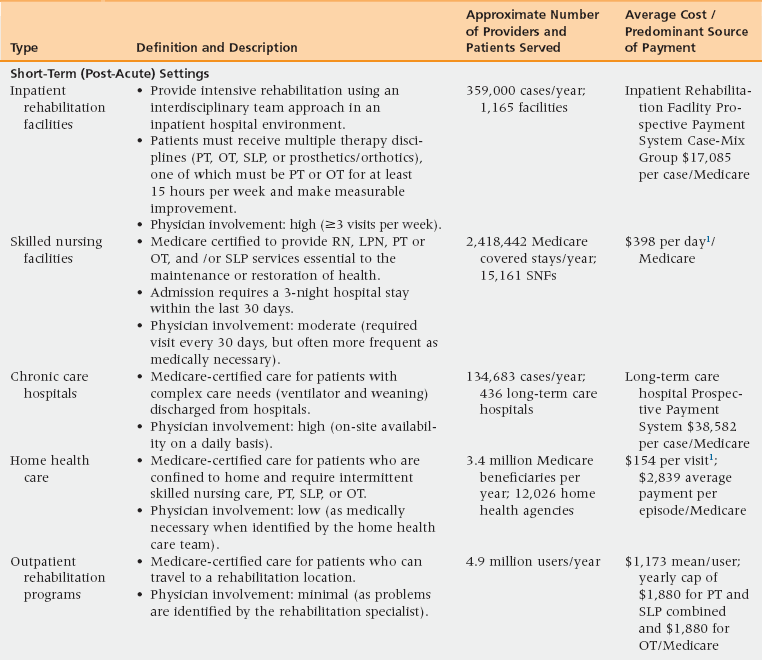

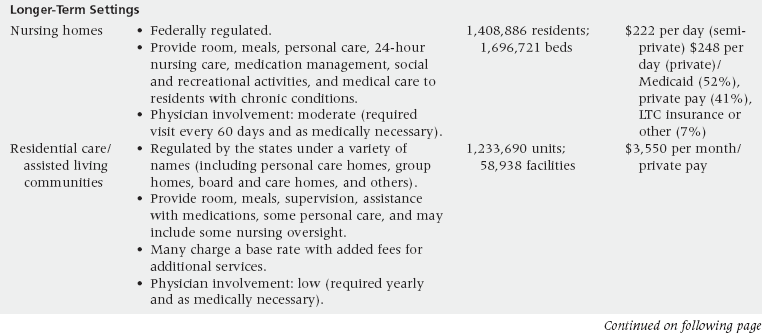

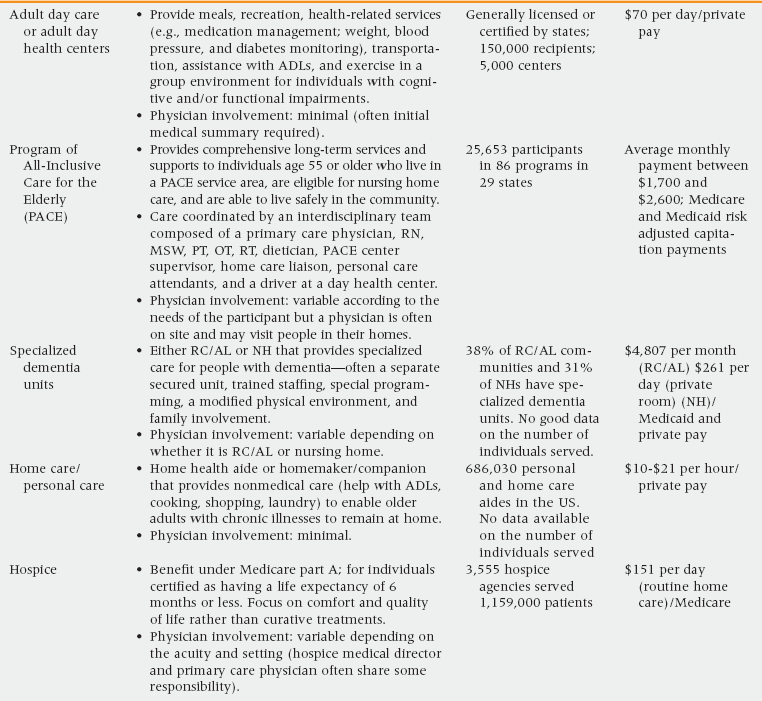

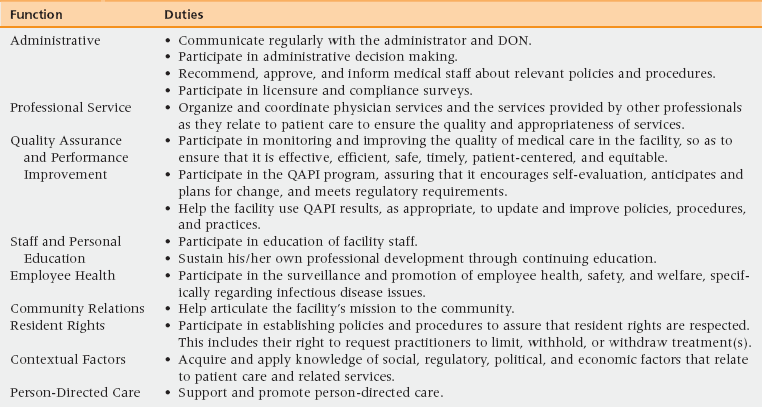

11 The Growing Need for Long-Term Care Medical Care Provider Practice Patterns in Long-Term Care Distinguishing between Dementia, Subacute Delirium, and Depression Physical and Pharmacologic Restraints Infections and Infection Control Measuring and Promoting Quality of Care and Quality of Life Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify the most common post-acute care and long-term care (LTC) options and list the services provided by each. • Accurately assess and recommend level of care needs, incorporating information from family, caregivers, therapists, and other members of the interprofessional team. • Describe the various LTC medical practice models and the role of physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in each. • Summarize the role of the medical director in the nursing home. • Identify and explain five common clinical challenges in LTC medicine. • Describe the process of evaluating decision-making capacity in older adults and apply shared decision making to clinical situations in LTC. • Describe how principles of quality improvement and individualized care can be applied in LTC. The United States is an aging society. The population older than age 65 is expected to grow at a rate of 107% from 2012 to 2050, much faster than the population as a whole.1 The population older than age 85, which is the group that most frequently uses long-term care (LTC), is projected to grow by 224% during the same time period.1 Older persons face a number of challenges that place them at risk for needing LTC: • Functional disability increases exponentially as people age. Thirty-seven percent of persons older than age 65, and up to 53% of those older than 85 years, have a functional limitation,1,2 and the presence of functional limitations is a major reason for needing LTC services. • The prevalence of dementia rises steeply with age, and having dementia is another major risk factor for needing LTC. The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias is 13% among all persons aged 65 and older and 45% among those aged 85 and older.3 In fact 75% of people with AD will be living in a nursing home by age 80 compared to only 4% for the general population.3 Furthermore, two thirds of older adults dying of dementia do so in a nursing home, a much higher figure than for other chronic diseases.3 Behavioral symptoms are a major reason that caregivers of older adults with dementia choose to place them in a nursing home.4 • Older persons are more likely to live alone than younger persons and, therefore, lack a potential live-in caregiver. Currently, one third of people older than age 75 live alone1 and 60% of women older than age 85 live alone.5 • Adult children often do not live near enough to their parents to enable them to provide the daily or weekly hands-on care needed. A recent study found that among current older adults with children, only one half had a child within 10 miles.5 Future older generations will have even fewer children who might care for them, as a consequence of lower fertility rates. • Poor caregiver health is another reason for entry into LTC.4 Sixty-one percent of family caregivers of people with AD report high or very high levels of emotional stress; 33% report symptoms of depression; and 43% report high to very high physical stress.3 Table 11-1 summarizes the most common types of LTC. As is evident from Table 11-1, LTC serves many older adults in a variety of settings. Indicators of the breadth of LTC services are these statistics from 2010: • There were 1.4 million occupied beds in 16,071 nursing homes across the United States.1 All told, 3.8 million persons were served by nursing homes, because many had short facility stays for post-acute care.6 • An additional 1.23 million older adults were living in residential care or assisted living facilities.1 • An estimated 42 million family caregivers were providing unpaid care.1 • A total of 3.4 million Medicare beneficiaries received home health care,7 and 2.5 million Medicaid participants received home- and community-based services or home health services.1 Nursing homes house two types of residents: (1) short-stay, post–acute care residents, who were admitted for rehabilitation, usually after a hospitalization, and (2) long-stay residents who are receiving chronic disease care or palliative care. About 4% of Medicare enrollees older than age 65 had a nursing home stay in 2009, with the rate highest among persons aged 85 and older (14%).2 Nursing home residents are mostly white (88%), female (66%), and elderly (median age 82.6).8 The racial make-up of the nursing home population should become more diverse in the future as the population of older adults changes in the United States.2 Nursing home residents commonly have multiple chronic illnesses; dementia is one of the most prevalent at 46%.1 Depressive symptoms, sensory impairment, pain, and functional impairment are also common. In addition, most LTC residents have functional limitations. For example, in 2009, 68% of all nursing home residents had three or more activity of daily living (ADL) limitations (bathing, dressing, eating, getting in/out of chairs, toileting) and 95% had at least one instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitation (using the telephone, housework, meal preparation, shopping, managing money).2 Residential care and assisted living communities have a variety of names, depending on state regulations, including assisted living residences, board and care homes, congregate care, enriched housing, homes for the aged, personal care homes, and shared housing. In 2010 there were 1,233,690 units in 58,938 RC/AL residences, most of which were private, for-profit settings.1,9 Half were small (4-10 beds), but these facilities served only 10% of the overall RC/AL population. The majority of residents (52%) lived in large (26-100 bed) or (29%) in extra-large (>100 beds) facilities.9 Nearly all RC/AL communities provide basic health monitoring, incontinence care, social and recreational activities, special diets, and personal laundry services.9 Most also offer transportation to medical appointments and case management, whereas social services, counseling, and physical and occupational therapy tend to be offered only by large RC/AL communities or indirectly through home care agencies.9 Residents are typically white (91%), female (70%), age 75 and older (81%), and have a median length of stay of 22 months.10 Over a third (38%) of residents receive assistance with three or more activities of daily living, of which bathing and dressing were the most common; and another 36% receive assistance with one to two ADLs.10 These demographic descriptors indicate that considerable overlap exists between the population of RC/AL communities and nursing homes. Nursing homes are required by law to have a medical director; RC/AL communities are not, but a few do have them. The medical director is a physician who oversees and guides care in a LTC facility.11 The primary functions are summarized in Table 11-2. TABLE 11-2 Functions and Duties of a Nursing Home Medical Director DON, Director of nursing; QAPI, quality assessment and performance improvement. Adapted from AMDA. The nursing home medical director: Leader and manager (White Paper A11). Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2011. Available at http://www.amda.com/governance/whitepapers/A11.cfm. Physicians who practice in nursing homes do so within a variety of practice models. The traditional model has been as an adjunct to an office-based practice. In the last decade new practice models have arisen: the LTC-only practice and the house-call practice. With these, there has been a call to recognize that nursing home medicine is emerging as a specialty in its own right, similar to the hospitalist.12 Physicians working in this specialty have been referred to as SNFists, nursing home physician specialists, or LTC specialists. The nursing home physician specialist spends a substantial portion of time in the delivery of nursing home care and is proficient in nursing home regulations and the medical management of common syndromes faced by nursing home residents. Nurse practitioners (NPs) provide primary care to nursing home residents as nursing home employees, as members of primary care practices, or as employees of health maintenance organizations. NPs are registered nurses who have a master’s degree and obtain certification through a national certifying examination or through state certification mechanisms. The NP scope of practice varies by state. In 10 states no physician involvement is required; however, 40 states give NPs the authority to prescribe only with physician oversight.13 Federal nursing home regulations require collaboration with a physician in all states. Physician assistants (PAs) function in much the same way as NPs in nursing homes. They are non-nurse providers whose training typically consists of 1 year of basic science classes and 1 year of clinical rotations. PAs must practice under the supervision of a physician, but they have the authority to prescribe in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.14 The PA scope of practice varies by state and is largely determined by the physician; most commonly, a physician can delegate to PAs anything that is within the physician’s scope of practice and the PA’s training and experience.14 Evercare is a Medicare Advantage program specifically for long-stay nursing home residents that extensively uses NPs or PAs. The NPs or PAs work as employees of the managed care company and provide more intensive primary care than is typical. They are assigned to work in specific nursing homes, usually one or two, carrying a caseload of approximately 100 residents.15 The nursing home residents continue to have their primary care physician, which Evercare pays on a fee-for-service basis, including payment for time spent in family or care-planning conferences (which is not ordinarily reimbursed under Medicare). The NP also educates the nursing home staff through formal and informal in-service training. Because the NP or PA is present in the nursing home frequently under the Evercare model, they monitor residents closely and develop relationships with the staff, which facilitates early identification of acute illnesses. Because they are salaried employees of the managed care company, Evercare NPs and PAs can spend more time in preventive and early intervention direct care that might not otherwise be reimbursed by Medicare. In addition, Evercare can pay the nursing home for “intensive service days,” when an ill resident might otherwise need to be hospitalized. As a result, Evercare sites have fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits than traditional care models, and Evercare enrollees have higher patient and family satisfaction with the care.15 Much of the care delivery in LTC occurs via telephone—more so than in other clinical settings. Many of the telephone calls occur after hours and on weekends to on-call providers who may not be familiar with the patient or the facility. Most telephone calls report a clinical problem. For example, in one study of a typical nursing home, the problems that were most frequently reported by phone were falls, pain, agitation, abnormal blood glucose, and fever, with the calls typically prompting a clinical action, such as ordering a medication or treatment, clinical observation by the nursing staff, or diagnostic studies.16 CNAs fill a critical role in the nursing home, providing most of the basic patient care. They assist residents with ADLs, provide skin care, take vital signs, answer calls for help, and are expected to monitor residents’ well-being and report significant changes to nurses. The 2004 National Nursing Assistant Survey (NNAS) found that the majority (92%) of CNAs were female with a high school or less education (74.4%) and a family income of less than $30,000.17 There was also considerable racial diversity, with 53% of CNAs being white, 38.7% African American, and 9.3% Hispanic or Latino in origin. Average age was 39 years, and 34% were 45 years or older. The average hourly pay rate was $10.36; 75% who were not covered by another source were enrolled in their employer health insurance plan. Most became CNAs because they like helping people, and only 10% said they would not become a CNA again; but 45% revealed that they might leave the facility in the next year because of poor pay or because they found a better job. Being a CNA is hard work; 56% had been injured at work in the previous year. Staff turnover is a major challenge facing nursing homes in the United States and is costly and a major factor contributing to quality problems. The average U.S. nursing facility staffing turnover rate was 40% in 2010, although in some states it was as high as 70%.1 Recommendations for increasing staff recruitment and retention include increased training, increased pay, the provision of health insurance benefits, and improving the work environment by nurturing positive relationships between CNAs and their supervisors, fostering respect among the workforce, and providing opportunities for advancement.18

Long-term care

The growing need for long-term care

Types of long-term care

Nursing homes

Residential care / assisted living (RC/AL) communities

Medical care provider practice patterns long-term care

Nursing homes

Long-term care