The treatment of lung cancer is in constant evolution. As the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, this highly lethal malignancy presents numerous therapeutic challenges. This chapter focuses on patients with stage III and IV lung cancer or in other words, locally advanced and metastatic lung cancer. About 80% of patients with lung cancer develop non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) type histology and these are the patients upon which this chapter will focus. The remaining 20% develop small cell carcinoma, which when locally advanced, given current therapeutics, is a uniformly nonsurgical disease treated primarily with chemotherapy. Despite increasing resolution in diagnostic imaging and attempts to screen high-risk patients, 65% of NSCLC patients continue to present with advanced disease (stage III or higher).1 Nevertheless, this is a heterogeneous group of patients who require a spectrum of management strategies ranging from curative intent therapy to palliative care. The common thread within this spectrum is the added value of customized care that implements a multimodality approach. Advances in our understanding of lung cancer biology have led to the incorporation of targeted therapies that likely hold the greatest promise for improving outcomes in this patient population.2 Refinements in stereotactic radiotherapy protocols, aggressive multiagent chemotherapy regimens, advances in surgical technique and recovery have all contributed to improved survival from advanced lung cancer. However, in many clinical scenarios the ideal combination of these modalities and their timing remains to be determined. This chapter summarizes the state of the art in the care of advanced NSCLC with the understanding that several areas remain controversial and that the coming years will bring significant changes leading to improved outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Despite reduced rates of smoking in the general population, lung cancer remains the most common malignancy.1 In the United States, it is the leading cause of cancer death with 228,190 new cases and 159,480 deaths estimated in 2013 representing 27.5% of all cancer-related deaths. Indeed, despite improvements in care, lung cancer portends a very poor prognosis with a mere increase in 5-year survival from 11.4% in 1975 to 17.3% in 2005. The poor survival rates are largely related to the high frequency of lymph node spread and metastatic disease present at the time of diagnosis. Although regionalized disease can still be cured, with 5-year survival rates in the vicinity of 26%, metastatic disease is virtually incurable with 5-year survival rates of 3.9% based on most recent data.1 When seen from this perspective, treatment of advanced lung cancer may seem almost futile; however, several specific clinical scenarios provide the opportunity for cure with current management strategies. Palliation when cure is not realistic remains of utmost importance. Moreover, with such bleak results the opportunities for significant progress and quantum leaps in survival from this aggressive disease are abundant.

As can be deduced from the high proportion of patients who present with advanced disease, lung cancer tends to cause symptoms late in its course. Most patients will be initially asymptomatic; however, with advancing disease it is not uncommon for patients to present with such nonspecific symptoms as dry unproductive cough, weight loss, fatigue, and shortness of breath. Other symptoms that raise concern for advanced disease include hemoptysis, chest wall pain, peripheral or central neurological symptoms, and a range of paraneoplastic syndromes. Patients with lung cancer often present initially with pneumonia or what appears to be pneumonia and this can be a source of delay in definitive diagnosis. Such patients are treated for pneumonia and will frequently undergo a period of observation subsequent to antibiotic treatment and several weeks to months can go by before it becomes clear that the patient is suffering from a postobstructive pneumonia secondary to an invasive lung neoplasm. Clinicians must, therefore, keep a high degree of suspicion, particularly in patients at high risk for developing lung cancer. Indeed, a neoplastic process must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of new chest x-ray findings such as opacities or infiltrates.

Some important syndromes are pathognomonic of advanced lung cancer and should be readily recognized. Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is most frequently caused by bronchogenic lung cancer, though it can also result from mediastinal lymphadenopathy or from a large mediastinal mass such as a thymic neoplasm. SVC syndrome is caused by compression or invasion of the SVC leading to venous obstruction and so the symptoms it causes are commensurate to the degree of congestion. When identified, an aggressive diagnostic workup should ensue in order to initiate treatment promptly. SVC syndrome is characterized by dyspnea, headache, facial and upper limb edema, distended neck veins, and can be accompanied by Pemberton’s sign where these symptoms are exacerbated or brought on upon raising both of the patient’s arms. Rarely, it can cause such severe venous occlusion that cerebral edema and death can occur.3

Pancoast’s syndrome was described in 1924 by the American radiologist Henry Pancoast, who associated the constellation of Horner’s syndrome, shoulder pain radiating from the axilla and scapula down to the ulnar aspect of the ipsilateral arm, atrophy of arm and hand muscles, and SVC syndrome.4 These findings are indicative of a superior sulcus tumor with compression or invasion of the brachial plexus and SVC. Although rarely seen in its full expression today, any element of Pancoast’s syndrome in the context of a superior sulcus mass is highly suspicious for advanced lung cancer. Such apical chest tumors are often referred to as Pancoast or superior sulcus tumors and they present a number of clinical challenges that will be discussed in the section on complex clinical scenarios.

Finally, clinical assessment of any patient suspected of having lung cancer should include an assessment of the vocal cords. Advanced stage lung cancer can easily invade the recurrent laryngeal nerve(s) and it is therefore important to document this early in the diagnostic workup. Although ominous, a paralyzed vocal cord in a patient with lung cancer may not necessarily be due to advanced disease. One must be able to differentiate what is caused by the patient’s disease and what can develop subsequently as a result of diagnostic interventions like mediastinoscopy or treatment, where the nerves may be injured as part of a mediastinal lymph node dissection.

Lung cancer staging is based on the TNM system, regulated by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), and is currently in its 7th edition.5 The highlights pertain to the tumor size, invasion of adjacent organs, degree of lymph nodal spread and metastasis to distant organs. Some important features worthy of note pertain to the T stage, which in the T1 and T2 categories are dictated by size, whereas, T3 and T4 are differentiated essentially by whether the structure being invaded is amenable to an uncomplicated surgical resection. Specifically, invasion of parietal pleura, chest wall, diaphragm, phrenic nerve, mediastinal pleura, parietal pericardium, main stem bronchus 2 cm or more distal from the carina or presence of a separate nodule within the same lobe are all considered T3 lesions. Invasion of the mediastinum, great vessels, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, esophagus, vertebral body, carina, or a separate nodule in a different ipsilateral lobe are all lesions that are considered T4.

With regards to lymph nodal spread, the classification is based upon the sequential drainage of the pulmonary lymph node basin. Hilar and intrapulmonary nodes are considered N1, ipsilateral paratracheal and subcarinal nodes are N2, and N3 corresponds to any contralateral and/or scalene/supraclavicular nodes. These nodal classifications are of extreme importance in the management of lung cancer as they largely dictate the treatment course to be selected for the majority of patients who are in a position to achieve a cure. Hence, the efforts placed into accurate lymph node staging by the treating team are of utmost importance to deliver the ideal customized treatment plan for each patient. Such careful staging is of particular importance when advanced disease is suspected due to the futility and potential harm of surgical resection in certain clinical scenarios. In order to deliver the most appropriate and beneficial modalities of treatment clinicians must use all means to obtain the most accurate staging possible.

As in any TNM staging system, spread to a distant organ is considered M1 disease. However, in the most recent edition of the AJCC lung cancer staging system, two specific clinical scenarios were reclassified into the M1 category. The presence of pleural nodules or pleural carcinomatosis has always been considered unresectable stage IV disease; yet, the presence of a pericardial or pleural effusion was previously considered a T4 lesion. Now, such effusions have been upstaged to M1a due to the extremely high likelihood that they are malignant in nature. This change is aimed to warn clinicians that significant prudence ought to be exercised in patients with diagnosed lung cancer who are found to have an effusion, so as to prevent resections in patients who have the associated dismal prognosis.6 Indeed, many patients with lung cancer and a concomitant pleural effusion will have a malignant effusion. Nevertheless, cases do occur where such effusions are benign in nature. Some potential examples would be patients with cardiogenic or parapneumonic effusions due to a recent infectious process. As a result, current recommendations focus on a combination of expert clinical judgment as well as repeatedly negative cytology from pleural fluid specimens prior to pursuing surgical treatment in patients with lung cancer and an associated effusion.

On the contrary, the presence of a nodule in the contralateral lung was downstaged to M1a to reflect the slightly improved prognosis of these patients as compared to those with distant disease. Nevertheless, this difference may be due to incorrect classification of synchronous primaries versus metastatic spread—a difference that can be difficult to make even with the use of molecular diagnostics. It is therefore critical for surgeons to maintain close communication with experienced pathologists in order to make every effort to delineate the nature of each lesion.

These two stages of disease, although representing advanced malignancy, are heterogeneous with respect to disease burden, treatment, and outcomes. Taken as a whole, patients with stage III and IV NSCLC have a poor prognosis. Even so, a clear distinction exists between stage IIIA NSCLC as compared to stage IIIB and IV lung cancer. Stage IIIA patients are candidates for curative intent therapy largely due to the more limited extent of lymph node spread in this cohort. As a result, the 5-year survival for stage IIIA disease is in the range of 19% to 24% for clinical IIIA (cIIIA) and pathological IIIA (pIIIA) disease, respectively. Even within stage IIIA clear lines can be drawn between patients with locally advanced disease (T3–4, N0–1) and those with N2 disease. Moreover, within patients with N2 disease prognosis is distinctly different for those with microscopic N2 versus single station N2 versus multistation bulky N2 disease. These differences are discussed in greater detail in the section on the management of IIIA disease.

Conversely, patients with IIIB disease have a uniformly dismal survival ranging from 7% to 9% for clinical and pathological stage, respectively. Patients with stage IV disease, as one would expect have even worse 5-year survival in the range of 2% with 6 months of median survival. Interestingly, those patients with stage IV disease who underwent resection and have pathological staging have a relatively better 5-year survival at 13% with 17 months of median survival. This finding is due to the highly selected patients who have isolated metastatic disease who undergo curative intent therapy despite what is technically stage IV disease.

Most patients will be referred for surgical consultation with a tissue diagnosis; however, not infrequently the treating surgeon will be called upon to recommend the ideal method to obtain tissue for definitive diagnosis. As with the treatment of any malignancy, a tissue diagnosis is paramount to all that follows. In the context of advanced lung cancer, one might expect that there is ample tumor bulk from which to obtain tissue; yet, with the advent of minimally invasive endoluminal platforms the algorithm used to arrive at a tissue diagnosis presents numerous subtleties and has evolved considerably over recent years. The first step in a case of suspected lung cancer is an adequate CT scan. While, screening programs for lung cancer have demonstrated that low-dose noncontrast CT scans are adequate, once a mass is identified and cancer suspected, a high-resolution contrast CT scan is required to delineate the anatomy and detect the presence or absence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The advent of PET scans has been of value in the diagnostic workup of lung cancer. Although not definitively required, the added information it provides is helpful. Lesions with high specific uptake values (SUV) are suggestive of a malignant process and PET scanning can shed light on the status of mediastinal lymph nodes.

From this point, determining the highest yield method of obtaining tissue with the lowest risk for complications can be a complicated task. The majority of patients with stage III or higher disease will have a bulky lung mass that is easily amenable to transthoracic needle guided aspirate (TTNA). However, not infrequently, the lung mass may be small or very central or the lung excessively emphysematous presenting a high risk for postprocedure persistent pneumothorax. Bronchoscopy is an important part of the diagnostic workup for a patient with lung cancer and is even more relevant when dealing with its more advanced forms. Bronchoscopy allows for the evaluation of the bronchial mucosa bilaterally and can determine the extent of bronchial invasion if present. Furthermore, bronchoscopy is an excellent means of obtaining tissue particularly when the mass is large and central. The addition of endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial fine needle aspirate (EBUS-TBNA) has extended the reach of standard bronchoscopy in terms of obtaining tissue for diagnosis. Beyond standard bronchoscopy and EBUS, navigational bronchoscopy, where an electromagnetic field placed beneath the patient is coupled to CT reconstructed imaging of the bronchial tree, allows the image-guided placement of biopsy forceps deep within distal bronchioles such that peripheral tumors in patients who are not amenable to TTNA can be biopsied via a minimally invasive technique.

In the context of advanced stage lung cancer, the presence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy will frequently be noted on CT scan and/or PET scan. In these patients one can consider mediastinal evaluation combining biopsy for diagnosis and mediastinal staging within the same procedure. With the advent of EBUS-TBNA, both steps can be accomplished with this one procedure with a very low morbidity and high yield. When EBUS-TBNA fails or is not available and TTNA presents a prohibitive risk, standard mediastinoscopy is a perfectly reasonable and usually definitive approach.

Finally, some rare situations may require a surgical transthoracic approach in order to obtain tissue. Although it may be perfectly reasonable in early stage patients to utilize video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) techniques to obtain a surgical specimen for diagnosis and follow with a formal resection if a diagnosis of NSCLC is obtained, proceeding directly to VATS or thoracotomy in patients suspected to have advanced disease should be a last resort. Exceptions could include patients who have had negative mediastinal staging and who continue to have no tissue diagnosis but harbor a highly suspicious lung mass.

Due to the importance of targeted therapies in the management of NSCLC, it is worth mentioning the evolving need to submit biopsy specimens for molecular testing for such molecular targets as EGFR and ALK, in addition to the standard molecular markers for the diagnosis of NSCLC. Needle aspirates are amenable to such testing by preparing them in the form of a cell-block.

The philosophy to staging in patients with suspected advanced lung cancer is similar to that in early stage lesions with emphasis on some key features. Extensive staging is required to make the difference between forms of advanced lung cancer that remain amenable to curative intent therapy versus those where treatments aimed at balancing survival advantage with improved quality of life are more appropriate. The combination of a diagnostic CT scan and PET scan provide excellent staging of the extent of local disease. In addition to providing important information regarding the mediastinum, PET scans help assess for the presence of extrathoracic disease. It should be noted that the resolution of PET scanning is limited to lesions greater than 6 mm in dimension, particularly when dealing with lesions that exhibit low SUVs. Hence, suspicious lesions on CT may require additional correlative imaging to rule out distant metastasis. Specific examples include small nodules found in the liver or adrenals on CT that can be better characterized with either ultrasound or MRI. In addition, patients with central tumors and who have suspected or confirmed mediastinal lymphadenopathy should undergo a brain MRI to rule out the possibility of brain metastases.

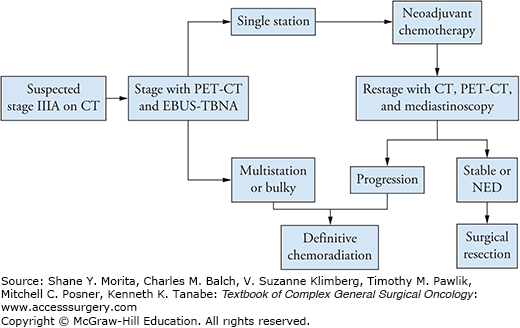

When CT/PET scan and brain MRI are negative for extrathoracic disease, but mediastinal lymphadenopathy is suspected, staging is aimed toward resolving the difference between a stage IIIA versus IIIB lesion. The critical difference to be made is essentially the presence of positive N3 lymph nodes. N3 status is defined by the presence of contralateral nodes and/or supraclavicular/scalene nodes. The presence of palpable cervical lymphadenopathy (supraclavicular/scalene) can often be easily assessed using transcutaneous fine needle aspirate (with or without ultrasound guidance). A positive aspirate yields a rapid diagnosis and immediately determines that the patient is not a surgical candidate. In more equivocal situations, EBUS-TBNA or mediastinoscopy are the preferred approaches. In a patient with stage IIIA disease who is being considered for surgical resection, we recommend that the mediastinum be staged initially with EBUS-TBNA. This allows surgical mediastinal staging after induction chemotherapy to confirm stability or regression of disease and hence candidacy for surgical treatment (Fig. 61-1). Although specific series in expert centers have shown that EBUS-TBNA has an equivalent false negative rate as compared to mediastinoscopy, such results are likely not applicable to all centers.7 The standard of care for mediastinal staging remains mediastinoscopy largely due to its broad availability. Given the limited value of surgical intervention in patients with IIIB disease, we recommend that surgeons demonstrate definitively IIIA status and the absence of N3 disease. When such a situation is suspected by imaging, repeat mediastinal staging by mediastinoscopy even after a negative EBUS-TBNA is a very reasonable approach.

Despite being locally advanced disease and generally a heterogeneous group, patients with stage IIIA disease should be considered curable and receive treatment aimed to that effect. The disease biology within this group can vary considerably. Stage IIIA now includes patients with large tumors and limited lymph node involvement (T4N1) as well as patients with very small lesions and more extensive lymph node involvement (T1N2). While this oddity should not alter the ultimate goal of therapy given the similarities in prognosis, the associated clinical findings can be misleading to the inexperienced clinician and can lead to suboptimal treatment plans. Treatment plans should take this fact into consideration and be tailored to the biology of the disease and to the presentation of the patient (Table 61-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree