Lobular Carcinoma in Situ and Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) are related lesions most often characterized by a proliferation of small, loosely cohesive, neoplastic epithelial cells within the terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs); they differ only in the degree of TDLU involvement by the neoplastic cells. These lesions have traditionally been considered markers of a generalized (bilateral) increase in breast cancer risk. However, recent evidence suggests that at least some examples represent direct breast cancer precursors.

Some authors have advocated grouping ALH and LCIS together under the single term lobular neoplasia.1 The purported advantages to this approach are that it removes the word “carcinoma” from the diagnosis of an in situ lesion and that it eliminates the need to make the morphologic distinction between ALH and LCIS, which in some cases is problematic and somewhat arbitrary. However, the major disadvantage of this approach is that it combines into one category lesions that, although parts of a spectrum, differ in the magnitude of the associated breast cancer risk.2 Therefore, it remains clinically useful to continue to distinguish ALH from LCIS.3

LOBULAR CARCINOMA IN SITU

LCIS is a relatively uncommon lesion. In the premammographic era, it was found in 0.5% to 3.6% of otherwise benign breast biopsies. Although this lesion is more frequently encountered in biopsies performed because of mammographic microcalcifications, the histologically identified calcifications are most often located in normal breast tissue adjacent to areas of LCIS.4 The age range in which LCIS is encountered is broad, but it is most common in younger women. The mean age at diagnosis is usually reported to be between 44 and 46 years and 80% to 90% of women are premenopausal. Multicentricity in the ipsilateral breast has been identified in 60% to 80% of cases. Bilaterality has been reported in 25% to 30%.4

Clinical Presentation

In the premammographic era, LCIS was always an incidental finding in breast tissue removed because of another abnormality. Most LCIS identified in biopsies performed because of mammographic microcalcifications is also incidental. However, in a small proportion of cases, the mammographically identified microcalcifications are associated with the LCIS itself.5,6

Gross Pathology

There are no grossly identifiable abnormalities attributable to LCIS.

Histopathology

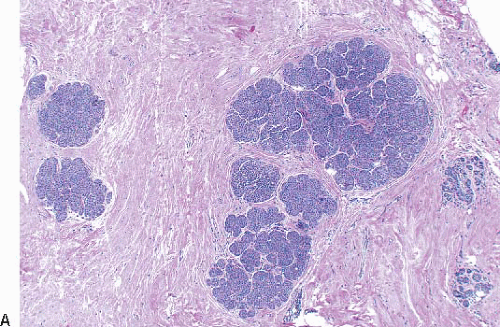

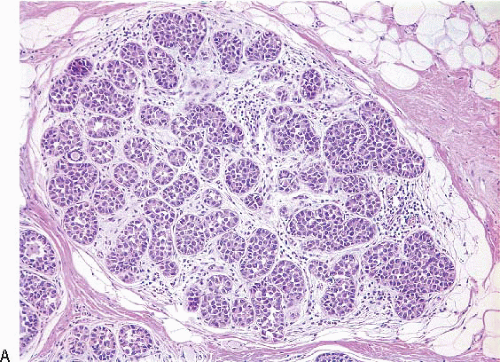

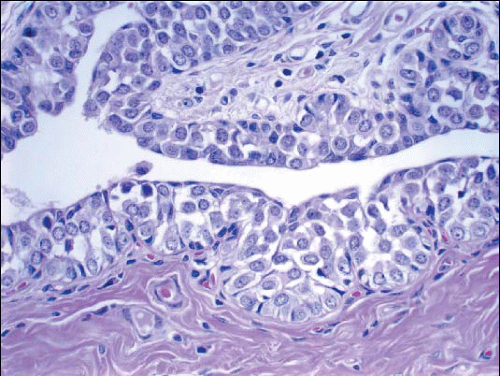

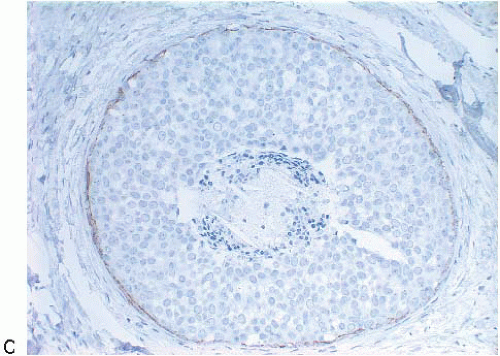

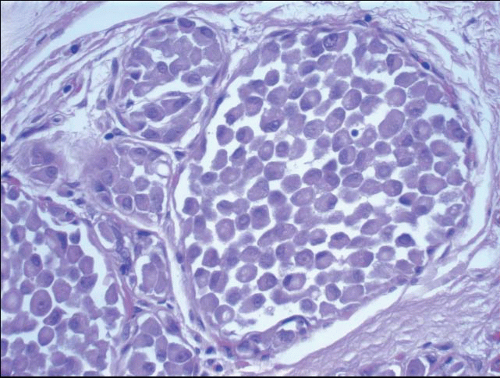

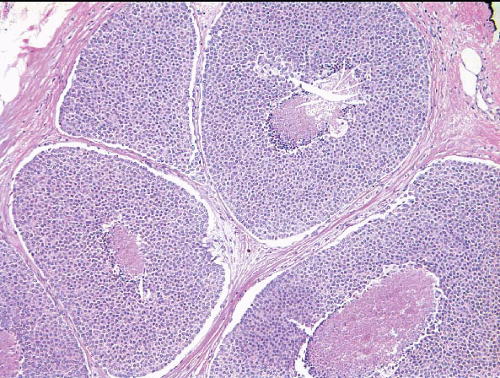

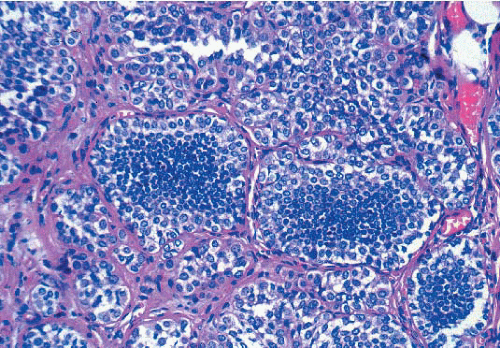

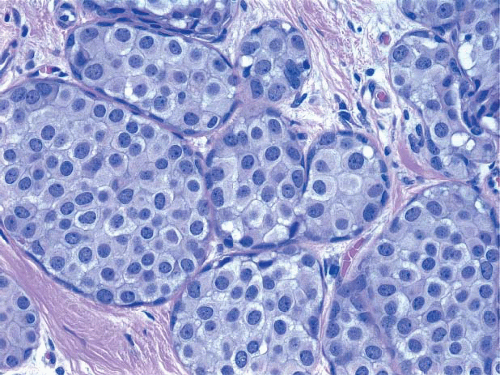

In TDLUs involved by the classical form of LCIS, the acini are filled with and distended by a solid proliferation of small cells with small, uniform, round-to-oval nuclei that have relatively homogeneous chromatin and nucleoli that are inconspicuous to absent. Mitoses are infrequent (Fig. 5.1, e-Fig. 5.1). At least half of the acini in a lobule must be filled with and distended by this cell population in order to qualify for a diagnosis of LCIS; lesser degrees of involvement warrant a diagnosis of ALH (see the subsequent text). The assessment of lobular distension is to some degree subjective and there is no gold standard by which to determine its presence. One practical approach is to compare the caliber of involved acini with that of uninvolved acini, although the caliber of the latter may be quite variable in some cases. The cells of LCIS are most often loosely cohesive. In some cases, residual lumina may be observed in the involved acini; however, the LCIS cells themselves do not polarize around these extracellular lumina. This form of LCIS, with small cells with small,

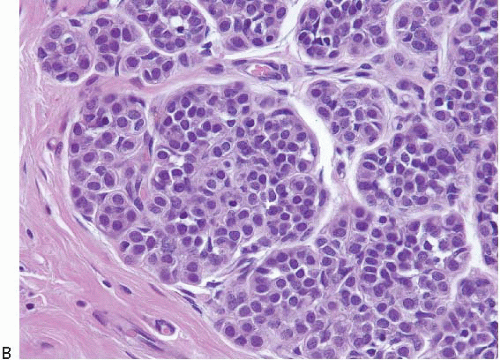

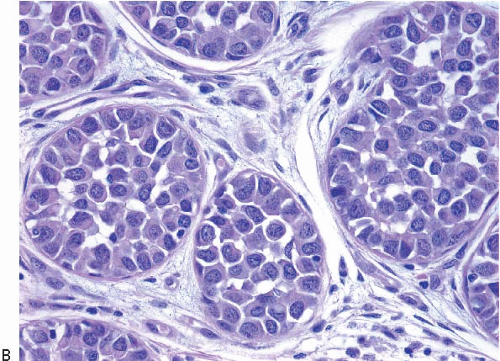

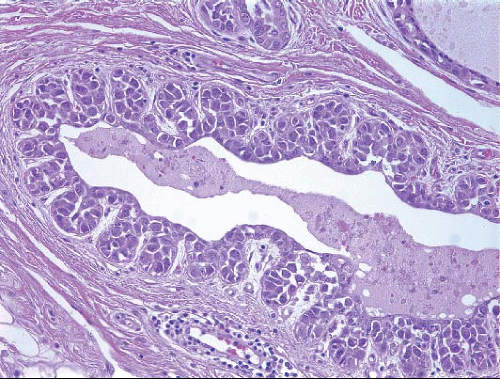

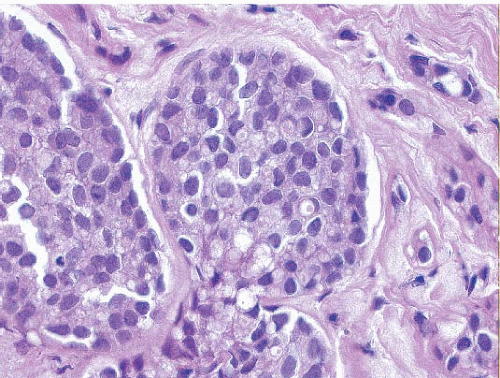

uniform nuclei, was referred to as type A by Haagensen et al.1 However, Haagensen, Azzopardi, and others noted that some LCIS lesions may be characterized by cells that show more abundant cytoplasm and slightly more variation in cell and nuclear size and shape and by the presence of nucleoli; these have been referred to as type B cells (Fig. 5.2, e-Fig. 5.2).1

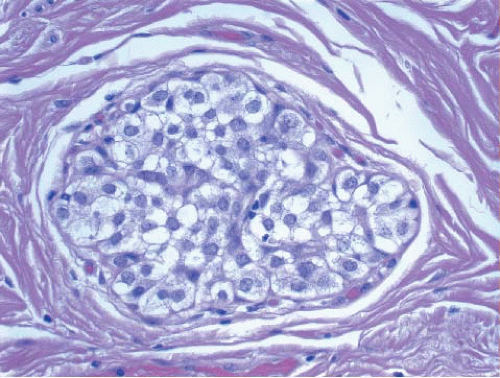

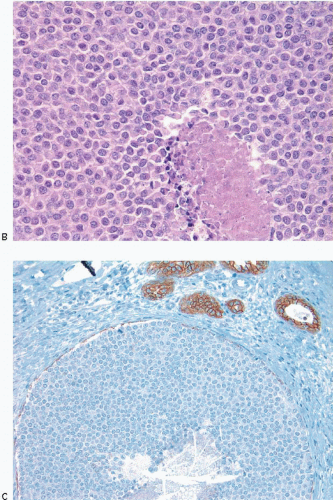

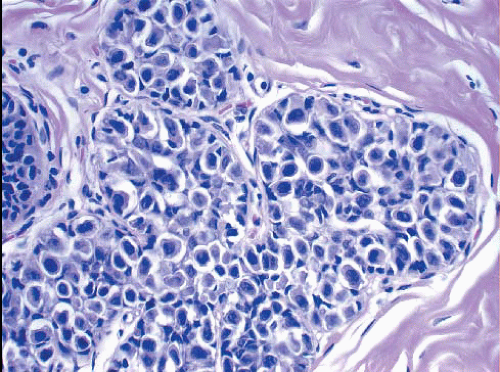

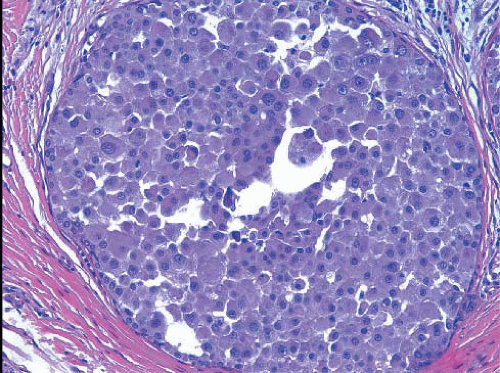

In some instances, type A and type B cells coexist within a single space (Fig. 5.3). Regardless of cell or nuclear size, the cytoplasm of LCIS cells is typically pale to lightly eosinophilic. In almost all cases of LCIS, at least some cells contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles that may contain an eosinophilic mucin globule (Fig. 5.4). These vacuoles may be so subtle that special histochemical stains for mucin are required for their demonstration. At the other end of the spectrum, the vacuoles may be large enough to

produce signet ring cell forms (Fig. 5.5). The cells of LCIS typically show loss of cell membrane expression of the adhesion molecule E-cadherin (see the subsequent text).7, 8, 9 and 10

uniform nuclei, was referred to as type A by Haagensen et al.1 However, Haagensen, Azzopardi, and others noted that some LCIS lesions may be characterized by cells that show more abundant cytoplasm and slightly more variation in cell and nuclear size and shape and by the presence of nucleoli; these have been referred to as type B cells (Fig. 5.2, e-Fig. 5.2).1

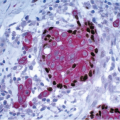

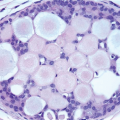

In some instances, type A and type B cells coexist within a single space (Fig. 5.3). Regardless of cell or nuclear size, the cytoplasm of LCIS cells is typically pale to lightly eosinophilic. In almost all cases of LCIS, at least some cells contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles that may contain an eosinophilic mucin globule (Fig. 5.4). These vacuoles may be so subtle that special histochemical stains for mucin are required for their demonstration. At the other end of the spectrum, the vacuoles may be large enough to

produce signet ring cell forms (Fig. 5.5). The cells of LCIS typically show loss of cell membrane expression of the adhesion molecule E-cadherin (see the subsequent text).7, 8, 9 and 10

FIGURE 5.3 Lobular carcinoma in situ with a mixture of smaller, central type A cells and larger, peripheral type B cells. |

In about three-quarters of the cases, the cells of LCIS involve the terminal ducts and/or extralobular ducts.3 The growth of the cells within these ducts may be solid but is more often pagetoid (i.e., the LCIS cells are

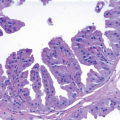

insinuated between the duct basement membrane and the native ductal epithelial cells) (Fig. 5.6, e-Fig. 5.3). Some ducts involved by LCIS have irregular outer contours with the formation of protruding buds that produce an appearance resembling a “clover leaf” (Fig. 5.7, e-Fig. 5.4).3 Although some authors believe that ductal involvement alone is sufficient for a diagnosis of LCIS, others render a diagnosis of ductal involvement by ALH when diagnostic changes of LCIS are not concurrently identified in the lobules.11

insinuated between the duct basement membrane and the native ductal epithelial cells) (Fig. 5.6, e-Fig. 5.3). Some ducts involved by LCIS have irregular outer contours with the formation of protruding buds that produce an appearance resembling a “clover leaf” (Fig. 5.7, e-Fig. 5.4).3 Although some authors believe that ductal involvement alone is sufficient for a diagnosis of LCIS, others render a diagnosis of ductal involvement by ALH when diagnostic changes of LCIS are not concurrently identified in the lobules.11

FIGURE 5.4 Lobular carcinoma in situ. Many of the cells contain small intracytoplasmic vacuoles, some of which contain an eosinophilic globule. |

FIGURE 5.5 Lobular carcinoma in situ. In this case, the cells have signet ring cell morphology, with large intracytoplasmic, mucin-filled vacuoles that displace the nuclei to the cell periphery. |

The outer layer of myoepithelial cells is retained in the acini and ducts involved by LCIS, but may be attenuated. In some cases, scattered myoepithelial cells are admixed with the neoplastic epithelial cells within the involved spaces.

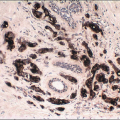

In addition to involving lobular acini and ducts, LCIS may involve a variety of lesions including usual ductal hyperplasia, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), fibroadenomas, intraductal papillomas, columnar cell lesions/flat epithelial atypia, benign sclerosing lesions (such as sclerosing adenosis, radial scars, and complex sclerosing lesions), and collagenous spherulosis (Fig. 5.8, e-Fig. 5.5). The involvement of these lesions by LCIS

may be solid, pagetoid, or both, and the resulting patterns can create diagnostic problems (see the Differential Diagnosis section).

may be solid, pagetoid, or both, and the resulting patterns can create diagnostic problems (see the Differential Diagnosis section).

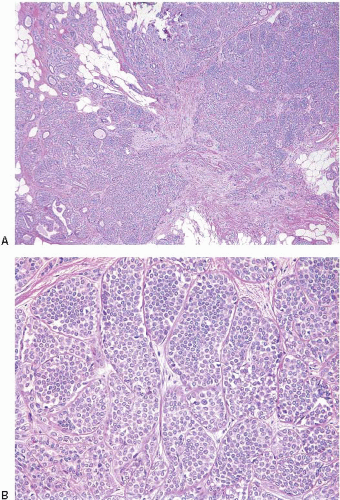

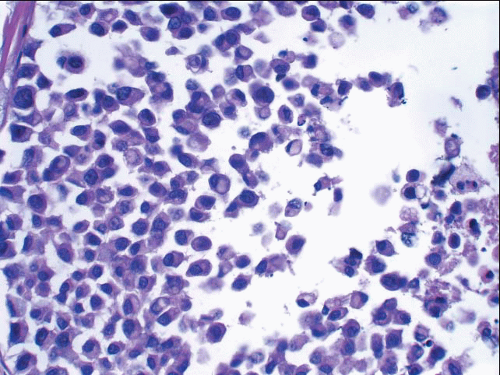

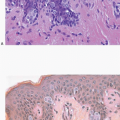

In some cases, the nuclear, cytoplasmic, and/or architectural features deviate from the classical appearances of LCIS described previously. Pleomorphic LCIS is characterized by nuclear pleomorphism with at least a two- to threefold variation in nuclear size, nuclear membrane irregularity, and variably prominent nucleoli (Fig. 5.9, e-Fig. 5.6).3,7,9,10,12, 13 and 14 In some cases of pleomorphic LCIS, the cells have apocrine features with abundant, eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 5.10, e-Fig. 5.7). Mitoses may be

observed and may be numerous. Foci of central, comedo-type necrosis may be present in the involved spaces, and this necrotic debris may undergo calcification (Fig. 5.11). The combination of nuclear pleomorphism, mitoses, and central necrosis often raises the possibility of high-grade DCIS (see the Differential Diagnosis section). As for classical LCIS, the cells of pleomorphic LCIS typically show loss of cell membrane expression of E-cadherin.7,13,14

observed and may be numerous. Foci of central, comedo-type necrosis may be present in the involved spaces, and this necrotic debris may undergo calcification (Fig. 5.11). The combination of nuclear pleomorphism, mitoses, and central necrosis often raises the possibility of high-grade DCIS (see the Differential Diagnosis section). As for classical LCIS, the cells of pleomorphic LCIS typically show loss of cell membrane expression of E-cadherin.7,13,14

FIGURE 5.9 Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ. The cells show variation in nuclear size and shape and irregularity of the nuclear membranes. |

FIGURE 5.10 Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ. In this case, the cells have apocrine features, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. |

Cytoplasmic alterations that may be seen in LCIS include clear cell change (Fig. 5.12) and apocrine change,15 which may be seen in both pleomorphic LCIS as mentioned previously and in otherwise classical types of

LCIS (Fig. 5.13, e-Fig. 5.8). In some cases, the cells have a myoid appearance, with dark, eccentric nuclei and cytoplasmic eosinophilia similar to features that characterize rhabdomyoblasts (Fig. 5.14).

LCIS (Fig. 5.13, e-Fig. 5.8). In some cases, the cells have a myoid appearance, with dark, eccentric nuclei and cytoplasmic eosinophilia similar to features that characterize rhabdomyoblasts (Fig. 5.14).

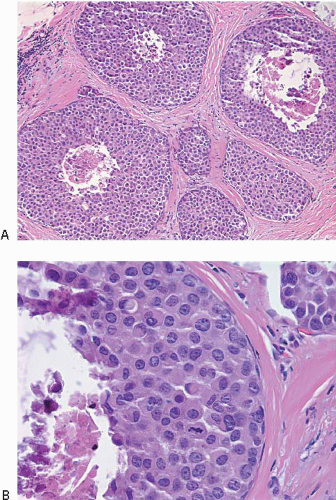

Variant architectural alterations may be seen. Some cases exhibit a mosaic growth pattern in which the cells are cohesive and have distinct cell borders (rather than the usual loosely cohesive pattern) (Fig. 5.15). In other cases, the lesion is composed of cells with the cytologic features of classical LCIS (either type A or type B cells), but the acini are markedly distended and foci of comedo necrosis may be present (Fig. 5.16, e-Fig. 5.9).9,10,14,16 These lesions have sometimes been referred to as “florid LCIS.” The involvement of collagenous spherulosis by LCIS produces a pseudocribriform pattern that mimics cribriform pattern DCIS.14,17

FIGURE 5.15 Lobular carcinoma in situ with cohesive, mosaic pattern of cell growth. Distinct cell borders are evident. |

Immunophenotype and Genetics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree