Author

Year

Lap

Open

Adequacy of resection

Results for lap group

Survival

Kitano et al. [11]

2002

14a

14

Identical

Less EBL and pain, earlier recovery of bowel function

na

Hayashi et al. [16]

2005

14a

14

Equally radical

Shorter epidural use

na

Lee et al. [17]

2005

24a

23

No significant difference

Fewer pulmonary complications

No difference at 14 months

Huscher et al. [12]

2005

30

29

No significant difference

No difference

No difference at 5 years

Kim et al. [15]

2008

82a

82

na

Less EBL and pain medicine, shorter hospital stay, improved QOL

na

Kim et al. [14]

2010

179a

161

na

No difference in morbidity or mortality

na

Cai et al. [18]

2011

61a

62

No difference

Less pulmonary infection

No difference at 2 years

Several meta-analyses of randomized and nonrandomized trials have been published. A recent meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy concluded that laparoscopic gastrectomy was associated with lower blood loss, faster return of bowel function, and a shorter hospital stay but a slight reduction in lymph node yield [19]. Although there was no difference in the proportion of patients with 15 or more lymph nodes in their specimen, the laparoscopic group had a median of 3.9 fewer lymph nodes than the open group. The implications of this small difference in lymph node yield is unclear [19]. A meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for early stage gastric cancer concluded that the laparoscopic approach was associated with longer operative times, less blood loss, earlier return of bowel activity, and shorter hospital. They also found that laparoscopic resection yielded slightly fewer lymph nodes [20]. Two meta-analyses focusing on patients with locally advanced gastric cancer had similar conclusions except that the lymph node yields of the laparoscopic groups in these meta-analyses were similar to the open groups [21, 22].

In most of the Asian studies, the laparoscopic groups included a large proportion of patients undergoing open intestinal transection and gastrojejunal or gastroduodenal anastomoses. In Western series, the procedures almost always include intracorporeal anastomoses and are therefore considered laparoscopic as opposed to laparoscopic-assisted resections. Compared to laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy, totally laparoscopic gastrectomy is associated with less blood loss, shorter time to first flatus, and shorter postoperative hospital stay [23]. There is no significant difference in operative time, mean number of lymph nodes retrieved, and postoperative complications [23]. An evaluation of the largely nonrandomized Western data is therefore warranted (Table 22.2). Western series support the conclusions that, compared to open distal gastrectomy, laparoscopic distal gastrectomy takes longer [24–27] but yields a similar lymph node count [12, 26, 28–30] with less blood loss [12, 24, 26, 29], shorter hospital stay [12, 26–30], and lower postoperative morbidity [25–28]. Short-term [25, 27, 29, 30] and 5-year [12] survivals of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy are similar to those following open gastrectomy.

Table 22.2

Summary of Western distal gastrectomy studies

Author | Year | Country | Laparoscopic group (n) | Open group (n) | Laparoscopic lymph node harvest – mean | Open lymph node harvest – mean | Laparoscopic length of stay | Open LOS (days) | Laparoscopic 30-day morbidity | Open 30-day morbidity | Laparoscopic 30-day mortality | Open 30-day mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reyes et al. [24] | 2001 | USA | 18 | 18 | 8 | 11 | 6.3 | 8.6 | na | na | ||

Huscher et al. [12] | 2005 | Italy | 30 | 29 | 30 | 33 | 10.3 | 14.5 | 23.3 | 27.6 | 3.3 | 6.7 |

Dulucq et al. [28] | 2005 | France | 14 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 25 | 12.5 | 17.5 | 0 | 0 |

Pugliese et al. [29] | 2007 | Italy | 43 | 32 | 36 | 9.8 | 16.7 | 10 | 14 | 2 | 3 | |

Strong et al. [25] | 2009 | USA | 30 | 30 | 18 | 21 | 5 | 7 | 26 | 63 | 0 | 0 |

Guzman et al. [26] | 2009 | USA | 30 | 48 | 24 | 26 | 7 | 10 | 30 | 46 | 0 | 0 |

Scatizzi et al. [27] | 2011 | Italy | 30 | 30 | 31 | 37 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

Chouillard et al. [30] | 2010 | France | 51 | 79 | 19 | 22 | 8 | 11.5 | 12 | 16 | 0 | 2.5 |

Patient Selection

The decision to perform a laparoscopic versus an open gastrectomy depends on several factors. The most important consideration is the skill and experience of the operating surgeon. Laparoscopic gastrectomy is an operation requiring advanced laparoscopic skills to perform an adequate lymphadenectomy and an intestinal anastomosis. The procedure also requires an operating room team equipped with appropriate laparoscopic atraumatic graspers, an energy device, liver retractor, wound protector, and laparoscopic reticulating staplers. The procedure is particularly demanding in obese patients. Challenges in laparoscopic resection in obese patients include decreased surgical visibility, dissection hindered by adipose tissue, and difficulty with anastomoses. Higher BMI is an independent risk factor for pancreatic fistula following laparoscopic distal gastrectomy [31].

Prior upper abdominal surgery can make laparoscopic gastrectomy technically difficult. Laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy often results in adhesion of the first portion of the duodenum to the gallbladder bed. Careful dissection can usually allow full mobilization of the duodenum off the liver bed. An adequate lymphadenectomy can be performed following an open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy as long as the patient did not undergo an open common bile duct exploration. Prior right hemicolectomy or splenectomy can complicate laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Prior gastric resection or transverse colectomy is a relative contraindication to laparoscopic gastrectomy because the plane of dissection for lymphadenectomy will have been altered or obliterated. In general, adequate resection with lymphadenectomy can be accomplished following neoadjuvant chemotherapy but may be technically demanding in some patients who have had prior radiation therapy. As with any laparoscopic procedure, it is incumbent on the operating surgeon to be cognizant of their own surgical limitations and have a low threshold to convert any case to open if it cannot be performed thoroughly and safely laparoscopically. Poor cardiopulmonary reserve is a relative contraindication to laparoscopic gastrectomy because of the decrease in venous return and increase in pulmonary resistance associated with prolonged pneumoperitoneum.

Hand-assisted laparoscopic gastrectomy has been advocated by some surgeons in an attempt to overcome the technical challenges associated with a totally laparoscopic approach [32]. Although a hand assist approach may enable a surgeon early in their learning curve to complete a laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy, it will inevitably require an incision significantly larger than that required for specimen extraction with a totally laparoscopic approach. Routine reliance on the use of a hand port might also limit the surgeon’s own technical development and proficiency.

Patient Positioning and Room Setup

The patient is placed in the supine position with both arms tucked. General endotracheal anesthesia is administered. A nasogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach, and a Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder. Intravenous antibiotics are administered within 1 h of the incision and redosed as necessary. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis is accomplished with sequential pneumatic compression stockings on the lower extremities. In addition, all patients are administered 5,000 units of subcutaneous unfractionated heparin in the immediate preoperative period.

Eggcrate foam is secured to the operating room with wide tape, and the patient is placed on the eggcrate without an intervening bedsheet. This secures the patient to the surgical bed and prevents shifting during maximum reverse Trendelenburg position [33]. The video monitors are positioned near the shoulders on each side of the operating table. The procedure is performed with a surgeon and an assistant. The surgeon begins on the right side of the table with the assistant on the left side of the table. The scrub nurse is positioned on the right side of the table.

Operative Procedure (Video 22.1)

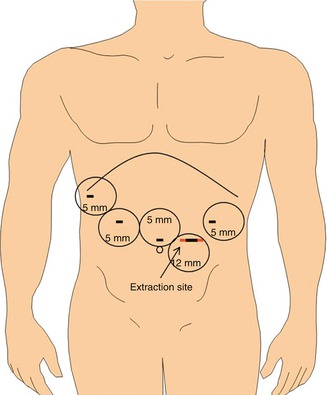

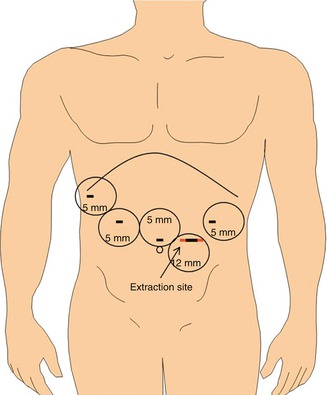

The procedure is performed with four 5 mm ports and a single 12 mm port for laparoscopic stapling (Fig. 22.1). The peritoneal cavity is entered and insufflated with a Veress needle after a stab wound is made in the left subcostal space at Palmer’s point. A 5 mm camera trocar is placed in the supra-umbilical region. A left upper quadrant 5 mm dissection port is placed. This port should be placed laterally enough to allow for placement of a 12 mm stapling port midway between the left upper quadrant and supra-umbilical ports. The abdomen is thoroughly explored for evidence of liver or peritoneal metastatic disease. If metastatic disease is identified, the operation can be aborted or converted to a gastrojejunal bypass, if clinically indicated. If distant metastatic disease is not identified, an extreme right lateral subcostal port is then placed. A snake retractor placed through the right lateral port is triangulated closed and used to elevate the left lobe of the liver. The snake retractor is fixed in place with an adjustable robot arm-type retractor system. A right upper quadrant 5 mm dissecting port is placed. A 5 mm 30° angled camera is used for the entire operation. With some equipment, the 5 mm camera does not allow enough light to accomplish advanced laparoscopy. If the operation cannot be performed safely with a 5 mm camera, the supra-umbilical 5 mm port can be exchanged for a 10–12 mm port for a 30° angled 10 mm camera.

Fig. 22.1

Laparoscopic port site placement. A 5 mm supra-umbilical camera port is flanked by the right and left upper quadrant 5 mm dissection ports. A 12 mm left-sided stapling port is later enlarged for specimen extraction. A 5 mm right lateral subcostal port site is used for placement of a liver retractor

The omentum is reflected into the upper abdomen and dissected off of the transverse colon using a 5 mm energy device (Table 22.3). Dissection is conducted from the right side of the table, beginning at the midline and extending up to the lowest short gastric vessels. For this dissection, the camera can be moved to the left 12 mm port to allow the surgeon to work with both hands through the right upper quadrant and supra-umbilical port. The omental dissection is then carried up to the greater curvature. The camera is moved from the left to the supra-umbilical port, and the right side of the omentum is dissected from the transverse colon. This is best performed from the left side of the patient. After the complete separation of the omentum from the transverse colon, the base of the right gastroepiploic vessels are dissected at the level of the inferior border of the pancreas. The right gastroepiploic vessels are transected using an energy device. Attention is then turned to the supra-duodenal region, and the lesser omentum is opened. The first portion of the duodenum is surrounded and transected using a 60 mm endoscopic stapler using 3.5 mm (blue) staples or Tri-StapleTM 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 mm (tan) staples. Staple line buttressing material is not used for any of the stapling in the procedure. None of the staple lines are imbricated with sutures, and sutures are not generally used to take tension off the staple lines.

Table 22.3

Sequence of laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy with gastrojejunostomy and D2 lymphadenectomy

1 | Omentectomy |

2 | Transection of right gastroepiploic vessels |

3 | Transection of postpyloric duodenum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|