Chapter 8 ISSUES IN RURAL AND REMOTE LOCATIONS

INTRODUCTION

Australia has always taken pride in its rural heritage, and much of its modern-day nationhood grew from the values that emanated from this agricultural background. One-third of Australia’s population is spread throughout rural and remote regions. The population in these regions also includes a significant number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and although specific cultural issues are addressed in Chapter 6, problems within rural and remote regions are magnified for these people because their health levels and socioeconomic status are markedly lower than that of other Australians.

DEMOGRAPHICS

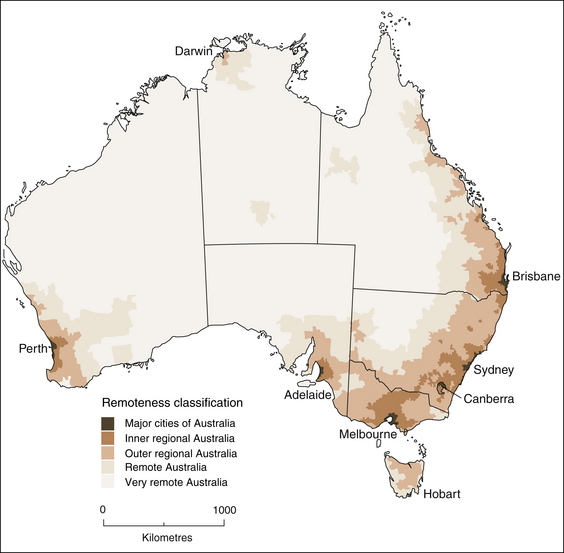

A significant proportion of Australia’s older population lives in areas classified as regional, rural and remote. This means all those areas outside major cities, such as regional towns, coastal settlements, small inland towns, farming communities and what is referred to as ‘the bush’ or ‘the outback’. The Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) remoteness areas classification (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001) gives one of five remoteness categories to areas depending on their distance from different sized urban centres, where the population size of the urban centre governs the range and types of services available (see Fig 8.1). The Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) (Department of Health and Family Services 1994) classifies rurality and considers settlement at five levels. At level 1 there are populations between 200 and 5000, at level 2 there are populations between 5000 and 17,999, at level 3 there are populations between 18,000 and 49,999, at level 4 there are populations between 49,999 and 250,000, and at level 5 there are populations over 250,000.

The 2006 census (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2007) established that 24% of older people live in inner regional areas, 11% in outer regional areas, 1.2% in remote areas and 0.5% in very remote areas. Generally, 36% of older people live outside of the metropolitan cities, whereas 33% of people under 65 years of age live in the same areas. The figures for Indigenous Australians add an important perspective when discussing the mental health needs in rural and remote locations. Although, overall, Indigenous people only constitute 2.5% of the total Australian population, they make up 12% of the population in remote areas and 45% of the population in very remote areas. Another factor to consider is the expanding number of retirees moving from the cities to coastal and rural locations. They usually retire to these areas because of the attractive features of rural communities, such as a slower pace of life, friendliness and cheaper accommodation, so their retirement funds go further. However, these communities often do not have the infrastructure to cope with the perils of ageing on a large scale.

THE MENTAL HEALTH OF OLDER PEOPLE IN RURAL AND REMOTE LOCATIONS

In regard to mental health, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2008b) reported that there are no statistically significant interregional differences in the prevalence of major psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. In fact, men aged 65 years and over were significantly less likely to experience depression than their urban counterparts. However, the National Health Survey (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006) collected information on psychological distress by asking 10 questions about emotional state in the four weeks prior to interview. People with very high levels of psychological distress potentially have the need for help from a health professional. Men in rural and remote areas were 1.2 times more likely than men in metropolitan areas to show high to very high levels of psychological distress. Men aged 46–64 years scored the most distress, closely followed by men 65 years of age and over. Older women scored the highest amount of psychological distress for women. When the scores of men and women were combined, the 65 years and older cohort had the most psychological distress overall.

ACCESS TO MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

Australians in rural and remote areas do not have the same level of access to quality health services as their urban counterparts. This situation is compounded for mental health services (Perkins 2008). There is a dire shortage of specialist mental health professionals and often a high turnover of staff. Additionally, knowledge and interest regarding mental health issues among generalist healthcare staff is often limited. For example, they may not be up to date with current, effective treatments. When the responsibility for the management of an acutely ill person falls onto primary care providers, such as general practitioners (GPs), ambulance/retrieval officers, hospital emergency staff, Aboriginal health workers and in some circumstances police, the likelihood of ideal outcomes for the older person may be greatly reduced, despite the best intentions of the people involved. In the primary care setting, mental health problems are usually complicated by associated chronic physical conditions and/or drug and alcohol abuse, making the situation even more difficult for underresourced health services. However, with mental healthcare, there may be some advantage in rural and remote areas including closer integration between the GP, hospital care and community care, and easier access to some community services and residential aged care facilities (RACFs) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2000).

Due to the lack of specialised services in rural and remote areas and inability of general health services to take on older people with serious mental health problems, a large proportion of the burden of care falls onto families and other informal caregivers. Even when services do exist, there can be a reluctance to use them due to the previously described stoicism, privacy and confidentiality reasons. Support groups can be set up, but if travel time and transportation difficulties prevent involvement in this type of activity, carers can be referred to online services or websites that mental health organisations have set up (Dow et al 2008). These provide excellent information and support for older people and their carers. Crisis lines also have an important role to play in assisting people in emergency situations.

Greater difficulties in accessing healthcare due to distance, time, cost and transport availability, and longer delays in accessing services, can make mental health problems more serious, resulting in admission to hospital. People in rural and remote areas have higher rates of hospitalisation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2008a). Admission to the local hospital or a RACF for a mental health problem may not be an ideal option if it is not resourced to meet the older person’s needs. However, due to lack of availability of and inability to gain access to mental health beds in the larger centres, older people who are acutely ill with primary psychiatric diagnoses are sometimes treated in general beds of the local hospital with staff who may not have the knowledge of how to treat a mental health problem. The older person and their family may be very uncomfortable with this outcome. Concern could be about privacy and confidentiality issues.

Through lack of understanding, prejudices against an individual and their family can easily develop, with long-term consequences. In a small community, anonymity is difficult. People may be very sensitive to the stigma attached to mental health problems and experience feelings of shame, humiliation and embarrassment. In such circumstances, it may be prudent to use services in other areas if appropriate or available. Another issue that may arise in a small community is there could be conflicting roles and boundaries between the healthcare workers and the older people — they may be related or socially connected. In such situations, the health professional needs to explain to the older person and their relatives what their professional role is and how they are legally and ethically bound in regard to privacy and confidentiality (Hungerford 2006).

If the situation is an emergency or dangerous, the hospital may not be able to admit the person, and in these situations police cells are sometimes used. Although this might only occur in extreme circumstances, it could be very traumatic and humiliating for the older person. Another option is to be admitted to distant city facilities. Specialist care may be received, but the disadvantage could be separation from families, communities and social networks whose support is needed in times of mental health problems (Hungerford 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree