There has been much speculation regarding differences in outcome for patients who have gastric cancer in the Eastern versus Western world. Among other factors, these differences have contributed to a unique cohort of patients and experience in the Western staging/evaluation of gastric cancer and in the application of minimally invasive approaches for treatment. This review summarizes the current state of laparoscopic approaches for the staging and treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma for patients presenting in Western countries, with their associated unique presentation, comorbidities, and outcomes.

Laparoscopic approaches for gastric carcinoma: Western experience

Gastric cancer represents an important worldwide health concern and is the second leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. Although the incidence is higher in Eastern countries (78 cases per 100,000 in Japan compared with 10 cases per 100,000 in the United States), it still remains the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, and each year, more than 21,000 Americans are diagnosed with gastric cancer and almost 11,000 die of the disease.

There has been much speculation regarding differences in outcome for patients who have gastric cancer in the Eastern versus Western world, especially considering the greater frequency of early gastric cancer in Eastern countries and their higher incidence of distal, intestinal-type tumors. This situation is in contrast to the Western experience of tumors that are more often identified at an advanced stage and are more often proximal in location or at the gastroesophageal junction and more often of diffuse-type histology. Among other factors, these differences have contributed to a unique cohort of patients and experience in the Western staging/evaluation of gastric cancer and in the application of minimally invasive approaches for treatment. This review summarizes the current state of laparoscopic approaches for the staging and treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma for patients presenting in Western countries, with their associated unique presentation, comorbidities, and outcomes.

Rational for Diagnostic Laparoscopy and Cytology

The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guidelines in Oncology emphasize the importance of managing gastric carcinoma via a multidisciplinary approach, including a team of dedicated oncologists specializing in gastroenterology, surgical oncology, medical oncology, pathology, and radiology for upper gastrointestinal cancers. Diagnosis requires upper endoscopy and biopsy for tissue diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) scanning and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) are important tests for staging. For patients who are found to have locally advanced disease, defined as T3 or greater or node-positive via EUS and CT evaluation, treatment recommendations include multimodality therapy. Before neoadjuvant treatment can begin, completion staging of these patients requires diagnostic laparoscopy to detect radiologically occult visible M1 disease, found in up to 40% of patients.

Diagnostic laparoscopy not only identifies visible, subradiographic M1 disease but also allows for collection of cytologic peritoneal washings for evaluation. Positive peritoneal cytology (positive for cancer cells) is now included in the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system as consistent with metastatic (M1) disease. This strategy is based on studies showing that despite complete (R0) resection of a gastric carcinoma, patients with positive peritoneal cytology have a median survival of months that parallels visible metastatic disease. There are almost no patients who have survived longer than 3 years with positive peritoneal cytology.

Based on previous studies from our institution and others, positive peritoneal cytology is an independent predictor of outcome in patients with gastric cancer despite R0 resection.

From Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, a review of more than 650 patients with gastric carcinoma who had no radiographic evidence of metastatic disease on CT imaging underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, and 31% were found to have occult (subradiographic) peritoneal disease. The highest risk for peritoneal disease was found in patients with visible nodal involvement on CT scan or those with tumors involving the entire stomach (linitis plastica) or tumors at the gastroesophageal junction. Since then, other studies evaluating the predictive value of EUS have shown additional effectiveness in selecting patients at higher risk of having occult metastatic disease for diagnostic laparoscopy. Power and colleagues analyzed 94 patients with localized gastric cancer who underwent EUS and staging laparoscopy and found that those with EUS results of early gastric cancer, defined as T1 or T2 and N0, had a significantly lower risk of peritoneal disease than those with locally advanced disease, defined as ultrasonic T3 or T4 or N positive tumors (4% vs 25%). Based on these data, we routinely recommend laparoscopy to rule out occult metastases only for those with locally advanced disease.

Therefore, at our cancer center, diagnostic laparoscopy is used as part of our standard staging evaluation to identify occult peritoneal metastases for patients with locally advanced gastric carcinoma. These patients undergo separate staging laparoscopy with cytologic washings before initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with positive peritoneal cytology are treated with palliative chemotherapy.

Evolving Experience with Minimally Invasive Gastric Cancer Surgery

The only potentially curative treatment of gastric carcinoma is surgical resection. An appropriate cancer operation requires at least a D1 dissection, although most academic centers throughout the West advocate a D2 dissection. Although a laparotomy is the most common approach for surgical resection of gastric carcinoma, many controversies exist regarding the ideal surgical strategy, including whether and when a laparoscopic approach is appropriate. Laparoscopic approaches for gastric cancer have been accepted slowly, largely because of the advanced technical skills required, combined with the necessary oncologic principles that must be met for oncologically appropriate resection, including the gastric resection and adequate lymphadenectomy. Because this disease is rarely seen except at high-volume cancer centers in the United States, the experience in the United States is therefore still limited.

Overall, the Eastern experience has been instrumental in leading the way to the standardization and acceptance of minimally invasive approaches, in large part because of a higher volume of gastric cancer and early-stage disease that has facilitated the application of this approach. Despite these advances, the laparoscopic approach is still relatively new. In 1992, Ohgami and colleagues reported the first laparoscopic wedge resection for the treatment of early gastric cancer. In 1994, Kitano and colleagues performed the first laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) with a modified D1 lymph node dissection for the treatment of early gastric cancer.

Since then, many reports have shown both the feasibility and oncologic adequacy of minimally invasive approaches when performed by surgeons with high-volume exposure and advanced laparoscopic skills, mostly in Eastern countries. However, laparoscopic gastrectomy for all stages of gastric cancer is gradually emerging in the West, although this progress has been slowed by differences in the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma in the East compared with the West. It was not until 1999 that Azagra and colleagues reported the first laparoscopic total gastrectomy for stomach cancer followed by the first totally LADG with Billroth II anastomosis for cancer in 1993. Table 1 summarizes the published experience with laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of gastric cancer.

| Study | Total Patients (N) | Laparoscopic Surgery (n) | Open Surgery (n) | Operative Mortality in the Laparoscopic Group (n/N [%]) | Lymph Nodes Removed (n) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huscher 2005 | 59 | 30 | 29 | 1/30 (3.3) | 30 ± 14.9 |

| Carboni 2005 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0/20 (0) | 23–47 (range) |

| Dulucq 2005 | 52 | 24 | 28 | 0/24 (0) | 24 ± 12 |

| Weber 2003 | 25 | 12 | 13 | 0/12 (0) | 8 (4–14) |

| Feliu 2007 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 0/23 (0) | 21.3 ± 5 |

| Pugliese 2007 | 147 | 48 | 99 | 1/48 (2.1) | 30 ± 7 (D1) 32 ± 7 (D2) |

| Varela 2006 | 36 | 15 | 21 | 0/15 (0) | 15 ± 9 |

| Anderson 2007 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0/7 (0) | 24 (17–30) (median and range) |

| Orsenigo 2009 | 34 | 34 | 0 | 0/34 (0) | 31 ± 10 |

| Reyes 2001 | 36 | 18 | 18 | 0/18 (0) | 8 (4–14) |

| Azagra 2006 | 101 | 91 | 0 | 5/91 (5.5) | 17 ± 5 (D1) 37 ± 14 (D2) |

| Besozzi 2007 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 3/24 (12.5) | 25 (15–50) |

| Strong 2009 | 60 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 18 |

| Guzman 2009 | 80 | 32 | 48 | 0 | 26 |

Huscher and colleagues have the only Western prospective randomized trial to date looking at laparoscopic gastrectomy for all resectable stages of gastric cancer. In their study, 59 patients with a gastric cancer were prospectively randomized to open subtotal or laparoscopic-assisted subtotal gastrectomy. Patients were matched for pTNM stage. Five-year overall survival rates of 59% versus 56%, respectively, and 5-year disease-free survival rates of 57% versus 55% showed oncologic equivalency of the 2 approaches along with the additional benefits of the laparoscopic approach such as decreased length of hospital stay, reduced blood loss, and earlier resumption of oral intake ( Table 2 ).

| Study | Procedures | Patients (LADG/ODG), n | Mean Operative Time (LADG/ODG), min ± SD | Mean Blood Loss (LADG/ODG), mL ± SD | Oral Intake Resumed (LADG/ODG), Mean Postoperative Days ± SD | Complications (LADG/ODG), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kitano et al, 2002 | LADG vs ODG | 14/14 | 227 ± 7/171 ± 13 | 117 ± 30/258 ± 53 | 5.3 ± 1.5/4.5 ± 0.3 | 14.3/28.6 |

| Hayashi et al, 2005 | LADG vs ODG | 14/14 | 378 ± 97/235 ± 71 | 327 ± 245/489 ± 301 | 3.5 ± 0.8/5.4 ± 1.2 | 35.7/57.1 |

| Lee 2005 [Lee 2005b] | LADG vs ODG | 24/23 | 319 ± 16.2/190.4 ± 39.1 | 336.4 ± 180.3/294.4 ± 156.3 | 5.3 ± 1.4/5.7 ± 2.8 | 12.5/43.5 |

| Huscher et al, 2005 | LADG vs ODG | 30/29 | 196 ± 21/168 ± 29 | 229 ± 144/391 ± 136 | 5.1 ± 0.5/7.4 ± 2.0 | 23.3/27.6 |

| Kim et al, 2008 | LADG vs ODG | 82/82 | 253 ± 49/171 ± 27 | 112 ± 85/267 ± 155 | 3.8 ± 0.7/4.1 ± 0.5 | 22-Sep |

In the United States, the first group to publish their experience with laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer was Reyes and colleagues in 2001. In this retrospective case-matched study, there were no significant differences in extent of lymph node dissection or in intraoperative complications between groups. The laparoscopic approach required a significantly longer operative time (4.2 vs 3.0 hours for the open group), likely because of the learning curve of this procedure. However, in the laparoscopic versus open groups, there was less blood loss, an earlier return to bowel function, decreased postoperative ileus, and a significantly reduced hospital stay (6.3 vs 8.6 days).

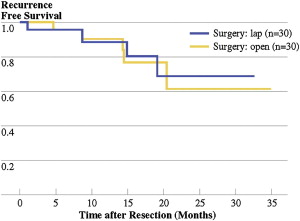

The largest published series of minimally invasive gastrectomy in North America to date comes from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and City of Hope. In the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience, a total of 60 patients were evaluated, including 30 minimally invasive gastrectomies and 30 open gastrectomies ( Table 3 ). Median operative time for the laparoscopic approach was 270 minutes (range 150–485 minutes) compared with 126 minutes (range 85–205 minutes) in the open group ( P <.01). Hospital length of stay after laparoscopic gastrectomy was 5 days (range 2–26 days), compared with 7 days (range 5–30 days) in the open group ( P = .01). Postoperative intravenous narcotic use was shorter for laparoscopic patients, with a median of 3 days (range 0–11 days) compared with 4 days (range 1–13 days) in the open group ( P <.01). Postoperative late complications were significantly higher for the open group ( P = .03). Short-term recurrence-free survival and margin status was similar with adequate lymph node retrieval in both groups ( Fig. 1 ). This series concluded that laparoscopic gastrectomy for carcinoma is comparable with the open approach with regard to oncologic principles of resection, with equivalent margins and adequate lymph node retrieval, showing technical feasibility and similar short-term recurrence-free survival (see Table 3 ).

| Median (Range) | Laparoscopic (n = 30) | Open (n = 30) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | |||

| Billroth II | 20 | 22 | NS |

| Roux-en-Y | 10 | 8 | — |

| Operation time (min) | 270 (150–485) | 126 (85–205) | <0.01 |

| Estimated blood loss (cc) | 200 (50–800) | 150 (100–850) | NS |

| Length of stay (d) | 5 (2–26) | 7 (5–30) | 0.01 |

| Intravenous narcotic use (d) | 3.0 (0–11) | 4.0 (1–13) | <0.01 |

| Early complications (<30 d) | 8 (26%) | 13 (43%) | 0.07 |

| Late complications | 0 (0%) | 6 (20%) | 0.03 |

In the City of Hope experience, a total of 78 consecutive patients were evaluated, including 30 minimally invasive gastrectomies and 48 open gastrectomies ( Tables 4 and 5 ). All laparoscopic resections had negative resection margins and 15 or more lymph nodes retrieved in the surgical specimen, with no difference in the number of lymph nodes retrieved by laparoscopic or open approaches (24 ± 8 vs 26 ± 15, P = .66). The minimally invasive procedures were associated with decreased blood loss (200 vs 383 mL, P = .0009) and length of stay (7 vs 10 days, P = .0009), but increased operative time (399 vs 298 minutes, P <.0001). Overall complication rate for the minimally invasive group was lower although not statistically significant.

| Laparoscopic (n = 30) | Open (n = 48) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery time (min), mean (SD) | 399 (85) | 298 (77) | <.0001 |

| Estimated blood loss, median (range) | 200 (50–900) | 383 (50–2600) | .0009 |

| Length of stay (d), median (range) | 7 (3–32) | 10 (3–67) | .0009 |

| Weight loss at 1 mo (%), mean | 6.77 | 7.74 | .4195 |

| 30-d mortality ( n ) | 0 | 1 | .4262 |

| Conversions ( n ) | 1 | — | — |

| Complications ( n ) | 9 | 22 | .161 |

| Arrhythmia ( n ) | 2 | 8 | — |

| Anastomotic leak ( n ) | 1 | 0 | — |

| Duodenal stump leak ( n ) | 1 | 0 | — |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree