Prepregnancy BMI (WHO classification)

Recommended gestational weight gain (kg)

Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2)

12.5–18

Normal weight (BMI 18.5–25 kg/m2)

11.5–16

Overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2)

7–11.5

Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)

5–9

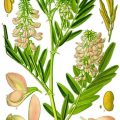

Fig. 12.1

WHO statistics on obesity worldwide stratified for income

There is evidence that obesity may be a risk factor for PTB, but the details of this relationship are not completely understood and often inconsistent [6, 10–12]. Results from new large population-based studies from Sweden [13] and California [14] take into account a more complex interaction. In a review including results from both the Swedish and Californian studies, all together including almost 3.5 million deliveries, the phenotype of PTB is considered [5]. In the analysis the authors have in details looked at both spontaneous and medically induced deliveries, the impact of gestational age by dividing deliveries into extreme preterm (22–27 weeks), very preterm (28–31 weeks), and moderately preterm deliveries (32–36 weeks) as well as the dose-response relationship with increasing BMI and across ethnic backgrounds. They find that increasing levels of obesity leads to preterm delivery via two mechanisms: first of all by increasing the PTB-associated comorbidities of gestational diabetes (GDM) and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Preterm births secondary to these comorbidities occur in both spontaneous and medically induced deliveries and across all gestational ages. When removing women with the comorbidities, a second relationship reveals that appears to be due to obesity per se (Table 12.2). This relationship is mostly in the very preterm deliveries. Based on these studies, it is suggested that initiatives and intervention to reduce obesity are important strategies to reduce both spontaneous and medically induced PTB. Considering the high morbidity and mortality associated with extreme preterm-delivered infants, even small differences in risk may have consequences for future outcomes.

BMIa | 22–27 weeksb | 28–31 weeks | 32–36 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

n (%) | OR (95 % CI) | n (%) | OR (95 % CI) | n (%) | OR (95 % CI) | |

Normal (18.5 to <25) | ||||||

California | 785 (0.15) | 1 (ref) | 1,164 (0.23) | 1 (ref) | 12 954 (2.56) | 1 (ref) |

Swedenc | 679 (0.07) | 1 (ref) | 1,151 (0.12) | 1 (ref) | 19 855 (2.03) | 1 (ref) |

Overweight (25 to <30) | ||||||

California | 481 (0.18) | 1.13 (1.01, 1.27) | 553 (0.21) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) | 6,166 (2.29) | 0.85 (0.82, 0.87) |

Sweden | 319 (0.09) | 1.20 (1.04, 1.38) | 394 (0.11) | 0.91 (0.81, 1.03) | 6,813 (1.88) | 0.92 (0.89, 0.94) |

Obesity I (30 to <35) | ||||||

California | 305 (0.25) | 1.58 (1.38, 1.80) | 253 (0.21) | 0.84 (0.73, 0.96) | 2,787 (2.27) | 0.82 (0.79, 0.86) |

Sweden | 100 (0.10) | 1.25 (1.01, 1.56) | 142 (0.14) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.29) | 1,902 (1.85) | 0.86 (0.82, 0.90) |

Obesity II (35 to <40) | ||||||

California | 128 (0.28) | 1.79 (1.48,2.16) | 103 (0.23) | 0.92 (0.75, 1.13) | 979 (2.17) | 0.78 (0.73, 0.84) |

Sweden | 39 (0.14) | 1.62 (1.15, 2.26) | 42 (0.15) | 1.09 (0.79, 1.50) | 548 (1.96) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.94) |

Obesity III (40 +) | ||||||

California | 84 (0.36) | 2.21 (1.76, 2.77) | 51 (032) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) | 515 (2.22) | 0.79 (0.72, 0.86) |

Sweden | 19 (0.21) | 2.38 (1.48, 3.81) | 11 (0.12) | 0.79 (0.42, 1.48) | 167 (1.88) | 0.80 (0.69, 0.94) |

This chapter goes through a number of lifestyle intervention studies in obese pregnant women and the considerations about the difficulties in reducing clinical complications. Furthermore, the need for future clinical trials with focus on different aspects of PTB as a complex phenomenon is discussed.

12.2 Lifestyle Intervention in Obese Pregnant Women

Pregnancy offers the opportunity to manage or prevent obesity as many women are concerned with the health of their babies during pregnancy and are in frequent contact with their healthcare professionals. Excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) is associated with increased risk of maternal and fetal complications as well as postpartum weight retention. A recent meta-analysis found that excessive weight, also in the normal weight women, influences offspring obesity over the short and long term (Fig. 12.2) [15].

Fig. 12.2

Pooled estimates of offspring obesity due to maternal excess weight gain during pregnancy by quality effect model [15]

A number of clinical trials about lifestyle intervention in overweight and obese women have been published. The majority of these studies have focused on lifestyle changes including dietary or physical activity or a combination of both attempts. Several of the studies have used GWG as the primary outcome and/or whether women gained below, within, or above the American Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations on GWG. The IOM recommendations were revised in 2009 suggesting overweight women to gain 7–11.5 kg and obese women to gain 5–9 kg during pregnancy (Table 12.3) [16]. Most studies have not been powered to look at the clinical maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Table 12.3

WHO’s BMI classification

BMI (kg/m2) | Classification |

|---|---|

< 18.5 | Underweight |

18.5–24.9 | Normal weight |

25–29.9 | Overweight |

≥ 30 | Obesity |

30–34.9 | Obesity class I |

35–39.9 | Obesity class II |

≥ 40 | Obesity class III |

12.2.1 The Australian LIMIT Study

The Australian LIMIT study is the so far the largest published randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 2,212 overweight or obese pregnant women included [17]. Women randomized to lifestyle intervention were provided with dietary advices and individual diet plans and were encouraged to exercise. The behavioral strategies were provided during a face-to-face visit after inclusion and in gestational week 28 with a research dietician and followed up by three personal phone calls in between. The study did not succeed in reducing infants born large for gestational age (LGA) which was the primary outcome. Furthermore, there was no significant reduction in GWG between groups. But they found a significant reduction in the risk of birth weight above 4.5 kg, a reduction in respiratory distress in the neonates, as well as a shorter length of postnatal hospitalization. They also found a 26 % reduction in PTB and a 53 % reduction in preterm primary rupture of the membranes (PPROM), although these differences did not reach statistical significance [18].

12.2.2 The Irish ROLO Study

In the ROLO study (Randomized Control trial of low glycemic index diet to prevent macrosomia in euglycemic women) in Ireland, 800 euglycemic pregnant women in all BMI categories were randomized to receive low glycemic index and healthy eating diary advice in a group session before 22 weeks of gestation or to a standard control group [19]. Based on a 3-day food diary during each trimester, the intervention group had a significantly lower energy intake and reduced intake of food with high glycemic index. The intervention group had significantly lower GWG (kg) compared to the control group mean 11.5 ± 4.2 vs. 12.6 ± 4.4 kg, p = 0.003 and a lower percentage of women in the intervention group exceeded the IOM recommendations on GWG. No difference in birth weight or neonatal abdominal circumference was seen. A lower neonatal waist circumference/length ratio was reported in the intervention, suggesting that a low glycemic index food intake limited central adiposity [20].

12.2.3 The Danish LiP Study

Among one of the most comprehensive randomized controlled trials on obese pregnant women is the Danish LiP (Lifestyle in Pregnancy) study [21]. In total, 360 obese pregnant women were included and randomized to intervention or control before 14 weeks of gestational age. Women randomized to intervention group received four individual diet counseling sessions during pregnancy and an exercise program consisting of aerobic classes (1 h weekly), free fitness membership during pregnancy, and exercise-motivating initiatives. The intervention group had significantly lower GWG (kg) compared to the control group (median [IQ-range]): 7.0 [4.7–10.6] vs. 8.6 [5.7–11.5]) (p = 0.01). No significant differences in the clinical outcomes with respect to preeclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, cesarean section, large for gestational age (LGA) infants, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit were found. The study measured a number of metabolic outcomes throughout pregnancy and found that lifestyle intervention resulted in attenuation of the physiologic pregnancy-induced insulin resistance [22]. The intervention had no effect on duration of breastfeeding or postpartum weight retention [23]. The study is the first pregnancy intervention trial to publish detailed follow-up in the offspring, showing no anthropometric or metabolic effects at 2.5–3 years of age [24, 25].

12.2.4 The Danish TOP study

The TOP study (Treating Obesity in Pregnancy) is another Danish RCT with 425 obese pregnant women randomized into three intervention arms with physical activity (pedometer), physical activity and dietary counseling (dietician every second week), or control group [26]. Renault et al. found that physical activity intervention assessed by pedometer with or without dietary intervention reduced the GWG significantly compared to controls. They found no differences in any of the obstetric or neonatal outcomes. The study reported only a few cases of very preterm and preterm deliveries without any difference between groups.

12.2.5 Single-Center Interventional Studies

A number of other studies have focused on GWG and found different results. Wolff et al. [27], Claesson et al. [28], and Thornton et al. [29] reported significantly lower GWG in the intervention groups of obese women compared to controls, whereas Jeffries showed that overweight – but not obese women – gained significantly less weight after lifestyle intervention [30]. Quinlivan et al. [31] and Asbee et al. [32] succeeded in limiting GWG in women in the intervention group with mixed BMI categories. The “Fit for Delivery Study” by Phelan et al., a low-intensity behavioral RCT with 410 normal and overweight to obese women in the USA, found that the intervention significantly decreased the percentage of normal weight women who exceeded the 1990 Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations on GWG, but did not significantly affect GWG in overweight and obese women [33]. Olson’s group reported significantly lower GWG in a subgroup of low-income women only [34]. Regarding obstetric outcomes, Quinlivan et al. found a significant reduction in GDM in the intervention group [31], Asbee reported a significant reduction in emergency cesarean delivery in the intervention group [32], and Luoto found a significant reduction in birth weight [35]. In a Belgian RCT from Guelinckx et al., a less intensive lifestyle education from nutritionists did not significantly affect GWG [6]. However, a later Belgian RCT found a significant reduction in GWG in the intervention group receiving antenatal lifestyle intervention focusing on mental and physical health [36].

Randomized controlled trials focusing on physical exercise only have evaluated on the effect of exercise intervention on GWG [37–40]. In these trials the group of exercising women had less GWG compared to control groups. However, these GWG differences were insignificant probably due to small sample sizes. A large Norwegian RCT with 855 healthy women reported results from a 12-week exercise program performed during the second trimester [41]. The primary aim of the study was to prevent GDM, but no effect was seen between intervention and control groups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree