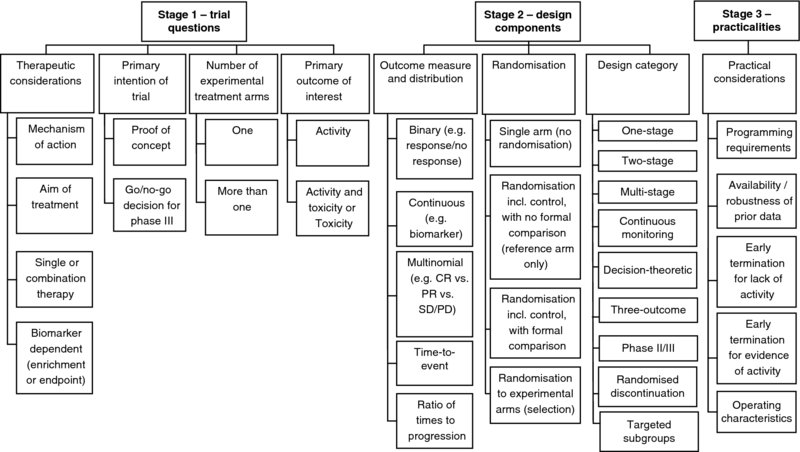

2 Sarah Brown, Julia Brown, Marc Buyse, Walter Gregory, Mahesh Parmar and Chris Twelves Designing a phase II trial requires ongoing discussion between the clinician, statistician and other members of the trial team, so the design can evolve on the basis of information specific to each trial. Central to the approach of identifying an optimal phase II trial design is the thought process introduced in Chapter 1, and presented diagrammatically in Figure 2.1. The process provides an overview of the key stages and elements for consideration during the phase II trial design process. Each of these elements should be worked through in turn in an iterative manner as information derived at earlier stages feeds in to design choices and decisions in the latter stages and consideration of alternative designs. Figure 2.1 Thought process for identifying phase II trial designs. The thought process is made up of three stages: This chapter works through each of the stages and components of Figure 2.1. The choice of trial design depends not only on statistical considerations, but more importantly on the clinical factors relating to the treatment(s) and/or disease under investigation. Discussion of these therapeutic considerations is essential to inform decisions to be made later in the thought process. At the first meeting between the clinician and statistician, discussion of the following points will provide an overview of the setting of the trial and the specific therapeutic issues to be incorporated into the trial design. An important question to ask when beginning the trial design process is ‘how does this treatment work?’ The term ‘cytotoxic’ may be used to describe chemotherapeutic agents, where tumour shrinkage or response is widely accepted as reflecting anti-cancer activity. Many new cancer therapies are, however, targeted at specific molecular pathways relevant to tumour growth, apoptosis (programmed cell death) or angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation). Such ‘targeted therapies’, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors, monoclonal antibody therapies and immunotherapeutic agents, may be ‘cytostatic’. Here, a change in tumour volume may not be the expected outcome: in such cases, tumour stabilisation or delay in tumour progression may be a more anticipated outcome. The mechanism of action of the agent under investigation will inform many subsequent decisions, including the choice of outcome measure and whether or not the trial should be randomised. The aim of the treatment under investigation should be considered both in the context of its mechanism of action and the specific population of patients in which the treatment is being considered. It is important to consider the ultimate aim of treatment, which would inform the outcome measures in future phase III studies, and how this relates to shorter term aims that can be incorporated into phase II trials. For example, in a population of patients with a relatively long median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), the aim of a phase III trial may be to prolong further PFS and/or OS. These would, however, be unrealistic short-term outcomes for a phase II trial; tumour response, which may reflect PFS or OS, can be an appropriate shrinkage aim in a phase II trial. By contrast, where the prognosis is less good PFS may provide a realistic short-term outcome in phase II. It is essential to consider how the longer term and shorter term aims of treatment are related, to ensure an appropriate intermediate outcome measure is chosen in phase II that provides a robust assessment of potential efficacy in subsequent phase III trials. It is important to ascertain whether the treatment under investigation will be given as a single agent or in combination with another novel or established intervention. This distinction can inform the decision as to whether or not randomisation should be incorporated. Where an investigational agent, be it a conventional cytotoxic or a targeted agent, is used in combination with another active treatment it can be very difficult to distinguish the effect of the investigational agent from that of the standard partner therapy; this distinction can be made easier by incorporating randomisation (see Section 2.2.2 for further discussion). Similarly, the assessment of toxicity for combination treatments should also be addressed. Where the addition of an investigational therapy is expected to increase both activity and toxicity to a potentially significant degree, dual primary endpoints may be considered to assess the ‘trade-off’ between greater activity and increased toxicity (see Section 2.1.4 for further discussion). Biomarkers are an increasingly important part of clinical trials. They can be defined as ‘a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention’ (Atkinson et al. 2001). Biomarkers may be considered in the design of phase II trials in two ways. First, a biomarker may serve as an outcome measure. The biomarker may be an intermediate (primary) endpoint in a phase II trial provided it reflects the activity of a treatment and is associated with efficacy; this may form the basis for a stop/go decision regarding a subsequent phase III trial. Decisions regarding the use of biomarkers as primary outcome measures will feed into the decision regarding use of randomisation, considering whether any historical data exist for the biomarker with the standard treatment and the reliability of such data. Where a change in a biomarker reflects the biological activity of an agent, but is not predictive of the natural history of the disease, this alone may be an appropriate endpoint for a proof of concept phase II trial; in such cases a second, go/no-go phase IIb trial may be required to assess the impact of the treatment on the cancer prior to a decision on proceeding to a phase III trial. The use of biomarkers as outcome measures is discussed further in Section 2.2.1. Second, in the era of targeted therapies a molecular characteristic of the tumour that is relevant to the mechanism of action of the treatment under investigation may serve as a biomarker to define a specific subgroup of patients in whom an intervention is anticipated to be effective. This has been done especially successfully in studies of small molecules and monoclonal antibodies targeting HER-2 and related cell surface receptors (Piccart-Gebhart et al. 2005; Slamon et al. 2001). The potential for a biomarker to identify a subpopulation of patients may, however, only become apparent after phase III investigation, as in the case of the monoclonal antibody cetuximab in colon cancer where efficacy is limited to patients with no mutation in the KRAS oncogene (Bokemeyer et al. 2009; Tol et al. 2009; Van Cutsem et al. 2009). Where available, using a biomarker to enrich the population in a phase II trial in this way can increase the likelihood of anti-tumour activity being identified, and thus speed up drug development. By definition, when using a biomarker for population enrichment, the resulting phase II population is not representative of the general population. Interpreting outcomes in the enriched population may, therefore, be more challenging as historical control data may be unreliable; randomisation incorporating a control arm should be considered in such situations. There are, however, potential risks with an over-reliance on biomarkers in phase II trials. If the mode of action of a novel therapy has been incorrectly characterised, the biomarker chosen for enrichment may be inappropriate and could lead to a false-negative phase II trial because the wrong patient population has been treated. Likewise, if a biomarker used to demonstrate proof of principle of biological activity does not accurately reflect the clinically relevant mode of action, the outcome of a phase II trial may be misleading. When a biomarker is the primary endpoint for a trial or used to enrich the patient population of patients it is vital that the biomarker be adequately validated. Where there is insufficient evidence that a biomarker reliably reflects biological activity or identifies an optimal patient group, measurement of the biomarker in an unselected phase II trial population may be appropriate as a hypothesis-generating exercise for future studies. Approaches to trial design that incorporates biomarker stratification are discussed further in Section 2.2.3. In this context, we define the ‘intention’ of a trial not as the specific research question but in the wider sense of classifying trials into two categories: A proof of concept, or phase IIa, trial may be undertaken after completing a phase I trial to screen the investigational treatment for initial evidence of activity. This may then be followed by a go/no-go phase IIb trial to determine whether a phase III trial is justified. Running two sequential phase II trials may, in some cases, be inefficient. The Clinical Trial Design Task Force of the National Cancer Institute Investigational Drug Steering Committee proposed that, where appropriate, proof of concept may be embedded in a single go/no-go trial (Seymour et al. 2010). A model that is increasingly relevant to the development of targeted anti-cancer agents is to incorporate proof of concept translational imaging and/or molecular/biomarker studies within the expanded cohort of patients treated at the recommended phase II dose in a phase I trial. Where clear proof of concept can be demonstrated in this way, there is a blurring of the conventional divide between phase I and IIa studies but the need remains for a subsequent phase IIb trial with the intention of making a formal decision regarding further evaluation in a phase III trial. While this specific point for consideration is not used to group the trial designs given in Chapters 3–7, it is important in considering issues such as primary outcome measures and the use of randomisation. Where a trial is designed as a proof of concept study alone, it may be appropriate to conduct a single-arm trial to obtain an estimate of the potential activity of a treatment to within an acceptable degree of accuracy. Short-term clinical or biomarker outcomes may be appropriate to give a preliminary assessment of activity prior to embarking on a larger scale phase IIb study. Where the aim of the phase II trial is to determine whether or not to continue evaluation of a treatment within a large-scale phase III trial, the ability to make formal comparisons between experimental and standard treatments may be more appropriate, to be more confident of that decision to proceed or not. Similarly, in phase IIb trials outcome measures known to be strongly associated with the primary phase III outcome measure are desirable for robust decision-making. Further discussion on the choice of outcome measures and the use of randomisation is given in Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2, respectively. Whereas historically phase II cancer trials invariably had a single-arm, an increasing number now comprise multiple arms, one of which is often a ‘control’ standard treatment arm. The most common randomised phase II cancer trial designs have a single experimental arm with a control arm so the activity seen in the experimental arm can be compared formally or informally with that seen in the control arm. Randomisation may be appropriate where historical data on the outcome measure are unreliable or when a novel agent is being added to an effective standard therapy (see Section 2.2.2 for discussion). Where multiple experimental treatments are available, or a single treatment that may be effective using different doses or schedules, a phase II trial may be designed to select which, if any, of these options should be taken forward for phase III evaluation. Randomisation can also be used to evaluate multiple treatment strategies such as the sequence of first- and second-line treatments. In these settings assessment of activity of each individual novel treatment, based on pre-specified minimal levels of activity, can be assessed using treatment selection designs which are described in Chapter 5. Where multiple treatments are being investigated in a single phase II trial, with each single treatment in a different subgroup of patients (e.g. treatment A in biomarker-X-positive patients, and treatment B in biomarker-X-negative patients), this should not be considered as a treatment selection trial since only one experimental treatment is being investigated within each subgroup. For the purposes of trial design, such trials fall under the ‘single experimental arm’ category. Further discussion regarding trials of subgroups of patients is provided in Section 2.2.3. The primary outcome of interest will depend on the existing evidence base and/or stage of development of the treatment under investigation, its mechanism of action and potential toxicity. Thus, information obtained from discussion of the therapeutic considerations of the treatment is important in deciding the primary focus of the trial, as well as incorporating data from previous studies of the same, or similar, treatments. At this stage, for the purpose of categorising trial designs, the primary outcome of interest is categorised as being either activity alone, or both activity and toxicity. Designs are also available that address a third option, of considering toxicity alone as the primary outcome measure in a phase II trial. These designs are incorporated with those assessing both activity and toxicity and are described in Chapter 6. Discussion regarding the specific primary clinical outcome measure is given in Section 2.2.1. Where the toxicity of the investigational treatment is believed to be modest in the context of phase II decision-making or the toxicity of agents in the same class is well known, the primary phase II trial outcome measure will usually be anti-tumour activity, with toxicity included amongst the secondary outcome measures. If the toxicity profile of the investigational treatment, be it a single-agent or combination therapy, is of particular concern, the activity and toxicity of the treatment may be considered as joint primary outcome measures, such that the investigational treatment must show both promising activity and an acceptable level of toxicity to warrant further evaluation. Such designs allow incorporation of trade-offs between pre-specified levels of increased activity and increased toxicity, to determine the acceptability of a new treatment with respect to further evaluation in a phase III trial. Emerging cancer treatments have many differing modes of action, which should be reflected in the choice of outcome measures used to assess their activity. While tumour response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) (Eisenhauer et al. 2009) has historically been the most widely used primary outcome measure, non-binary definitions or volumetric measures of response, measures of time to an event such as disease progression or continuous markers such as biomarkers may be more relevant when evaluating the activity of targeted or cytostatic agents (Adjei et al. 2009; Booth et al. 2008; Dhani et al. 2009; Karrison et al. 2007; McShane et al. 2009). When choosing between the many possible primary outcome measures for a phase II trial the key points to consider include the expected mechanism of action of the intervention under evaluation, the aim of treatment in the current population of patients, whether there are any biomarker outcome measures available, the stage of assessment in the drug development pathway (i.e. phase IIa or IIb) and the strength of the association between the proposed phase II outcome measure and the primary outcome measure that would be used in future phase III trials. The chosen outcome measure should also be robust with respect to external factors such as investigator bias and patient and/or data availability. The primary outcome measure of a phase II trial should be chosen on the basis that if a treatment effect is observed, this provides sufficient evidence that a treatment effect on the phase III primary outcome is likely to be seen. The use of surrogate endpoints has been investigated in a number of disease areas, including breast (Burzykowski et al. 2008), colorectal (Piedbois and Buyse 2008) and head and neck cancer (Michiels et al. 2009). While the outcome measures used in phase II trials do not need to fulfil formal surrogacy criteria (Buyse et al. 2000) evidence of correlation between the phase II and III outcome measures is important to ensure reliability in decision-making at the end of a phase II trial. The choice of primary outcome measures for a phase II trial reflects the outcome distribution. This section outlines the various options used to categorise phase II trial designs within Chapters 3–7, according to the distribution of the chosen primary outcome measure (as described in Chapter 1). Response is usually evaluated via a continuous outcome measure, that is, the percentage change in tumour size. This is, however, typically dichotomised as ‘response’ versus ‘no response’ following RECIST criteria (Eisenhauer et al. 2009). Such binary outcomes, categorised as ‘yes’ or ‘no’, may be used for any measure that can be reduced to a dichotomous outcome including toxicity or change in a biomarker. Other outcome measures that may be expressed as continuous, such as time to disease progression, are frequently dichotomised to reflect an event rate, such as progression at a fixed time point. In phase II studies of cytotoxic chemotherapy the biological rationale for response as an indicator of anti-cancer activity is based in part on the natural history of untreated cancers which grow, spread and ultimately cause death. Administration of each cycle or dose of treatment kills a substantial proportion of tumour cells (Norton and Simon 1977) and as such is linked to delaying death (Norton 2001). These principles may be applicable to chemotherapeutic agents which target tumour cell kill, and therefore the endpoint of response may be a relevant indicator of anti-tumour activity. There are inherent issues in the assessment of tumour response, associated with investigator bias, inter-observer reliability and variation in observed response rates over multiple trials (Therasse 2002). These may, to some degree, be alleviated by the incorporation of independent central review of response assessments or the incorporation of a randomised control arm when historical response data are unreliable. The use of classical response criteria for trials of drugs that may not cause tumour shrinkage is likely to be inappropriate and raises questions over the design of phase II trials and the endpoints being used (Twombly 2006). Measures of time to an event such as disease progression or novel endpoints such as biomarkers may be more relevant when evaluating the activity of newer targeted therapies. Nevertheless, because most targeted or biological therapies are selected for clinical development on the basis of pre-clinical data demonstrating at least some degree of tumour regression, tumour response may remain an appropriate outcome measure for novel agents, as acknowledged by two Task Force publications (Booth et al. 2008; Seymour et al. 2010). Continuous outcome measures such as tumour volume or biomarker response may be appropriate and relevant outcome measures for consideration in studies of novel agents (Adjei et al. 2009; Karrison et al. 2007; McShane et al. 2009). The use of biomarkers in clinical trials is becoming increasingly common in the development of targeted treatments with novel mechanisms of action. Only when a biomarker has been validated as an outcome measure of activity, that is, when a clear relationship has been established with a more conventional clinically relevant outcome measure, should a biomarker be used as the primary outcome measure of a phase II trial. The difficulties in identifying validated biomarkers have been highlighted (McShane et al. 2009), in addition to the need for technical validation and quality assurance of the relevant assays. As discussed above, biomarkers may be dichotomised to produce a binary outcome; statistical designs can, however, incorporate biomarkers as a continuous outcome, which may often lead to more efficient trial design. Multinomial outcome measures may offer an alternative to binary outcomes when multiple levels of a clinical outcome may be of importance. For targeted or cytostatic therapies, an alternative to binary tumour response (i.e. response vs. no response) that remains objective may be the ordered categories of tumour response such as complete response plus partial response versus stable disease versus progressive disease (Booth et al. 2008; Dhani et al. 2009). Alternatively activity of an experimental therapy may be evidenced by either a sufficiently high response rate or a sufficiently low early progressive disease rate (Sun et al. 2009).

Key points for consideration

2.1 Stage 1 – Trial questions

2.1.1 Therapeutic considerations

2.1.1.1 Mechanism of action

2.1.1.2 Aim of treatment

2.1.1.3 Single or combination therapy

2.1.1.4 Biomarker dependent

2.1.2 Primary intention of trial

2.1.3 Number of experimental treatment arms

2.1.4 Primary outcome of interest

2.1.4.1 Activity

2.1.4.2 Activity and toxicity (or toxicity alone)

2.2 Stage 2 – Design components

2.2.1 Outcome measure and distribution

2.2.1.1 Binary

2.2.1.2 Continuous

2.2.1.3 Multinomial

2.2.1.4 Time to event

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree