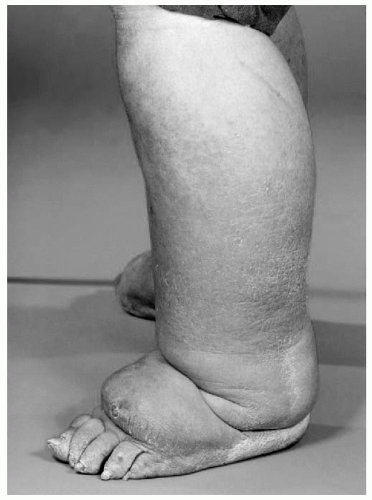

Lymphedema is defined as the accumulation of a relatively protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space of tissues due to a low-output failure of the lymphatic system, that is, lymph transport is reduced (

1).

Lymphedema is usually classified into “primary,” which defines a group of lymphedemas arising from a congenital lymphatic dysplasia, and “secondary,” in which extrinsic factors damage the lymphatics. Lymphedema associated with cancer and its treatment is therefore “secondary lymphedema.”

However, the formation of edema in patients with advanced cancer is usually more complex than this. It is helpful, therefore, to consider the mechanisms of edema formation. Edema is the accumulation of excessive fluid in the interstitial space and results from an imbalance between the formation and drainage of interstitial fluid.

The Formation of Edema

Fluid enters the interstitial space by capillary filtration. The amount of filtrate is determined by the “Starling” forces acting across the capillary wall. These are the hydrostatic pressure gradient, which tends to push fluid from the capillary into the interstitial space, and the colloid osmotic pressure gradient due to plasma proteins that are retained in the capillary which tends to draw water from the interstitial space into the capillary. The volume of filtrate will also be determined by the permeability of the capillary wall.

In the past, it was felt that this process occurred largely in the arterial end of the capillary and a degree of reabsorption occurred at the venous end of the capillary. However, current thinking suggests that once fluid reaches the interstitial space its route of exit is through the freely permeable initial lymphatic capillary, that is, lymphatic drainage (

2). Therefore, edema occurs whenever capillary filtration exceeds lymphatic drainage.

Table 27.1 shows the changes in capillary filtration and lymphatic drainage in a variety of chronic edemas.

In venous edema, for example, in chronic venous insufficiency of the leg, capillary filtration is raised because of increased hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries, but this results in increased lymphatic drainage due to the spare capacity of the lymphatic system to transport fluid. When this capacity is exceeded, then edema occurs (high-output failure of the lymphatics). If high-output failure of the lymphatic system persists, then there is a gradual deterioration in lymphatic transport capacity and worsening edema develops. This situation is often called edema of mixed etiology, that is, mixed venous and lymphatic.

In patients with reduced mobility, particularly those who spend a lot of time sitting in a chair, so-called dependency edema can occur. This is, again, a mixture of lymphatic and venous edema. Poor mobility means that the usual muscle pump that aids both venous and lymphatic drainage is impaired, and therefore, capillary filtration is increased and lymphatic drainage is reduced.

In patients with hypoalbuminemia, the colloid osmotic pressure in the plasma is reduced, and therefore, capillary filtration is increased, and edema can occur if lymphatic drainage is unable to cope with this.

Post-cancer Treatment Edema

It has long been assumed that axillary lymphadenectomy carried out as part of the surgical treatment for breast cancer has led to lymphedema of the arm in some women because of simple damage to the lymphatics. The addition of radiotherapy to the axilla may increase the damage to the lymphatics. However, in recent years, it has become clear that this is perhaps too simplistic a view of the etiology of the edema. Studies have shown that, contrary to predictions, lymph flow is increased in both the “at-risk” and contralateral arm in women who go on to develop lymphedema compared with

those who do not. (

3). This suggests that there is a constitutional tendency to lymphedema in some women possibly as a result of raised capillary filtration and lymphatic drainage (high-output failure) (

4).

Similar mechanisms may contribute to the formation of edema in people who have had groin lymph node dissections for the treatment of tumors such as melanomas of the leg.

Edema in Advanced Cancer

In patients with advanced cancer, the edema is usually of complex etiology (

Table 27.2). A patient may have lymphatic obstruction due to metastatic disease in the lymph nodes or due to previous treatment. There may be extrinsic venous compression causing venous hypertension or even venous thrombosis. In advanced disease, hypoalbuminemia is common, and finally, in association with the cachexia of advanced disease, weakness and immobility may result. These factors will lead to increased capillary filtration and reduced lymphatic drainage. This situation is often seen in patients with advanced pelvic malignancies.