Each investigation may have distinct features. A general outline of steps is provided here, with the understanding that (1) each step may be more or less critical depending on the particular investigation, (2) steps may often occur simultaneously, and (3) investigations often have an iterative component that is a natural consequence of outbreak investigation.

Initial Stages of Investigation

Step 1. Ensure that any clinical or surveillance isolates that may be needed are stored for potential future use. Clinical and surveillance isolates obtained in the routine course of care are often discarded after a brief period of storage, and thus, involving the microbiology laboratory in the earliest stage of an investigation is important to ensure isolates that are still available are stored for possible future analysis.

Step 2. Notify appropriate leadership within the institution (ie, leadership of affected service lines, including physicians and nurses, microbiology, quality and safety, hospital administration), define the lead investigator (eg, designated infection preventionist paired with hospital epidemiologist), and assess resource needs (ie, data extraction, chart review, analytics, statistics, microbiological).

Step 3. Fact gathering. Perform preliminary literature review including search of outbreak databases,

11 institutional historical data, and confirmation if an outbreak is occurring or has occurred. Literature reviews can assist in guiding the current investigation as they highlight mechanisms of transmission and often provide lessons learned that can be applied to an active investigation.

Step 4. Develop a case definition, and apply it to relevant time frame to enable case finding and development of a line listing to enable chart review to identify potential common exposures and host factors. Cases may need to be subcategorized as confirmed, probable, and possible. Confirmed cases usually require laboratory confirmation. Probable cases usually have both typical clinical features and an epidemiological link. Possible cases have fewer clinical symptoms and weaker epidemiological links.

12Commonly included data elements are demographic variables, comorbidities, hospital locations, duration of hospitalization, invasive procedures, devices, medications and products administered, HCP or services involved in care, onset of infection, and details related to infection course. The relevant aspects of chart review should be determined in advance to the extent possible to minimize work effort of chart review and to allow for, when possible, electronic extraction of relevant fields. In many cases, it is useful for the investigative team to create a proposed line listing with variables of interest and to review them after having completed one or two chart reviews. At that time, additional fields may become relevant and be added so that chart review can be done as efficiently as possible on the remaining cases. When feasible, the use of electronic data extraction tools rather than manual review to increase data gathering efficiency and completeness should be employed. The mode of transmission (contact, droplet, airborne) should be considered when determining the parameters of the investigation as well as patient risk factors (ie, immunocompromised, nonimmune) and environmental risk factors (ie, common physical locations).

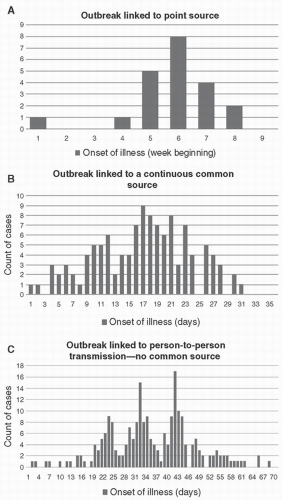

Step 5. With a case definition established, create an epidemiological curve plotting counts of cases over time, and conduct data analysis to present data in ways that can support hypothesis generation. In reality, epidemiological curves may not be needed if there are very few cases, but they can be useful to provide insights into the mechanism of transmission (

Fig. 9-1).

Step 6. Based on the available information to date, develop hypotheses to explain findings. In many cases, actions in the form of control measures will need to be taken before the studies to test these hypotheses are able to be conducted. For investigations involving a small number of cases, formal hypothesis testing is not needed or conducted. In these instances, based on the chart review and line-listing data, common links between cases may be readily identified and interventions implemented to end transmission. If an outbreak is larger than a few cases, if the common links are not readily apparent, or if transmission continues despite control measures, formal hypothesis testing with either case-control or retrospective cohort studies can help to identify the source of infection and risk factors. In case-control studies, the cases are defined by the case definition, and controls are identified through a retrospective review to identify at-risk but unaffected subjects. Such studies are generally straightforward to implement, however suffer from both selection and recall bias. Alternatively, a retrospective cohort study can be conducted in which subjects are identified by the exposure (ie, to a particular device) and then followed through some endpoint to determine whether or not the event/disease occurs. Retrospective cohort studies require that all controls can be identified which is usually true in hospitals and is the preferred design as it is less likely to have selection bias.

Step 7. Data analysis. This step begins earlier with the epidemiological curve but continues throughout the investigation. At any phase, control measures may be instituted

or modified, and revisions in case definition can result in having to revisit steps in the process.

Follow-up Stages of Investigation

At various time points in the investigation, updates in the case definition may occur, which may require revisiting the various steps outlined above. Ongoing surveillance may be required if not already being conducted, and at some point, a decision will need to be made regarding how long after the suspected end of transmission events such surveillance should continue. Periodic review of control measures for efficacy and continued need should take place. If transmission is ongoing in the face of implemented control measures, more drastic measures, such as ward closure, screening of HCP, and other interventions, may be required. Likewise, if transmission is ongoing and a specific physical space, device, or product is suspected but not confirmed, environmental or product sampling may be entertained. Prior to embarking on such sampling, several aspects need to be determined, including how sampling will be done (with preference for following a validated protocol); where samples will be analyzed as many clinical microbiology laboratories are not equipped to process nonclinical isolates; what will be the policy with respect to sequestration of devices or closing of physical spaces while isolates are being analyzed, if appropriate; and plans for remediation if environmental or product sampling identifies a potential source for the outbreak. Those leading an investigation in which such sampling is contemplated should be aware of these considerations before proceeding.