Invasive Breast Cancer

Invasive breast cancers constitute a heterogeneous group of lesions. The vast majority are adenocarcinomas; their histopathologic classification is based upon the growth pattern and cytologic features of the tumor. Although the most common types are designated “ductal” and “lobular,” this distinction is not meant to indicate the site of origin within the mammary ductal system. Most invasive breast cancers arise in the terminal duct lobular unit, regardless of histologic type.1

Mammographic screening has had a dramatic impact on the nature of invasive breast cancers encountered in clinical practice. Mammography results not only in the detection of smaller invasive breast cancers and fewer cancers with axillary lymph node involvement but also in more special type cancers (particularly tubular carcinomas) and cancers of lower histological grade.2, 3 and 4

At the present time, histopathology remains the basis for the classification of invasive breast cancers. However, knowledge gained from molecular studies will likely result in modification of the existing histopathologic classification system. Several molecular subtypes of breast cancer identified through gene expression profiling studies have been recognized for over a decade. Most notable among these are the luminal A, luminal B, HER2, and basal-like types.5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 Other molecular subtypes identified in at least some studies include normal breast-like, molecular apocrine, and claudin-low groups (see subsequent text).9,10 Given that

clinicians are thinking increasingly in terms of these molecular subtypes in formulating treatment recommendations,11 pathologists must become familiar with this terminology. Therefore, molecular subtypes will be mentioned briefly in the subsequent discussion of histologic types of breast cancer where appropriate; these will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

INVASIVE DUCTAL CARCINOMA (INVASIVE CARCINOMA OF NO SPECIAL TYPE)

Invasive ductal carcinomas are the most common type of invasive breast cancer, accounting for up to 70% to 75% of the cases in some series. These tumors comprise a heterogeneous group with regard to pathologic features and clinical course and are characterized histologically by the lack of sufficient features to warrant categorization as any of the special type tumors. For this reason, the WHO classification designates these tumors as invasive carcinomas of no special type.12

Clinical Presentation

Invasive ductal carcinomas usually present as a palpable tumor and/or mammographic abnormality; the latter is most often a spiculated mass with or without associated microcalcifications.

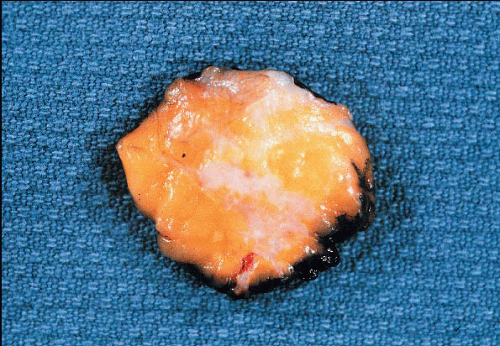

Gross Pathology

The classical macroscopic appearance of invasive ductal carcinoma is that of a scirrhous carcinoma, characterized by a firm, sometimes rockhard mass, which on a cut section has a gray-white to tan, gritty surface (Fig. 10.1). This consistency and appearance is due to the desmoplastic tumor stroma and not the neoplastic cells themselves. Invasive ductal carcinomas composed primarily of tumor cells with little desmoplastic stromal reaction are grossly tan and soft. Although most invasive ductal cancers have a stellate or spiculated contour with irregular peripheral margins, some are grossly well circumscribed.

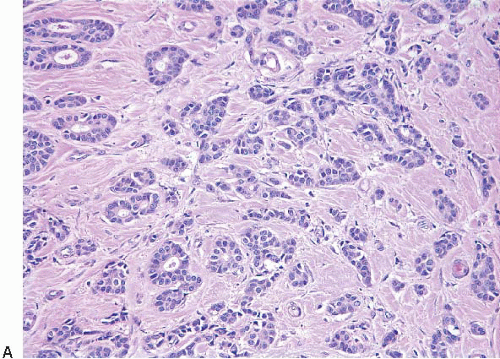

Histopathology

The microscopic appearance of invasive ductal carcinomas is highly heterogeneous with regard to growth pattern, cytologic features, mitotic activity, stromal desmoplasia, and extent of associated ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Variability in histologic features may be seen within a single case. The tumor cells may be arranged as well-formed glandular structures; as nests, cords, or trabeculae of various sizes; or as solid sheets. Foci of necrosis are evident in some cases and may be extensive. Cytologically, the tumor cells range from those that show little deviation from normal breast epithelial cells to those exhibiting marked cellular pleomorphism and nuclear atypia. Mitotic activity can range from undetectable to brisk. The degree of gland formation, nuclear atypia, and mitotic activity are considered together in determining the combined histologic grade, an important prognostic factor (see the Prognostic Factors section) (Fig. 10.2, e-Fig. 10.1). Stromal desmoplasia is inapparent to minimal in some cases. At the other end of the spectrum, some tumors show such prominent stromal desmoplasia that the tumor cells constitute only a minor component of the lesion. Similarly, some invasive ductal carcinomas have no identifiable component of DCIS, whereas in others, the DCIS is the predominant component of the tumor. Associated stromal lymphoid or lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates range from absent to so marked that they obscure the tumor cells. Finally, the microscopic border of these cancers may be infiltrating, pushing, circumscribed, or mixed.

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Although the expression of innumerable biomarkers has been studied in invasive breast cancers over the last several decades, at the present time, only three are universally used in daily practice: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2. The expression of these markers is highly variable in invasive ductal carcinomas, as might be anticipated from their histologic heterogeneity. In most contemporary series, approximately

70% to 80% of invasive ductal carcinomas are ER positive and 10% to 15% show HER2 protein overexpression and gene amplification. Invasive ductal carcinomas characteristically show cell membrane expression of E-cadherin, although the level of expression may be reduced in some cases.13 Given their histologic heterogeneity, it should not be surprising that invasive ductal carcinomas exhibit a wide spectrum of genetic/genomic alterations as well as heterogeneity with regard to molecular subtypes as defined by gene expression profiling.14

70% to 80% of invasive ductal carcinomas are ER positive and 10% to 15% show HER2 protein overexpression and gene amplification. Invasive ductal carcinomas characteristically show cell membrane expression of E-cadherin, although the level of expression may be reduced in some cases.13 Given their histologic heterogeneity, it should not be surprising that invasive ductal carcinomas exhibit a wide spectrum of genetic/genomic alterations as well as heterogeneity with regard to molecular subtypes as defined by gene expression profiling.14

Clinical Course and Prognosis

The prognosis is highly variable in this heterogeneous group of tumors and is related to a variety of factors including lymph node status, tumor size, histologic grade, and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (see the Prognostic and Predictive Factors section).

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma is one of exclusion; as noted above, these tumors lack sufficient histologic features to qualify for categorization as any of the special type tumors described later.

INVASIVE LOBULAR CARCINOMA

Invasive lobular carcinomas account for approximately 5% to

15% of invasive breast carcinomas and are the second most common type.15 The variation in incidence is related at least in part to differences in diagnostic criteria in different studies. In addition, the increase in frequency of invasive lobular carcinomas in more recent series may be related to the use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy.16

Invasive lobular carcinomas are characterized by multifocality in the ipsilateral breast and appear to be more often bilateral than other types of invasive breast cancer (reported range of bilaterality 6% to 47%). However, some studies have shown the incidence of subsequent contralateral breast cancer among patients with invasive lobular carcinoma to be similar to that of patients with invasive ductal carcinoma.17, 18 and 19

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) coexists with invasive lobular carcinoma in 70% to 80% of the cases.17,20,21

Clinical Presentation

Invasive lobular carcinoma may present as a palpable mass or as a mammographic abnormality, with characteristics similar to those of invasive ductal carcinomas. However, both the findings on physical examination and the mammographic appearance of invasive lobular carcinomas may be quite subtle. On physical examination, there may be only a vague area of thickening or induration without definable margins. Mammographic findings may be equally subtle, with many invasive lobular carcinomas appearing as poorly defined areas of asymmetric density with architectural

distortion and others revealing no mammographic abnormalities, even in the presence of a palpable mass. In fact, the extent of the tumor may be substantially underestimated by both physical examination and mammography. While the use of magnetic resonance imaging has been advocated to more clearly define the lesion extent in patients with invasive lobular carcinoma, the high sensitivity and low specificity of this technique may result in overestimation of tumor size in some cases.22

distortion and others revealing no mammographic abnormalities, even in the presence of a palpable mass. In fact, the extent of the tumor may be substantially underestimated by both physical examination and mammography. While the use of magnetic resonance imaging has been advocated to more clearly define the lesion extent in patients with invasive lobular carcinoma, the high sensitivity and low specificity of this technique may result in overestimation of tumor size in some cases.22

Gross Pathology

Some invasive lobular carcinomas appear as firm, gritty, gray-white masses, indistinguishable from invasive ductal carcinomas. However, in other cases, no mass is grossly evident and the breast tissue may have only a rubbery consistency. In still other cases, no abnormality is evident on visual inspection or upon palpation of the involved breast tissue and the presence of carcinoma is revealed only upon microscopic examination.23

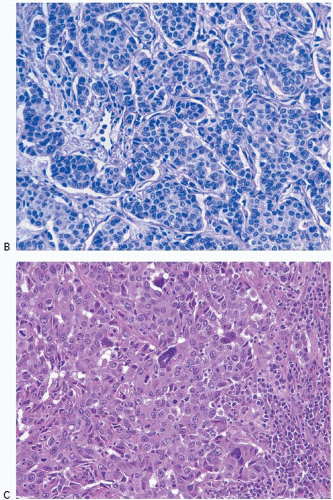

Histopathology

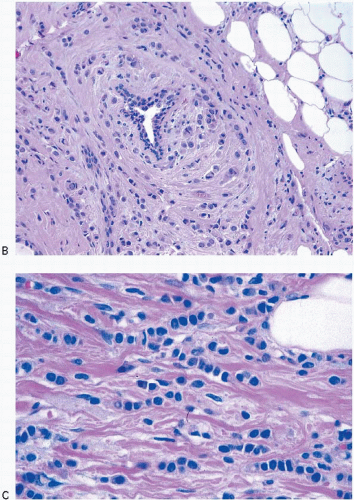

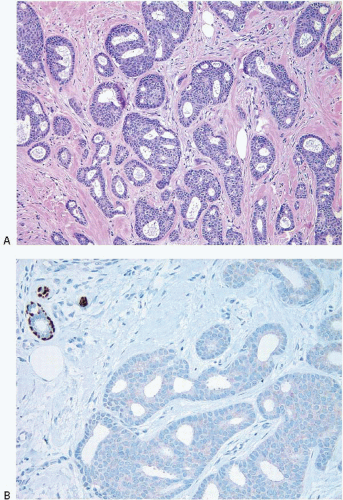

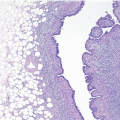

Invasive lobular carcinomas as a group show distinctive cytologic features and patterns of tumor cell infiltration of the stroma. The classical form is characterized by small, relatively uniform neoplastic cells that invade the stroma singly and in a single-file pattern, which results in the formation of linear strands.24 These cells frequently encircle mammary ducts in a concentric pattern (Fig. 10.3, e-Fig. 10.2). Furthermore, the tumor cells may infiltrate the breast stroma and adipose tissue in an insidious fashion, invoking little or no desmoplastic stromal reaction and with little disruption of the background architecture. The nuclei of the neoplastic cells are usually small, show little variation in size, and are often eccentric. Mitotic figures are infrequent. The cells often contain intracytoplasmic lumina, which may contain an eosinophilic globule. In some cells, these lumina may be large enough to impart a signet ring cell appearance. However, in the classical form of invasive lobular carcinoma, cells with a signet ring configuration comprise only a small proportion of the tumor cell population.

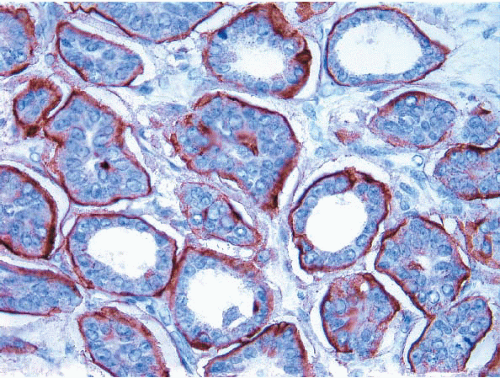

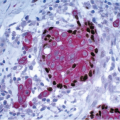

Many examples of invasive lobular carcinoma (as well as LCIS) are characterized histologically by tumor cells that are loosely cohesive. The molecular basis for this feature is the loss of expression of E-cadherin on the tumor cell membranes, which, in turn, is due to the combination of loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 16q22.1 (the region of the E-cadherin gene) accompanied by mutations in the gene encoding this protein or silencing of gene expression by promoter methylation (Fig. 10.4). Loss of E-cadherin expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) may be a helpful adjunct in distinguishing lobular from ductal-type carcinomas in problematic cases.25, 26, 27, 28 and 29 However, approximately 15% of invasive lobular carcinomas exhibit E-cadherin expression (Fig. 10.5).30,31 Therefore, an invasive breast carcinoma that has the histologic features of an invasive lobular carcinoma but is E-cadherin positive should not be classified as an invasive ductal carcinoma. The expression of E-cadherin in such cases is considered to be aberrant and is often accompanied by abnormalities in expression of other molecules in the cadherin-catenin cell adhesion complex.30,31

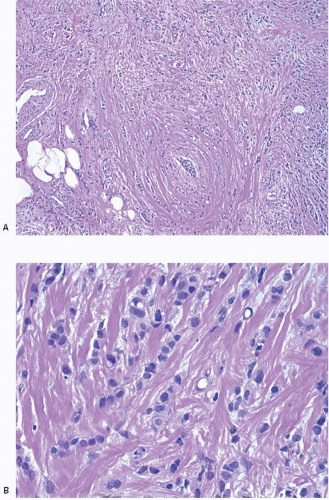

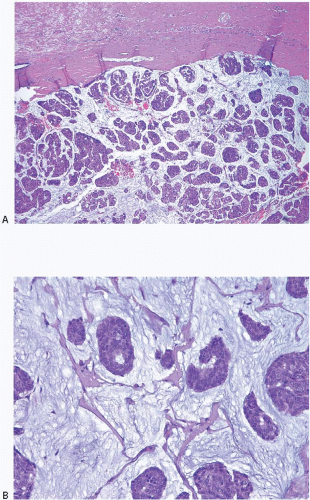

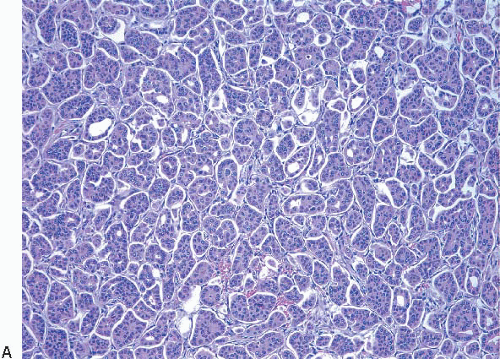

Variant forms of invasive lobular carcinoma differ from the classical form with regard to architectural and/or cytologic features.24,32, 33 and 34 In the solid and alveolar variants, the cells comprising the tumor have features characteristic of the classical form of invasive lobular carcinoma, but differ from the classical form with regard to the growth pattern of the tumor cells. In the solid variant, the neoplastic cells grow in large confluent sheets with little intervening stroma (Fig. 10.6, e-Fig. 10.3). The alveolar variant is characterized by tumor cells that grow in groups of 20 or more cells separated from one another by a delicate fibrovascular stroma (Fig. 10.7). A trabecular variant has also been described, but there is considerable overlap between this pattern and that seen in the classical form of invasive lobular carcinoma. In the pleomorphic variant, the neoplastic cells infiltrate the stroma singly and in linear strands as in classical invasive lobular carcinoma, but are larger, exhibit more nuclear variation than that seen in the classical form, and may show apocrine features (Fig. 10.8, e-Fig. 10.4).35, 36, 37 and 38 Although signet ring cells can be seen in the classical type of invasive lobular carcinoma as well as in some examples of invasive ductal carcinoma, tumors that are composed of a prominent component of signet ring cells that otherwise have the characteristic features of invasive lobular carcinoma are considered to represent the signet ring cell variant of invasive lobular carcinoma.39,40 Histiocytoid carcinoma is a variant of invasive lobular carcinoma in which the tumor cells have a histiocyte-like appearance with abundant foamy, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and mild nuclear atypia (Fig. 10.9).41, 42 and 43 The cells stain for gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP), consistent with apocrine differentiation.

FIGURE 10.6 Invasive lobular carcinoma, solid variant. The cells are similar to those of the classical type, but grow in a solid sheet. |

FIGURE 10.7 Invasive lobular carcinoma, alveolar variant. The tumor cells grow in groups separated by a delicate fibrovascular stroma. |

FIGURE 10.8 Invasive lobular carcinoma, pleomorphic variant. A: Tumor cells infiltrate the stroma singly and in linear strands. B: The cells are larger and show more nuclear pleomorphism than those of classical invasive lobular carcinoma (compare with Fig. 10.3C). Many of the cells have intracytoplasmic vacuoles. |

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Classical invasive lobular carcinomas typically show expression of ER and PR and rarely show HER2 overexpression or gene amplification. Although pleomorphic lobular carcinomas are also frequently ER and PR positive,

they may show HER2 protein overexpression and gene amplification.43 As noted earlier, absence of cell membrane E-cadherin expression is a characteristic and arguably the defining feature of invasive lobular carcinomas, both classical and variant types. The cells of invasive lobular carcinomas also show altered expression of other proteins in the cadherin-catenin complex and, in particular, show cytoplasmic rather than membrane staining for p120 catenin.44 As with LCIS, invasive lobular carcinomas typically show losses on chromosomal arm 16q and gains at 1q. While the majority of invasive lobular carcinomas are classified as luminal A in gene expression profiling studies, some cluster within the luminal B, HER2, and even basal-like groups.14

they may show HER2 protein overexpression and gene amplification.43 As noted earlier, absence of cell membrane E-cadherin expression is a characteristic and arguably the defining feature of invasive lobular carcinomas, both classical and variant types. The cells of invasive lobular carcinomas also show altered expression of other proteins in the cadherin-catenin complex and, in particular, show cytoplasmic rather than membrane staining for p120 catenin.44 As with LCIS, invasive lobular carcinomas typically show losses on chromosomal arm 16q and gains at 1q. While the majority of invasive lobular carcinomas are classified as luminal A in gene expression profiling studies, some cluster within the luminal B, HER2, and even basal-like groups.14

Clinical Course and Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with invasive lobular carcinoma as a group has not consistently been shown to differ from that of patients with invasive ductal carcinoma as a whole. However, the classical type may be associated with a more favorable outcome than variant types and than invasive ductal carcinomas. Available evidence suggests that the pleomorphic variant and the signet ring cell variant (when defined as tumors in which >10% of the neoplastic cells are of the signet ring cell type) appear to be associated with a poor clinical outcome.12,35, 36, 37, 38 and 39

A number of studies have noted differences in the pattern of metastatic spread between invasive lobular and invasive ductal carcinomas.15

In particular, metastases to the lungs, liver, and brain parenchyma appear to be less common in patients with lobular than with ductal cancers. In contrast, lobular carcinomas have a greater propensity to metastasize to the leptomeninges, peritoneal surfaces, and retroperitoneum and to the gastrointestinal tract, reproductive organs, and bone. In fact, the majority of the cases of carcinomatous meningitis in patients with metastatic breast cancer occur in patients with lobular cancers. Peritoneal metastases may appear as numerous small nodules studding the peritoneal surfaces in a manner similar to that seen in ovarian carcinoma. Metastases to the stomach can produce an appearance that simulates an infiltrative (linitis plastica) type of primary gastric carcinoma. Involvement of the uterus may result in vaginal bleeding, whereas a metastatic tumor in the ovary may produce ovarian enlargement and the appearance of a Krukenberg tumor.

In particular, metastases to the lungs, liver, and brain parenchyma appear to be less common in patients with lobular than with ductal cancers. In contrast, lobular carcinomas have a greater propensity to metastasize to the leptomeninges, peritoneal surfaces, and retroperitoneum and to the gastrointestinal tract, reproductive organs, and bone. In fact, the majority of the cases of carcinomatous meningitis in patients with metastatic breast cancer occur in patients with lobular cancers. Peritoneal metastases may appear as numerous small nodules studding the peritoneal surfaces in a manner similar to that seen in ovarian carcinoma. Metastases to the stomach can produce an appearance that simulates an infiltrative (linitis plastica) type of primary gastric carcinoma. Involvement of the uterus may result in vaginal bleeding, whereas a metastatic tumor in the ovary may produce ovarian enlargement and the appearance of a Krukenberg tumor.

Differential Diagnosis

In some classical invasive lobular carcinomas, the cells are widely dispersed in normal-appearing breast stroma, without evidence of a desmoplastic stromal response. As a result, the tumor cells may be entirely overlooked on low-power examination or they may be mistaken for scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells. The solid variant of invasive lobular carcinoma may in some instances be difficult to distinguish from a lymphoma since both may show poorly cohesive sheets of relatively uniform cells. Histologic cues favoring lobular carcinoma are the presence of intracytoplasmic vacuoles and areas in which the cells infiltrate the stroma in the characteristic linear pattern, particularly at the edges of the lesion. In problematic cases, immunostains for cytokeratin, hormone receptors, and lymphoid markers are helpful in arriving at the correct diagnosis. The pleomorphic variant of invasive lobular carcinoma may be difficult to distinguish from a high-grade invasive ductal carcinoma in which the cell nests are compressed and distorted. Stromal invasion in linear strands or as single cells, the presence of intracytoplasmic vacuoles, and absence of cell membrane E-cadherin expression favor a lobular phenotype. The histiocytoid variant may be difficult to distinguish from reactive histiocytic infiltrates, including those associated with fat necrosis. Immunostains for cytokeratin, hormone receptors, and CD68 are valuable adjuncts in making this distinction.

INVASIVE CARCINOMAS WITH DUCTAL AND LOBULAR FEATURES

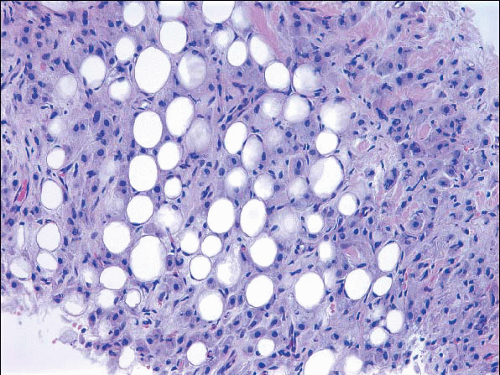

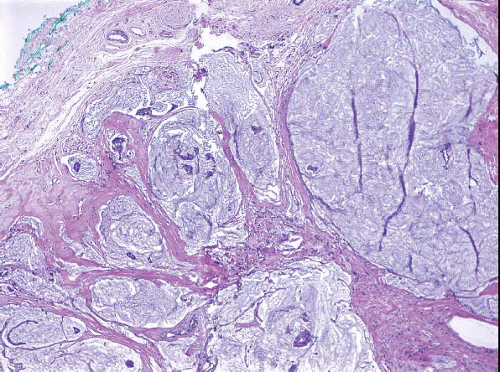

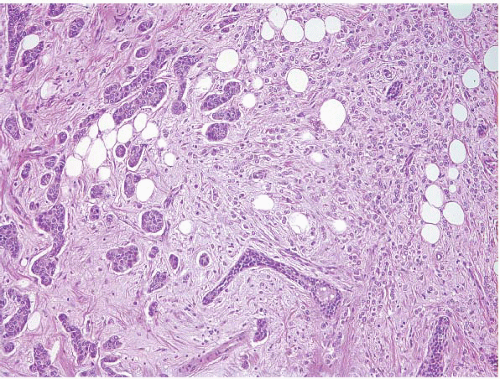

A small proportion of invasive breast cancers (approximately 5%) are not readily classifiable as either ductal or lobular.12 Some such lesions have distinct areas of invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma (Fig. 10.10, e-Fig. 10.5); these are best classified as mixed invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinomas. Others have features that are intermediate between those of invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinomas (Fig. 10.11).

FIGURE 10.10 Mixed invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinoma. Distinct areas of invasive ductal carcinoma (left) and invasive lobular carcinoma (right) are evident. |

FIGURE 10.12 Tubulolobular carcinoma. The tumor consists of both linear strands of neoplastic cells and round glandular structures. |

Tubulolobular carcinoma is a distinctive type of invasive breast cancer with both ductal and lobular features. In these lesions, some of the tumor cells invade the stroma in the linear strands characteristic of the classical form of invasive lobular carcinoma, whereas others form small tubules. The tubules tend to have rounded to ovoid contours and are smaller and less angulated than those seen in tubular carcinoma (Fig. 10.12, e-Fig. 10.6). Although tubulolobular carcinomas have traditionally been considered to be variants of invasive lobular carcinoma, recent studies have indicated that the cells comprising these lesions consistently show membranous expression of E-cadherin, suggesting that tubulolobular carcinomas are variants of invasive ductal rather than lobular carcinoma.45 However, given that some invasive lobular carcinomas exhibit E-cadherin staining,30,31 the presence of E-cadherin expression in tubulolobular carcinomas is in our view insufficient proof that these lesions are variants of ductal rather than lobular carcinoma.

TUBULAR CARCINOMA

Tubular carcinoma is a special type cancer that is associated with limited metastatic potential and an excellent prognosis. Prior to the widespread use of screening mammography, tubular carcinomas accounted for <4% of all breast cancers.46 However, these tumors account for a much higher proportion of cancers detected in mammographically screened populations, with incidence rates ranging from 7.7% to 27%.47,48

Clinical Presentation

Historically, tubular carcinomas were detected as palpable lesions. However, the majority (60% to 70%) now present as nonpalpable mammographic abnormalities. Not infrequently, tubular carcinomas are discovered incidentally in biopsies performed for unrelated reasons.

When a mammographic abnormality is present, it is usually a mass lesion and is only occasionally associated with microcalcifications. The majority of tubular carcinomas have spiculated margins and cannot be distinguished radiologically from invasive ductal carcinomas.

Gross Pathology

Grossly, tubular carcinomas are firm, spiculated lesions that are indistinguishable from invasive ductal carcinomas.

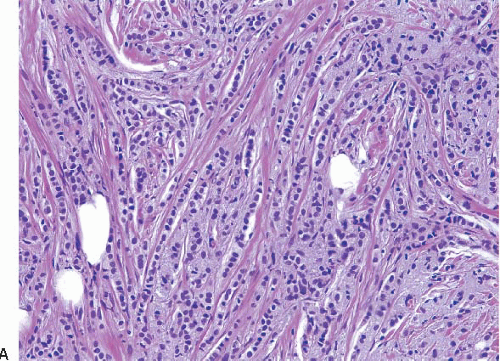

Histopathology

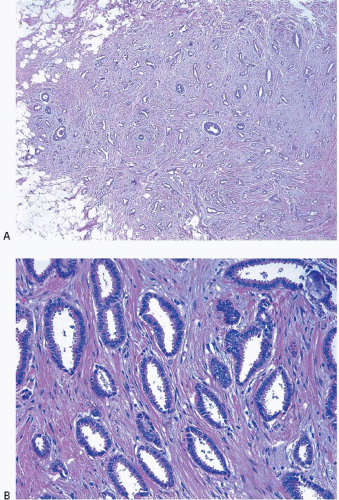

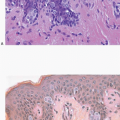

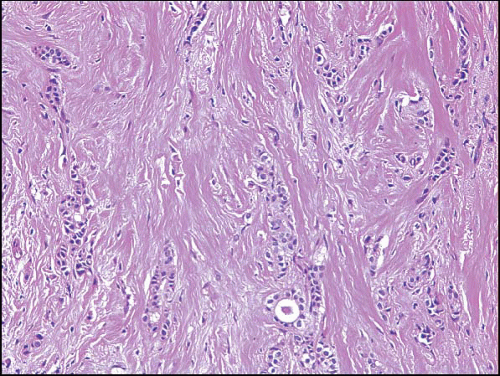

Tubular carcinomas are characterized by a haphazard proliferation of well-formed glands or tubules composed of a single layer of epithelial cells without a surrounding myoepithelial cell layer. These tubules tend to be ovoid in shape and have sharply angular contours with tapering ends and open lumens. The cells comprising these tubules are characterized by lowgrade nuclei and often exhibit apical cytoplasmic “snouts.” The stroma of tubular carcinomas usually has desmoplastic features, and prominent elastosis may be present in some cases (Fig. 10.13, e-Fig. 10.7).49 There is now general agreement that >90% of the tumor should exhibit this characteristic morphology to be categorized as a “pure” tubular carcinoma; tumors with <90% tubular elements are referred to by some as “mixed” tubular carcinomas.46

The majority of tubular carcinomas have an associated component of DCIS. This is usually of low nuclear grade with cribriform and micropapillary patterns. In addition, flat epithelial atypia is often found in association with tubular carcinomas (see Chapter 4). LCIS and atypical lobular hyperplasia may also be observed.

Some studies have suggested that the frequency of multifocality and multicentricity in tubular carcinoma is higher than in invasive ductal carcinomas.

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Patients with tubular carcinoma have an excellent prognosis.51,52 In fact, in some series, the prognosis is similar to that of age-matched women

without breast cancer.52 Axillary lymph node metastases have been reported in up to 15% of patients with these tumors and this is related to the tumor size (e-Fig. 10.7C).53 When tubular carcinoma does metastasize to axillary lymph nodes, usually one and seldom more than three nodes are involved. Several studies have concluded that even the presence of nodal disease in patients with tubular carcinoma does not affect disease-free or overall survival.50,53

without breast cancer.52 Axillary lymph node metastases have been reported in up to 15% of patients with these tumors and this is related to the tumor size (e-Fig. 10.7C).53 When tubular carcinoma does metastasize to axillary lymph nodes, usually one and seldom more than three nodes are involved. Several studies have concluded that even the presence of nodal disease in patients with tubular carcinoma does not affect disease-free or overall survival.50,53

Differential Diagnosis

Because these lesions are composed of well-formed glands, several benign lesions must be considered in the differential diagnosis including sclerosing adenosis, radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions, microglandular adenosis, and tubular adenosis. In some cases, the distinction of tubular carcinoma from these other lesions may be difficult on histologic grounds alone and adjunctive immunostains may be necessary in order to arrive at the correct diagnosis. In particular, stains for myoepithelial cells are of value in distinguishing tubular carcinoma from benign sclerosing lesions (i.e., sclerosing adenosis and radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions) and from tubular adenosis. Myoepithelial cell stains are not helpful in distinguishing tubular carcinoma from microglandular adenosis since the glands in both of these lesions lack an outer myoepithelial cell layer. However, immunostains for S-100 protein and ER are helpful in this distinction (see Chapter 7).

Tubular carcinomas must also be distinguished from grade 1 invasive ductal carcinomas of NST. In general, the glands of grade 1 invasive ductal carcinomas do not have the ovoid shape, pointed ends, and apical cytoplasmic snouts that characterize the glands of tubular carcinoma. This distinction is important since the prognosis of tubular carcinomas is better than that of grade 1 invasive ductal carcinomas.51,52

INVASIVE CRIBRIFORM CARCINOMA

Invasive cribriform carcinoma is a well-differentiated cancer associated with a favorable prognosis. It is uncommon, accounting for approximately 1% to 3.5% of invasive breast cancers.46,54,55

Clinical Presentation

The tumor may present as a palpable mass, but is often clinically occult and detected by mammography as a spiculated mass with or without microcalcifications.

Gross Pathology

No distinctive gross features of invasive cribriform carcinoma have been described.

Histopathology

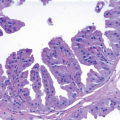

Invasive cribriform carcinomas are characterized by small tumor cells with little nuclear pleomorphism that invade the stroma as cribriform or fenestrated cellular islands that resemble cribriform pattern DCIS.

The contour of these islands varies from smooth to angulated (Fig. 10.14, e-Fig. 10.8). These tumors often show admixtures of other histologic patterns of invasive breast cancer, particularly tubular carcinoma, which is seen in approximately 20% of the cases. In about 80% of the cases, there is an associated component of DCIS, usually with a cribriform pattern.

The contour of these islands varies from smooth to angulated (Fig. 10.14, e-Fig. 10.8). These tumors often show admixtures of other histologic patterns of invasive breast cancer, particularly tubular carcinoma, which is seen in approximately 20% of the cases. In about 80% of the cases, there is an associated component of DCIS, usually with a cribriform pattern.

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Approximately 14% of patients have axillary lymph node metastases. As mentioned previously, invasive cribriform carcinoma has an excellent prognosis, with 10-year survival rates of >90% being reported. The prognosis of patients with pure invasive cribriform carcinomas is better than that of patients in whom the cribriform component is mixed with other histologic types.46,54,55

Differential Diagnosis

The major differential diagnostic consideration for invasive cribriform carcinoma is cribriform pattern DCIS. Further, in some lesions characterized by a cribriform pattern, it may be difficult to determine the relative proportions of invasive cribriform carcinoma and cribriform DCIS. Invasive cribriform carcinoma has a haphazard distribution and infiltrates between ducts and lobules, whereas DCIS maintains the normal ductal and lobular architecture. In contrast to cribriform DCIS where the involved spaces have smooth, rounded contours, at least some of the infiltrating islands of invasive cribriform carcinoma have irregular, sharp, and angulated borders. The stroma in invasive cribriform carcinoma tends to be desmoplastic, whereas there is a lack of associated stromal change in most cribriform DCIS. Lastly, the nests of invasive cribriform carcinomas lack myoepithelial cells surrounding the glandular islands, whereas a peripheral myoepithelial cell layer is present in cribriform pattern DCIS. If these cells cannot be appreciated on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, immunostains for myoepithelial cell markers may be used to aid in this distinction; this approach may also be used to help define the relative proportions of invasive carcinoma and DCIS.

Invasive cribriform carcinomas must also be distinguished from adenoid cystic carcinomas, which are commonly characterized by cribriform tumor cell nests. The presence in adenoid cystic carcinomas of a dual epithelial/myoepithelial cell population and intraluminal mucoid and/or basement membrane material are useful clues to the correct diagnosis because these features are not seen in invasive cribriform carcinoma. Furthermore, adenoid cystic carcinomas are typically ER negative, whereas invasive cribriform carcinomas are virtually always ER positive.

MUCINOUS CARCINOMA

Mucinous carcinoma (also known as colloid carcinoma) is another special type cancer that is associated with a relatively favorable prognosis. These tumors are uncommon and in most series account for approximately 2% of invasive breast carcinomas.56

Clinical Presentation

Mucinous carcinomas occur over a wide age range. In a recent review of over 11,000 mucinous carcinomas from the SEER database, the median age was 71 years (range 25 to 85 years)57; this median age is higher than that of patients with invasive ductal carcinomas of NST. Patients with mucinous carcinoma may present with palpable tumors. However, since the introduction of widespread screening mammography, a substantial proportion of patients with mucinous carcinoma (30% to 70%) present with nonpalpable mammographic lesions.58,59 Mammographically, mucinous carcinomas are most often circumscribed or lobulated masses that are rarely associated with calcification.

Gross Pathology

Mucinous carcinomas typically have a circumscribed or bosselated contour, a variably soft, gelatinous consistency, and a glistening cut surface.

Histopathology

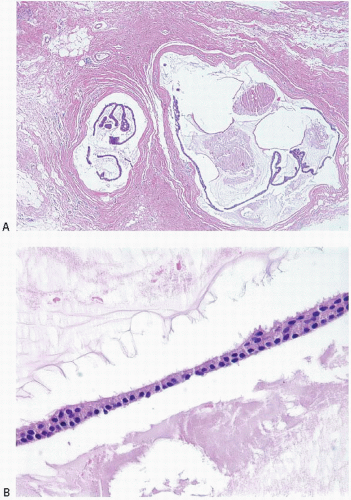

The hallmark of mucinous carcinomas is extracellular mucin production. However, the extent of extracellular mucin varies from tumor to tumor. Typically, tumor cells in small clusters are dispersed within pools of extracellular mucin, which may be traversed by thin fibrous septae containing thin-walled blood vessels. On occasion, the cells assume a glandular, trabecular, sheet-like, papillary, or micropapillary configuration. The nuclei are generally of low or intermediate grade; rarely, high-grade nuclear features are present. This characteristic histology should comprise at least 90% of the tumor (or 100% according to some) to qualify for the diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma.56 Mucinous carcinomas with foci of carcinoma that have nonmucinous features are classified as “mixed” mucinous tumors. The cellularity of mucinous carcinomas is variable, with some tumors being highly cellular (type B mucinous carcinomas) and others paucicellular (type A mucinous carcinomas) (Figs. 10.15 and 10.16, e-Fig. 10.9).60 The type B carcinomas frequently exhibit endocrine differentiation as defined by either cytoplasmic argyrophilic granules or immunoreactivity for the endocrine markers chromogranin or synaptophysin.60, 61 and 62 Mucinous carcinomas are often accompanied by a DCIS component, which may have a micropapillary, papillary, cribriform, or solid pattern. Rarely comedo necrosis is present. The DCIS may also exhibit prominent extracellular mucin production.

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Mucinous carcinomas are typically ER positive and about 70% are PR positive. In addition, mucinous carcinomas usually do not overexpress the HER2 protein or show HER2 gene amplification.50 These tumors are characterized by relatively few chromosomal losses and gains and show relatively little genomic instability.63 Mucinous carcinomas cluster within the luminal A molecular subtype in gene expression profiling studies.14 However, expression signatures of type A mucinous carcinomas are distinct from those of type B lesions, the latter having an expression profile similar to that of carcinomas with endocrine features.64

Clinical Course and Prognosis

In the SEER database review of over 11,000 patients with mucinous carcinoma noted above, 12% of patients had axillary nodal metastases at presentation.57 The frequency of nodal involvement is related to tumor size; axillary lymph node involvement is exceptionally rare in mucinous carcinomas <1 cm in size.50 Patients with pure mucinous carcinoma generally have a favorable prognosis. In the large SEER review,57 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year survival rates were 94%, 89%, 85%, and 81%, respectively, for patients with mucinous carcinoma compared with 82%, 72%, 66%, and 62%, respectively, for patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type. Late systemic recurrences (>25 years after diagnosis) may

be seen.50,57 Nodal involvement is the most important adverse prognostic factor in these patients.57 The prognostic importance of endocrine differentiation in mucinous carcinomas is not sufficiently established to be considered a standard prognostic feature.

be seen.50,57 Nodal involvement is the most important adverse prognostic factor in these patients.57 The prognostic importance of endocrine differentiation in mucinous carcinomas is not sufficiently established to be considered a standard prognostic feature.

Differential Diagnosis

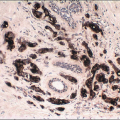

The differential diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma includes other mucinproducing lesions of the breast, particularly mucocele-like lesions. Mucocele-like lesions are characterized by cystically dilated, mucin-filled ducts, often associated with rupture and extravasation of mucin into the stroma. The epithelium lining the ducts may be attenuated or show a spectrum of proliferative changes ranging from hyperplasia to atypical ductal hyperplasia to DCIS (Figs. 10.17 and 10.18).68, 69 and 70 In some cases, strips or clusters of epithelium may become detached from the duct walls and lie free within mucin pools; the distinction from mucinous carcinoma may be difficult in such cases, particularly if the epithelial strips or clusters are derived from DCIS (Fig. 10.19, e-Fig. 10.10). Features favoring a mucocele-like lesion with epithelial detachment are a linear configuration of the epithelium (resembling a duct lining) and the presence of associated myoepithelial cells; the latter may require immunostains for their demonstration. However, in some cases, particularly those associated with DCIS, it may not be possible to definitively distinguish a mucocelelike lesion with detached epithelium from mucinous carcinoma. In addition, the distinction between mucinous carcinoma and mucocele-like lesion may be difficult or impossible on core-needle biopsy. Given that some mucinous carcinomas feature abundant mucin with few neoplastic cell clusters, it is not possible to exclude a mucinous carcinoma in coreneedle biopsy samples that contain stromal mucin pools, even if they are devoid of neoplastic cell nests. Excision should be recommended in such cases for definitive evaluation.

FIGURE 10.17 Mucocele-like lesion. This lesion is composed of variably dilated mucinfilled ducts with foci of stromal mucin extravasation. The epithelium lining the ducts is attenuated. |

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma is another mucin-producing lesion of the breast that must be distinguished from mucinous carcinomas (see the subsequent text).71 Several other lesions may also enter into the differential diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma including fibroadenoma with prominent myxoid stroma, myxoma, neurofibroma with prominent myxoid change, and matrix-producing metaplastic carcinoma.

MEDULLARY CARCINOMA AND CARCINOMAS WITH MEDULLARY FEATURES

Medullary carcinomas are rare and in our experience account for <1% of all invasive breast cancers. The pathologic diagnosis of this tumor is subject to considerable interobserver variability.72,73 Lesions with some but not all of the features of medullary carcinoma have been variously termed

“atypical medullary carcinomas,” “invasive carcinomas with medullary features,” and “invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features.” In view of the difficulties in reproducibly applying the diagnostic criteria for medullary carcinoma, the 2011 WHO Working Group recommended that medullary carcinomas, atypical medullary carcinomas, and invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features be grouped together as “carcinomas with medullary features.”74

“atypical medullary carcinomas,” “invasive carcinomas with medullary features,” and “invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features.” In view of the difficulties in reproducibly applying the diagnostic criteria for medullary carcinoma, the 2011 WHO Working Group recommended that medullary carcinomas, atypical medullary carcinomas, and invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features be grouped together as “carcinomas with medullary features.”74

Clinical Presentation

Tumors in this group usually present at a younger age than patients with other breast cancers. This is at least partially explained by the fact that some patients with these tumor harbor BRCA1 germline mutations (see the Pathologic Features of Hereditary Breast Cancer section). The majority of patients present with a palpable mass. Although some patients exhibit axillary lymphadenopathy at the time of presentation, histologic examination of the lymph nodes in such cases typically reveals benign reactive changes rather than metastatic carcinoma.

In mammographic studies, most medullary carcinomas appear as a fairly well-defined mass unassociated with calcifications.75 However, a significant proportion of the cases of medullary carcinoma are associated with an ill-defined margin. Moreover, the majority of mammographically well-circumscribed cancers are invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type rather than medullary carcinomas.76

Gross Pathology

Upon gross examination, medullary carcinomas are well-circumscribed, soft, tan-brown to gray tumors that bulge above the cut surface of the specimen. A multinodular appearance may be appreciated in some cases. Areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystic degeneration may be present.

Histopathology

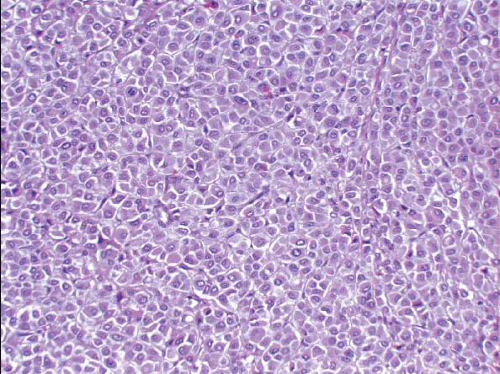

Several similar but distinct classification systems for the histologic diagnosis of medullary carcinomas have been proposed.77, 78, 79 and 80 All of these classification schemes recognize the following attributes of medullary carcinomas, but the relative importance and the mandatory nature of each are stressed to a different degree: (a) syncytial growth pattern of the tumor cells in more than 75% of the tumor, (b) admixed lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, (c) microscopic circumscription, (d) grade 2 or 3 nuclei, and (e) absence of glandular differentiation (Fig. 10.20, e-Fig. 10.11). Tumors that lack a variable number of these characteristics (depending on the system used) have been classified in these systems as “atypical medullary carcinoma” or invasive ductal carcinoma.

Medullary carcinomas may show foci of hemorrhage, necrosis, cystic degeneration, and various types of metaplasia of the tumor cells, most often squamous metaplasia. In some tumors, the neoplastic cells may exhibit bizarre cytologic features with marked nuclear atypia and multinucleated giant cell forms. There is usually little or no associated DCIS.

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Carcinomas in this group are typically negative for ER and PR and lack HER2 protein overexpression and gene amplification (“triple negative”).

They variably express basal cytokeratins (CK5/6, 14, and 17) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). These tumors show considerable genomic instability. Most breast cancers in women with germline BRCA1 mutations have medullary features, and many sporadic carcinomas with these features exhibit somatic inactivation of this gene by one of several different molecular mechanisms. Mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene are especially common. Medullary carcinomas and carcinomas with medullary features typically cluster within the basal-like group in gene expression profiling studies.14

They variably express basal cytokeratins (CK5/6, 14, and 17) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). These tumors show considerable genomic instability. Most breast cancers in women with germline BRCA1 mutations have medullary features, and many sporadic carcinomas with these features exhibit somatic inactivation of this gene by one of several different molecular mechanisms. Mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene are especially common. Medullary carcinomas and carcinomas with medullary features typically cluster within the basal-like group in gene expression profiling studies.14

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Although studies have differed in the histologic criteria employed, most indicate that the incidence of axillary lymph node metastases is lower in patients with medullary carcinomas than in those with atypical medullary carcinomas or invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features.

Outcome data for patients with medullary carcinoma are confounded by the use of differing classification systems and interobserver variability. These tumors have traditionally been thought of as having a more favorable prognosis than invasive ductal carcinomas of NST; however, a more favorable prognosis has not been observed in all studies. Most deaths occur within 5 years after diagnosis. Data from one large clinical cohort with long-term follow-up suggested that the prognosis of these tumors is similar to that of grade 3 invasive ductal carcinomas with a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, but better than that of grade 3 invasive ductal carcinomas without a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate.81

Differential Diagnosis

The absence of nesting of the large neoplastic cells, the minimal stroma, and the admixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells may create an appearance that raises the question of lymphoma. In such cases, immunostains for cytokeratin are of value in defining the epithelial nature of the malignant cells. In addition, the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and circumscription of these tumors may create difficulty in distinguishing a medullary carcinoma from a metastasis in an intramammary lymph node. However, medullary carcinomas lack the capsule and other underlying architectural features of lymph nodes.

Given the poor interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of medullary carcinoma and the overlap of medullary carcinomas, atypical medullary carcinomas, and invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features with regard to their histologic features, biomarker expression, genomic alterations, and molecular subtype, there is a growing trend away from separating these tumors from each other. As noted above, the 2011 WHO Working Group recommended that these tumors be grouped together within a single category of “carcinomas with medullary features,” thereby eliminating the need to distinguish among them.74

INVASIVE MICROPAPILLARY CARCINOMA

Invasive micropapillary carcinoma accounts for <2% of invasive breast carcinomas in pure form. It is more common to see foci of invasive micropapillary carcinoma admixed with other histologic types, particularly invasive ductal carcinomas of NST. Patients with this tumor type

commonly have axillary lymph node metastases at presentation and have a relatively poor prognosis.82, 83, 84, 85, 86 and 87

commonly have axillary lymph node metastases at presentation and have a relatively poor prognosis.82, 83, 84, 85, 86 and 87

Clinical Presentation

Patients may present with a palpable mass or with a mammographically detected lesion without features that permit their distinction from other types of breast cancers.

Gross Pathology

No distinguishing gross features have been described. The median size reported for invasive micropapillary carcinoma is significantly larger than invasive ductal carcinomas of NST.

Histopathology

These lesions are characterized by clusters of cells in a micropapillary or tubular-alveolar arrangement, which appear to be suspended in clear spaces. These micropapillary clusters, unlike true papillary lesions, lack fibrovascular cores. The cells in these clusters have an “inside-out” arrangement, with the apical surface polarized to the outside, toward the stroma (Fig. 10.21). This feature can be highlighted using an immunostain for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (Fig. 10.22). The overall appearance of invasive micropapillary carcinoma may mimic serous papillary carcinomas of the ovary or may simulate LVI. True LVI has been reported in 33% to 67% of cases and may be extensive. It may be difficult to determine if particular nests of tumor cells in clear spaces represent foci of invasive micropapillary carcinoma or LVI. Cytologically, the cells comprising the invasive micropapillary carcinoma usually have low- to intermediate-grade nuclei. The majority of tumors (˜70%) are associated with a DCIS component with micropapillary and cribriform patterns.

Invasive micropapillary carcinomas may occur in pure form or may be admixed with invasive ductal carcinoma of NST or, in a minority of cases, with mucinous carcinoma (e-Fig. 10.12).86 It is not clear if tumors with both invasive micropapillary and mucinous components should be classified as mixed lesions or as mucinous variants of invasive micropapillary carcinoma.

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

The majority of invasive micropapillary carcinomas are ER positive (˜60% to 100%) and almost half are PR positive. HER2 protein overexpression has been observed in up to one-third of reported cases.88 Most invasive micropapillary carcinomas are classified as luminal A or luminal B subtypes in gene expression profiling studies.14

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Up to 75% of patients with invasive micropapillary carcinomas have axillary lymph node metastases at the time of initial presentation.82, 83, 84, 85, 86 and 87 The frequency of lymph node involvement is similar for pure invasive micropapillary carcinomas and for those lesions in which an invasive micropapillary pattern constitutes only a minor component of a breast cancer. Therefore, it is important that the pathologist recognize and report an invasive micropapillary component in an invasive breast cancer, even if present as a minor component.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree