Issues in Nutrition and Hydration

Christine S. Ritchie

Elizabeth Kvale

The issues surrounding artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) pose challenges for clinicians, patients, families, and society. Legal precedent and ethical principles guide medical practice; yet with regard to critical questions in this area our scientific base for establishing benefit or harm is so primitive and methodologically inadequate that evidence-based decisions are illusory. Decisions regarding the use of hydration and nutrition in palliative care often boil down to an honest if imperfect discussion of the potential harm and benefit of nutrition and hydration in a particular setting, filtered through the values of each patient and their family.

What is Nutrition and Hydration?

Definitions

Artificial hydration is the provision of water or electrolyte solutions by any nonoral route. Artificial nutrition includes total parenteral nutrition (TPN), enteral nutrition (EN) by nasogastric tube (NGT), percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy jejunostomy (PEG-J) tube, gastrostomy tube, or gastrojejunostomy tube.

History

In the 1920s, continuous infusion of i.v. glucose was introduced in humans. It was not until the 1960s that parenteral nutrition was used, first in seriously ill adult surgical patients and then in children and adults with short bowel syndrome (1). These children, who before these therapies died of starvation, were able to live for years, sustained with artificial nutrition. Parenteral nutrition use then expanded to many other patient populations, often without clear or well-established indications. Only in the past decade has some light been shed in critical care settings as to when TPN is beneficial and when it may be more harmful (2, 3).

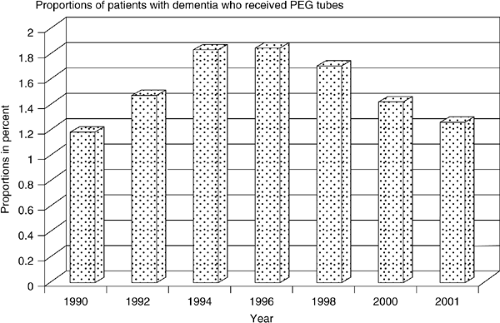

In the late 1970s, gastrostomies began to be performed and were often used for swallowing problems in children (4). Their use became widely generalized to adults such that EN is now commonly used among patients with stroke, neurologic disease, and cancer (5). Between 1988 and 1995 the number of tubes placed in the United States doubled; in 2000, more than 216,000 tubes were placed. Recent data from Veterans Administration and Medicare database reviews suggest a stabilization of this trend in some settings (Fig. 68.1)).

Whereas i.v. hydration is a well-established part of medical practice, its role in end-of-life care remains less clear. IV hydration is often used for treatment of terminal delirium and agitation. Whether it is beneficial, and if so, at what rate of infusion, remains an area of controversy.

Ethical and Legal Framework

Nutrition and hydration decisions may be more difficult for some families than ventilator support or cardiac resuscitation. Families may equate foregoing of artificial nutrition with starvation. The potential harms associated with artificial nutrition (such as restraint use, immobility, and decreased social contact) are often not considered. Because of the dearth of good scientific data to assist clinicians in addressing whether or not artificial nutrition has meaningful benefit, it is often difficult to provide guidance to patients’ families.

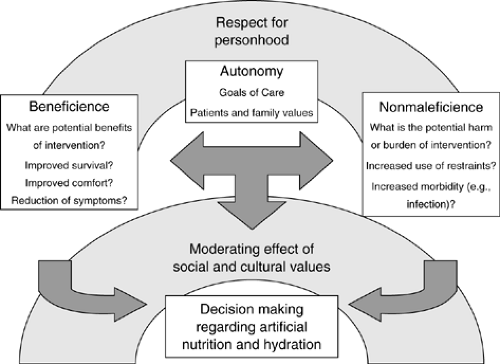

In medicine, ethical principles guide how a patient should be treated or how a treatment dilemma should be handled. The ethical principle of autonomy states that a person should have the ability to govern oneself. This principle was applied in the court decisions of Barber in 1983, Bouvia in 1986, and Cruzan in 1990, all of which stated that competent adults should be the final arbiters of decisions regarding their own health care. If nutritional support is unwanted, then providing artificial nutrition does not adhere to the principle of autonomy and lessens patient dignity. Beneficence is the ethical principle that states that physicians should always provide care that benefits the patient. In the case of artificial nutrition, the physician needs to ask if the artificial nutrition is actually “doing good” for their patient. The principle of nonmaleficence addresses the complimentary principle that one should “do no harm”—primum non nocere. In the case of ANH, physicians must weigh the potential for this medical treatment to harm their patient in any way. If this treatment was contributing to more harm than benefit, than the principle of nonmaleficence would support its discontinuation (Fig. 68.2)).

The argument for the discontinuation of nutritional support states that ANH are indistinguishable from other medical treatments. In the 1990 Cruzan decision, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that “the law does not distinguish artificial feeding from other forms of medical treatment” (6). The right of patients to refuse this treatment is supported, and within this framework artificial nutrition is considered medical intervention

and not basic care. Withdrawing artificial nutritional support and allowing a patient to die is not considered equivalent to euthanasia. In the former instance, the goal of discontinuing therapy is to remove burdensome interventions; in the latter, the intended result is the death of the patient. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by the Schiavo case, public acceptance of these distinguishing features in nutritional support varies greatly. Furthermore, some faith communities take issue with the distinction between artificial and basic nutrition.

and not basic care. Withdrawing artificial nutritional support and allowing a patient to die is not considered equivalent to euthanasia. In the former instance, the goal of discontinuing therapy is to remove burdensome interventions; in the latter, the intended result is the death of the patient. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by the Schiavo case, public acceptance of these distinguishing features in nutritional support varies greatly. Furthermore, some faith communities take issue with the distinction between artificial and basic nutrition.

In addition, much legal confusion persists because advance directive statutes may make it more difficult for a person capable of making decisions to prospectively forego ANH, and many state statutes are poorly written and confusing (7).

Indications

No clear palliative indications exist for artificial nutrition. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) endorses PEG tube placement for prolonged tube feeding (specifically more than 30 days), and nasogastric feeding when enteral feeding is required for shorter periods (Table 68.1). In practice, PEG tubes are placed for a variety of different clinical conditions, including dysphagia, prolonged illness, anorexia, neurologic/psychiatric disorders, oropharyngeal or esophageal disorders or cancers, or increased nutritional needs that the patient is unable to meet with oral intake. Studies show that neurologic illnesses (e.g., dysphagia following stroke, dementia), cancer (obstruction secondary to tumor, postradiation, postchemotherapy, or postresection), and the prevention of aspiration account for most placements (8, 9, 10).

Indications for artificial hydration are relatively straightforward in critical care settings or when an otherwise healthy patient presents with volume depletion. Indications for hydration at the end of life have not been established. In the acute care setting, parenteral hydration is routinely given. In the hospice setting, parenteral hydration is not routine, but may be considered in instances where the patient is experiencing neuropsychiatric symptoms such as delirium, myoclonus, and agitation.

Figure 68.2. Integration of ethical principles into decisionmaking regarding artificial nutrition and hydration. |

With regards to ANH, the scientific literature lacks high quality randomized trials that might yield clear indications to guide practice.

Benefits and harms are often gleaned from imperfect evidence from heterogeneous populations.

Benefits and harms are often gleaned from imperfect evidence from heterogeneous populations.

Table 68.1 American Gastroenterological Association Guidelines on Enteral Feeding | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Potential Benefit of Artificial Nutrition

Common rationale for use of artificial nutrition includes improved survival, comfort, reduction in pressure ulcers, and reduction in aspiration. Although most of the studies performed to date are compromised by substantial methodological problems, none have consistently demonstrated improved outcomes in these arenas with the exceptions of improved survival for short bowel syndrome, decreased hepatic encephalopathy in alcoholic cirrhosis, decreased length of hospital stay in hip fracture patients, and decreased postoperative complications of patients with gastric cancer given artificial nutrition preoperatively (11, 12). Although no controlled trials exist, follow-up studies suggest increased survival of patients in persistent vegetative state who are likely to die within weeks without artificial nutrition, but may live for many years with artificial nutrition (13). There is also moderately strong evidence that artificial nutrition can prolong life when it is used in short-term critical care (14). A summary of the levels of evidence for benefit from artificial nutrition is given in Tables 68.2 and 68.3.

Table 68.2 Levels of Evidence for Artificial Nutrition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Survival

A number of retrospective studies and a few prospective studies have been performed in patients to ascertain survival benefit in patients receiving artificial nutrition. The largest study to date was a retrospective review by Grant et al. of 81,105 medicare beneficiaries who received gastrostomies in 1991. No comparison group was identified for this study. Cerebrovascular disease, neoplasms, fluid and electrolyte disorders, and aspiration pneumonia were the most common primary diagnoses. The mortality rate at 1 and 3 years was 63.0–81.3%. The median survival for was 28.9 weeks for women and 17.6 weeks for men. At 30 days, primary diagnoses of malnutrition and fluid and electrolyte disorders, and secondary diagnoses of swallowing disorders, dementia, or cerebrovascular disease were characterized by the lowest mortality rates. Thirty-day mortality rates were highest among those with primary diagnoses of nonaspiration pneumonia or influenza, and secondary diagnoses of congestive heart failure, or any neoplasm (8). Rabeneck et al. studied 7369 patients receiving PEG tubes at VA facilities between 1990 and 1992. In this retrospective cohort study, 23.5% died during their index hospitalization. The median survival of the full cohort was 7.5 months from the time of tube placement. The overall mortality rates at 1, 2, and 3 years were 59, 71, and 77%, respectively. The highest mortality rates were observed for patients with lung or pleural cancer (46.4%), followed by esophageal cancer (20.8%) and head and neck cancer (18.8%) (15). Survival decreased with increasing age. The median survival across clinical diagnostic categories was 13.9 months for cerebrovascular disease, 13.4 months for other organic neurologic diseases, 9.6 months for nutritional deficiency, 8.0 months for head and neck cancer, and 4 or fewer months for all other cancers. Among 674 older (age >50) adults referred to a community gastroenterology group for PEG insertion over a 10-year period, mortality rates at 1, 2, and 3 years were 54.3, 73.2, and 84.5%, respectively. Like

Rabeneck’s study, the overall median survival was between 6 months and 1 year; however, those receiving tube feeding in this cohort were much more likely to be patients with stroke or other neurologic conditions. Very few of the PEGs were placed in patients with cancer. Risk factors for mortality in this cohort were being male, having feeding difficulty, having diabetes, being referred from a hospital and being 80 years of age or greater (16). Similar to Grant’s cohort, dementia was not an independent risk factor for decreased survival. Because these studies used large databases, identification of truly comparable control groups would have been challenging. Nevertheless, because there was no comparable control group, the impact of gastrostomies on survival could not be ascertained.

Rabeneck’s study, the overall median survival was between 6 months and 1 year; however, those receiving tube feeding in this cohort were much more likely to be patients with stroke or other neurologic conditions. Very few of the PEGs were placed in patients with cancer. Risk factors for mortality in this cohort were being male, having feeding difficulty, having diabetes, being referred from a hospital and being 80 years of age or greater (16). Similar to Grant’s cohort, dementia was not an independent risk factor for decreased survival. Because these studies used large databases, identification of truly comparable control groups would have been challenging. Nevertheless, because there was no comparable control group, the impact of gastrostomies on survival could not be ascertained.

Table 68.3 Recommendation Classifications and Levels of Evidence | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Comfort

The small body of literature evaluating patient symptoms at the end of life suggests a relatively low prevalence of hunger (17). In McCann’s study of 32 patients in a comfort care unit, 63% denied hunger entirely, while 34% reported hunger during the first quarter of their course in the unit. In all patients reporting either hunger or thirst, these symptoms were consistently and completely relieved by oral care or the ingestion of small amounts of food and fluid. In a case study of a patient refusing nutrition and hydration, the patient experienced no discomfort and died peacefully (18). A survey of Oregon hospice nurses found that among those who had cared for patients who declined nutrition and hydration, the majority reported the ensuing death to be peaceful (19).

Studies of healthy volunteers engaged in fasting report resolution of hunger in less than 24 hours. The resulting ketosis is associated with relief of hunger and a mild euphoria. Animal studies suggest that ketosis may also have a mild analgesic effect. When ketosis is minimized by small feedings, hunger may persist (20).

Reduction in Pressure Ulcers

There is some evidence that malnutrition is positively correlated with pressure ulcer incidence and severity (21, 22). However, only two nutrition intervention studies for pressure ulcer prevention or treatment included artificial nutrition. Hartgrink et al. performed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 140 patients with fracture of the hip and an increased pressure ulcer risk. The intervention group was treated with standard hospital diet and additional NGT feeding administered overnight. The comparison group received the standard hospital diet alone (23). No significant difference was found between the groups. Chernoff et al. utilized artificial nutrition in an RCT of 12 tube-fed patients with pressure ulcers. The treatment comparison, however, was amount of protein intake, not tube feeding (24). Thus, it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions on the effect of enteral and parenteral nutrition on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree