Maintenance of in-line cervical stabilisation is necessary unless the cervical spine has been cleared |

Endotracheal intubation should be considered early in patients with an unprotected airway due to reduced level of consciousness or in significant chest trauma. Rapid sequence induction is associated with increased complications in the older person such as hypotension and hypoxia (11). Reduced doses of induction agents are required to avoid post-induction hypotension.

Breathing

| Expose the neck, chest and axillae and inspect and palpate for visible injuries, tracheal deviation, chest movement, and subcutaneous emphysema. Feel for tenderness along the ribs, clavicle and sternum. Percuss the chest to elicit any dullness or hyper-resonance. Listen for bilateral air entry. |

The older patient has a reduced or delayed response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Arterial blood gases are useful to assess adequacy of oxygenation and ventilation. Asking the patient to take a deep breath in and cough can provide a good indication of respiratory function.

Chest injuries including rib fractures, pneumothoraces and pulmonary contusions are poorly tolerated and associated with a much higher rate of complications, including atelectasis and pneumonia.

Circulation with haemorrhage control

| Identify any external haemorrhage, and apply direct pressure. Simple scalp lacerations or facial injuries may bleed profusely |

| Assess pulse rate, volume and regularity. Measure blood pressure. Assess skin colour and capillary refill. Attach cardiac monitoring and obtain an ECG |

| Examine the abdomen, pelvis and thighs for signs of internal bleeding due to blunt injury or fractures. Consider application of a pelvic binder or splint |

| Perform a FAST (focused assessment with sonography for trauma) or eFAST ultrasound scan at the bedside to identify free fluid in the abdomen, pericardial fluid or pneumothorax |

| Insert two large-bore IV lines and take a blood sample including for cross-match. Give IV fluid or blood products depending on findings and likely injuries |

Medications such as β-blockers or antihypertensives, or the presence of a pacemaker, may reduce the patient’s compensatory response to haemorrhage and mask hypovolaemic shock. Pre-existing conditions, such as cardiac failure, may confuse the clinical picture. Serial base deficit and blood lactate measurements may identify impaired perfusion due to occult haemorrhage. Anti-coagulation may need to be urgently reversed (Box 14.5).

Abdominal injuries occur at a similar rate to that in younger patients, but splenic injuries are less common due to involution of the spleen with ageing (12). Abdominal examination is less reliable in older patients (Chapter 15), and a low threshold for CT should be adopted.

Significant pelvic fractures in patients aged over 60 have a high likelihood of retroperitoneal bleeding (13). Lateral compression fractures are five times more common than anterior compression fractures in the older adult (14), and these are more likely to cause significant haemorrhage with a greater need for angiography, despite the same being considered a more benign fracture in younger patients (15). Mortality in patients suffering pelvic fracture has been reported to be between 12% and 21% (12). Occult bleeding into the pelvis may be detected by performing serial full blood count, lactate and base deficit. Repeat imaging or angiography may be necessary (16).

Disability

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree