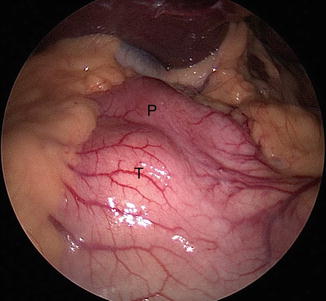

Fig. 20.1

Privette’s anatomic classification of gastric lesions and the distinct surgical approach to them

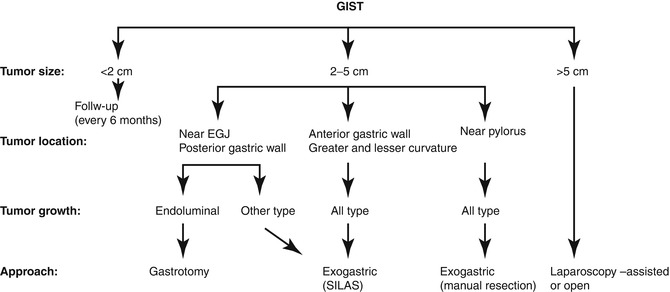

Fig. 20.2

Therapeutic strategy for suspected gastric GISTs (From Sasaki et al. [9], with permission)

Symptomatology and Diagnosis

While GISTs are rare with an annual incidence in the United States of 1,000–2,500 cases per year, they are still the most common non-adenomatous lesion requiring gastric resection. The symptoms are usually related to the size and location of the tumor. Larger lesions usually present as a palpable tumor with symptoms of pressure and abdominal pain. Smaller lesions may present with acute upper GI blood loss or anemia and fatigue. Dysphagia may be the main symptom in lesions occurring at the gastroesophageal junction or at the pylorus. Many GISTs are asymptomatic and may be diagnosed during upper endoscopy for the workup of other conditions. Computed tomography and upper endoscopy are diagnostic for GISTs. The classic findings are a submucosal mass with smooth borders or a rounded appearance or an exophytic lesion. On endoscopy GISTs are firm, smooth, distinct, rounded, or lobulated submucosal lesions. The above findings are so characteristic that they exclude the need for a needle biopsy. Percutaneous biopsy is contraindicated also because of the risk of tumor spillage. In the case of large lesions in need for neoadjuvant therapy or with associated liver lesions suggestive of metastatic disease, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided needle biopsy may be warranted.

Preoperative Planning

The patient’s overall health status and medical conditions should be assessed, and cardiopulmonary comorbidities should be evaluated as for any other major abdominal procedure.

Previous abdominal procedures and operations should be noted, as intra-abdominal adhesions may make a laparoscopic approach far more challenging.

All the pertinent imaging and workup must be reviewed, and after a detailed discussion of all benefits, risks, and alternatives, an informed consent should be obtained.

Surgical Technique

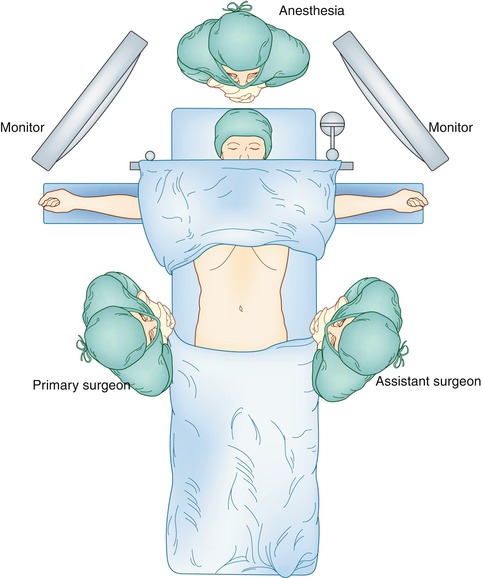

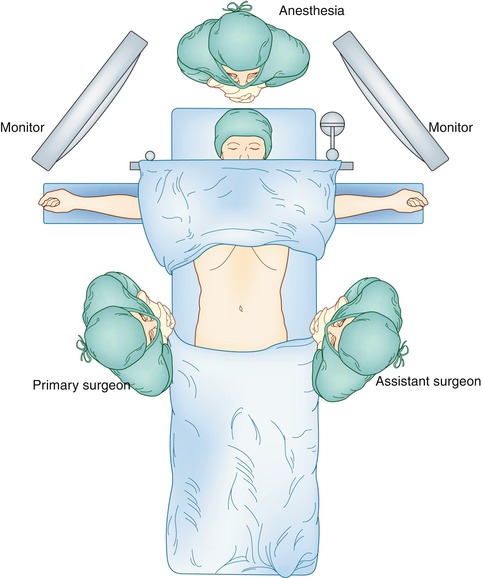

The patient is placed in a supine position with both arms extended. The primary surgeon is positioned on the right side of the patient and the assistant surgery on the left side of the patient. Monitors are placed over the patient’s shoulders bilaterally (Fig. 20.3). As with all foregut procedures, a footboard is placed at the patient’s feet, and the thighs and legs are strapped so as to support the patient during steep reverse Trendelenburg position (Fig. 20.4). A Foley catheter is inserted for precise urine output measurements, and an orogastric tube is inserted to decompress the stomach.

Fig. 20.3

Patient positioning and position of primary and assistant surgeon

Fig. 20.4

A footboard and 2 straps support the patient during steep reverse Trendelenburg

The different approaches shall be described based on the anatomic location of the lesion.

Fundus and Greater Curve

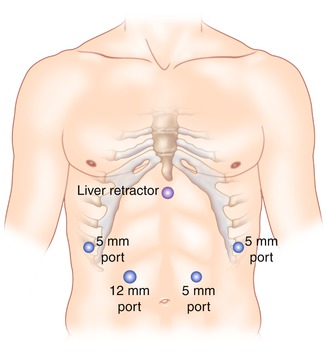

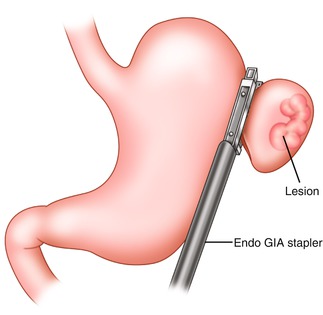

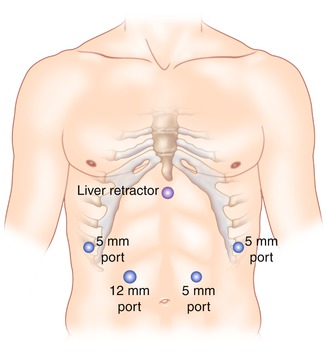

The trocar placement for lesions of the greater and lesser curve of the stomach is shown in Fig. 20.5. Access to the peritoneal cavity is obtained via the left subcostal incision with the use of an optical port under direct vision, and 15 mmHg of carbon dioxide is required to achieve pneumoperitoneum. The other ports are then placed. The camera is inserted in the 5 mm port in the left upper quadrant. The peritoneal cavity is inspected, and the patient is placed in steep reverse Trendelenburg position to expose the stomach and the hiatus. A liver retractor is introduced in to the peritoneal cavity to elevate the left lobe of the liver to provide better visualization. Intraoperative esophagogastroscopy is employed to identify the tumor and its exact location (especially for endophytic lesions) and also to ensure adequate margins. The short gastric vessels are divided with the use of a bipolar energy device with the surgeon retracting the stomach medially and the assistant retracting the omentum and the gastrosplenic ligament laterally. For an anterior wall lesion, the next step is to elevate the anterior wall with atraumatic graspers, and an endoscopic GIA stapler is passed under the tumor incorporating an adequate margin of normal gastric tissue to ensure negative margins (Fig. 20.6). The lesion is placed in a laparoscopic extraction bag. A non-touch lesion lifting method is described by Kiyozaki et al., where traction sutures are placed on the gastric wall over normal stomach 2 cm away from the lesion and are pulled out through the abdominal wall. Thus the tumor is lifted, and the GIA stapler is passed under the tumor to excise it [10]. This method allows the excision of the tumor with decreased risk of tumor spillage and also allows the resection the posterior gastric wall lesions. With adequate mobilization of the stomach, rotation of the stomach allows a posterior gastric wall lesion to face anteriorly and therefore to be removed as an anterior wall lesion.

Fig. 20.5

Trocar placement for extragastric resection of lesions. The surgeon stands on the right side of the table and the assistant on the left

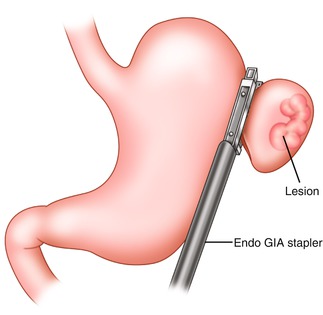

Fig. 20.6

Excision of greater curve lesion using an endoscopic GIA Stapler. Normal gastric tissue is incorporated to ensure negative margins

Larger lesions that are endophytic, requiring more extensive resection, require the placement of a bougie (40 Fr) to ensure luminal patency of the stomach post resection of the lesion.

Antrum/Prepyloric Region

While tumors in the distal stomach or prepyloric region can be excised with the method described above, tumors adjacent to the pylorus are more challenging, due to the difficulty in achieving negative margins without compromising the patency of the pylorus (Fig. 20.7). Posterior lesions limited to the mucosa or submucosa can be excised via an anterior gastrotomy. The access to the peritoneal cavity and port placement is as described above. Upper endoscopy can localize the lesion and assist with the location of the anterior gastrotomy. A horizontal anterior gastrotomy is performed with the use of electrocautery or ultrasonic shears and must be made no closer than 3–4 cm from the pylorus (Fig. 20.8). Traction sutures are placed proximal and distal to the mass, and the lesion is pulled out through the gastrotomy into the peritoneal cavity. The lesion is then removed with an endoscopic GIA stapler (Fig. 20.9). The horizontal incision is closed in a vertical fashion in order to not compromise the luminal diameter of the distal stomach. Traction sutures are placed on the anterior gastric wall, and a GIA stapler is passed below them to staple the anterior defect (Fig. 20.10). The already placed endoscope is then utilized to assess the prepyloric area for bleeding, ensure the luminal patency, and rule out a staple line leak. Larger lesions or lesions that involve the pylorus may not be amenable to wedge gastrectomy, and a resection with reconstruction may be required to avoid stenosis of the gastric outlet.