© Springer Berlin Heidelberg 2015

James H. Feusner, Caroline A. Hastings and Anurag K. Agrawal (eds.)Supportive Care in Pediatric OncologyPediatric Oncology10.1007/978-3-662-44317-0_1818. Knowledge Gaps and Opportunities for Research

(1)

Department of Hematology/Oncology, Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland, 747 52nd Street, Oakland, CA 94609, USA

Abstract

Through the process of researching, writing and editing this book, many knowledge gaps within supportive care for pediatric oncology patients are quite evident, leading to a multitude of possible avenues for research in the supportive care field. Although the majority of research dollars go toward projects whose goal is to improve patient survival through treatment of the underlying malignancy, improvement in supportive care practices has been a vital aspect of the survival gains made to date. Continued assessment and advancement in this field will continue to yield results in improvement in patient quality of life and potentially treatment-related morbidity and mortality. Here we outline some of the areas that necessitate further work.

Through the process of researching, writing and editing this book, many knowledge gaps within supportive care for pediatric oncology patients are quite evident, leading to a multitude of possible avenues for research in the supportive care field. Although the majority of research dollars go toward projects whose goal is to improve patient survival through treatment of the underlying malignancy, improvement in supportive care practices has been a vital aspect of the survival gains made to date. Continued assessment and advancement in this field will continue to yield results in improvement in patient quality of life and potentially treatment-related morbidity and mortality. Here we outline some of the areas that necessitate further work.

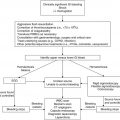

As a general practice, pediatric oncology patients with febrile neutropenia continue to be monitored in the inpatient setting. Although multiple groups have devised risk stratification models, none of these have been validated across populations—further research is required to validate one risk stratification model. As a corollary to this question is the development of standard criteria for outpatient management of febrile neutropenia as well as early discharge criteria for low-risk patients. Although many institutions have developed local protocols to define low-risk populations that can be managed as outpatients after an initial inpatient stay, work remains to determine more universal criteria that can be used across institutions which will both improve patient and family quality of life as well as decrease healthcare costs. Duration of antimicrobial therapy both in patients with febrile neutropenia without a source as well as in those with a proven infection in the face of continued neutropenia is undefined. Many practitioners will continue antibiotics until count recovery even if the patient has no known source of infection and has defervesced. It is unclear if this is necessary and potentially can lead to side effects such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea and development of C. difficile as well as development of resistant bacterial strains. Similarly, for the patient with a known source who has cleared the infection with negative cultures and a sufficient time on antibiotics, it is unclear whether antibiotics can be discontinued or should be continued through some period of count recovery.

Prevention of infection continues to have many questions. The role of bacterial prophylaxis is still unclear and is generally not utilized although may be beneficial in high-risk populations; this question is currently being researched by the Children’s Oncology Group in a study of levofloxacin prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Similarly, it remains unclear if central venous catheter lock therapy, either with ethanol or antibiotics, has universal benefit in the prevention of infection in pediatric oncology patients. Although lock therapy is not standard at our institution, it likely is used in other institutional protocols; whether such a protocol should be universal is unanswered. The benefit of chlorhexidine bathing as a method to prevent central venous catheter infection is also currently being studied by the Children’s Oncology Group. The management of fungal prophylaxis also remains an area with many unanswered questions. Additional biomarkers of invasive fungal infection such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and (1,3)-β-D glucan require further testing and validation in the pediatric oncology population. Similarly, underlying genetic markers which may impact the development of invasive fungal infection are unknown. The utility of empiric antifungal therapy in febrile neutropenia beyond patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and those undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains undefined as to which additional pediatric oncology cohorts may benefit; in addition, appropriate choice of antifungal as well as dose required (prophylactic versus treatment dosing) remains unclear. Additional questions include the optimal fluconazole prophylaxis dose and when anti-mold coverage is important as prophylaxis. Finally, pediatric data are lacking in regard to a preemptive or prophylactic approach with viral infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree