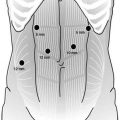

Fig. 10.1

Port placement for a laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy

To start, the left lobe of the liver is retracted and the lesser omentum is incised and entered. The fascia covering the right crus of the diaphragm is incised sharply and an attempt is made to create a retrogastric tunnel exiting to the left and superior to the gastric cardia. Generally, the connective alveolar tissue in this area is loose and permits passage of a blunt grasper to the left of the gastroesophageal junction. The stomach is retracted inferiorly during this maneuver to enhance visualization. Occasionally, especially with bulky tumors of the GE junction, posterior visualization is not optimal and we prefer to complete the mobilization of the upper half of the greater curvature of the stomach prior to completing the retrogastric tunnel. When we are able to visualize the grasper as it exits the left side of the GE junction, above the left crus, we pass a ½-inch Penrose around the GE junction and secure it with an endo-loop.

Mobilization of the upper greater curvature is done by the surgeon on the right side of the patient. The stomach is retracted superiorly and to the right. The assistant surgeon provides countertraction of the omentum, and the lesser sac is entered at a point generally halfway up the greater curvature of the stomach. We utilize the Articulating Tissue Sealer (ENSEAL® G2, Ethicon, USA) to divide the gastrocolic omentum in a standard fashion. Care is taken to preserve the right gastroepiploic vessels. Dissection is carried out toward the gastrosplenic ligament, and the short gastric vessels are divided. The fundus is further released by dissection from the superior splenic pole and division of the pancreaticogastric attachments and the posterior vagus nerve. Dissection progresses until the left crus is identified. The fascia over it is incised sharply, and the posteroinferior mediastinum is entered. If successfully completed initially, the surgeon should be able to visualize the Penrose drain previously placed around the GE junction. If not previously placed, the Penrose can be secured at this time.

We now proceed to mobilize the lower half of the greater curvature of the stomach in a similar fashion. This is performed from the left side of the table. All adhesions of the gastric posterior wall to the pancreas are dissected until full mobilization of the stomach is achieved. A Kocher maneuver is performed to ensure optimal gastric mobilization to the thorax. Adhesions of the duodenum to the liver, gallbladder, or porta hepatis are divided.

Attention is now directed toward isolating the left gastric artery and vein. The stomach is retracted superiorly, and surrounding lymph nodes and fatty tissues are dissected to adequately visualize the celiac axis and origin of the common hepatic artery and splenic artery. Retropancreatic lymph nodes along the proximal splenic artery may be included in the dissection. Lymphatic and fatty tissue is cleared up to the crus which should have been previously dissected, guaranteeing the stomach is completely free except for the left gastric vessels. The left gastric artery and vein are divided and ligated with the ECHELON FLEX™ Powered ENDOPATH® Stapler (Ethicon, USA) utilizing a vascular load (1.5 mm staples).

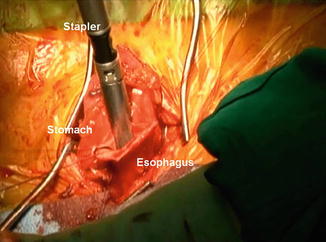

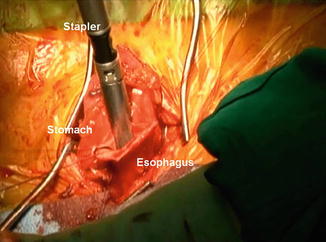

The gastric conduit is created with a series of firings of the 6 cm ECHELON FLEX™ Powered ENDOPATH® Stapler (Ethicon, USA) along the lesser curvature of the stomach. Care is taken to pull the nasogastric tube back into the GE junction prior to stapler application. The stapler is applied from the right 12 mm port. Stapling is completed except for the final centimeter, leaving the esophagus attached to the conduit so it can be used to transfer the stomach into the posterior mediastinum.

Attention is returned to the hiatus where the distal esophagus is further mobilized circumferentially while utilizing retraction on the Penrose previously placed. Included in this step should be wide division of the phrenoesophageal ligament. After this, the posterior mediastinum can be entered to continue dissection with mediastinal lymph node dissection up to the level of the carina.

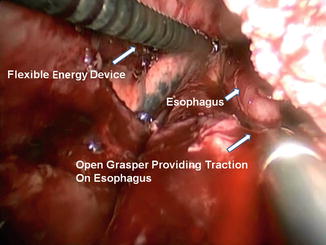

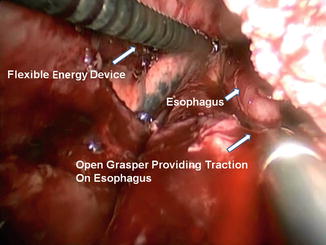

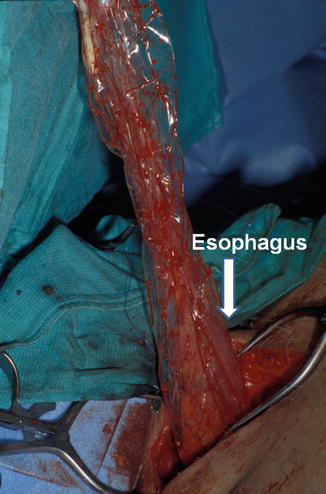

At this level, superior dissection continues close to the esophagus with mobilization of the proximal esophagus away from the trachea and prevertebral fascia. Traction of the Penrose located at the GE junction inferiorly and laterally aides with the dissection. The use of an open grasper on the esophagus (Fig. 10.2) to generate posterior or anterior traction close to the area of dissection is also useful. Generally, dissection can be carried up to the thoracic inlet and distal cervical esophagus.

Fig. 10.2

The use of open grasper on esophagus to facilitate mediastinal dissection

Cervical Component

A left cervical incision is performed along the anterior sternocleidomastoid muscle. We routinely incise the strap muscles transversely and expose the middle thyroid vein which is commonly divided and ligated with sutures. The jugular vein and carotid artery are retracted laterally as the thyroid is retracted superiorly and laterally. This exposes the cervical esophagus. Care is taken to identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The esophagus is circumferentially dissected and a Penrose is secured around it. Using mild traction of the proximal cervical esophagus, blunt dissection is used to free the cervical esophagus to the thoracic inlet. The degree of dissection will depend on the degree of success of our mediastinal dissection. Once the esophagus is completely free from adjacent tissues, the esophagus and gastric tube can be pulled through the cervicotomy. The nasogastric tube is pulled into the cervical esophagus, and after completing transection of the stomach, an end-to-end esophagogastric anastomosis is performed. Care is taken to bring the gastric tube oriented correctly, with the staple line toward the right mediastinum. Laparoscopic visualization as well as assistance with the transfer is performed through the abdominal ports.

For bulky tumors that may not be able to be successfully pulled through the mediastinum, we vary the technique by amputating the proximal esophagus and pulling the esophagus into the abdomen. A small upper midline incision is made, and the specimen is then removed abdominally after completing transection of the stomach. The gastric conduit is brought up to the posterior mediastinum by using a large Foley attached to the end of a thin laparoscopy bag that drapes over the conduit. The Foley is introduced into the neck and brought out the hiatus. By applying suction and traction to the Foley, the plastic adheres to the viscera and allows for gentle traction and correct orientation of the gastric tube as it is brought out the neck (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.3

Gastric tube is placed in a plastic laparoscopy bag attached to a Foley previously passed from the neck through the mediastinum. Suction on the Foley collapses the plastic on the viscera and allows for gentle traction into the neck

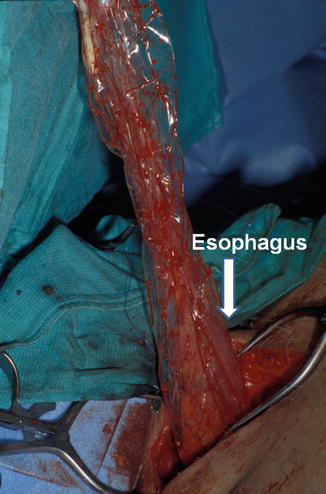

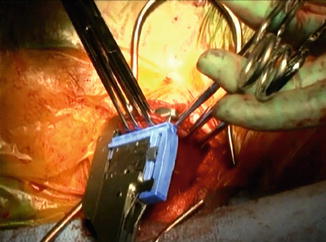

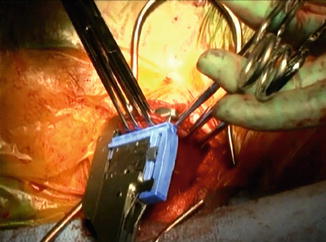

For the esophagogastric anastomosis, we prefer a modification of the technique described by Collard et al. [21], utilizing a side-to-side anastomosis. The back wall is created with an application of the 6 mm ECHELON FLEX™ Powered ENDOPATH® Stapler (Ethicon, USA) (2.5 mm) (Fig. 10.4). The anterior layer is closed utilizing a triangulation technique with a PROXIMATE® Reloadable Staplers (TX) 30 mm (Ethicon, USA) (Fig. 10.5). The nasogastric tube is advanced to just proximal to the pylorus. A pyloromyotomy is not performed. A 19-round Jackson-Pratt drain is placed in each pleural cavity and brought out through the hiatus into the abdomen and out of the abdominal port sites. A jejunal feeding tube is placed, and all incisions are closed.

Fig. 10.4

Side-to-side anastomosis from the cervical esophagus to the gastric tube, utilizing a 6 cm stapler

Fig. 10.5

Closure of anterior wall of anastomosis with a triangulation technique

Outcomes

Complications and outcomes are significantly influenced by the volume of patients, because a large learning curve exists. High-volume centers tend to have more experience and, therefore, better outcomes than smaller-volume hospitals [22, 23]. Minimally invasive techniques for esophageal resection have been reported to have acceptably reduced procedure-related morbidity without compromising disease-free survival rates. Luketich et al. have the largest reported experience to date. Their initial series of 222 patients has now grown to more than 1,000 patients. In this series, mortality was 1.4 % versus 5.5 % for an open approach [5]. Furthermore, the survival curve at 19 months of follow-up was comparable in both groups. In another analysis of 41 elderly patients over the age of 75 years who underwent minimally invasive esophagectomy, no operative deaths occurred, with a survival of 81 % at 20 months of follow-up [24]. A recent meta-analysis of the available literature suggests that patients undergoing MIE had better operative and postoperative outcomes with no compromise in oncologic outcomes (as assessed by lymph node retrieval) [14]. Patients receiving MIE had significantly lower blood loss and shorter postoperative ICU and hospital stay. There was a 50 % decrease in total morbidity in the MIE group. Subgroup analysis of comorbidities demonstrated significantly lower incidence of respiratory complications after MIE; however, other postoperative outcomes such as anastomotic leak, anastomotic stricture, gastric conduit ischemia, chyle leak, vocal cord palsy, and 30-day mortality were comparable between the two techniques.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree