Lobular neoplasia (LN) is characterized by a dysfunctional E-cadherin-catenin axis, and loss of E-cadherin plays a causative role in the typical morphology of LN cells. LN is both a nonobligate precursor and a risk indicator of invasive breast cancer, and in particular, of invasive lobular carcinoma. Despite the evidence supporting the precursor role of LN, its impact on clinical management has been a matter of controversy, and conservative management remains the mainstay of treatment. In this article, an update is provided on the pathology and genetics of LN, and the management of these lesions in surgical practice is discussed.

Key points

- •

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) are uncommon pathologic findings, representing part of a spectrum of epithelial proliferations referred to as lobular neoplasia (LN). LN can be considered both a nonobligate precursor of invasive breast cancer and a marker of increased risk.

- •

Loss of E-cadherin expression, caused by mutations, deletions, and methylation, is one of the defining features of LN; however, aberrant E-cadherin expression can be observed in a few lesions.

- •

A diagnosis of LCIS confers a long-term cumulative risk of a subsequent breast cancer that averages 1% to 2% per year and remains steady over time, resulting in relative risk of breast cancer that is 8-fold to 10-fold greater than the general population risk. ALH is associated with a relative risk of breast cancer 4-fold to 5-fold greater than the general population.

- •

A diagnosis of LN made by surgical excision does not require further surgical intervention; there is no indication to document margin status in specimens that contain only LN. The presence of LN in a lumpectomy specimen or at the margin is not a contraindication to breast conservation and does not require re-excision.

- •

Although routine surgical excision after a core biopsy diagnosis of LN is supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the management of patients with this diagnosis requires a multidisciplinary approach. Excision is routinely recommended when there is radiologic-pathologic discordance and when the diagnosis indicates a less common histologic variant of LN.

- •

Patients with LN should be informed of their increased risk of breast cancer and counseled regarding both medical and surgical risk-reducing options.

Introduction

According to the current World Health Organization classification of breast lesions, lobular neoplasia (LN) is defined as a term that encompasses the entire spectrum of atypical epithelial lesions that originate in the terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU) of the breast and is characterized by a population of dyshesive cells, which expand the lobules and acini of the TDLUs, and may involve the terminal ducts in a pattern known as pagetoid spread. These lesions were traditionally described under the terms lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), which refer to the degree of involvement of the acinar structures of a given TDLU.

The first description of a lesion with features consistent with those currently used to define LCIS dates to 1919, when Ewing described an “atypical proliferation of acinar cells.” However, the main characteristics of LCIS were not thoroughly documented until the seminal study by Foote and Stewart in 1941, in which the term LCIS was coined to refer to a spectrum of “noninfiltrative lesions of a definitely cancerous cytology.” Based on the frequent identification of LCIS in association with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), and following the analogy of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), Foote and Stewart hypothesized that the neoplastic cells of LCIS would still be contained within a basement membrane and that this lesion would constitute a precursor of breast cancer development, leading to the recommendation for mastectomy. Emerging data throughout the 1970s from Haagensen and colleagues and others showed that the risk of breast cancer development after a diagnosis of LCIS was lower than that expected for a direct precursor lesion (approximately 1% per year) and was conferred equally to both breasts, generating controversy regarding the significance of these lesions and leading to disparate recommendations for management, ranging from observation only to bilateral mastectomy.

The term ALH was coined in 1978 to refer to a less-prominent in situ proliferation composed of cells cytologically identical to those of LCIS, which were associated with a significantly lower risk of subsequent breast cancer development (approximately one-half of the risk associated with LCIS). However, because the distinction between LCIS and ALH, which is based on quantitative rather than qualitative differences between the lesions (described later), often proves challenging in diagnostic specimens, Haagensen and colleagues put forward the term LN to refer to the entire spectrum of these in situ lesions, including ALH and LCIS.

In current practice, a diagnosis of LN is perceived as a risk factor for the subsequent development of breast cancer. However, observational data suggesting that the risk of breast cancer development after a diagnosis of LN is higher in the ipsilateral than in the contralateral breast, and compelling molecular data that show that ALH and LCIS are clonal neoplastic proliferations that commonly harbor the same genetic aberrations as those found in adjacent invasive cancers, have reinstated the notion that ALH and LCIS are both nonobligate precursors and risk indicators of invasive breast cancer. In this article, the clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics of LN are revisited, and the impact of recent developments on the management of these lesions is discussed.

Introduction

According to the current World Health Organization classification of breast lesions, lobular neoplasia (LN) is defined as a term that encompasses the entire spectrum of atypical epithelial lesions that originate in the terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU) of the breast and is characterized by a population of dyshesive cells, which expand the lobules and acini of the TDLUs, and may involve the terminal ducts in a pattern known as pagetoid spread. These lesions were traditionally described under the terms lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), which refer to the degree of involvement of the acinar structures of a given TDLU.

The first description of a lesion with features consistent with those currently used to define LCIS dates to 1919, when Ewing described an “atypical proliferation of acinar cells.” However, the main characteristics of LCIS were not thoroughly documented until the seminal study by Foote and Stewart in 1941, in which the term LCIS was coined to refer to a spectrum of “noninfiltrative lesions of a definitely cancerous cytology.” Based on the frequent identification of LCIS in association with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), and following the analogy of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), Foote and Stewart hypothesized that the neoplastic cells of LCIS would still be contained within a basement membrane and that this lesion would constitute a precursor of breast cancer development, leading to the recommendation for mastectomy. Emerging data throughout the 1970s from Haagensen and colleagues and others showed that the risk of breast cancer development after a diagnosis of LCIS was lower than that expected for a direct precursor lesion (approximately 1% per year) and was conferred equally to both breasts, generating controversy regarding the significance of these lesions and leading to disparate recommendations for management, ranging from observation only to bilateral mastectomy.

The term ALH was coined in 1978 to refer to a less-prominent in situ proliferation composed of cells cytologically identical to those of LCIS, which were associated with a significantly lower risk of subsequent breast cancer development (approximately one-half of the risk associated with LCIS). However, because the distinction between LCIS and ALH, which is based on quantitative rather than qualitative differences between the lesions (described later), often proves challenging in diagnostic specimens, Haagensen and colleagues put forward the term LN to refer to the entire spectrum of these in situ lesions, including ALH and LCIS.

In current practice, a diagnosis of LN is perceived as a risk factor for the subsequent development of breast cancer. However, observational data suggesting that the risk of breast cancer development after a diagnosis of LN is higher in the ipsilateral than in the contralateral breast, and compelling molecular data that show that ALH and LCIS are clonal neoplastic proliferations that commonly harbor the same genetic aberrations as those found in adjacent invasive cancers, have reinstated the notion that ALH and LCIS are both nonobligate precursors and risk indicators of invasive breast cancer. In this article, the clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics of LN are revisited, and the impact of recent developments on the management of these lesions is discussed.

Anatomic pathology and classification

ALH and Classic LCIS

Before introducing the histologic features of LN, it should be emphasized that the terms ALH, LCIS, and LN do not have histogenetic implications and do not imply that these lesions originate in the breast lobules. The term LCIS was chosen by Foote and Stewart to emphasize the histologic similarities between the cells of LCIS and those of frankly invasive lobular carcinoma, and it was acknowledged in their seminal study that LCIS would likely originate in the TDLUs and small ducts.

From a histologic standpoint, LN encompasses a spectrum of noninvasive lesions that affect the TDLUs, which are characterized by a constellation of architectural and cytologic features. In its classic form, LN is characterized by variable enlargement and distention of the acinar structures by a neoplastic population of monomorphic, dyshesive, small, round, or polygonal cells, often with inconspicuous cytoplasm. However, the lobular architecture is largely maintained, and the neoplastic cells show the characteristic dyshesiveness and a regularly spaced distribution. Intracytoplasmic lumina and vacuoles, sometimes containing a central eosinophilic dot (known as magenta body), are usually found. Mitotic figures and necrosis are not commonly found in classic LN. Pagetoid spread within the affected TDLU or to adjacent ducts, whereby the neoplastic cells extend between intact overlying epithelium and underlying myoepithelial layer and basement membrane, is frequently observed.

In the classic forms of LN, some degree of cytologic variation can be observed, and 2 cytologic subtypes have been described, namely type A cells, which are small, dyshesive cells, with scant cytoplasm and nuclei approximately 1.5 times the size of that of a lymphocyte, and type B cells, which show a slightly greater degree of variation, have more abundant and often clear cytoplasm, have nuclei that are slightly bigger than those of type A cells (ie, approximately 2 times the size of that of a lymphocyte), and show mild to moderate nuclear atypia; nucleoli, in type B cells, are also indistinct or absent ( Table 1 ). Although the subclassification of LN into these cytologic subtypes has not been shown to be of clinical usefulness and does not have a direct correlation with the risk of invasive breast cancer development, it is by no means a mere academic exercise. It serves as a reminder that some cytologic variation can be observed in bona fide cases of classic LN, and these features should not be overinterpreted as representing the pleomorphic variant of LCIS (described later).

| Type of Carcinoma | Nuclear Characteristics | Cytoplasm | Cell Cohesiveness | Necrosis and Calcifications | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCIS type A | Small and bland nuclei (1.5× the size of a lymphocyte) Nuclear grade 1 (rarely 2) Inconspicuous nucleoli | Scant | Dyshesion present but often inconspicuous | Necrosis absent and infrequent calcifications | ER and PR positive (>95%) HER2 negative |

| LCIS type B | Slightly larger nuclei (2× the size of a lymphocyte) Nuclear grade 1 or 2 Small nucleoli may be present | Moderate | Conspicuous dyshesion | Necrosis absent and infrequent calcifications | ER and PR positive (>95%) HER2 negative |

| PLCIS | Large and pleomorphic nuclei (4× the size of a lymphocyte) Predominant nuclear grade 3 Nuclei present | Moderate to abundant | Conspicuous dyshesion | Necrosis and calcifications often found | ER and PR often positive, but often at lower levels than in type A/B HER2 occasionally amplified |

| Apocrine PLCIS | Large and pleomorphic nuclei (4× the size of a lymphocyte) Nuclear grade 3 Nuclei present Vesicular chromatin | Abundant with fine eosinophilic granules | Conspicuous dyshesion | Necrosis and calcifications often found | ER and PR often negative or low levels HER2 often amplified |

LN has traditionally been subclassified into ALH and LCIS, based on quantitative rather than qualitative features of the lesions. A diagnosis of LCIS requires more than half the acini in an involved lobular unit to be filled and distended by the characteristic LN cells, leaving no central lumina. In objective terms, lobular distention is defined as the presence of 8 or more cells in the cross-sectional diameter of an acinus. ALH is defined as a less well-developed and less-extensive lesion, in which the characteristic cells only partly fill the acini, less than half of the acini of the TDLU are involved, and there is minimal or no distention of the lobule.

The arbitrary and subjective nature of this classification system, which is also dependent on the extent of sampling of a given lesion, frequently leads to high levels of inter-observer and intra-observer variability, creating difficulties in routine clinical practice. Yet, this classification system has been widely adopted given the lower risk of breast cancer development conferred by ALH than by LCIS (described later).

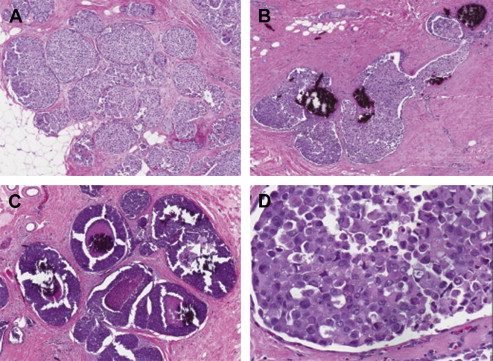

Pleomorphic LCIS

In addition to the classic forms of LN, several variants of LN have also been described. Of potential clinical significance is the pleomorphic variant, first described in its pure form by Sneige and colleagues under the name of pleomorphic LCIS (PLCIS). This variant is characterized by pleomorphic cells that are substantially bigger than those of classic LN, and by more abundant, pink, and often finely granular cytoplasm. Features of apocrine differentiation are frequently found but are not essential for a diagnosis of PLCIS. The pleomorphism observed in cells of PLCIS is greater than that found in type B cells; PLCIS nuclei are more than 4 times the size of a lymphocyte nucleus, show more overt pleomorphism and atypia, and the nucleoli are conspicuous ( Fig. 1 , see Table 1 ). Although PLCIS also distends the acinar structures of TDLUs, it is not uncommon to find lesions with central, comedo-type necrosis and microcalcifications. However, necrosis and microcalcifications are not required for a diagnosis of PLCIS.

Recognition of the pleomorphic subtype of LCIS is important, given that its histologic features (namely, the combination of marked pleomorphism, comedo-type necrosis, and calcification) can lead to difficulty in differentiating between PLCIS and DCIS, and, potentially, overtreatment; however, data regarding the natural history of PLCIS are limited, and the management of these lesions is still largely based on empiricism. Although some advocate for a more aggressive approach in the management of patients with PLCIS, with treatment recommendations akin to those for DCIS, this approach is supported only by molecular studies, which have shown that PLCIS shares many similarities with pleomorphic ILC, not by long-term outcome studies showing the risk of subsequent cancer development. Other variants of LN, with a biological and clinical significance that also remains to be determined, include the apocrine, histiocytoid, rhabdoid, endocrine, and amphicrine variants of classic LCIS, and the apocrine variant of PLCIS.

Lobular Intraepithelial Neoplasia

The lobular intraepithelial neoplasia (LIN) classification system was proposed as a unifying terminology to encompass both classic and pleomorphic LN. In this system, LIN lesions are subclassified by morphologic criteria and clinical outcome into 3 grades (LIN 1, LIN 2, and LIN 3), with LIN 3 representing PLCIS and additional LN variants at the higher end of the spectrum, including those variants with extensive lobule involvement and necrosis, and lesions composed of signet ring cells. This system presupposes that the risk of invasive carcinoma development is related to increasing grade of LIN, a notion that is not supported by level I evidence. This classification system has the merit of sparing women from a diagnosis of carcinoma in the case of LCIS; however, it is supported by limited evidence and has not been endorsed in the latest edition of the World Health Organization classification.

Molecular features and pathophysiology

Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of invasive breast cancers and their precursors are leading to a better understanding of the molecular pathways involved in the evolution of breast cancers and their impact on the clinical behavior of these lesions. It is accepted that estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative breast cancers are fundamentally different diseases, with distinct patterns of gene expression changes and, to an extent, different repertoires of genetic aberrations. Classic invasive lobular lesions are low-grade ER-positive breast cancers, characterized by recurrent losses of 16q and gains of 1q and 16p. Molecular studies of LN, showing similar findings, provide evidence to suggest that ALH and LCIS are nonobligate precursors of invasive cancer and have also been instrumental in highlighting the role of E-cadherin inactivation in the development of lobular lesions.

Phenotypic Characteristics of LN

LN, in its classic forms, is typically characterized by strong expression of ER-α (ERα), ER-β (ERβ), and progesterone receptor (PR); low proliferation indices as defined by Ki-67, and lack of expression of HER2 and p53 ( Table 2 ), features that are consistent with those of ER-positive breast cancers with a less aggressive clinical behavior (ie, luminal A).

| LN Encompassing ALH and LCIS | PLCIS | Apocrine PLCIS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER | + | +/– | –/+ |

| PR | + | +/– | –/+ |

| HER2 | Not amplified | Occasionally amplified | Often amplified |

| E-cadherin | Negative a | Negative a | Negative a |

| β -catenin | Negative b | Negative b | Negative b |

| p120 catenin | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic |

| GCDFP-15 | –/+ | +/– | + |

| p53 | –/+ | +/– | +/– |

| Ki-67 | Low | Intermediate to high | Often high |

a Abnormal discontinuous or fragmented staining patterns or cytoplasmic dots can occasionally be observed.

The phenotypic characteristics of PLCIS are more varied; although most of these lesions do express ER and PR, their expression is usually at lower levels, and truly ER-negative cases of PLCIS have been documented. HER2 gene amplification and HER2 overexpression can also be found in a subset of PLCIS, and intermediate to high Ki-67 labeling indices, usually higher than those of classic LCIS, are a common feature of these lesions.

The apocrine subtype of PLCIS, which is composed of cells with overt apocrine cytology and which express gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, a marker of apocrine differentiation, are frequently found to have HER2 gene amplification and high proliferation rates; however, the criteria to differentiate between PLCIS and apocrine PLCIS remain a matter of controversy.

E-Cadherin and Related Proteins in LN

Both classic and pleomorphic forms of LN are characterized by a dysfunctional E-cadherin-catenin adhesion complex. E-cadherin is encoded by the CDH1 gene, which maps to 16q22, a locus often lost in LN and ILCs. E-cadherin, a transmembrane adhesion molecule found in adherens junctions, mediates homophilic-homotypic adhesion between epithelial cells and interacts with p120 catenin and β-catenin through its intracytoplasmic domain. When E-cadherin is lost in breast epithelial cells, cytoplasmic, and occasionally nuclear, accumulation of p120 catenin is observed, as is loss of β-catenin membranous expression; however, nuclear accumulation of β-catenin or activation of the canonical Wnt pathway is not found.

LN, both classic and pleomorphic, and ILCs lack or show marked downregulation of E-cadherin expression in more than 95% of cases (see Table 2 ). This molecular aberration is believed to be the cause of the characteristic dyshesiveness of LN and PLCIS cells. LN, PLCIS, and ILCs have also been shown to have abnormal patterns of expression of the other components of the cadherin-catenin complex, including lack of β-catenin membranous expression and cytoplasmic expression of p120 catenin. This knowledge has provided a wealth of ancillary markers for the differentiation of LN from its mimickers, in particular, for the distinction between LN and cases of solid low-grade DCIS. E-cadherin has been advocated for the classification of low-grade solid in situ proliferations with indeterminate features, such that lesions with positive E-cadherin staining should be considered as DCIS, those lacking E-cadherin expression should be classified as LCIS, and lesions composed of populations of E-cadherin–positive and E-cadherin–negative cells should be classified as mixed.

Although E-cadherin has proved to be a useful ancillary marker in diagnostic breast pathology, its indiscriminate use has led to misconceptions about the diagnostic value of this marker, particularly when a detailed inspection of staining is not performed. Aberrant expression patterns of E-cadherin, in the form of fragmented, focal, or beaded patterns, are not uncommonly observed. Although the prevalence of E-cadherin positive classic LN is yet to be established, anecdotal cases of classic LN with strong and continuous E-cadherin expression have been reported. In addition, approximately 10% to 16% of ILCs may be E-cadherin positive. Hence, membranous expression of E-cadherin in a lesion with clear-cut histologic features of LN should not preclude a diagnosis of LN. In these cases, β-catenin and p120 catenin may provide additional evidence to differentiate between LN and DCIS.

One of the most frequent genetic aberrations in low-grade ER-positive breast lesions is 16q loss, which occurs in most cases and is believed to be an early event in the neoplastic development of LN and low-grade DCIS. Although the target gene of 16q deletions in DCIS and IDC remains to be identified, in LN and ILC, the CDH1 gene has been shown to be the target. Loss of E-cadherin expression in LN, PLCIS, and ILCs stems from a combination of genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptional mechanisms affecting the CDH1 gene. Loss of 16q is often accompanied by CDH1 inactivating mutations, CDH1 homozygous deletions, or CDH1 gene promoter methylation, which result in biallelic silencing of the gene and loss of protein expression.

The study of CDH1 mutations has had a dramatic impact on our understanding of LN. First, the identification of identical CDH1 gene mutations in LN and synchronous ILC components from individual patients has provided direct evidence to show that some LN and ILCs are clonally related and that at least some LNs are precursors of ILC. In addition, conditional mouse models in which CDH1 gene mutations and p53 knockout were targeted in an epithelium-specific manner have provided strong circumstantial evidence to suggest that CDH1 gene inactivation is a driver of the lobular phenotype.

In addition to the genetic mechanisms reported to result in CDH1 gene inactivation, transcriptional changes that result in E-cadherin dysfunction have been reported. Transforming growth factor β pathway activation, and upregulation of SNAIL, SLUG, and ZEB1 , have been shown to result in downregulation of E-cadherin in lobular lesions. In addition, transcriptomic and immunohistochemical analyses have shown that there is a stepwise decrease of the messenger RNA and proteins of the E-cadherin and catenin families from LCIS to ILC concurrent with upregulation of TWIST and SNAIL.

Despite the clear role of loss of E-cadherin in the biology of LN, germline mutations of the CDH1 gene do not seem to be a major cause of familial LN. Although CDH1 germline gene mutations account for approximately 30% of cases of hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma, which are also composed of dyshesive cells and have a growth pattern similar to that of lobular carcinomas, germline truncating mutations of CDH1 have been shown to play a limited role in familial LN and ILC. Although ILCs have been reported in the context of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome, patients with truncating CDH1 germline gene mutations presenting solely with LN or ILCs are rare.

Genomics of LN

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array analyses of LN have shown that these lesions are clonal and neoplastic, that their most frequent copy number changes include loss of material from 16p, 16q, 17p, and 22q, and gain of material from 6q.

Genomic studies have also corroborated the observations in regards to the potential precursor nature of LN made from CDH1 gene sequencing. SNP array analyses of LN and invasive breast cancers have provided direct evidence that classic LCIS and many adjacent synchronous lesions, including ER-positive DCIS, ILC, and ER-positive IDC, are often clonally related. Clonal patterns between LN and ILC have also been observed in CGH studies, and in studies based on mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy and mitochondrial gene mutation analyses.

Genomic analyses of PLCIS and pleomorphic ILCs have established 2 important points. First, that PLCIS and pleomorphic ILCs are variants of classic LN and classic ILC, given that they harbor the hallmark genetic features of classic LN and ILCs, including loss of 16q, and gain of 1q and 16p. However, they do have more complex genomes and amplification of genomic loci involving oncogenes associated with an aggressive phenotype, such as MYC (8q24) and HER2 (17q12). One study in which PLCIS was subclassified into those with and without apocrine features suggested that only apocrine, but not conventional PLCIS, would have more complex patterns of chromosomal copy number aberrations than classic LCIS. However, this observation requires further validation, given that the histologic features required to distinguish between PLCIS and apocrine PLCIS have yet to be fully defined. Second, these studies have shown that PLCIS and pleomorphic ILC are genetically related entities, highlighting the potential precursor role of PLCIS in the development of pleomorphic ILC akin to the relationship between LCIS and ILC.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree