Figure 12.1

Patient positioning for a laparoscopic right adrenalectomy

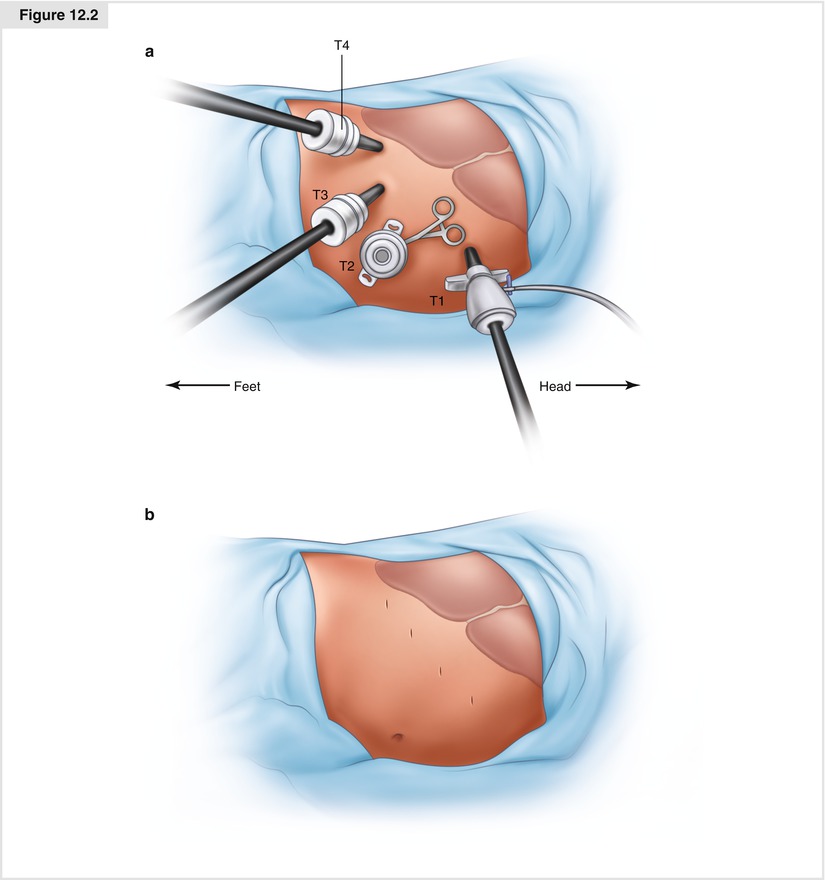

Figure 12.2

(a) Trocar sites for laparoscopic right adrenalectomy. (b) Placement of trocar sites to facilitate dissection of a large tumor

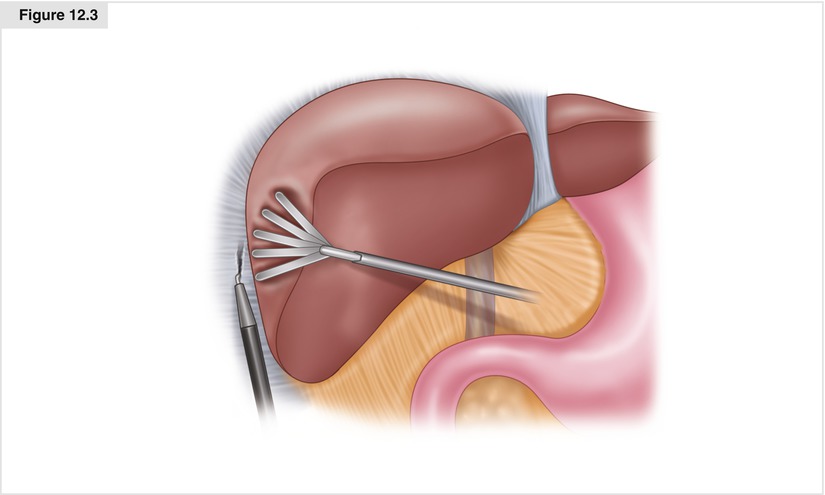

Figure 12.3

Dissecting the triangular ligament to mobilize the right liver

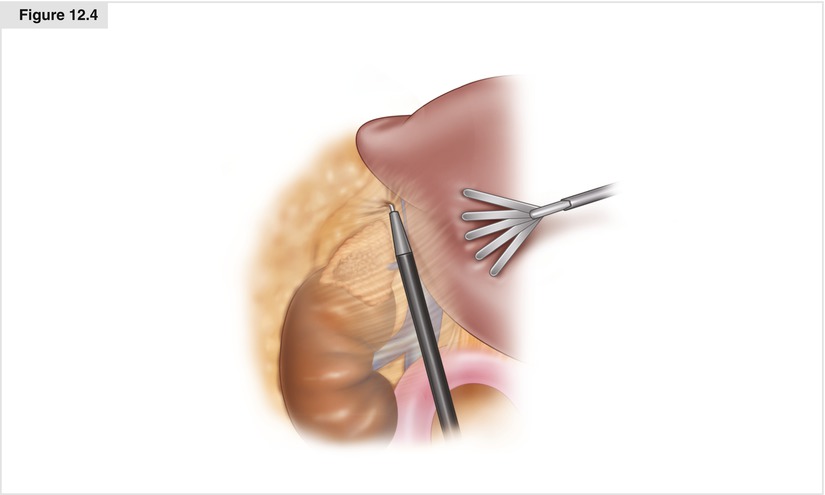

Figure 12.4

The apex of the adrenal gland’s two limbs is dissected free, and the surgeon uses hook cautery to continue the dissection inferiorly

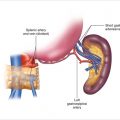

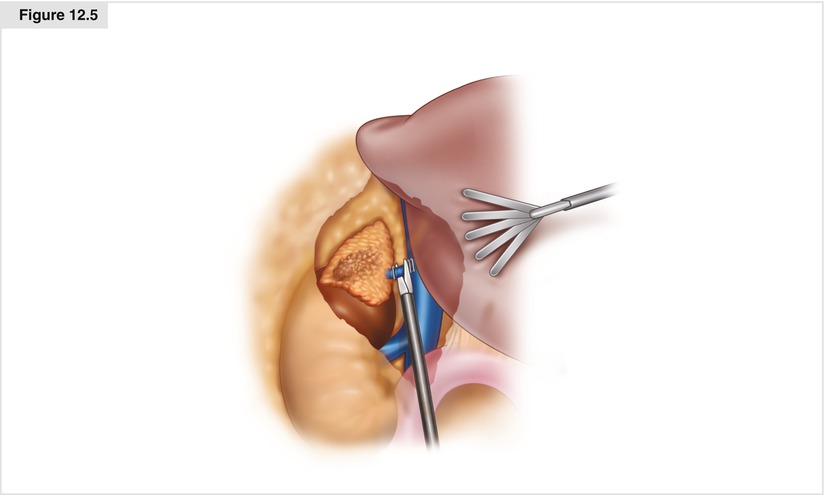

Figure 12.5

Identification, dissection, and ligation of the adrenal vein

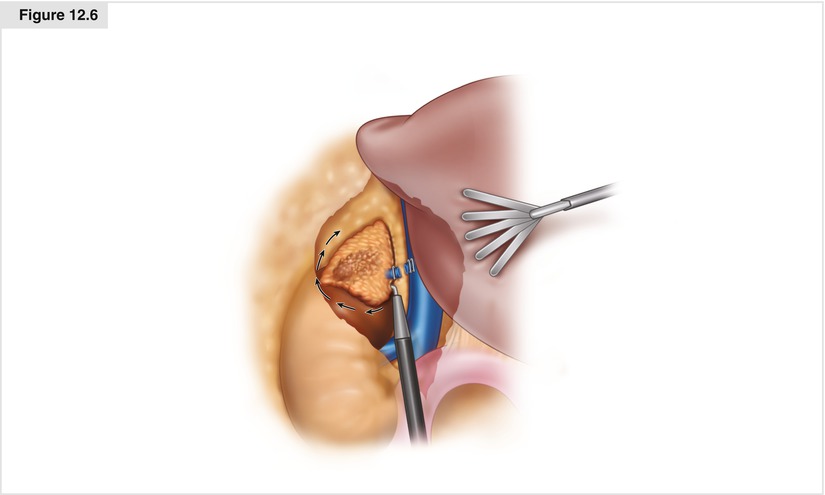

Figure 12.6

Dissection of the inferior edge of the adrenal gland away from the renal vein and hilum

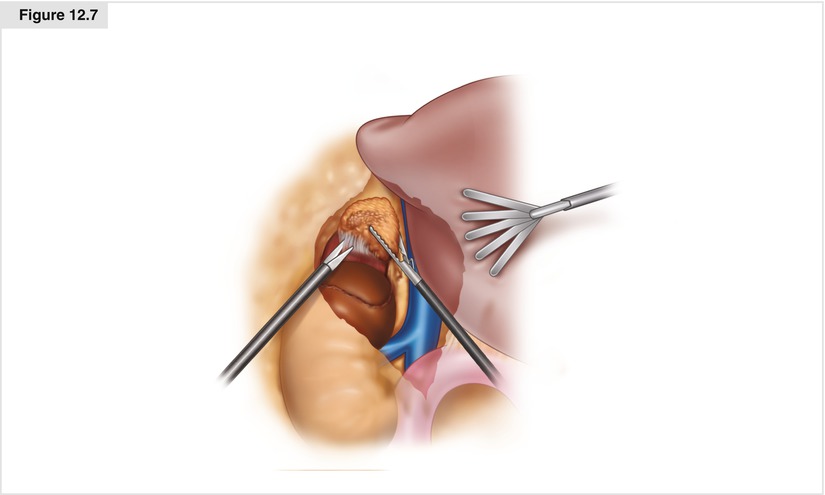

Figure 12.7

Separation of the periadrenal fat from the posterior muscle attachments

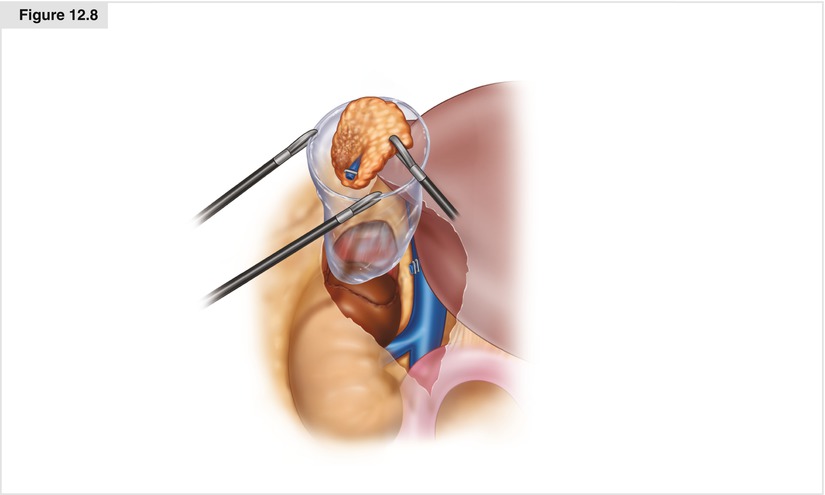

Figure 12.8

Removal of the specimen

12.2.2 Laparoscopic Left Adrenalectomy

Similar to a laparoscopic right adrenalectomy, for a laparoscopic left adrenalectomy the patient is placed in a modified right lateral decubitus position (80° angle) with the aid of a beanbag (Fig. 12.9a). The patient is leaned slightly back to allow for better exposure to the anterior abdomen. An axillary roll is placed, and the bed is flexed to open the space between the costal margin and the iliac crest. Pillows are placed between the patient’s legs, which are slightly bent to maintain a neutral position, and the patient is secured to the bed with 3-inch cloth tape across the knees, hips, and chest. The patient’s left arm is laid on pillows or an arm board, and the patient’s right arm is flexed at the elbow.

Pneumoperitoneum is established using a Veress needle approximately 1–2 cm below the left subcostal margin in the midclavicular line (Palmer’s point). The intra-abdominal pressure is initially bought to 20 mmHg and a 10-mm dilating trocar is placed (T1). Close communication with the anesthesiology team is paramount to look for a decrease in end-tidal CO2, possibly indicating a CO2 embolism. The pneumoperitoneum is then decreased to 15 mm Hg, and three additional 10-mm trocars are placed 1–2 cm below the left subcostal margin, evenly spaced between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line (T2–T4; Fig. 12.9b).

The first step in the operation is to release the splenic flexure of the colon (Fig. 12.10). This is done using hook cautery. The avascular attachments of the colon are demonstrated by retracting the colon inferiorly with an atraumatic laparoscopic grasper. Additional dissection may be necessary along the superior portion of the white line of Toldt to drop the colon away from the spleen.

A medial visceral rotation is then performed by dissecting the lateral attachments of the spleen off the lateral abdominal wall (Fig. 12.11). The dissection plane is between Gerota’s fascia and the spleen and tail of the pancreas. A fan retractor can be used to gently retract the spleen and pancreas, allowing the surgeon to dissect the avascular attachments to the abdominal side wall and Gerota’s fascia. This is a key step in the operation, and the surgeon must be mindful to stay in the plane anterior to Gerota’s fascia instead of in the fascia or behind the kidney. As the spleen is rotated medially, the surgeon can identify the tail of the pancreas by its subtle yellow color, which is distinct from the surrounding retroperitoneal fat and the splenic vein running along its posterior edge. The dissection stops when the surgeon sees the fundus of the stomach at the cephalad limit of the dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree