and Karl Reinhard Aigner3

(1)

Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(2)

The Royal Prince Alfred and Sydney Hospitals, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(3)

Department of Surgical Oncology, Medias Clinic Surgical Oncology, Burghausen, Germany

A large range of tests is now available to help detect cancer. Some of the most useful of these became available only during the last decade or two of the twentieth century. These range from screening tests, which may help detect the possibility of cancer in people who are at risk but without any symptoms, to organ-imaging tests when symptoms are being investigated. Helpful tests include X-rays, CT scans, ultrasound scans, isotope scans, MRI scans and PET scans. Each of these may reveal the presence, the site and likely dimensions of a deep-seated tumour. Endoscopic tests that use flexible mirrored endoscopic tubes allow the operator to look at, photograph and even biopsy lesions in the alimentary tract, thorax, peritoneal cavity or in other body cavities. A number of blood and serum tests may reveal evidence of reactions to a tumour somewhere in the body. The ultimate investigation, however, is a biopsy because microscopic examination of biopsied material can very often tell the type of malignant cells and the organ or tissue from which they originally developed, as well as the degree of anaplasia or potential aggressiveness of the cancer.

7.1 Screening Programmes

Screening programmes are simple, non-invasive and relatively inexpensive methods of detecting early cancers in people in high-risk categories. Early detection before symptoms or signs of cancer have become evident results in significantly better prospects of cure. When certain cancers are known to have a high incidence in a community, governments and health authorities have established ongoing screening programmes in many countries.

7.2 Screening Tests

7.2.1 The Cervical Smear or “Pap” (Papanicolaou) Test

One of the first, and still one of the most useful, specific screening tests is the Papanicolaou (cervical smear) test for detecting early cancer of the cervix of the uterus. Cancer of the cervix is the most common cancer of the uterus. Women over the age of 40 and especially those who have had several sex partners or several pregnancies are at increased risk for this type of cancer, and many such women now have a cervical smear test every year. Women who have been exposed to infection with the human papillomavirus, especially sex workers who have had multiple male partners, have the greatest risk and should be tested more frequently. This test has the advantage of being simple, painless, cheap and, in most cases, highly reliable. In this test a swab or scraping is taken from the uterine cervix through the vagina. Fluid from the swab or scraping is smeared over a glass slide and examined for cells. If malignant cells are found, cancer may be detected early and treated with good results. Other abnormal cells may suggest pre-malignant changes that could become cancer if not treated, so simple treatment at that stage can often prevent a cancer developing.

7.2.2 Occult Blood Tests

A number of chemical and other tests have been used to detect small amounts of blood in the faeces. As stated earlier, blood in the faeces that is not obvious to the naked eye is called “occult blood”. Its presence indicates some abnormality in the stomach or bowel that might be a cancer or possibly a pre-cancerous condition such as a polyp. Occult blood tests are not always reliable and sometimes produce false-negative and false-positive results. Positive tests can be caused by a number of inflammatory or other benign conditions. However, occult blood tests can be useful screening tests to help detect people who are most at risk of cancer and help determine those in need of further investigation. For people with a high risk of bowel cancer, regular screening of the colon and rectum by colonoscopy is advisable.

7.2.3 Gastro-Oesophageal Screening

For people in countries where oesophageal cancer is common, gastro-oesophageal screening by regular endoscopy is advisable. In recent years in Western countries, Barrett’s ulcer of the lower oesophagus has become more common. Barrett’s ulcer is an ulcer in the lower oesophagus associated with long-standing gastro-oesophageal reflux. An unhealed Barrett’s ulcer is now regarded as a pre-malignant condition requiring regular endoscopic observation for early detection of a malignant change.

Although there is no single screening test that is totally reliable, a number of tests can be combined to help detect early breast cancer.

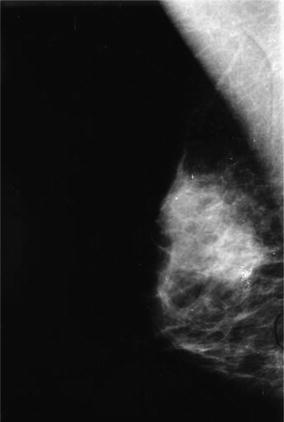

7.2.4 Breast Screenings: Mammography

Other than skin cancer, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in most Western countries. Although there is no single screening test that is totally reliable, a number of tests can be combined to help detect early breast cancer. These include the teaching of self-examination and examination for lumps in screening clinics by a doctor or specially trained nurse. Mammography, ultrasound studies and biopsy using a fine needle or similar instrument to aspirate or otherwise remove a sample of fluid or cells from any suspicious lump for microscopic examination are important screening tests. These are often performed in special clinics supported by government-funded screening programmes. Most large cities in developed societies now have breast-screening clinics in a city hospital or elsewhere in conveniently located central positions (Figs. 7.1 and 7.2).

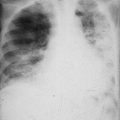

Fig. 7.1

(a, b) Photograph and illustration of mammography. Small-dose X-rays are taken with the breast held firmly between two plates

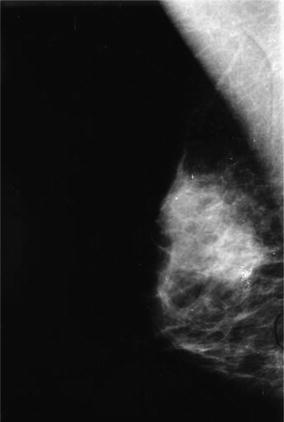

Fig. 7.2

Mammogram showing a rather dense area of breast with a cluster of spicules of calcification suggestive of breast cancer

7.2.5 Skin Cancer Screening: Especially the “Mole Check”

In countries where skin cancer is common, annual “mole checks” are often arranged for members of clubs or particular workforces. This is now commonly practised in many Australian surf clubs. Although called “mole checks”, with particular interest in detecting early melanoma, many “non-mole” pre-malignant or early malignant lesions of skin are detected, especially hyperkeratoses, basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas.

7.2.6 PSA Screening Test

Other than skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer affecting men in Western societies. It is not common before the age of 50 but thereafter becomes increasingly common in older men. Previously, digital rectal examination (DRE) with a gloved finger to detect evidence of a hard or lumpy prostate was the only useful screening test but the prostate-specific antigens (PSA) blood test is now commonly used. The PSA is a simple test in which a raised level is suggestive of a prostate disorder that might be cancer. PSA tends to increase naturally with increasing age in all men. At age 50, the upper level should not be above 3 ng/mL; at 60 it should not be above 4 ng/mL. Higher levels indicate an abnormality of the prostate, most commonly benign prostatic hyperplasia, but progressively increasing levels (up to 6, 8 or 10) or greatly increased levels above about 12 are more suggestive of cancer. Prostate biopsy might be indicated when there is a progressively rising PSA or when the initial PSA is significantly elevated, even if no lump or other abnormality can be detected by DRE.

7.2.7 Genetic Testing

The genetic basis for a familial incidence of some types of cancer such as some cases of breast, prostate, ovary and large bowel cancers is becoming better understood. In most cases, cancers associated with inheritance of abnormal tumour suppressors and oncogenes tend to appear at an earlier age than those not found to have a hereditary association.

Genetic testing is time consuming and, as yet, has not become available for general cancer screening, but there is potential for early detection and cancer prevention in individuals with a strong family history of a particular cancer. People found to be at special risk should be referred to special counselling and risk management clinics.

7.3 Organ Imaging

7.3.1 X-Rays

Radiological studies or X-rays are a relatively old but still useful method of medical examination for cancer. Techniques are constantly being improved and the doses of X-rays needed are becoming smaller. X-ray films are only able to detect spots or lesions that have different permeability for X-rays than that of normal tissue in the region. This difference is seen as a relatively light or relatively dark shadow on a film. For example, X-rays pass easily through air in the lungs or gas in large bowel and this is shown as a dark shadow on a film. If a tumour is present in a chest X-ray, the X-rays will penetrate the tumour tissue less well than the air-filled lungs so that the tumour will show as relatively lighter or whiter part in the area normally showing as dark shadow from the air-filled lungs. On the other hand, X-rays are blocked by dense bone that shows as a white area on film. If a tumour is present in bone, the bone destruction may show as relatively dark or grey areas in the bone that is otherwise white due to lack of penetration of normal bone by X-rays. Other tissues such as muscle and fat are intermediate between the dark shadow of air and the white shadow of bone in their penetration by X-rays. These tissues are of similar consistency and have similar penetration to X-rays as do tumours so that it is not so easy to detect tumour shadows in soft tissues by simple X-rays, and more sophisticated investigations may be required.

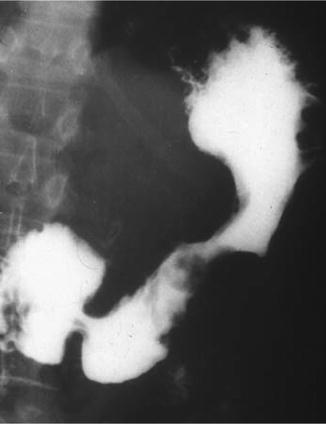

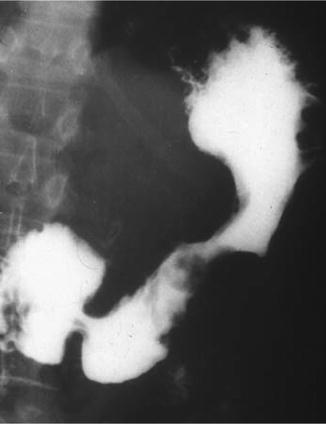

7.3.2 Barium (Baryum) and Iodine Contrast X-Rays

Barium (baryum) or iodine compounds and some other materials (often called “dyes” or “contrast” material) are impervious to X-rays, and these are often used in the body to outline cavities that are otherwise not easily seen in a plain X-ray film. A barium meal is a barium sulphate mixture swallowed into the stomach. This outlines the shape of the stomach. If a cancer is present, it may show as an abnormality in the shape or in the outline of the stomach. Similarly, a barium enema in the lower bowel may allow X-rays to help detect a cancer in the colon or rectum (Figs. 7.3 and 7.4).

Fig. 7.3

A barium (baryum) meal X-ray showing a “filling defect” of the greater curvature of the stomach due to a gastric cancer

Fig. 7.4

A barium (baryum) meal X-ray showing a “filling defect” of the greater curvature of the stomach due to a gastric cancer

Iodine compounds are also used as “contrast” material as they are excreted in the urine after injection into a peripheral vein. These may be used to show the position, shape, size and outline of the kidneys or bladder. This is called an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) or excretory urogram. Iodine compounds can also be injected into the bladder or the kidneys from below, through the urethra and/or the ureters, and X-rays taken. Such X-ray studies of the kidneys are called retrograde pyelograms or retrograde urograms. Iodine compounds have in the past been injected into other body cavities such as the fluid-filled space around the spinal cord, and an X-ray called a myelogram may show some abnormality of the filling if a tumour is present. Nowadays myelograms have been replaced by CT or MRI studies.

Some iodine compounds are also excreted in bile into the gall bladder and bile ducts. X-rays can then be used to outline the shape and contents of the gall bladder (cholecystogram) and bile ducts (cholangiogram) that again may show abnormalities if tumours or other defects, such as gallstones, are present. Injection of contrast backwards up the biliary tree into the pancreatic duct is possible if a fine tube is passed into the ampulla of Vater in the duodenum (through which bile and pancreatic juice normally pass). This test is known as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP). It is endoscopic because passage of an endoscope through the mouth and down the oesophagus and stomach into the duodenum is necessary to insert the fine tube into the duodenal papilla.

7.3.3 Radiographic Screening

Whereas in years past all X-rays were recorded on a film as still photographs, nowadays techniques are used to allow the radiologist to study on a television screen the movement of a radio-opaque material (dye or contrast) such as barium or iodine in a body cavity. After a barium meal or barium enema, the patient is taken into a dark screening room where the radiologist can change the position of the patient to allow the radio-opaque material to flow into different parts of the organ being examined. This manoeuvring helps to visualise more accurately on the television screen the size, shape, position and outline of the organ under study and allows the radiologist to see, for example, if a lump in the bowel is faeces that can be moved or tumour attached to the bowel wall.

Air can be used to replace fluid in certain cavities and shows up as a dark shadow in X-rays. Air is sometimes used in the large bowel together with barium so that the barium coats onto the bowel wall and the air fills the bowel cavity. This allows X-rays to show more precisely the shape of the wall of the bowel and any lump projecting into the cavity of the bowel. This is called an air contrast barium enema and can be a very useful examination to detect tumours or polyps attached to the bowel wall. Air can also be used to replace some of the fluid in the cavities (ventricles) of the brain. This allows X-ray films to detect evidence of some brain lesions by the contrasting penetration of X-rays passing through air as compared to a tumour that might be distorting the shape of the brain ventricles. This study is known as an air encephalogram. This test was used much more often before CT and MRI scanning facilities became widely available.

In most cases, the X-ray density of a cancer is similar to the X-ray density of surrounding tissues and X-ray films alone are unlikely to show evidence of a deep-seated cancer. For cancers that are not so deep seated, however, such as breast cancer, X-ray (mammograms) can be used to detect any small differences in penetration of the tissues that may indicate the presence of a cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree