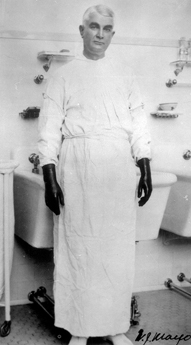

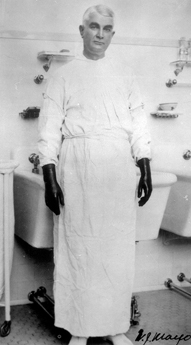

Dr. William Mayo. (By permission of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved)

The story of the first operation for insulinoma is fascinating but tragic. After struggling with recurrent bouts of abdominal pain and a perineal rash that seemed to defy diagnosis for 5 years, Dr. Dickinson Wheelock, an orthopedic surgeon from South Dakota, was referred to the Mayo Clinic by his local physician, Dr. D. A. Gregory, for abdominal pain accompanied by a constellation of additional symptoms. Excerpts of his referral letter are poignant and enlightening.

I think someone picked him for a ‘nut’…about a year ago he noticed that he would develop a tremor, sweating, and nervousness after going without food or after severe exertion. He discovered taking sugar would prevent the recurrence of these attacks…. About three weeks ago I saw him in one of his typical attacks caused by his going without breakfast and not having enough candy. He resembled an acute alcoholic, great motor activity, dancing and talking, squinting and frowning, apparently having hallucination of sight and hearing, negativistic and difficult to control. I had great difficulty in getting him to take a coca cola full of syrup, but after taking it, he recovered in about five minutes…. Several times he has become comatose…. This man is not a nut but has become rather soured on his professional confreres because he has not got to first base on a diagnosis… [He] is an exceptional case and I can find nothing about hypoglycemia. Try and get someone interested in him and don’t let him die because he sure will if he goes too long without carbohydrate. (Referral letter to Dr. Davis at Mayo Clinic, 1926 [1])

Dr. Wheelock remained in hospital for months under the care of Dr. Russell M. Wilder, a noted endocrinologist. True to the story, the patient’s hypoglycemia was so severe as to require an estimated 25 g of glucose per hour to ameliorate his symptoms. But no medical therapy could resolve his problem, and Dr. Will Mayo was consulted, principally because his surgical expertise was abdominal and pelvic surgery (Fig. 1). On Saturday, December 4, 1926, surgical exploration was undertaken. Portions of Dr. Mayo’s operative note follow:

Fig. 1

Dr. William Mayo at the scrub sink. (By permission of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved)

The pancreas was normal from the head to the top of the spine and from then on it curved like a shrimp and seemed to grasp the spine. The consistency of this portion was hard, irregular. Secondarily there is a tumor the size of an orange in the middle of the right lobe of the liver…. A specimen about five cm wedge-shaped by about 4 cm at the point of the wedge was removed for diagnosis.

Extracts of the tumor and the normal liver were subsequently prepared which were injected intravenously into rabbits—and behaved exactly like an insulin preparation. Sadly, Dr. Wheelock continued to suffer symptoms when not receiving his glucose infusion, and remained hospitalized until he died on January 3, 1927. Autopsy confirmed carcinoma of the pancreas with metastases to the liver, intestine, and regional lymph nodes.

Pertinent to Dr. William Mayo’s involvement in endocrine surgery is his first and only experience with thyroid surgery. In his own words, “Dr. Will” recounts this story as part of his touching eulogy for Dr. Henry S. Plummer in 1938 [2]:

Away back in 1889, when St. Mary’s Hospital was first opened, one of the earliest operative cases we had was one of goiter, the largest thyroid tumor I have ever seen, in J.S., a Scotchman aged about sixty-two years…. The huge tumor was a degenerating thyroid, and the man had great difficulty in breathing and was in a very serious condition. I had heard something about the use of iodine to cause shrinkage of large thyroid tumors, and I injected this tumor with iodine in a number of situations…. The patient’s condition was precarious, and I knew, that whatever happened, the tumor must come out. We put him on the table, using a small amount of the old ACE anesthetic mixture (alcohol one part, chloroform two parts, and ether three parts), incised the skin and superficial tissues…and rapidly enucleated the tumor with our hands. The bleeding was profuse…and knowing the efficacy of turpentine to stop this type of bleeding…the sponge soaked with turpentine was placed in the cavity from which the goiter had been removed, and the wound was sutured tightly over it…a large dressing was bandaged in place as tightly as the patient’s breathing capacity would permit. After some days the incision was opened and the sponge removed. The wound healed perfectly and the patient made a fine recovery…. My brother, who recently had graduated from Northwestern University, in 1888, assisted me in the operation. This was the beginning and end of my work in the goiter field. The problem passed entirely over to my brother.

While the stories of the first insulinoma ever operated, and the collaboration of the Mayo brothers faced with resecting a huge goiter as their first thyroid operation are amazing and remarkable, the sustained prominence of William and Charlie Mayo goes far beyond. Their incredible, single-minded, lifelong dedication to serving mankind laid the foundation for what evolved into the most prestigious medical center worldwide . This account focuses on “Dr. Will”, as “Dr. Charlie’s” career is summarized elsewhere. But their success, fame, and respect were earned and shared equally. Their story can hardly be more eloquently recounted than to rely largely on their own words.

Will and Charlie were fortunate to have exemplary parents as role models—their father, William Worall Mayo, was a highly respected doctor. They recognized and appreciated their heritage. Charlie once stated, “the biggest thing Will and I ever did was to pick the father and mother we had” [3]. Will said, “It never occurred to us that we could be anything but doctors…. From the beginning Charlie and I always went together. We were known as the Mayo boys” [3]. They learned the principle of noblesse oblige from their father. Will set lofty goals for himself—at the age of 22, after working in his father’s medical office for 1–2 years, Will told a friend of his father’s that “I expect to remain in Rochester and become the greatest surgeon in the world” [3]. Will eventually graduated from medical training at the University of Michigan on June 28, 1883, the same year that a devastating tornado ravaged through Rochester which prompted the building of St. Mary’s Hospital (SMH), currently supporting 1400 beds. Charlie earned his medical degree from Chicago Medical College (subsequently Northwestern University) on March 27, 1888.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree