Key Points

- 1.

Primary carcinoma of the vagina comprises 3% of gynecologic malignancies.

- 2.

Metastatic disease to the vagina develops more commonly than primary disease.

- 3.

Most disease is treated with radiation therapy and in a similar fashion to cervical cancer.

The vagina, in sharp contrast to the uterine cervix and other gynecologic organs, rarely undergoes malignant transformation. Primary cancer of the vagina is uncommon, accounting for only 3% of gynecologic malignancies ( Table 9-1 ). Vaginal cancers in the United States occur in about 4000 women and account for 900 deaths each year.

| Series | Malignant Genital Neoplasms ( n ) | Vaginal Cancer (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Smith (1955) | 8199 | 1.5 |

| Ries and Ludwig (1962) | 14,785 | 2.1 |

| 6050 | 1.8 | |

| Wolff and Douyon (1964) | 4665 | 1.8 |

| 5715 | 1.2 | |

| Palumbo et al. (1969) | 2305 | 1.9 |

| Daw (1971) | 564 | 1.9 |

| Not given | 3.1 | |

| Manetta (1988) | 2149 | 1.3 |

| Eddy (1991) | 2929 | 3.1 |

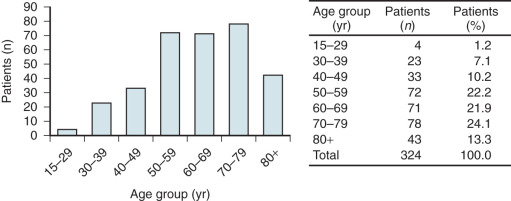

When primary vaginal cancer occurs, it is usually in the upper third of the vagina ( Table 9-2 ) and is most commonly an epithelial carcinoma. The mean age of diagnosis is approximately 65 years old with an incidence between 35 and 90 years and more than 50% of the cases occurring between the seventh and ninth decades of life ( Fig. 9.1 ). By convention, any primary malignant neoplasm involving both the cervix and vagina is classified as cervical cancer.

| Series | Upper Third | Middle Third | Lower Third |

|---|---|---|---|

| Livingstone (1950) | 34 | 4 | 42 |

| Bivens (1953) | 22 | 3 | 14 |

| Mobius (1956) | 89 | 0 | 29 |

| Arronet et al. (1960) | 14 | 8 | 3 |

| Whelton and Kottmeier (1962) | 20 | 13 | 19 |

| Blunt (1965) | 13 | 15 | 10 |

| Daw (1971) | 24 | 14 | 13 |

| Benedet (1984) | 46 | 3 | 19 |

| 22 | 8 | 16 | |

| 33 | 5 | 8 | |

| Total | 317 (56%) | 73 (13%) | 173 (31%) |

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent histologic subtype (78%). Adenocarcinoma (6%), melanoma (3%), and sarcoma (3%) have all been described as primary vaginal cancers ( Table 9-3 ). The relationship of diethylstilbestrol (DES) intrauterine exposure to clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina has resulted in the reporting of significant numbers of cases of vaginal adenocarcinoma in both exposed and unexposed individuals. A personal history of radiation therapy contributes to the development of vaginal sarcomas.

| Cell Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Squamous | 85 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 6 |

| Melanoma | 3 |

| Sarcoma | 3 |

| Miscellaneous | 3 |

The principal focus of this chapter is squamous cancers. Rare histologies are discussed later in the chapter. However, the clinical evaluation and staging for vaginal tumors are the same for all types of vaginal cancers.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vagina

Epidemiology

Similar to cervical cancer, epidemiologic evidence suggests that vaginal cancer has a strong relationship with human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. HPV subtype 16 presence has been associated with up to two-thirds of all new cases of vaginal cancer. Approximately one-third of women who develop vaginal cancer will have a history of cervical dysplasia or cervical cancer more than 5 years earlier. A study from the University of South Carolina found that the median interval between cervical disease and development of vaginal cancer was 14 years, and 16% of patients had a history of prior radiation. Proposed mechanisms for developing vaginal cancer with a remote history of cervical cancer include occult residual disease, radiation-induced tumorigenesis, and a new primary cancer in a high-risk individual. A large retrospective cohort of more than 130,000 women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (CIN3) demonstrated a significantly increased risk of vaginal cancer compared with women within the same population and time period (incidence ratio, 6.8). Similarly, of the 153 women treated for vaginal cancer, 34 had a prior history of cervical cancer. In general, a new vaginal lesion 5 years or more after treatment of cervical cancer constitutes a new primary vaginal cancer.

The natural course of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is not well understood because most patients are treated after they are diagnosed. Up to 99% of VAIN 1 and 93% of VAIN 2/3 result from HPV, with HPV-16 subtype being the most common. Thus, risk factors for vaginal cancer are similar to those for cervical neoplasia: multiple lifetime sexual partners, early age at first intercourse, and smoking. Between 3% and 7% of cases of VAIN progress to invasive carcinoma despite treatment. Chronic vaginal irritation has been suggested to contribute to the etiology of vaginal cancer; however, the mechanism by which this promotes carcinogenesis is not well understood and has not been extensively studied.

Screening

The diagnosis of vaginal cancer may often be missed in women who have had a prior hysterectomy. It is particularly important that the lateral “horns” of the upper vaginal vault be thoroughly examined. For some patients, this may require use of an endocervical speculum to ensure a complete evaluation of the vaginal apices.

The Papanicolaou (Pap) test is effective in detecting vaginal cancer in asymptomatic women. The American Cancer Society recommends that Pap screening for cervical cancer may be discontinued in women who have had a hysterectomy for conditions other than cervical dysplasia or cancer. However, women with a history of cervical dysplasia or cervical cancer are at increased risk, and Pap testing should be continued whether or not they may have had a hysterectomy.

For a screening test to be effective, the incidence of the disease must be sufficient to justify the cost. Because the incidence of vaginal cancer is so low, routine screening is not cost effective. However, development of vaginal cancer is possible even in women with a history of hysterectomy for benign disease. Bell and colleagues described 87 patients with primary cancer of the vagina, 31 of whom had undergone total hysterectomy for benign disease. Benedet and colleagues found that 19 of their 97 patients (20%) with vaginal cancer had surgery for benign diseases. Peters et al. reported that 38% (25 of 68) of the patients in their series had undergone prior hysterectomies for benign disease. Guidelines aside, these observations underscore the need to individualize vaginal cancer cytologic screening by careful consideration of estimated risks and benefits of such clinical activity.

Signs and Symptoms

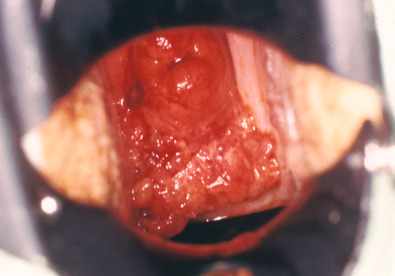

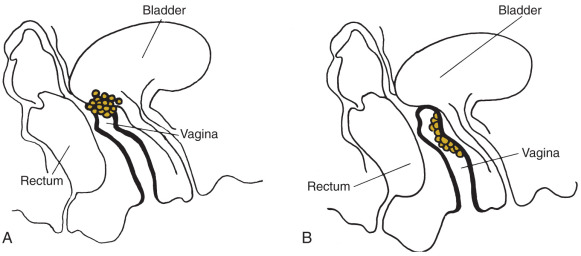

The signs and symptoms of invasive vaginal cancer ( Fig. 9.2 ) are similar to those of cervical cancer. Many women may be asymptomatic. Painless vaginal discharge, often bloody, is the most frequent symptom in most series. Postcoital or postmenopausal vaginal bleeding is the initial symptom in many patients with invasive lesions, and a gross lesion is obvious on speculum examination. Patients may also present with watery, blood-tinged, or malodorous vaginal discharge. Urinary symptoms (pain and frequency) are more common than with cervical cancer because neoplasms that are lower in the vagina are close to the vesicle neck, with resulting compression of the bladder at an earlier stage of the disease. Tenesmus is commonly associated with posterior vaginal lesions. Approximately 5% to 10% of women are asymptomatic, with disease diagnosed on suspected physical examination and confirmed by biopsy.

Diagnostic Considerations

All patients presenting with a vaginal cancer need a full workup to rule out metastatic disease. Medical history should emphasize history of cancer, radiotherapy, and surgery. Physical examination, including an adequate pelvic examination (under anesthesia if necessary), should be performed. The diagnosis is often missed on first examination, especially if the lesion is small and covered by the blades of the speculum. Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic confirmation on biopsy.

In patients with an abnormal Pap test result and no gross abnormality, careful vaginal colposcopy is necessary. To differentiate between an early vaginal cancer and VAIN III, it is often necessary to perform a partial upper vaginectomy as reapproximated vaginal tissue at the time of hysterectomy may bury the lesion.

Hoffman and associates reported on 32 patients with VAIN III who underwent an upper vaginectomy; 28% had invasive carcinoma.

Metastatic carcinoma to the vagina occurs more often than primary disease because more than 80% of malignant vaginal lesions are metastasis from other sites. In 269 patients with metastatic vaginal cancer, Mazur et al. found that 84% were from genital sites, and the remaining 16% were most commonly metastatic from the gastrointestinal tract or breast. The cervix (32%) and endometrium (18%) are the most common primary sites of cancer. Whereas endometrial carcinomas and choriocarcinomas often metastasize to the vagina, rectal and bladder cancers directly invade the vagina.

When the primary site of growth is in the vagina and does not involve surrounding organs (eg, vulva or cervix), the tumor is considered a primary vaginal cancer. Special consideration needs to be made for patients with a remote (>5 years) or questionable history of a gynecologic malignancy (especially cervical cancer) who present with a vaginal lesion. Patients with a history of endometrial cancer and a vaginal lesion with a histologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma consistent with recurrence are diagnosed with recurrent endometrial cancer.

After being diagnosed with vagina cancer, patients should be examined for evidence of local or distant spread in a manner analogous to that of cervical cancer. All patients should have at least the following diagnostic studies in addition to a thorough history and physical examination: chest radiography, intravenous pyelography, cystoscopy, and proctosigmoidoscopy, the last two depending on the location of disease. A computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can replace the pyelography, cystoscopy, and proctosigmoidoscopy. If bone pain is present, further radiographs are warranted. Although staging is clinical, not surgical, an imaging evaluation should be performed to evaluate lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and the genitourinary system.

Staging

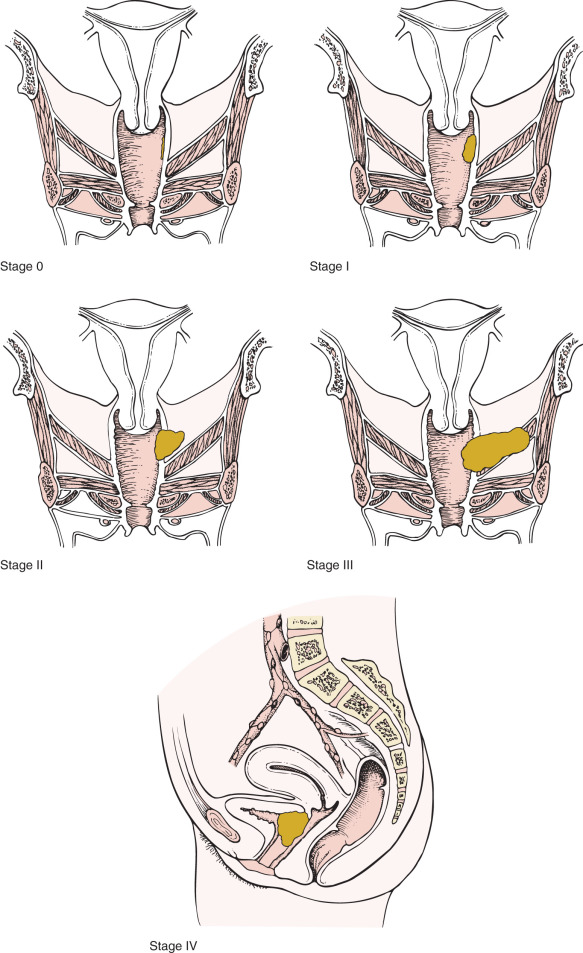

Most vaginal cancers are staged using the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) combined with the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system ( Fig. 9.3 ); a summary of the staging classification last updated January 2010 follows:

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinoma |

| Stage I | Carcinoma is limited to the vaginal wall |

| Stage II | Carcinoma has involved the subvaginal tissue but has not extended onto the pelvic wall |

| Stage III | Carcinoma has extended onto the pelvic wall |

| Stage IV | Carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved the mucosa of the bladder or rectum; bullous edema or tumor bulge into the bladder or rectum is not acceptable evidence of invasion of these organs |

| Stage IVa | Spread of the growth to adjacent organs or direct extension beyond the true pelvis |

| Stage IVb | Spread to distant organs |

Vaginal cancer is staged clinically. By the FIGO system, tumors that involve the cervix or vulva are not considered primary vaginal cancers and are classified as either cervical or vulvar primaries. Although FIGO does not specify the stage of patients with inguinal lymph node involvement, the AJCC assigns patients with T1 to T3 tumors with positive inguinal lymph nodes to stage III. Involvement of the pubic symphysis is also classified as stage III. Similar to cervical cancer staging, FIGO does encourage the use of advanced imaging modalities to guide therapy.

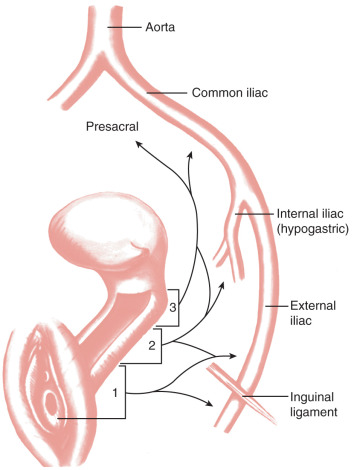

Patterns of Spread

Vaginal cancer metastasizes by direct extension, lymphatic dissemination, and hematogenous spread. The pelvic soft tissues, pelvic bones, bladder, and rectum are commonly involved via direct extension in patients with locally advanced disease. The lymphatic vasculature of the vagina begins as an extremely fine capillary meshwork in the mucosa and submucosa ( Fig. 9.4 ). In the deep layers of the submucosa and muscularis, there is a similar parallel but coarser network. Irregular anastomoses have been demonstrated between the two. Both systems drain into small trunks that coalesce at the lateral aspect of the vagina and form a number of collecting trunks. It is at this point that the efferent lymph drainage channels of the organ originate. The lymphatic trunks of the upper vagina drain into the iliac and eventually the paraaortic lymph nodes. A lymphatic network that anastomoses with the regional lymph nodes of the femoral triangle principally drains the lower vagina. All lymph nodes in the pelvis may at one time or another serve as primary sites or regional drainage nodes for vaginal lymph and its contents.

Because most patients with vaginal cancer are treated with radiation, the incidence of lymph node involvement is not well recorded. However, retrospective studies demonstrate that 30% to 35% of patients with vaginal cancer have lymph node metastasis. Paraaortic spread is almost exclusively seen in patients with concomitant pelvic node metastases.

Imaging and Vaginal Cancer

Imaging such as CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET) are often used to guide therapy. MRI is particularly useful in delineating tumor size and extent of spread to the paravaginal or parametrial involvement given its superior soft tissue resolution. PET imaging has become a standard diagnostic tool in the initial staging of cervical cancer and for posttreatment surveillance and has similar applicability for vaginal cancer. Metabolic imaging with PET has been shown to be more sensitive than CT and MRI, specifically for cancer of the head and neck, lung, esophagus, and cervix. In a study from Washington University, Lamoreaux and associates found that PET imaging detected primary and metastatic lesions more often than CT scans. In vaginal cancers, PET is more sensitive for detecting primary vaginal tumors and involved inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes. We recommend that all patients with vaginal cancer have imaging, and PET/CT with or without pelvic MRI is a reasonable option for these patients.

Sentinel Lymph Node Dissection

Patients with vaginal cancer rarely undergo lymph node dissection. Sentinel lymph node evaluation is a technique to determine if there is microscopic nodal metastasis. Frumovitz and colleagues evaluated the utility of radiocolloid and blue dye injection in 14 women with newly diagnosed vaginal cancer. The authors found that lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor does not always follow the predicted lymphatic channels. Pretreatment lymphoscintigraphy did improve treatment planning in this small study. However, because of the lack of data, incorporation of sentinel lymph node dissection into the treatment plan should be limited to research protocols.

Prognostic Features

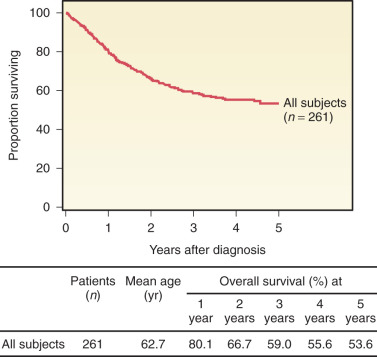

Our understanding of vaginal cancer and improved radiation techniques have increased survival rates ( Fig. 9.5 and Table 9-4 ). Several investigators believe that age at time of diagnosis is one of the most important prognostic factors. Reflecting intolerance of aggressive multimodality therapy and attendant comorbidities, age acts as a surrogate of clinical outcome. Although not well described, performance status likely reflects a factor with greater precision in determining the impact of chronologic age. Tumor histology may also have prognostic relevance. Vaginal melanomas and sarcomas have the poorest prognosis compared with SCC and adenocarcinomas. However, survival differences among the different histologies have not been well documented due to rarity of cases.

| Authors | Cases ( n ) | STAGE AND SURVIVAL (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | All Stages | ||

| Krepart (1978) | 14 * | 65 | 60 | 35 | 39 | 51.8 |

| 36 * | 71 | 66 | 33 | 0 | 42.8 | |

| 105 * | 81 | 42 | 30 | 9 | 50.8 | |

| 80 * | 78 | 57 | 39 | 0 | 8.8 | |

| 27 * | 100 | 75 | 22 | 0 | 56.8 | |

| 75 * | 71 | 50 | 15 | 0 | 45.8 | |

| Reuben et al. (1985) | 68 * | 79 | 52 | 54 | 0 | 49.8 |

| 28 * | 100 | 50 | 0 | 25 | 42.8 | |

| Eddy (1991) | 84 * | 70 | 45 | 35 | 28 | 50.8 |

| 100 * | 67 | 53 | 0 | 15 | 46.8 | |

| 792 * | 73 | 58 | 58 | 58 | ||

Stage, tumor location, and tumor size also appear to affect prognosis. In a review of 843 patients with vaginal cancer, patients with stage I disease had a 64% to 90% 5-year survival rate; rates were 31% to 80% for stage II, 0% to 79% for stage III, and 0% to 62% for stage IV. In this study, lesions of the distal vagina had a poorer prognosis than those originating in the proximal vagina. In a review of 104 patients, found 6.8% survivors among 29 patients with cancer of the lower third of the vagina, 25% of 48 patients with tumors of the middle third, and 37% of 27 patients with lesions of the upper third. In 1958, Merrill and Bender reported a 29% survival rate in 14 patients with upper third lesions and an 11% rate in nine patients with distal third involvement. More recently, reported better survival for patients with lesions smaller than 3 cm compared with those larger than 3 cm. Chyle et al. found that tumor size larger than 5 cm was associated with a higher local recurrence rate compared with smaller tumors.

In 2005, Frank and colleagues at MD Anderson Cancer Center reported their 30-year experience treating patients with vaginal cancer. In this series of 193 patients, disease-specific survival and pelvic disease control rates were correlated with stage (I, II, or III/IV) and tumor size (<4 cm or >4 cm).

Intuitively, lymph node status at the time of diagnosis would portend a worse prognosis; however, this has not been well evaluated. In one study by Pingley et al., the 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement was 56% compared with 33% for patients with lymph node involvement. Furthermore, as in radiation therapy trials of cervical cancer patients, time to treatment initiation and total treatment time also affect vaginal cancer survival. Lee and associates found that the pelvic control rate was 97% if the treatment was completed within 63 days compared with 54% if treatment lasted longer than this time.

In a review of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) population-based cancer registry, 2149 women with vaginal cancer between 1990 and 2004 were identified. Advanced stage, tumor size larger than 4 cm, aggressive histologies (eg, melanoma), and combined treatment modality (vs. surgery alone) were associated with a worse prognosis.

Management

Until the 1930s, vaginal cancers were considered incurable. With advances in radiation therapy, cure rates for even advanced cancers approach those for cervical cancer. Early stage vaginal cancers (stages I and II) treatment approaches include surgical resection or definitive radiotherapy. Bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy is required given the high risk of occult nodal spread. Surgical series have reported rates of pathologic nodal involvement for stage I of 6% to 14% with stage II of 26% to 32%. Advanced-stage vaginal cancers are mainly managed with definitive radiation therapy. The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced vaginal cancers has only been reported as case reports and small series with most patients relapsing and dying of disease. Consideration for up front exenteration may also be considered in carefully selected patients with resectable advanced-stage disease.

Prevention

Although the potential effect of HPV vaccines may not be as high for vaginal cancer as it may be for cervical cancer, vaccinating young women against HPV, specifically types 16 and 18, should help to reduce the incidence of HPV-related vaginal disease.

Stage 0 and I

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia usually occurs at the vaginal apex, is multifocal, and is common in patients with a history of cervical dysplasia. Treatment options for patients with VAIN include surgery (wide local excision or vaginectomy), 5% fluorouracil cream, local ablation (eg, laser, cryotherapy, electrodiathermy), and intracavitary radiation ( Table 9-5 ).

| Stage | External Irradiation | Vaginal Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Surgical excision preferred for localized disease | 7000-cGy surface dose |

| I | ||

| 1- to 2-cm lesion | Brachytherapy irradiation, 6000–7000 cGy * | |

| Larger lesions | 4000–5000 cGy of the whole pelvis | Brachytherapy delivering 3000–4000 cGy |

| II | 4000–5000 cGy of the whole pelvis | Same as for stage I |

| III | 5000 cGy of the whole pelvis (optional 1000–2000 cGy through reduced fields) | Brachytherapy implant, 2000–3000 cGy (if tumor regression is satisfactory) |

| IV (pelvis only) | Same as for stage III | Same as for stage III |

* Surgical excision for selected sites on 1- to 2-cm lesions may be used instead of brachytherapy.

Creasman and associates reported the results of the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), a large central registry of hospital data, for 10 years (1984–1994). There were 4885 cases, with 1242 carcinomas in situ (CIS) representing 26% of all vaginal lesions. CIS was almost exclusively treated with surgery; only 5% were treated with radiotherapy. Brown and colleagues reported no new cases of in situ or invasive carcinoma of the vagina developing after radiation therapy for CIS or early invasive carcinoma. Their report discouraged overly aggressive therapy for early-stage tumors because of the good prognosis for these lesions and the adverse effects of high-dose irradiation on the pliability of the vagina and on sexual function. Lee and Symmonds reported the results of 66 patients treated previously with wide local excision or partial vaginectomy and seven patients with multicentric disease treated with total vaginectomy. Only one patient developed recurrence; recurrence was vaginal carcinoma, which resulted in the patient dying of disease. In young, sexually active patients with diffuse involvement of the vaginal epithelium, total or subtotal vaginectomy with split-thickness skin graft reconstruction of the vagina often allows for excellent long-term results. When radiation therapy is chosen, patients who have CIS and superficial stage I tumors can be treated with intracavitary insertion alone.

Surgical management is an option for lesions 0.5 cm or less in patients with invasive carcinoma. For early lesions, particularly in the upper vagina (see Fig. 9.2 ), surgery may be preferred in many patients. Peters et al. have described superficially invasive SCC of the vagina as a lesion that invades less than 2.5 mm from the surface, lacking involvement of lymphovascular spaces, and occurring in a background of CIS. Their experience with six patients suggests that local therapy was sufficient, and no attempt was made to treat pelvic nodes either surgically or with irradiation. This conservative approach might allow preservation of optimal sexual function in young patients who have these early invasive SCC and adenocarcinoma lesions.

There are no randomized trials defining treatment exclusively for vaginal cancer because of its rarity. Treatment approaches have been largely extrapolated from cervical and anal cancers. For invasive carcinoma thicker than 0.5 cm, total vaginectomy and lymphadenectomy have been performed in the past. If the patient did not have a prior hysterectomy, a radical hysterectomy and upper vaginectomy would need to be performed. However, pelvic external-beam radiotherapy and interstitial implants may be appropriate for some patients, especially those with tumors larger than 2 cm and those involving the mid to lower portion of the vagina. Patients with small stage I cancers (<2 cm) who are not good surgical candidates can adequately be treated with brachytherapy alone. For large vaginal tumors (>2 cm), options for radiating the primary lesion are tailored by physician preference and extent of disease. Bulky stage I cancers (>2 cm) of the upper portion of the vagina in patients with intact uteri are treated with techniques similar to those used for carcinoma of the cervix. External irradiation in a dose of 4500 to 5000 cGy is generally recommended with another 2500 cGy given as intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy in bulky stage I and stage II cancers (see Table 9-5 ). For young patients who require radiation therapy, pretreatment laparotomy or laparoscopy with ovarian transposition and surgical staging is a rational approach.

Stage II to IVa

For patients who have stage II to IV vaginal cancer, treatment is tailored to the extent of the disease, and the radiation therapy plan should reflect consideration of the depth of invasion of the lesion. Proper planning of radiation therapy and individualization of treatment plans are essential to minimize the more serious complications of acute and long-term radiation sequelae in these organs. The difficulty in applying radiation systems to vaginal cancer led some, such as Wertheim and Brunschwig, to advocate for radical exenteration surgery as primary therapy. However, the complications associated with this radical procedure, especially in older patients, have become a serious limiting factor to surgical approach.

Patients with advanced-stage disease should be treated with external irradiation and brachytherapy. External irradiation to the pelvis is usually sufficient, and paraaortic extension is not routinely administered. Groin radiation is often considered if the tumor involves the lower third of the vagina or in the presence of metastatic groin disease. Perez and associates evaluated 149 patients with vaginal carcinoma and clinically negative lymph nodes who were not treated with groin radiation. In the group of patients with tumors confined to the upper vagina, there were no recurrences compared with an 8% recurrence rate in those patients whose tumor involved the lower third of the vagina.

If the uterus is intact and the lesion is in the upper vagina, an intrauterine tandem and ovoids would be appropriate. If the patient has had a hysterectomy, interstitial radiation alone or in combination with intracavitary therapy optimizes dose distribution.

For patients who can be treated with brachytherapy only, a minimum of 6000 to 7000 cGy is delivered to the neoplasm in 5 to 7 days. Pelvic and groin radiation consists of a total of 45 to 50.4 Gy given in 1.8-Gy fractions daily. Use of concomitant sensitizing chemotherapy is discussed in the following section.

If there is metastatic lymph node involvement to the pelvic or groin lymph nodes, external radiation is given to a dose of 60 to 66 Gy. In addition, adenopathy greater than 2 cm may be best controlled with excision. The deep nodes must be included in the treatment fields because large tumors have a high incidence of regional lymphatic metastasis. After receiving 5000 cGy, the patient with a large lesion should be reevaluated for an additional 1000 to 2000 cGy of external radiation to reduced field. Higher radiation doses, however, are associated with greater vaginal toxicity. Newer treatment planning protocols using intensity-modulated radiation therapy may yield higher tumor control with less local normal tissue effects. Long-term morbidity outcomes with this technology are awaited.

Radiation therapy alone for locally advanced vaginal cancers generate relatively poor outcomes because of predominantly local failures. Chemoradiation is standard of care for patients with locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Because the natural history, histology, and risk factors are similar for vaginal cancer, chemosensitization with weekly cisplatin has been recommended in patients receiving radiation for advanced-stage disease. Prospective studies will likely not be performed given the rarity of this disease. There are several small retrospective series that demonstrated high locoregional control rates after chemoradiation therapy with no increase in radiation-related long-term side effects compared to radiation alone. A single institution series of 71 patients treated with definitive radiation therapy with ( n = 20) or without ( n = 51) concurrent chemotherapy, the addition of chemosensitization resulted in improvement in 3-year disease-free survival (43 vs. 73%) and 3-year overall survival (56 vs. 79%). However, given the lack of high-quality data, radiation therapy alone is reasonable if the patient is not a candidate for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. A phase III clinical trial of ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor triapine is currently being conducted by the NRG-GOG (Gynecologic Oncology Group) in women with stage IB2, II, or IIIB-IVA or stage II-IVA vaginal cancer (NCT02466971). Women with advanced-stage vaginal cancer are eligible.

Chemotherapy

Studies are limited regarding the experience with chemotherapy for patients with vaginal cancer. In a phase II GOG study, 26 patients with progressive or recurrent vaginal carcinoma were treated with cisplatin (50 mg/m 2 every 3 weeks). There was minimal, insignificant activity, particularly in the patients with SCC. Other agents that have been used for the treatment of vaginal cancer include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), mitomycin-C, epirubicin, or combinations of two of these agents.

A small series of patients with stage II vaginal carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery has been reported by Panici and colleagues. Eleven patients were treated with paclitaxel 175 mg/m 2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m 2 for three courses followed by surgery. There were a 27% complete response rate and a 64% partial response rate. At a median follow-up of 75 months, two (18%) patients had a recurrence, and one died of disease.

Special Considerations

Although one is often dealing with a radiosensitive neoplasm in a relatively radioresistant bed (the vagina), serious limitations exist. The proximity of relatively radiosensitive normal tissues, such as the bladder and rectum, provides a challenge to the therapist, especially in the treatment of tumors in the lower third of the vagina. Therapy must be individualized, and radical surgery should be reserved for treatment failures ( Fig. 9.6 ).

The incidence of complications after radiation therapy or surgery for vaginal cancer can be substantial. Serious complications consist primarily of rectal stenosis, rectovaginal fistulas, and severe rectal bleeding often requiring diversion. As many as 35% of patients experience cystitis or proctitis during or shortly after therapy, but symptoms usually resolve spontaneously. A few patients have extensive vaginal necrosis that usually resolves with prolonged conservative management.

Frank and associates found that the incidence of major complications associated with radiation were associated with FIGO stage. Four percent of stage I patients, 9% of stage II patients, and 21% of stage III/IVa patients had major complications. Patients who are sexually active should be encouraged to continue regular intercourse. For others, vaginal dilators should be used to maintain vaginal patency during and after therapy.

Survival and Recurrence

A study by Rutledge in 1967 reported 3- and 5-year survival rates of 42% and 44%, respectively, for patients treated primarily with radiotherapy. Comparable survival results at 5 years were reported by Prempree and colleagues, who used radiotherapy for stage I (83%), stage II (63%), stage III (40%), and stage IV (0%) lesions; their absolute 5-year cure rate for all stages was 55.5%.

In 1982, Perez and Camel reported their long-term follow-up of patients treated with radiation therapy for invasive carcinoma of the vagina. The actuarial disease-free 5-year survival rates for stage I (39 patients) were 90%; stage IIa (39 patients), 58%; stage IIb (21 patients), 32%; stage III (12 patients), 40%; and stage IV (8 patients), 0%. Of 39 patients with stage I carcinoma, 37 (95%) showed no evidence of vaginal or pelvic recurrence. Most of them received interstitial or intracavitary therapy or both; the addition of external-beam irradiation did not significantly increase survival or tumor control. In stage IIa (paravaginal extension), tumor was controlled in 22 of 34 patients (64.7%) with a combination of brachytherapy and external-beam irradiation; only two of five (40%) treated with brachytherapy alone exhibited tumor control in the pelvis. The incidence of complications was 9.7% for all stages.

In 1991, Eddy and coworkers published similar results for stage I and stage II lesions of the vagina treated with curative radiotherapy and reported 5-year survival rates of 78% for patients assigned to stage I and 71% for patients assigned to stage II. In addition, reported local control rates of 72% for stage I and 62% for stage II disease ( Table 9-6 ). In the large database (NCDB) reported in 1998, the 5-year relative survival rates were 96% for stage 0, 73% for stage I, 58% for stage II, and 36% for stage III and IV. Women with stage I disease who were treated with surgery had a 5-year survival rate of 90% compared with 63% for patients treated with radiotherapy and 79% for patients treated with surgery and radiotherapy.