Lymphedema

Vaughan Keeley

For patients with cancer, lymphedema can occur as an aftermath of treatment or it can be a feature of advanced disease. Lymphedema of the arm is a fairly common sequel to treatment for breast cancer, and leg edema may be present in patients with advanced pelvic cancers.

The approaches to management of these two groups may be different. In the former, “supportive” treatment would aim to minimize the edema and enable the patient, with successfully treated cancer, to live as normally as possible with the problem. In the latter, a “palliative” approach would aim to alleviate symptoms as much as possible while ensuring that any burden of treatment would be outweighed by the benefits. Edema in patients with advanced cancer may be only one of a number of problems that is experienced, and would therefore need to be considered in this context.

Pathophysiology

Lymphedema is defined as the accumulation of a relatively protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space of tissues due to a low output failure of the lymphatic system, that is, lymph transport is reduced (1).

Lymphedema is usually classified into “primary”, which defines a group of lymphedemas arising from a congenital abnormality of the development of the lymphatic system, and “secondary”, in which extrinsic factors cause damage to the lymphatics. Lymphedema associated with cancer and its treatment is therefore secondary lymphedema.

However, the formation of edema in patients with advanced cancer is usually more complex than this. It is helpful, therefore, to consider the mechanisms of edema formation. Edema is the accumulation of excessive fluid in the interstitial space and results from an imbalance between the formation and drainage of interstitial fluid.

The Formation of Interstitial FluidA

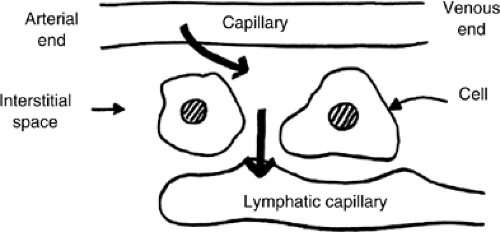

Fluid enters the interstitial space by capillary filtration. The amount of filtrate is determined by the “Starling” forces acting across the capillary wall. These are the hydrostatic pressure gradient, which tends to push fluid from the capillary into the interstitial space, and the colloid osmotic pressure gradient due to plasma proteins that are retained in the capillary which tends to draw water from the interstitial space into the capillary. The volume of filtrate will also be determined by the permeability of the capillary wall (Fig. 23.1)).

In the past it was felt that this process occurred largely in the arterial end of the capillary and a degree of reabsorption occurred at the venous end of the capillary. However, current thinking suggests that once fluid reaches the interstitial space its route of exit is through the lymphatic capillary, that is, lymphatic drainage (2). Therefore, edema occurs whenever capillary filtration exceeds lymphatic drainage.

Table 23.1 shows the changes in capillary filtration and lymphatic drainage in a variety of chronic edemas.

In venous edema, for example in chronic venous insufficiency of the leg, capillary filtration is raised because of increased hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries, but this results in increased lymphatic drainage due to the spare capacity of the lymphatic system to transport fluid. When this capacity is exceeded, then edema occurs (high output failure of the lymphatics). The edema in this situation is believed to be of lower protein content than in true lymphoedema described in the preceding text (1). If high output failure of the lymphatic system persists, then there is a gradual deterioration in lymphatic transport capacity and an element of true lymphedema occurs. This situation is often called edema of mixed etiology, that is, mixed venous and lymphatic.

In patients with reduced mobility, for example, those with chronic conditions, which means that they spend a lot of time sitting in a chair, the so-called dependency edema can occur. This is, again, a mixture of lymphatic and venous edema. Poor mobility means that the usual muscle pump that aids both venous and lymphatic drainage is impaired, and therefore capillary filtration is increased and lymphatic drainage reduced.

In patients with hypoalbuminemia the colloid osmotic pressure in the plasma is reduced, and therefore capillary filtration is increased, and edema can occur if lymphatic drainage is unable to cope with this.

Table 23.1 Chronic Edemas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Post-cancer Treatment Edema

It has long been assumed that axillary lymphadenectomy carried out as part of the surgical treatment for breast cancer has led to lymphedema of the arm in some women because of simple damage to the lymphatics. In addition, those women who have had radiotherapy to the axilla have also been believed to develop lymphedema because of damage to the lymphatics caused by the radiotherapy treatment. However, in recent years, it has become clear that this is perhaps too simplistic a view of the etiology of the edema. Studies have shown that in many women there are also changes in venous (3) and arterial (4) flow in the affected arm. In some women there may also be an underlying predisposition to developing lymphedema (5). Finally, the distribution of the edema, for example, sometimes sparing the hand, sometimes affecting only the hand, and so on, does not necessarily fit with a simple model (6).

Similar mechanisms may contribute to the formation of edema in people who have had groin lymph node dissections for the treatment of tumors such as melanomas of the leg.

Edema in Advanced Cancer

In patients with advanced cancer, the edema is usually of complex etiology (Tables 23.1 and 23.2). A patient may have lymphatic obstruction due to metastatic disease in the lymph nodes or due to previous treatment. There may be extrinsic venous compression causing venous hypertension or even venous thrombosis. In advanced disease, hypoalbuminemia is common, and finally, in association with the cachexia of advanced disease, weakness and immobility may result. These factors will lead to increased capillary filtration and reduced lymphatic drainage. This situation is often seen in patients with advanced pelvic malignancies (Table 23.2).

Chronic Edema

It is likely that very few edemas seen in patients treated for cancer are pure lymphedemas. Indeed, it may be better to use the term “chronic edema.” This is defined as:

“A broad term used to describe edema which has been present for more than 3 months and involves 1 or more of the following areas: limb/s, hands/feet, upper body (breast, chest, shoulder, back), lower body (buttocks, abdomen), genital (scrotum, penis, vulva), head, neck, or face. Edema which develops because of a failure in the lymphatic system is referred to as lymphedema, but chronic edema may have a more complex underlying etiology” (7).

Nevertheless the term lymphedema tends to be used clinically and in current publications.

Incidence

The literature is not clear about the precise incidence of lymphedema following treatment for cancer (8). Difficulties arise because of a lack of agreement about the definition of the degree of swelling that constitutes lymphedema, and the different ways in which measurements are made.

Cancer treatment–related lymphedema is most commonly seen in patients who have been treated for breast cancer, gynecologic cancers, urologic cancers, those who have had groin dissections for treatment for malignant melanoma, and those who have been treated for head and neck cancer.

Table 23.2 Causes Of Edema in Advanced Cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Breast Cancer–related Lymphedema

Breast cancer–related lymphedema is the type that has been studied most, but even in this group there remain a number of uncertainties about the true incidence and etiology (8). The prevalence of edema in women who have received conventional treatment for breast cancer is reported to be around 25–28% (9), although in some reports the figure is as low as 6% (10). This “conventional” treatment usually involves axillary node sampling in which it is intended to remove a sample of four nodes for staging purposes. Removal of the tumor itself is usually by mastectomy or wide local excision together with postoperative radiotherapy in some instances. It has been argued that with the use of sentinel node biopsy, the incidence of lymphedema may be reduced to approximately 3% (11).

Some of the variations in the results reported may relate to different lengths of follow-up as well as measurement techniques. There is a well-recognized pattern of delay in the onset of swelling which may occur several years after the primary treatment, even in the absence of recurrence of cancer.

The literature is also not consistent in terms of the risk factors identified for the development of lymphedema following treatment of breast cancer, but some of the common factors that emerge include (8) the following:

Radiotherapy

The extent of axillary node dissection

Combined axillary surgery and radiotherapy

Obesity

Surgical wound infection

Tumor stage

Extent of surgery

Attempts have therefore been made to reduce the incidence of breast cancer–related edema by modifications of surgical and radiotherapy techniques. The following factors should help with this (12):

Wide local excision rather than mastectomy

Sentinel node biopsy rather than axillary node sampling

Avoidance of axillary radiotherapy following axillary node clearance

Modification of radiotherapy techniques

Avoidance of arm infections and inflammation

Because of the often-delayed appearance of lymphedema following treatment, it will take some time to determine whether any of these changes will bring about the desired reduction in incidence.

Gynecologic Cancer

The prevalence of lower limb lymphedema after treatment for gynecologic cancers depends upon the type of cancer and surgery carried out. Nevertheless, one study has shown an overall prevalence of 18% in women treated for all gynecologic cancers (13). In 16% of these women the edema developed between 1–5 years following treatment. The prevalence was 47% in women treated for vulval cancer with lymphadenectomy and radiotherapy. However, other studies of vulval cancer have shown a range of between 9% (14) and 70% (15).

Urologic Cancers

There is very little evidence in the literature concerning the incidence of lymphedema of the legs and genitalia following treatment for urologic cancers. The incidence does seem to vary according to the type and location of a tumor and may be up to 50% in advanced stages of penile cancer or following its treatment (16).

Groin Dissection

Again, the literature shows a varied incidence. In one study of groin dissection for malignant melanoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, the overall incidence of mild to moderate lymphedema was 21% (17). Sentinel node biopsy in the management of melanomas of the leg has been advocated to reduce the incidence of post-treatment lymphedema.

Other studies have shown the incidence of measurable lymphedema after groin dissection to be >80% after 5 years (18).

Head and Neck Cancer

Lymphedema of the face and submental region can occur following treatment for head and neck cancer. This treatment may involve bilateral lymph node dissections of the neck and postoperative radiotherapy, but there is little evidence in the literature to show how common the problem is.

Incidence of Edema in Advanced Cancer

Edema is a common problem in advanced cancer although, as described in the preceding text, its etiology can be complex. In one study it was shown that edema occurred in approximately one third of patients with advanced disease and was associated with a poor prognosis (19).

Clinical Features

Lymphedema Due to Cancer Treatments

Symptoms and Signs

Lymphedema is often described as a firm nonpitting edema. However, in the early stages of its development, the swelling may be soft and pit easily on pressure. As the condition progresses, the edema becomes firmer because of the development of fibrosis and fatty tissue within the subcutaneous space.

The development of typical skin changes in lymphedema also takes a variable amount of time and seems to be more prominent in leg edema than in arm edema.

These changes include the following:

An increase in skin thickness

Hyperkeratosis: a buildup of horny scale on the skin surface

A deepening of skin creases, especially round the ankle and base of toes (Figure 23.2)

A warty appearance to the skin as hyperkeratosis worsens

Lymphangiectasia: small blisters due to dilated lymph vessels. These may burst and cause significant leakage (lymphorrhoea). These are said to occur particularly following radiotherapy, which causes fibrosis and obstruction of the deep collecting lymphatics.

Papillomatosis: with papules consisting of dilated skin lymphatics surrounded by rigid fibrous tissue which may give a “cobblestone” appearance to areas of skin, particularly on the legs

The physical sign, Stemmer’s sign, is the inability to pick up a fold of skin at the base of the second toe and its presence is said to be diagnostic of lymphedema (20).

Pain may be a feature of lymphedema. In one study of various types of lymphedema, 57% of patients reported pain, while 32% described “tightness.” Patients with active cancer were more likely to report both tightness and pain (21). Four types of pain were described: tissue pressure, muscle stretch, neurologic, and inflammation. Neurologic pain tended to occur in patients with advanced cancer. When lymphedema first appears, particularly if the swelling develops quickly, pain may occur which subsequently subsides.

In the early stages of the development of lymphedema, limb function and mobility may be normal, but as swelling develops, particularly around the joints, mobility is reduced and this may in turn exacerbate the swelling due to the reduced action of the muscle pump on lymphatic drainage. As a result, the limb can become increasingly heavy and cause further pain and discomfort at the shoulder or hip in the case of arm and leg edema, respectively.

Lymphedema after Breast Cancer Treatment

Patients may often develop symptoms before any objective evidence of lymphedema (22). These symptoms may include a feeling of fullness, tightness, or heaviness of the arm, shoulder, or chest, and an altered mobility of the shoulder. Associated with arm swelling, there may be truncal edema and an asymmetric increase in the subcutaneous fatty tissues.

Some patients may develop symptoms shortly after the initial treatment, and it may be that these are transient changes that will resolve. However, it is not clear whether these will predispose to subsequent development of more persistent lymphedema (22).

In women who have had treatment for breast cancer and who develop edema of the arm, it is important to consider whether there may be recurrence of the breast cancer or whether the edema has developed because of an acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Psychosocial Aspects

Lymphedema, especially following cancer treatment, can be associated with a significant psychological morbidity (23). These may relate to issues of altered body image, disability, and the fear of cancer recurrence. The development of arm swelling can be particularly distressing for women who have had to cope with surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy for breast cancer, and their consequences. To have undergone all these treatments and then be left with persistent arm edema as a constant reminder of previous breast cancer can be traumatic.

Complications

The most common complications of lymphedema are as follows:

Cellulitis

Lymphorrhoea

DVT

New malignancies, especially lymphangiosarcoma

Cellulitis

In lymphedematous limbs there is an altered local immune response (24). This leads to a predisposition to developing infections and new malignancies in the affected area. The most important infection is cellulitis, which can not only be very unpleasant for the sufferer but may also lead to further damage to the lymphatic system and worsening edema, particularly if the cellulitis is recurrent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree