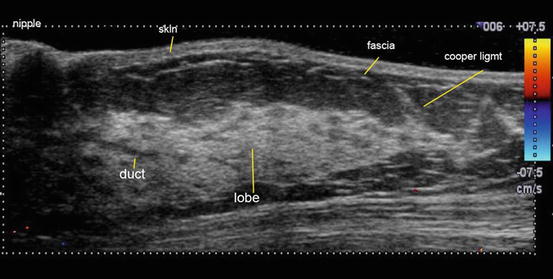

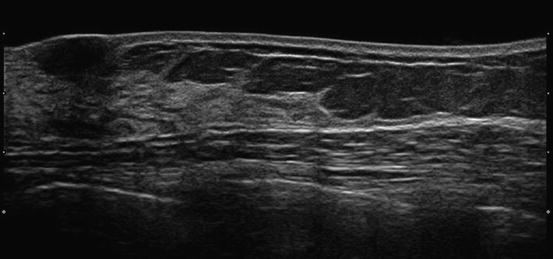

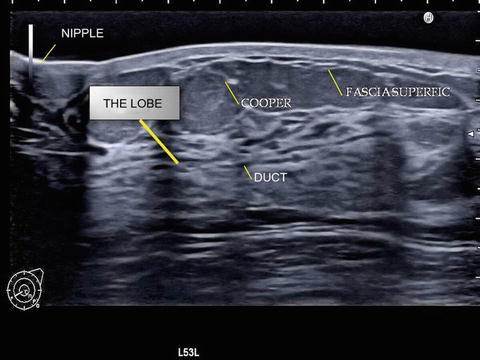

Fig. 4.1

Young woman thick lobe with lobular and ductal hyperplasia and poor fatty tissue

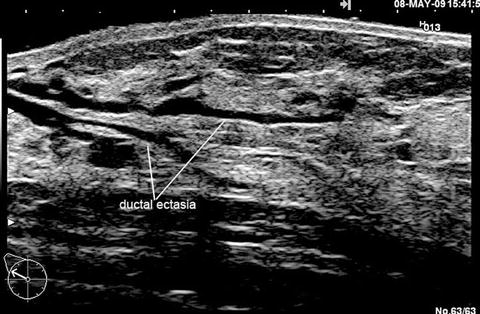

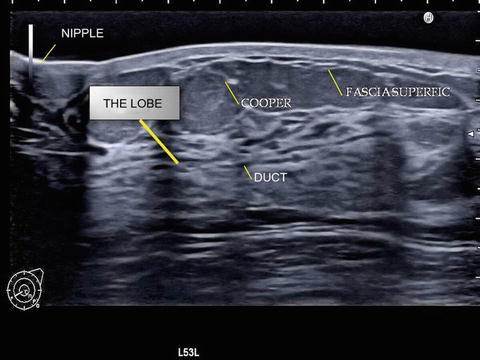

Fig. 4.2

Ultrasonic scan of an adult breast: ductal ectasia in the main ducts

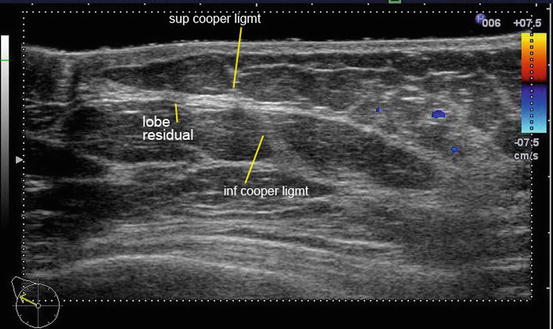

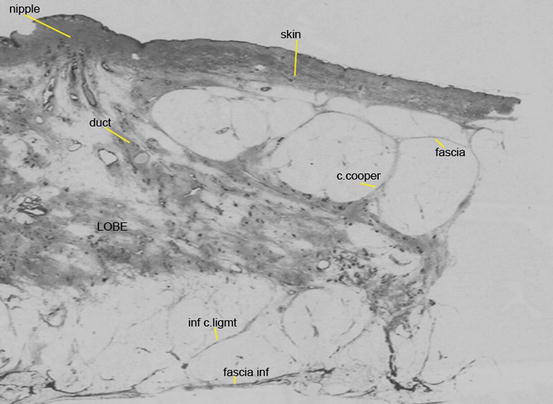

Fig. 4.3

Premenopausal lobar reduction and fatty thickening

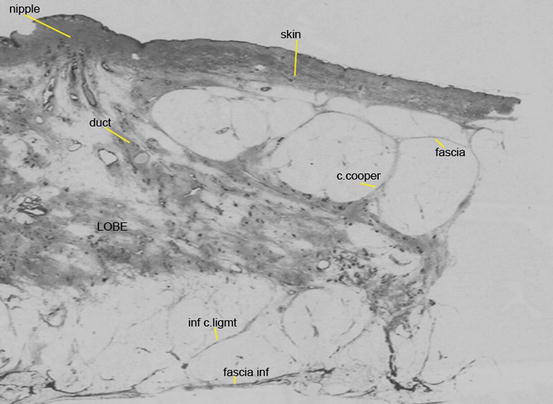

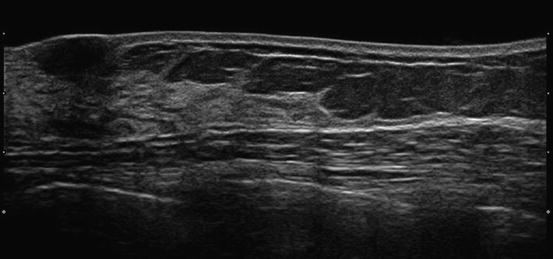

Fig. 4.4

Postmenopausal important lobar involution

The Concept of Breast Study

Breast pathology is a pathology of the epithelial cells. Mammary epithelium is located along the acino-ductal axis and is found in every lobe. The lobe of the breast is, in part, composed of fibrous and fatty tissue. The functional breast is limited by the external skin and lies on the internal pectoral muscle.

The primary goal of DE is the investigation of the ductal axis and its lobules, as well as a study of the entire lobe and ligamentous structures and any pathological modifications (both within and external to the lobe itself).

It is essential to distinguish conventional breast echography from that of ductal echography.

Conventional echography utilizes systematic orthogonal scanning of all breast quadrants with a high frequency probe of limited length. This technique is used by 90 % of the radiologists.

Ductal echography in contradistinction employs radial technique with concentric scanning circumferentially performed around the nipple examining each individual lobe by locating first each lobal duct at the N/A junction and following it to its terminos. If done properly, the tail of spence, if present, will be investigated fully. The technique is best performed with a lung transducer and use of a water bag mat will prevent pressure induced obfuscation of potentially diagnostic clues. The examination is carried out on the supine patient and does not take longer than 10 min for the investigation of a lesion-free breast by an experienced sonographer.

This technique allows the anatomical study of the breast and correlates remarkably with the large anatomico-pathological sections achieved by Professor Tibor Tot (Figs. 4.5, 4.6, and 4.7).

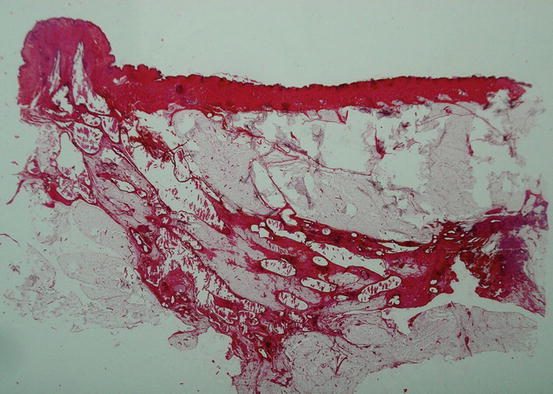

Fig. 4.5

Large anatomopathological breast section: all the anatomic elements are perfectly identified (courtesy of Pr T. Tot Sweden)

Fig. 4.6

Perfect correlation of the ducto-lobar echography: evidence of the exact similitude with the anatomical description

Fig. 4.7

Another ducto-lobar echography

Examination of these sections allows the investigation to see with precision:

The nipple with its internal ductal structures, the areola and the skin.

Under the skin, a thin layer of fat limited by the fascia superficialis.

The fascia linked to the skin by fine conjunctival structures: the retinacula cutis.

Below the fascia the presence of fatty tissue towering above the elongated shape of the mammary lobe.

The upper surface of the lobe bristling with Cooper’s ligaments connecting the lobe to the fascia superficialis.

The distal part of the lobe ending with ligaments (those connecting the lobes to the sub-clavicular area are called Giraldes ligaments).

The lower portion of the lobe giving a reversed mirror image of the upper portion with shorter lower ligaments connecting it to the lower fascia.

The fascia wending its way along the pectoral muscle.

Relationship Between Anatomy and the Development of Breast Cancers

In the early detection of breast cancers, the initial modifications of Cooper’s ligaments and the fasciae correspond to the first extra-lobar signs of the development of cancer, as described by Gallager and Martin in their 1969 publications [3] and by Nakama in his 1991 publications [4].

In their first article “early phases in the development of breast cancer,” Gallager describes the involvement of the conjunctival tissue in the initial carcinogenic process.

J de Brux in his 1979 book “Histopathology of the Breast” underlines this as well. Lastly, in several publications, Nakama describes the “invasive process of the breast and fixation to the skin.” He shows that cancerous cells together with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and fibroblasts migrate along Cooper’s ligaments towards the fascia superficialis and the skin.

Therefore it is obvious that it is essential to identify the ligaments and the fasciae to discover early modifications.

On a radial lobar section, T. Tot shows the localization of a small breast cancer at the junction of a Cooper’s ligament with the ductal axis (Fig. 4.8).

Fig. 4.8

very large lobar anatomopathological section with a small cancer located at the crossing section of a ductal axis and a cooper ligament axis (TDULs) (courtesy of Pr T. Tot)

All the investigations cited confirm localization of lesions (both benign and malignant) in Cooper’s ligaments. The Termino-Ducto-Lobular Unit is the nidus where lesions will develop and are to be found at the base of the ligaments.

To be able to identify the millimetric anatomical elements involved in the millimetric pathology of the breast is enormously helpful in the early diagnosis of breast cancer. Therefore one must search for these initial modifications in these very elements.

The remarkable correlation between ultrasound and anatomopathology is visualized in the example displayed below. The discovery of the primary cancer combined with multifocal and multicentric lesions made mastectomy necessary (Figs. 4.9, 4.10, and 4.11): ducto-radial ultrasound, a one centimeter thick image of a large section of the breast and an anatomopathological study on an 8 cm long glass plate.