Surgery for anal cancer is usually reserved for patients with persistent disease or local recurrence after definitive chemoradiation therapy. Patients with local recurrence should be re-evaluated for evidence of metastatic disease using positron emission tomography–computed tomography, and the local anatomy should be delineated with MRI. Eligible patients should undergo tailored surgery with the aim of achieving an R0 resection. Management is best undertaken within a specialized multidisciplinary setting. Careful patient selection and shared decision making are paramount for achieving acceptable patient-centered outcomes.

Key points

- •

Less than 20% of patients suffer locoregional failure after chemoradiation therapy for anal cancer.

- •

Complete restaging with MRI pelvis and computed tomography–positron emission tomography followed by multidisciplinary tumor board discussion is required in all patients considered for surgery.

- •

The ability to achieve R0 resection with acceptable morbidity determines the potential for salvage surgery, which may involve extensive resection of perineal soft tissue and/or pelvic organs with subsequent reconstruction.

- •

In patients planned for curative resection, an R0 resection is ultimately achieved in the majority of patients (86%), with 5 year overall and disease-free survival of 60%.

- •

Careful patient selection, and shared decision making in a specialized multidisciplinary setting is paramount for achieving acceptable patient-centered outcomes.

Introduction

Chemoradiation therapy (CRT) is the standard of care in the primary treatment of anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with salvage surgery reserved for the less than 20% of patients who suffer locoregional failure with persistent disease (within 6 months) or recurrent disease (after 6 months). There are several factors that can predict failure, the most obvious being a higher T stage or N stage, with a reported one-third of patients with T4 or N3 disease developing a local recurrence. Of patients who develop locoregional failure, 75% involve the anus or rectum; 20% recur elsewhere in the pelvis outside the radiotherapy field, and less than 5% recur in the inguinal nodal basins.

A vital component for the management of these patients is early detection of recurrences. Because biopsy of the post-CRT scar is no longer routinely recommended because of poor yield, and there is no reliable tumor marker to measure, detection of recurrences is heavily reliant on detailed clinical follow-up. This entails a detailed physical examination with a digital rectal examination, anoscopy, and inguinal palpation for nodal involvement, as well as protocolized cross-sectional imaging for surveillance of more advanced disease.

If a local recurrence is detected, then complete restaging is required followed by multidisciplinary discussion and consideration for salvage surgery.

Introduction

Chemoradiation therapy (CRT) is the standard of care in the primary treatment of anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with salvage surgery reserved for the less than 20% of patients who suffer locoregional failure with persistent disease (within 6 months) or recurrent disease (after 6 months). There are several factors that can predict failure, the most obvious being a higher T stage or N stage, with a reported one-third of patients with T4 or N3 disease developing a local recurrence. Of patients who develop locoregional failure, 75% involve the anus or rectum; 20% recur elsewhere in the pelvis outside the radiotherapy field, and less than 5% recur in the inguinal nodal basins.

A vital component for the management of these patients is early detection of recurrences. Because biopsy of the post-CRT scar is no longer routinely recommended because of poor yield, and there is no reliable tumor marker to measure, detection of recurrences is heavily reliant on detailed clinical follow-up. This entails a detailed physical examination with a digital rectal examination, anoscopy, and inguinal palpation for nodal involvement, as well as protocolized cross-sectional imaging for surveillance of more advanced disease.

If a local recurrence is detected, then complete restaging is required followed by multidisciplinary discussion and consideration for salvage surgery.

Surgical technique

Preoperative Planning

History

A full account of the patient’s medical, surgical, and social history is obtained. Several points are of specific importance in the setting of locally recurrent anal cancer:

- •

Does the patient have pain, weight loss; leg swelling; neurologic, obstructive, and/or urinary symptoms; or gynecologic symptoms in females? Importantly, symptoms present at the time of diagnosis may have implications for resectability and prognosis.

- •

When and where were the primary CRT treatments undertaken? Details of doses, radiation fields, duration, and patient tolerance are required to enable planning of future CRT regimens.

- •

Review of histology.

- •

What is the patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, human papilloma virus (HPV) status, and details of immunization?

- •

What postoperative surveillance has the patient undergone so far? Details of serial examination, anoscopy, nodal assessment, and cross-sectional imaging are useful to indicate rate of progression.

- •

Review of systems to enable determination of medical fitness for further treatment.

- •

Social history including functional status, cognitive ability, quality of life, social support, and patient preferences are required to facilitate shared decision-making discussions.

Examination

Digital rectal examination to document the precise tumor location and extent, and to establish involvement of adjacent structures, as well as palpation of nodal basins is required. In female patients, a per-vaginal examination can also help to determine vaginal involvement. Rectal and vaginal examination may have to be performed in the operating room under general anesthetic if discomfort does not permit adequate assessment in the outpatient setting, and this may also allow confirmatory biopsy if this has not been done. Finally, assessment of the abdominal wall, looking specifically for incisional hernia and the state of the rectus abdominis muscle on both sides is important if there is likely to be a need for soft tissue reconstruction. For the same reason, the state of the perineum after radiotherapy should also be assessed.

Imaging

The purpose of cross-sectional imaging is to establish 2 important facts regarding the anatomy of the recurrence that will determine whether curative treatment is an option:

Whether there is distant metastatic disease

Local resectability (predicted R0 resection)

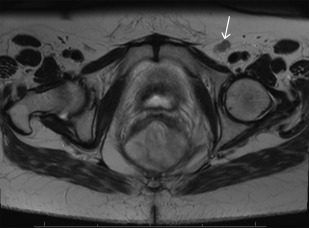

Multiphase contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is commonly used for the detection of metastatic tumor deposits. In some institutions, including the authors’ institution, fluorodeoxyglucose [18F] positron emission tomography with CT (PET/CT) is utilized routinely as part of the initial assessment of recurrent disease, as there is some evidence that it alters management in a significant subset of patients ( Fig. 1 ). High-resolution MRI with or without diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) is the current standard of care for evaluation of pelvic resectability. Good-quality T2-weighted images are essential (see Fig. 1 ), preferably accompanied by standardized reporting with specific comment on the involvement of any pelvic viscera and nodal disease ( Fig. 2 ).

Multidisciplinary considerations

After the previously described assessment and investigations are performed, the patient’s case is reviewed at a multidisciplinary tumor board meeting, and the options for management are discussed. In the absence of distant metastatic deposits, treatment with curative intent mandates surgical resection of all known disease. Most commonly this will mean an abdominoperineal resection, but treatment can range from repeat wide local excision (rarely) to complete pelvic exenteration with multivisceral resection, sacrectomy, and reconstruction.

Patients with locally recurrent anal cancer with pelvic disease should only be offered exenterative surgery if all of the following criteria are fulfilled:

- 1.

Complete R0 resection is technically possible based on imaging.

- a.

Absolute technical contraindications to resection are: unresectable extrapelvic disease, para-aortic node involvement, bilateral sciatic nerve involvement, circumferential bone involvement, lumbar spine involvement (above L5/S1).

- b.

Relative contraindications are: tumor extension through the sciatic notch, encasement of external iliac vessels, and high sacral involvement (sacrectomy above S2/S3 junction is controversial but can be performed in selected centers).

- a.

- 2.

The patient is medically fit to undergo the procedure.

- 3.

The patient is cognitively able to engage in a shared decision making discussion, and give reasonable informed consent.

If the patient is not a candidate for exenterative surgery, then a palliative surgical option would be proximal fecal diversion if soiling or feculent vaginal discharge is an issue. A loop sigmoid colostomy via a minimally invasive surgical approach is ideal if this is technically achievable.

Informed consent

After multidisciplinary tumor board recommendations have been finalized, a face-to-face meeting between the primary colorectal surgeon and the patient accompanied by a support person (such as a close family member) is scheduled to facilitate formal discussion and informed consent. There may me multiple options offered to the patient, and each of these needs to be discussed fully, outlining the benefits and risks. The consent discussion should also include details of planned stomas and the possibility of the surgeon finding unexpected metastatic disease intraoperatively that is unresectable and would lead to the procedure being aborted. A shared decision-making process on the part of the attending surgeon and the patient is required and should be clearly documented.

It is usual for the patient to also discuss management with a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and any other surgical services that are expected to be involved during the operation. Involvement of a cancer nurse specialist or care coordinator, an ostomy nurse, and relevant allied health staff such as cultural support workers and interpreters is prudent.

Medical optimization

Given the magnitude of the surgery to be undertaken, the management of all relevant medical comorbidities should be optimized, with the help of perioperative care physicians and the involvement of anesthetists, preferably with experience in this type of surgery. In patients who require it based on screening assessments, preoperative nutritional support and prehabilitation programs should be undertaken. There is a high risk of intraoperative hemorrhage, and any anticoagulants the patient is on preoperatively should be managed accordingly. Wound healing or lack thereof is a common postoperative concern, and preoperative smoking cessation is actively encouraged, especially if flap closure is planned.

Coordination of multidisciplinary team

Depending on the anatomy of the surgery to performed, a multidisciplinary team of surgeons may be required. Anticipated involvement based on preoperative assessment should result in the patient being seen and consented by the relevant service ahead of time in the outpatient setting. Pelvic and perineal defects may require flap closure by a plastic surgeon. Less commonly, such as in the setting of pelvic disease require exenteration, involvement of urologists, vascular surgeons, and orthopedic surgeons may be required.

The patient should be marked by an experienced stoma nurse to facilitate assessment of stoma location in standing, supine, and sitting positions, and when the patient is in his or her usual clothes. Given the lengthy nature of this type of surgery, it is important that delays are minimized by effective coordination.

Preparation and Patient Positioning

The patient is usually placed in modified Lloyd-Davies position, with provision for undertaking part of the procedure via a perineal or posterior approach if necessary. Calf compression devices and precautions against pressure areas are routinely used. A folded towel or roll may be placed under the sacrum to improve access to the perineum. The whole perineum including the anal region and vagina in females is prepped. Prepping and draping should take into account not only the needs of the primary surgeon, but also the optimal exposure and preparation for the other members of the multidisciplinary surgical team. For example, if an inguinal lymphadenectomy is to be performed, then the inguinal region needs to be exposed appropriately.

Surgical Approach

Exploration and/or wide local excision

The first step is digital rectal examination and vaginal examination in women to re-establish the anatomy of the disease. If the recurrence is localized without significant anal sphincter involvement, then a perineal-only approach such as a repeat wide local excision with or without flap closure may be all that is required. However, if the disease is more advanced, then an abdominoperineal resection is usually required.

Abdominal phase

An exploratory laparotomy is performed first. All 4 quadrants of the abdomen, including the liver, the diaphragm, and the small and large bowel and their mesentery are visually inspected and palpated. A finding of unexpected metastatic disease that is unresectable should be confirmed with intraoperative frozen section, and the procedure should be abandoned save for palliative defunctioning stoma if deemed beneficial by the operating surgeon. In the absence of unresectable metastatic disease, the next step is a complete adhesiolysis, followed by mobilization of the sigmoid colon and left colon. The left ureter is identified and preserved. The splenic flexure is not routinely mobilized, but this may be required for added length to facilitate end colostomy formation. The inferior mesenteric artery is then identified and isolated. This is secured and divided where feasible for length and the ends ligated with a heavy braided absorbable suture. The inferior mesenteric vein is identified and isolated. This is secured and divided where feasible for length, with the ends ligated with a heavy braided absorbable suture. A high tie of the inferior mesenteric vessels is not usually required from an oncological point of view, but may be needed to achieve adequate length on the stoma, particularly in overweight patients.

Pelvic phase

Rectal dissection is undertaken in the total mesorectal excision (TME) plane. The point of division of the inferior mesenteric artery leads the surgeon into the plane posteriorly, and dissection is continued distally as far as possible. Lateral dissection and anterior dissection are then completed, and circumferential TME is completed down to the pelvic floor.

Exenteration

In patients with more advanced disease, extended resection may be required, most commonly including posterior colpectomy for women or a partial prostatectomy for men. In the 20% of patients with pelvic recurrence, pelvic exenteration is required. Identification of any normal uninvolved planes and dissecting within these are usually the best place to start. Dissection then continues from easier and softer tissues toward more difficult and rigid areas, with wider margins taken as necessary. Identification of the ureters and a decision regarding whether one or both can be preserved can often be the defining step in this operation. Ureteric catheters are a useful aid to assist in palpation and identification of the ureters, which, if free, can be slung with a vascular loop and preserved. Options for ureteric reconstruction include uretero-uretorostomy with or without psoas hitch, ureteric reimplantation, or Boari flap repair. If the situation is not directly reconstructable, then the urologist may proceed with a radical cystectomy with out without prostatectomy and subsequent ileal or colonic conduit reconstruction after the specimen is removed.

In cases with extensive lateral pelvic sidewall involvement, iliac vessel identification and dissection are required. If the common, external, or internal iliac arteries or veins are invaded by tumor, then en bloc resection and reconstruction by a vascular surgeon may be considered to achieve R0 resection, although this is done highly selectively. First, the internal iliac artery and its branches are ligated distal to the superior gluteal artery to minimize buttock claudication and preserve supply to any potential gluteal flaps. Lymph node dissection is performed including nodal tissue overlying the aortoiliac bifurcation down to the origin of the internal iliac. Proximal control and distal control of the internal iliac vein are achieved, and smaller branches are divided prior to division of the main trunk. The lateral and middle sacral vein branches are also ligated and divided, and dissection is continued along the pelvic sidewall bilaterally down to the pelvic floor, with the dissection completed from below if required. Extended lateral pelvic sidewall excision, including resection of the sciatic nerve, has also been described.

En bloc sacrectomy can also be performed if necessary with orthopedic surgeon involvement. Resections above S3 require conversion to the prone position, whereas below S3 a combined abdominal/perineal approach can be used. All gluteus muscular attachments to the posterior aspect of the coccyx and sacrum are dissected free up to a point above the planned site of sacral transection. The sacrococcygeal ligaments are divided off the sacrum, and the anterior sacrum is scored with diathermy at the level of planned transection. Division is possible with the patients still in the supine position using 2 osteotomes, one placed posterior to the sacrum to protect the skin and the other anteriorly for transection. For sacrectomy above the level of S3, temporary or permanent closure of the abdomen is required prior to turning the patient prone, and the sacrectomy is completed from below.

If possible, an omental pedicle flap based on the right gastroepiploic artery is fashioned and used to fill the dead space in the pelvis. A rectus abdominis muscle-only flap can also be used to achieve this. At least 1 intra-abdominal drain is often used and placed in the pelvis as well.

Perineal phase

This component of the resection is highly variable, and dependent on the extent of local perineal disease. The general over-riding principle is wide local excision of the perineal component of the recurrent tumor with clear margins, which often requires complete excision of the anal sphincter complex. In women, vaginal recurrence is common, and therefore, posterior vaginectomy should be considered. At times anterior extension to include en bloc resection of the urogenital organs is warranted.

Intraoperative radiotherapy

Any margins that are not obviously macroscopically clear are confirmed with intraoperative frozen section. Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) is administered selectively with consultation with the radiation oncologist if any resection margins are microscopically positive (R1) based on intraoperative frozen pathology assessment, or if the margins were negative but 2 mm or less. At the authors’ center, IORT is administered using high-dose rate iridium-192 brachytherapy using a Harrison–Anderson–Mick applicator, with a dose of 10 to 15 Gy at 1 cm from the radiation source.

Ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy

A small subset of patients recur in the ilioinguinal nodal basins, and can undergo lymph node dissection with good outcomes. A folded towel is placed behind the pelvis on the affected side, with the ipsilateral hip slightly flexed and laterally rotated to maximize exposure. If a laparotomy was already performed, then iliac lymph node dissection can be performed through this incision. Inguinal lymphadenectomy requires a separate incision over the femoral triangle. If a laparotomy has not been performed, then an S-shaped incision is made from the anterior superior iliac spine to the apex of the femoral triangle with the oblique part of the incision in the groin crease. This allows access to both the iliac and inguinal compartments. The inguinal ligament is identified and divided, and this incision is extended vertically into the external oblique aponeurosis. The spermatic cord is retracted medially, and the internal oblique/transversus muscles are divided. The inferior epigastric vessels are ligated and divided. The peritoneum, bladder, and rectum are retracted medially. The superior limit of dissection is the common iliac artery overlying the sacroiliac joint. Lymph node dissection begins laterally on the pelvic sidewall and progresses medially, with all lymphatic tissue surrounding the external iliac vessels, obturator canal, and internal iliac vessels retrieved.

Dissection then continues inferiorly into the inguinal compartment progressing from superficial tissues to deep. The great saphenous vein is identified and ligated flush onto the femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction. Dissection of all lymphatic tissue from the lateral border of sartorius muscle to the medial border of gracilis muscle is performed. Centrally, a block of nodal tissue is dissected off the femoral artery and vein, which are skeletonized to the floor of the femoral triangle. Femoral canal nodes are included in this part of the specimen. Inferiorly, the dissection continues down to the apex of the femoral triangle, at which point the more proximal aspect of the great saphenous vein is ligated and divided.

Soft tissue reconstruction

The size of the defect depends on the extent of the resection (determines anteroposterior and lateral dimensions), and the patient’s body habitus (determines depth). The complexity of the reconstruction can be compounded by the presence of stomas, previous incisions, and hernias, as well as vascular supply to tissue flaps or lack thereof. Close consultation with experienced plastic surgical services is therefore required at all stages.

Flap closure of perineal defects reduces wound complications compared with attempts at primary closure, particularly after radiation treatment. It is possible to use absorbable or biological mesh to reconstruct the pelvic floor, but this technique may still require additional soft tissue coverage, as primary skin closure is not always possible without tension. Selection of which flap to use is based on the size of the defect, the availability of tissue, the characteristics of the patient, and the local expertise available. The most common technique utilized for perineal reconstruction is the vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (VRAM) based on the inferior epigastric artery, which is a robust flap that usually affords significant tissue bulk. Harvesting of this flap leaves a defect in the anterior abdominal wall that usually requires repair with synthetic mesh or component separation techniques. Other options include: gracilis muscle flaps, inferior gluteal artery myocutaneous flaps (IGAM), gluteal fold flaps, anterolateral thigh flaps, and full-thickness local advancement flaps. In female patients, vaginal reconstruction can be attempted using modifications of the previously mentioned flaps, or including local rotation flaps such a modified Singapore flap. A Sartorius muscle flap may be used to cover the femoral triangle compartment if this was dissected.

Immediate Postoperative Care

All patients are managed in a high-dependency unit setting immediately after surgery and transitioned to standard ward care as able. Principles of enhanced recovery after surgery are applied as closely as possible, while taking into account the magnitude of surgery undertaken, and the unique considerations that go along with this. Wound complications are common in the setting of flap closure, particularly given the previously irradiated tissue in this setting. This issue needs to be anticipated and actively managed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree