BACKGROUND

Once the care of the newborn is over and the ostensibly “healthy” baby of a mother with hyperglycemia during pregnancy is discharged to his/her devoted family, the long wait begins. It is now 25 years since it was clearly established that children of diabetic Pima Indian women who had diabetes during pregnancy were themselves more likely to become obese1 and to develop diabetes.2 This phenomenon had been established previously in animal models3 and was soon observed in children of women with either Type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes.4,5

OBESITY

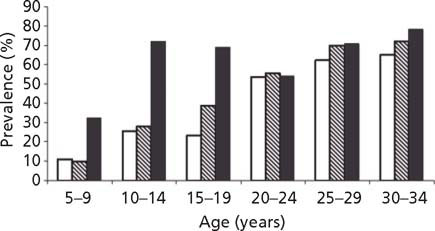

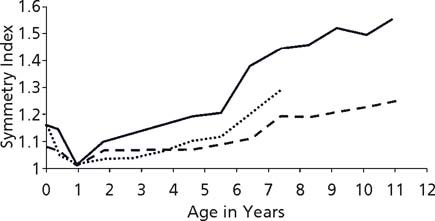

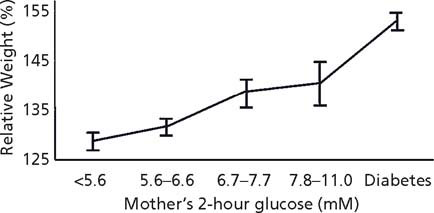

Among the Pima Indians of Arizona, a population with high rates of Type 2 diabetes, the weight centiles and the rates of obesity were significantly higher among offspring whose mothers had had diabetes during pregnancy than among offspring whose mothers either had not developed diabetes or developed it after the pregnancy (Fig. 25.1). 1,6,7 Although offspring of diabetic women were, on average, larger for gestational age at birth than were offspring of women without diabetes or of women who developed diabetes later in life, large birthweight was not a prerequisite for the development of obesity by 5–9 years of age. Even normal birthweight offspring of diabetic women were likely to be obese throughout childhood.8 This is in contrast to a study in predominantly Caucasian children from Rhode Island who were aged 4–7 years.9 Normal birthweight offspring of women with gestational diabetes were, if anything, less likely to be overweight than controls, while large for gestational age offspring were more obese by age 4 years and became increasingly obese by age 7 years. Data from Chicago demonstrated that offspring of women with Type 1 or gestational diabetes had a faster than expected growth during the fi rst 7 years of life.4 A direct comparison of data from the Pima and Chicago studies showed that, after the age of 2 years, even though the Pima children were heavier for their height, the two populations of children exposed in utero to maternal diabetes grew at similar rates (Fig. 25.2).10 After the age of about 5 years, the offspring of diabetic women in the Chicago study were heavier for height than the Pima children who had not been exposed in utero.

Fig. 25.1 Prevalence of severe obesity (weight ≥140% of age–sex–height-specific standard) by mother’s diabetes during and following pregnancy in 5–34-year-old Pima Indians. Open bars, offspring of non-diabetic women; hatched bars, offspring of women who were normal during pregnancy and later developed diabetes; solid bars, offspring of women with diabetes during pregnancy. (Reproduced with permission from Dabelea et al7.)

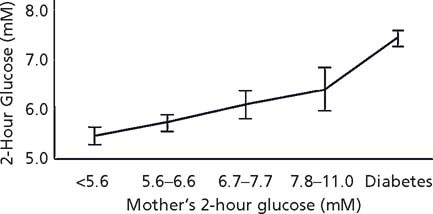

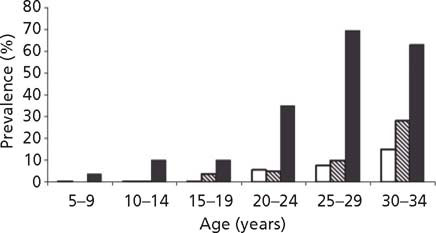

Among the Pima Indians, a fairly linear relationship between maternal glucose in the mother during pregnancy, even when in the normal range, and infant birth-weight was seen.11 This finding was confirmed recently in a sample of 25000 women followed in the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Study (HAPO).12 On follow-up of Pima children, a relationship between maternal glucose and both childhood obesity (Fig. 25.3) and childhood glucose tolerance (Fig. 25.4) was found across the full spectrum of glucose,13 and follow-up of children whose mothers were enrolled in the HAPO study should determine if a similar relationship emerges in other populations.14 Evidence suggesting that this may occur comes from the Early Bird Study.15 In that study, insulin resistance measured in the mothers 5 years following pregnancy, a value likely to be highly correlated with insulin resistance and fasting glucose during pregnancy, was directly related to the child’s weight.15

Fig. 25.2 Symmetry index (age–sex-specific weight centile divided by age–sex-specific height centile) in offspring of diabetic women from the Diabetes in Pregnancy Center in Chicago (dotted line) and the Pima Indian study (solid line). Also shown is the symmetry index offspring of non-diabetic Pima women (dashed line). (Reproduced with permission from Pettitt10.)

Fig. 25.3 Relative weight for height in 10–14-year-old offspring of Pima Indian women according to maternal glucose 2 hours after a 75-g glucose load during pregnancy. (Adapted from data included in Pettitt et al13.)

Fig. 25.4 Glucose concentration 2 hours after a 75-g glucose load in 10–14-year-old offspring of Pima Indian women according to maternal glucose 2 hours after a 75-g glucose load during pregnancy. (Adapted from data included in Pettittet al13.)

Fig. 25.5 Prevalence of diabetes by mother’s diabetes during and following pregnancy in 5–34-year-old Pima Indians. Open bars, offspring of non-diabetic women; hatched bars, offspring of women who were normal during pregnancy and later developed diabetes; solid bars, offspring of women with diabetes during pregnancy. (Reproduced with permission from Dabelea et al7.)

ABNORMAL GLUCOSE TOLERANCE

Compared with infants of non-diabetic Pima women, infants of Pima women who had Type 2 diabetes during pregnancy themselves developed Type 2 diabetes at younger ages, resulting in higher rates of diabetes throughout childhood.2 This finding was subsequently extended to age 34 years (Fig. 25.5) and remained significant.6,7 In an attempt to control more completely for shared environment and genetics, sibling pairs who were discordant both for Type 2 diabetes and for their exposure in utero to a diabetic pregnancy were analyzed. In three-quarters of cases, the sibling who was born later, and who was therefore exposed to diabetes in utero, was the sibling with diabetes.16 A similar analysis of sibling pairs, whose father had diabetes that developed after the first sibling but before the second sibling was born, showed no tendency for the second sibling to be affected more often than the first sibling.16

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is the phenotypic manifestation of a monogenic autosomal dominant mutation. Physiologically it is characterized by a defect in insulin secretion accompanied by normal insulin resistance. There are six known monogenic sub-types of MODY, of which that resulting from a mutation of the HNF-1α gene is one of the most common. Those born after their mother’s MODY was diagnosed manifested their glucose intolerance at a significantly younger age than those who were born before their mother’s disease developed (15.5 ± 5.4 vs 27.5 ± 13.1 years, respectively; p < 0.0001).17 A younger paternal age of onset of MODY was not associated with a younger age of onset in subjects who inherited MODY from their fathers. This again provides evidence that the diabetic intrauterine environment is associated with a younger age of onset of diabetes over and above genetic and other environmental factors.

By age 16 years, few of the children from the Chicago study, whose mothers had had either Type 1 or gestational diabetes during pregnancy, had themselves developed diabetes. However, almost 20% had impaired glucose tolerance.5 This was about 10-fold the rate of impaired glucose tolerance found in a control sample of children from the same population whose mothers had been normal during pregnancy.

More recently, examination of a cohort of young adults from Denmark confirmed the findings of the Chicago study in that offspring of women with Type 1 diabetes had rates of Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes (impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose) about three-fold that in the background population (11% vs 4%, respectively) and equal to rates among offspring of women with identifiable risk factors for gestational diabetes.18 Unlike the Chicago study, however, the Danish study found even higher rates of abnormal glucose tolerance among offspring of women with diagnosed gestational diabetes (21%) than among offspring of women with Type 1 diabetes.

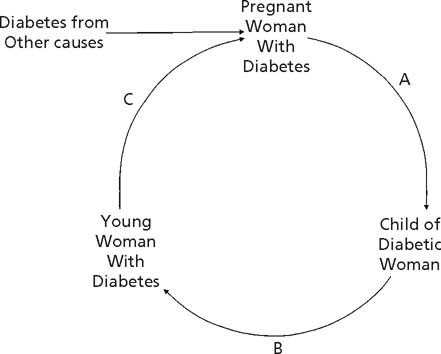

The phenomenon of diabetes in pregnancy resulting in more diabetes, or an earlier age of diabetes onset, in the offspring, represents a vicious cycle (Fig. 25.6).6,19 Many young women who were exposed to diabetes in utero have become obese and have developed diabetes by the time they enter their child-bearing years, thus perpetuating the cycle. The vicious cycle is also enhanced by new cases of diabetes in pregnant women because of other risk factors for gestational or pregestational diabetes. This can be seen most clearly in Type 2 diabetes among populations such as the Pima Indians. However, in MODY diabetes due to an HNF-1α gene mutation,17 a younger age of onset of diabetes means the young women will be more likely to have developed their disease by the time they have children, thus exposing the next generation to the diabetic intrauterine environment. Those offspring who have also inherited the HNF-1α mutation will then be at risk of an earlier age of onset of MODY diabetes. In the Chicago study,5 if further followup had been possible, it is likely that children with impaired glucose tolerance whose mothers had Type 1 or gestational diabetes would have developed diabetes or gestational diabetes by their early 20s, and thus exposed their offspring to diabetes in utero. In the Danish study, although not limited to pregnant offspring, the young adults were all of child-bearing age,18 so those with abnormal glucose tolerance or Type 2 diabetes constitute the next generation of young affected mothers.

Fig. 25.6 Vicious cycle of diabetes in pregnancy. Potential points of intervention are: A – to reduce the effect of the diabetic pregnancy on the offspring; B – to reduce the incidence of obesity and diabetes in the offspring of the diabetic woman; C – to control the diabetes prior to and during pregnancy to lessen the impact of the diabetes throughout gestation.